No fanfare or celebrations as Irish Free State is born

Dublin, 7 December 1922 – A year after the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in London, the Irish Free State has officially come into existence.

The provisional government is no more and when TDs reconvened on 6 December, they did so to choose a cabinet which will be known as the executive council and to elect members to the first ever Seanad. Once the Seanad meets for the first time, the Oireachtas will be officially constituted.

The first formal sitting of the Saorstát parliament was notable for its lack of pomp and ceremony and the occasion attracted only a small crowd outside of Leinster House, where a magnificent new tricolour flag, specially made, flew in the breeze.

An order recently introduced prohibiting admission to the public galleries, ensured a low-key atmosphere. And while opponents of the treaty were understandably absent, a large number of reporters representing newspapers in Ireland, England, Continental Europe and the United States, were in attendance.

Once the proceedings began, the ministers in the new Free State Government took the controversial oath of allegiance. The Speaker, Michael Hayes, then proceeded to administer the oath to the remaining deputies, one of whom, the Labour leader Thomas Johnson, placed on record their reluctant acceptance of the oath as a ‘formality, a condition of membership of the legislature, implying no obligation other than the ordinary obligation of every person who accepts the privileges of citizenship.’

Mr Johnson continued that while the Labour TDs were taking the oath to fulfil their pledge, they do so in the knowledge that the terms of the treaty had been accepted by the Irish people only under protest, ‘having been imposed upon Ireland by the threat of superior force, and were not freely determined by the people of Ireland or their representatives.’

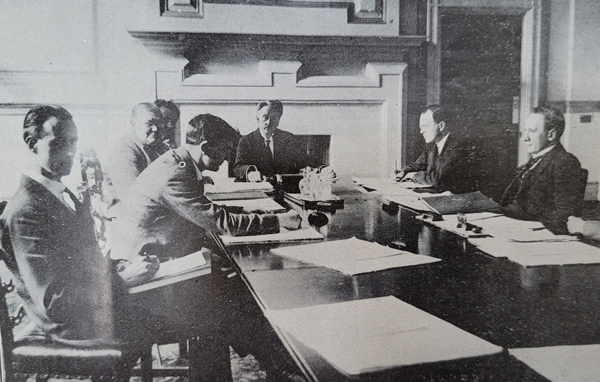

British Pathé footage of the establishment of the Free State in 1922

The centrepiece of the first sitting of the Free State parliament was the presidential address of William T. Cosgrave, head of the new executive council. He described it as a ‘notable day when our country has definitely emerged from the bondage under which she has lived through a week of centuries.’

President Cosgrave spoke of his pride to lead ‘the first government which takes over the control of the destiny of our people, to hold and administer that charge, answerable only to our own people and to none other; to conduct their affairs as they shall declare right without interference, not to say domination, by any other authority whatsoever on this earth.’

He devoted much of his speech to the future relationship between the Free State and Northern Ireland.

While his government was bound to adhere to the terms of treaty, President Cosgrave, remarked that they were ‘looking northwards with hope and confidence that, whether now or very soon the people of that corner of our land will come in with the rest of the Irish Nation, and share with us its Government as well as the great prosperity and happiness which must certainly follow concord and union. Let them, we beg them, weigh well the substantial guarantees assured to them in the event of their deciding to recognise the Treaty position, as it regards them.’

President Cosgrave outlined the advantages of joining with the Free State and the protections they would enjoy.

If the government of Northern Ireland decides against joining the Free State President Cosgrave highlighted the Free State’s ‘solemn pledges’ to nationalists in the six counties who were ‘crying out daily to be included in the Irish Free State’.

If unionist Ulster couldn’t be forced into a Free State, then it couldn’t coerce those areas within the six counties who wished to join – as evidenced most recently in the election in Fermanagh/Tyrone. Referring to the Boundary Commission, the president noted the British government’s pledge that the wishes of the inhabitants of the various parts of the six counties will be respected. That was part and parcel of the treaty.

Concluding his address, President Cosgrave said:

‘In so far as my government and myself are concerned we shall say nothing, nor do anything, that may in any way hold apart from us that part of the province of Ulster now separated or retard the advent of that union which alone can bring real harmony, and lasting and genuine security to our Common Motherland.’

[Editor's note: This is an article from Century Ireland, a fortnightly online newspaper, written from the perspective of a journalist 100 years ago, based on news reports of the time.]