8 December 1922: The Mountjoy Executions

Abandoning The Rule of Law: State Executions During the Irish Revolution

by Seán Enright

The execution without trial of Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Richard Barrett and Joe McKelvey on 8 December 1922 at Mountjoy Prison was one of the most notorious events of the Irish civil war. It should be understood within the context of the Irish Free State government’s execution policy, and also as part of the wider resort to executions by British governments throughout the revolutionary period.

By the autumn of 1922 the financial cost of the civil war was

edging the country towards bankruptcy. At the request of the

Provisional Government, the National Army issued a proclamation

that, after 15 October, persons ‘taken in arms’ or

‘attacking National Army troops’ would be tried by

military court and ‘suffer death’. The first

executions soon followed, and a legal challenge to the military

courts failed.¹

Liam Lynch wrote to the Speaker of the Dáil demanding that

the executions cease or there would be immediate reprisals. His

warning was ignored and three more anti-Treaty fighters were

executed. On 7 December, the day after the Irish Free State came

into existence, Seán Hales TD was shot dead as part of the

anti-Treaty reprisal policy.

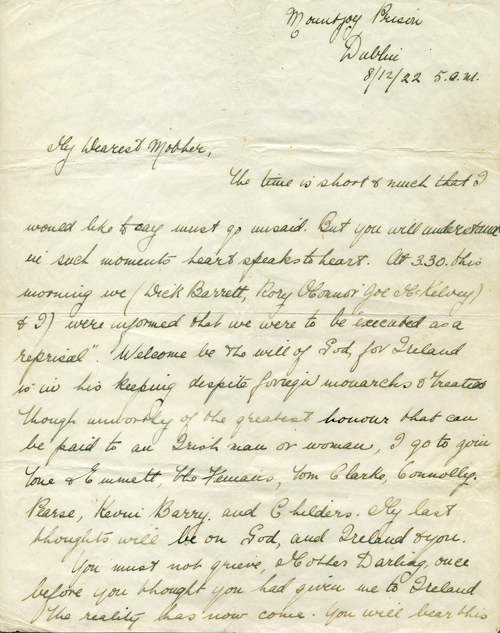

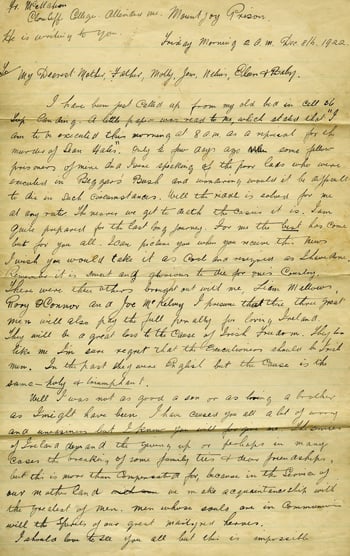

That same evening the Cabinet of the new state met and fixed upon reprisal executions of four untried prisoners. The men at Mountjoy Prison were woken and handed a typed sheet: ‘being a person taken in arms against the government, you will be executed at 8am in reprisal for the assassination of Brigadier Seán Hales.’² They were shot at Mountjoy that morning. After the volley from the firing squad nine more bullets were needed from the supervising officers. The last to die was Joe McKelvey. ‘Give me another’, he asked. Another bullet was fired. ‘And another.’³

There was no point in a trial, one minister observed sagely: the role the men had played in the Four Courts siege was well known .⁴ In the Dáil debate that afternoon there were many who insisted that due process should not have been abandoned. It was pointed out that the prisoners had been in custody for months, bore no responsibility for the anti-Treaty reprisal policy, and such offences as they might have committed took place before the army proclamation created capital offences. The execution of these men represented the nadir of due process during the war. The many other executions that took place during the civil war were preceded by trial by military court. But what did that actually mean?

The military court phenomenon pervaded the Irish revolution from

the outset. The principle of law, as it was then, was that the

army had no jurisdiction to try civilians or anyone other than its

own soldiery. In Britain this principle had subsisted for

centuries and it had been maintained in colonies, save where

rebellion required the military to bring in martial law to restore

the status quo by trial and execution. Necessity was the guiding

principle and senior army officers knew that what they did was

justiciable after the conflict was over. Despite this, the

suppression of rebellions in Ireland and the colonies was marked

by extraordinary excesses. This history began to shape policy in

Westminster and, when the Great War broke out, the Defence of the

Realm Act was passed permitting trial by court martial in Ireland

for capital offences in the event of ‘invasion or other

special military emergency’.⁵

This was not martial law: it was an attempt to achieve security,

but also to strictly curb the power of the military. The Easter

Rising of 1916 became the first test of the legislation.

