Anglo-Irish treaty signed in London

London, 7 December 1921 – Nearly five months after a truce brought an end to the Anglo-Irish war, and three months since the commencement of peace talks, negotiators representing the British government and Dáil Éireann have reached a historic agreement.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed at 2.15am yesterday, and 15 minutes later the Exchange Telegraph Company sent the following message: ‘An agreement has been reached.’

The terms of the treaty will now be recommended for acceptance to the Westminster Parliament and to Dáil Éireann. A copy of the agreement has also been sent to Sir James Craig by special messenger.

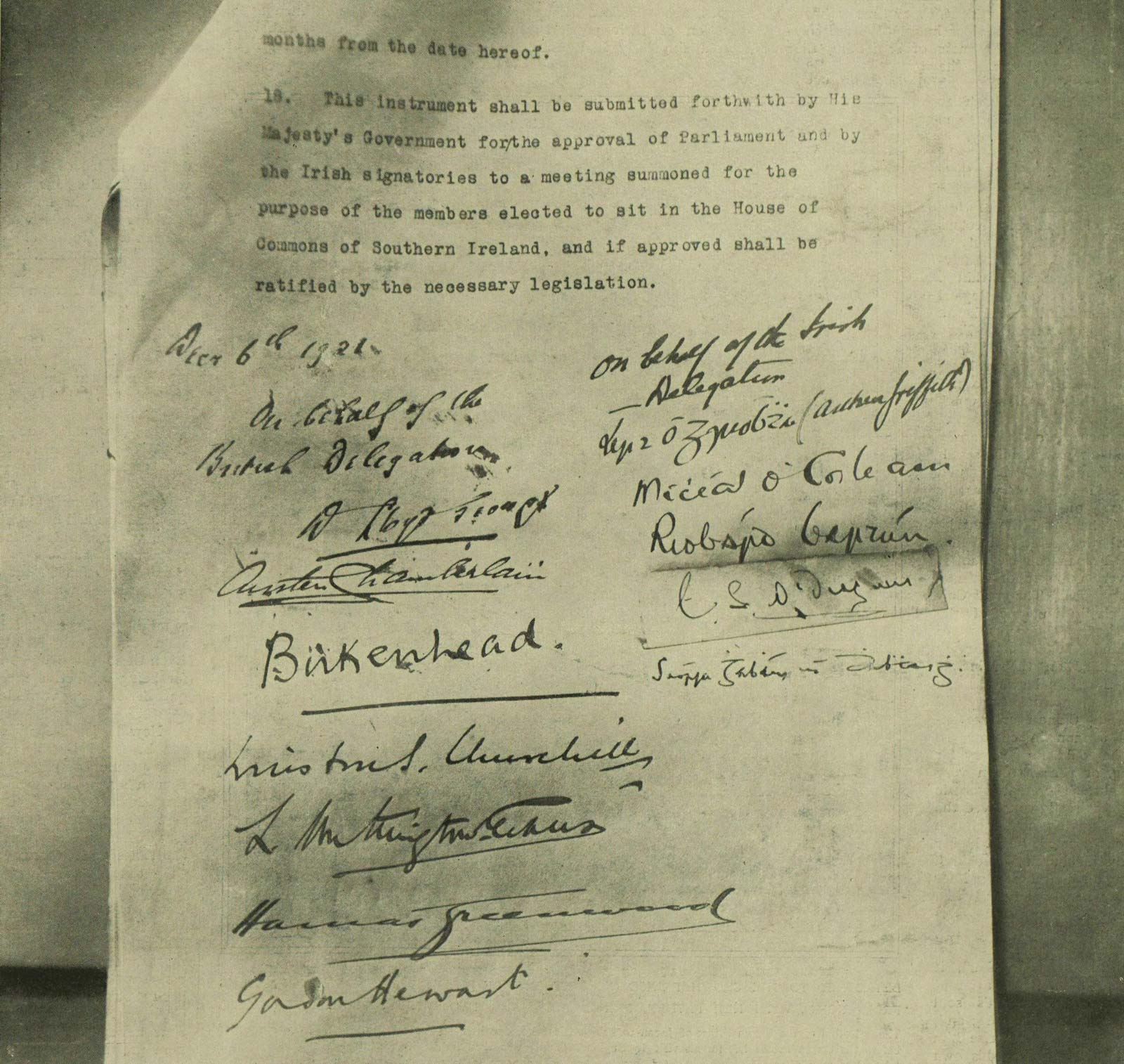

When asked if he had anything to say when leaving Downing Street at 2.20am, Michael Collins, who was accompanied by Arthur Griffith and Robert Barton, replied: ‘Not a word.’

