7 October 1922: The Killing of Teenagers Eamonn Hughes, Brendan Holohan and Joseph Rogers

Trauma and the Legacy of Violence

by Anne Dolan

In the early morning of 7 October 1922 a dairyman found the bodies of two ‘respectably-dressed men’ lying on the side of Monastery Road, Clondalkin; a third was nearby on quarry land. Eamonn Hughes and Brendan Holohan had been shot multiple times, then shot again after falling to the ground. On Joseph Rogers’s body, a doctor counted sixteen wounds. These ‘respectably-dressed men’ were teenagers, sixteen and seventeen years old, identified by their families as studious, religious, hardworking; they were apprentices making their way in the world; they were coming men, the eldest with a cigarette holder in his pocket, a gold ring on his finger and a monogrammed watch on his wrist. After going out together to paste up anti-Treaty handbills, they were seen getting into a car with three National Army officers on Clonliffe Road. What happened between then and when the dairyman found them remains unclear.¹

These deaths, days before the Special Powers Resolution came into force, and over a month before official executions began with the deaths of three more teenagers and a man of twenty-one, have a very particular civil-war context, but they are also part of a longer continuum of violence. Irishmen had been killing Irishmen in this way for well over two years, nearly three, by this point, and perhaps that may explain the assumptions that have been made about these deaths in October 1922. When the killings of Hughes, Holohan and Rogers are mentioned, Charles Dalton’s responsibility is presumed more than proved. These deaths are taken as a type of unfortunate proof of the toll all he had seen and done since becoming a Volunteer at the age of fourteen had taken on him by 1922. Although two other army officers, Nicholas Tobin and Sean O’Connell, were with Dalton on Clonliffe Road, Dalton, the one-time GHQ intelligence officer and by then commandant in the new state’s army, had the reputation to fit a very particular understanding of violence, one that rather neatly supposes that Hughes, Holohan and Rogers were victims of how one young man had been brutalised by his war.

This view of Dalton has been confirmed since the release of his military service pension application. While he was a patient in St Patrick’s and Grangegorman hospitals between 1939 and 1943, doctors wrote that ‘his impressions and hallucinations’ all ‘referred back to those earlier years’; that he was ‘hearing voices which accuse him of murder’; that ‘his own active part…preyed on his mind and conscience so that in the following years he has gradually lost his reason’. One old comrade, Frank Saurin, reminded the pension assessors that Dalton ‘was a mere school-boy when he commenced his career as a “gun-man”’, and that he had once found Dalton cowering from ‘imaginary potential executioners’ in his own home. The same file notes the time Dalton spent in different hospitals and the worry of his wife, with four young children, who sought assistance in 1940 for the medical treatment that she could not afford.

Dalton’s file has become noteworthy because an old civil-war opponent, Seán Lemass, took the time when minister for supplies in wartime 1941 to pen a five-page, hand-written letter in support of Dalton’s case, but even more so because his file provides medical evidence of ‘postcombat stress and despair’ amongst those who fought.² Because Dalton’s application is not the only one, because there are others who describe what they endured as ‘shell-shock’ or ‘neurasthenia’, because more stumble it out as ‘nerves went astray after’ or ‘cracked up as a consequence’, assumptions have been made—extrapolating from the experience of some to the many—that ‘one of the major themes of the aftermath of the revolution is…trauma’.³ Such a conclusion is not, however, without its challenges and its consequences.

Having reviewed the psychiatric files of 450 German veterans of the Second World War, Svenja Goltermann argues that ‘the concept of “trauma” is a problematic tool for historians’, and she even refuses to use it ‘on the grounds of anachronism’. Goltermann’s reservations reflect the contested nature of trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder within the fields of psychology and psychiatry certainly, but also her unwillingness to pronounce beyond her capacity as a historian.⁴ Psychiatrists would hesitate to diagnose trauma without direct clinical examination of their patients, so should historians be so quick to pathologise? Joanna Bourke has argued that ‘the cultural history of warfare’ has become ‘obsessed with trauma’, despite ‘the fact that most men coped remarkably well with the demands being made upon them in wartime’. Nigel Hunt has gone further, suggesting that ‘we have now almost reached the stage where we expect people to break down after a traumatic event, and there is something wrong if they do not’; that silence is read too straightforwardly as anguish. For Yuval Harari, the ‘soldier-as-victim’ of ‘the psychological damage’ of war is now so ubiquitous as to be ‘clichéd’.⁵ Dalton is one very specific case, with very clear clinical evidence, but his pension application speaks eloquently of no one else’s distress but his own.

Crucially, distress was not his only response. He left hospital; he went home; he wrote newspaper articles about his war; he finished his Bureau of Military History statement in 1950 cherishing the ‘very strong spirit of comradeship’ that survived long beyond 1922.⁶ His relationship with his own past was neither static nor clear. Given that what was intended to be private has been made public in the release of his and other pension applications, it begs questions about what historians can assume to write about another’s torment in the past. But the ethical challenges are broader than that. C.F. Alford argues that trauma ‘helps us see the world through the victim’s eyes’, and Dalton comes from the pages of his application as a victim of what happened to him, of what he was made do; barely even an actor in his own wars.⁷ It is a concern that troubles some historians of violence who, in response to the expansion of victimhood to include war’s perpetrators, urge ‘differentiation between the experiences of perpetrators, victims, and bystanders, as both an ethical and historical imperative’.⁸ Unfortunately, perpetrators and victims are not always as easy to disentangle as that.