General Maxwell, who was sent to Ireland to suppress the rebellion, immediately stretched the ambit of his powers to the limit. He ordered that the trials be conducted by Field General Court Martial: the most rudimentary system of trial for men at the front. He also ordered the trials to take place in camera and without lawyers present. Trials and executions took place in such haste and secrecy that no legal challenge to the legality of what was done could be mounted at that time. Afterwards Prime Minister Asquith asserted that the trials had been conducted according to law, and a test case to challenge their legality failed.⁶ Recent research shows that the statutory protections conferred on prisoners— access to legal advice and to defence witnesses—were not observed. The Judge Advocate General’s post-conviction review was simply bypassed. In the crisis, the law had been stretched beyond breaking point. After the Great War, the Defence of the Realm Act was abolished but a resurgence of fighting in Ireland caused Westminster to pass the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, which created a system of military courts that pervaded every area of life in Ireland.⁷ Under this regime ten men were hanged for involvement in the insurgency, although it is now acknowledged that two of the prisoners (Patrick Maher and Thomas Whelan) had not been involved in the events that had given rise to their trials.

During the final months of the conflict, the British army lost control of much of the south and west. With the consent of Lloyd George, the army bypassed the statutory court martial regime, introducing fast-track military courts to bring about the swift execution of men ‘taken in arms’. By the summer of 1921 fourteen men had been shot by firing squad and, in the Martial Law Area alone, there were forty-four men under sentence of death and dozens more awaiting trial by military courts. By a writ of habeas corpus for one of the death row prisoners, the High Court found these martial law military courts were unlawful.⁸ The executions were paused and almost immediately the truce came about.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in circumstances that are well known and civil war followed; when the crisis came, the Cabinet of the Provisional Government considered whether the Treaty gave power to legislate to create military courts pending the creation of the Irish Free State. It did, explained Attorney General Hugh Kennedy. But there was a catch. Because the Irish Free State had yet to come into being, there was no Governor General to give the necessary royal assent.⁹ If the Provisional Government were to proceed, it would require the personal signature of King George V to create military courts. To avoid this political embarrassment the Provisional Government decided not to enact legislation, and simply brought a motion before the Dáil that lacked any force of law. Assurances were given that prisoners would be fairly treated and would have defence lawyers. As a result, the Army (Special Powers) Resolution (commonly and mistakenly known as the Public Safety Act) was passed by the Dáil on 28 September, but any semblance of due process was quickly abandoned. By the end of the civil war over 1,246 prisoners had been tried by military tribunals, over 400 were under sentence of death and, in addition to the Mountjoy executions, 79 men had been executed. Only a handful were ever allowed a lawyer for their trial. Patrick Hennessey’s last letter home provides a compelling insight: ‘We were tried at midnight…called from our cells where we were asleep, got no chance to defend ourselves’.¹⁰

The Mountjoy executions marked a pivotal moment in the abandonment of the rule of law. Hours before the executions were carried out, General Richard Mulcahy ordered the creation of army committees that would substantially replace military courts, expedite the trial process and make convictions easier to obtain.¹¹

Mulcahy’s decision probably reflected his view that the army was on the verge of a crisis. In fact, the anti-Treaty assassination campaign petered out but Mulcahy’s committee system, conceived in haste, became the norm. These army committees would decide verdicts on the case papers, sometimes without hearing from the accused. For these men, there was no appeal nor any review by the Judge Advocate General and they became part of a growing bank of prisoners under sentence of death.

The criteria for choosing prisoners for execution was

extraordinary: it did not depend on the perceived culpability of

prisoners: anti-Treaty TDs and high-ranking officers captured with

arms were not executed. The executions fell on the junior officers

and rank and file. The policy of the National Army morphed into

reprisal executions—‘in every case of outrage in any

battalion area, three men will be executed’.¹²

When troops were attacked, the army searched through the prisoners

under sentence of death and singled out those who were from the

locality where the ambush had taken place. Executions followed.

Extract from Richard Barrett’s last letter to his family, written from his cell in Mountjoy jail at 2 a.m., 8 December 1922 (Image: Capuchin Archives, 1922: civil war collection; courtesy of the Irish Capuchin Provincial Archives)

The justification for trials by military court rested on the contention that ordinary law had broken down and the army, as Richard Mulcahy asserted, needed to ‘stand in the gap’.¹³ That may have been so in the autumn of 1922 but, as the anti-Treaty faction collapsed the following spring, arguments founded on necessity evaporated. Executions nonetheless continued until well into the summer.

After the war, the government passed the Indemnity Act to protect those who had taken part in military courts and the suppression of the anti-Treaty cause. It did not render lawful what had been done, but it prevented anyone bringing a legal action in response.¹⁴

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.