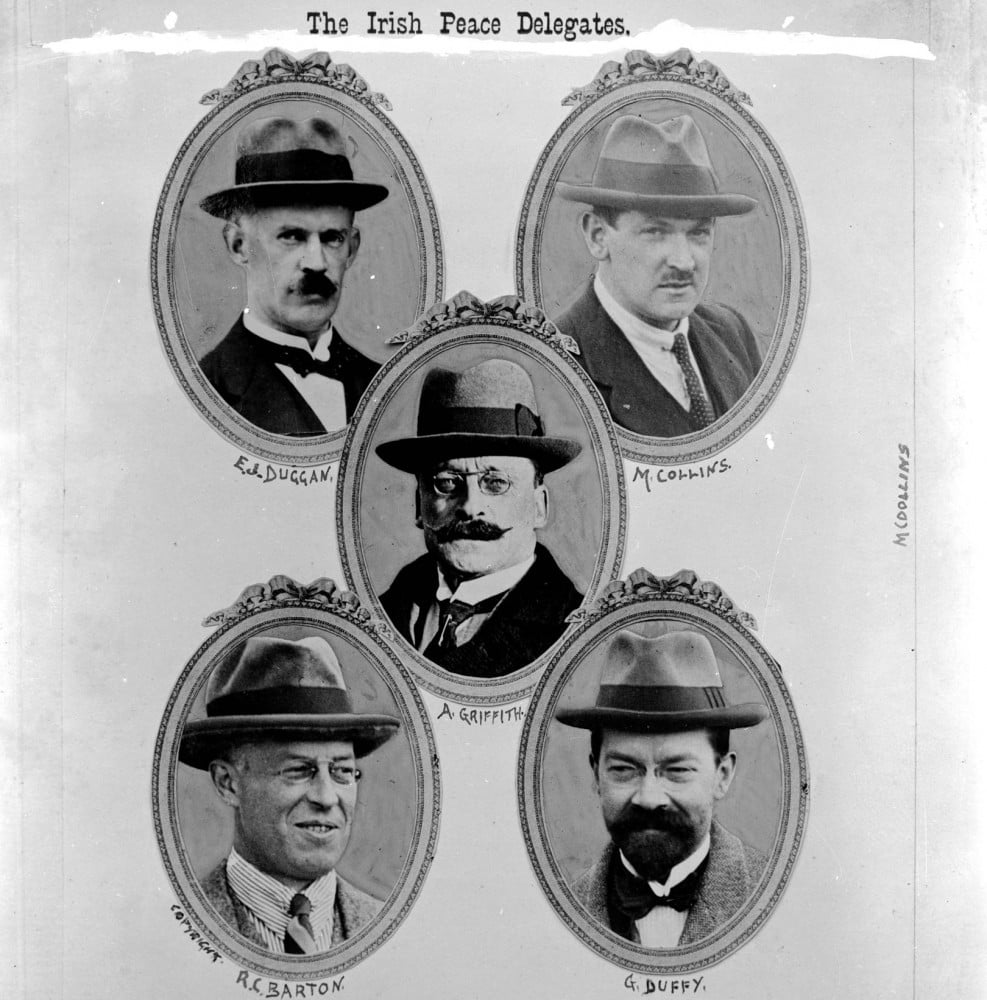

The Irish signatories of the Treaty (Image: RTÉ Archives 0508/049)

The agreement came at the end of a day of feverish activity which saw the British Prime Minister visit King George V, and saw the Irish plenipotentiaries visit Downing Street twice.

After the Irish delegates left Downing Street following an afternoon discussion, an official statement issued by the British government stated that ‘proposals with certain alterations and modifications had been given to the three delegates, who had gone to consult with their colleagues at the Irish delegation headquarters.’

Griffith, Collins and Barton, accompanied by Erskine Childers, returned to Downing Street at 11.15pm.

Difficulties during the day

At many times during the day, it appeared that a deal was

impossible. Briefing journalists as the British Cabinet met

yesterday morning, Geoffrey Shakespeare, one of the British Prime

Minister’s private secretaries, remarked that the situation

was ‘most critical’ and he could not confirm that the

outstanding obstacles would be overcome. ‘Sinn

Féin,’ he said, ‘absolutely refuses to come

within the empire and acknowledge the crown. I don’t see,

personally, what can be done.’

The Irish Independent has highlighted the ‘impropriety’ of Mr Shakespeare’s remarks and said that the moment called for ‘broadminded, wise, honest and courageous’ statesmanship.

‘The issues at stake are in themselves and in the consequences which they involve, the most momentous that have ever arisen in the history of the relations between the two islands.’

Terms of the treaty

According to the text of the treaty, Ireland is to be afforded

dominion status with a parliament of its own but will remain

within the British empire similar to Australia, Canada, New

Zealand and South Africa. It will be known as the Irish Free State

and the crown will be represented by a Governor-General, similar

to the system in Canada.

Furthermore, the agreement provides for an oath of allegiance to be taken by the members of the new Irish Free State Parliament. It reads:

‘I do solemnly swear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of the Irish Free State as by law established and that I will be faithful to H.M. King George V, his heirs and successors by law, in virtue of the common citizenship of Ireland with Great Britain and her adherence to and membership of the group of nations forming the British Commonwealth of Nations.’

The Treaty allows for the territory of Northern Ireland, established under the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, to remain outside of the Free State and should Northern Ireland exercise that option, a Boundary Commission is to be established to determine the borders between north and south.

The National Archives of Ireland’s exhibition on the Anglo-Irish Treaty is running from 6 December 2021 until the end of March 2022

[Editor's note: This is an article from Century Ireland, a fortnightly online newspaper, written from the perspective of a journalist 100 years ago, based on news reports of the time.]