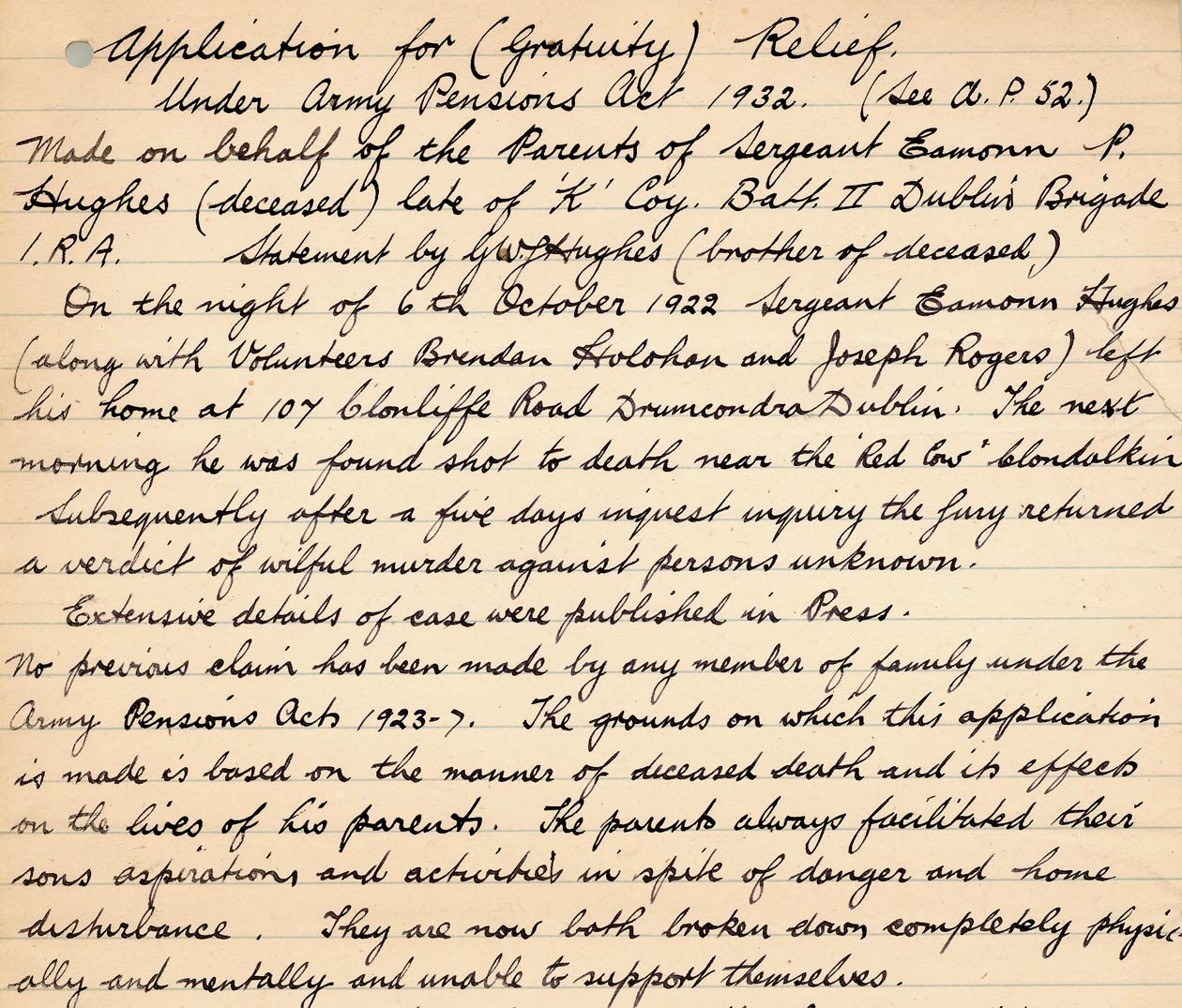

Indeed, Dalton captures the challenge of this. While he strikes a sympathetic figure in his own application, so too do the parents of Eamonn Hughes when an application was made on their behalf for a dependents’ allowance. Described as ‘both broken down completely physically and mentally’, Mark Hughes was the clerk who could no longer work, Annie Hughes the music teacher who could no longer teach, because their teenage son had been killed, possibly by Charles Dalton, on 7 October 1922. In 1933 the Pension Board was requested not to even send letters about the application to their home, because ‘mention of his name to them would serve no good purpose’; over a decade after they still could not bear reference to the circumstance of their son’s death.⁹

If trauma is to be a means to consider the long-term consequences of violence, is it an agile enough concept to accommodate Eamonn Hughes’s parents alongside Dalton? Given what can now be known from the sources, historians incur responsibilities ‘when resurrecting the pain and suffering of people in the past’.¹⁰ In light of what remains unknown, Dalton and the Hughes should be left to speak for no one but themselves.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.