7 December 1922: Ulster Opts Out of the Irish Free State

Partition and Power: Unionist Political Culture in Northern Ireland

by Robert Lynch

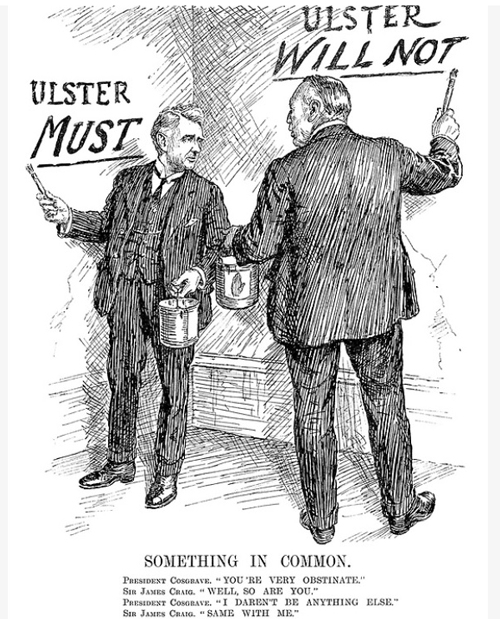

On the evening of 7 December 1922 the prime minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, set sail from Belfast to deliver his parliament’s decision, made only that afternoon, to opt out of the newly created Irish Free State. There had been no need to hurry. By the terms of Article 14 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the northern parliament had a month to make its choice, but Craig was anxious ‘not to show the slightest hesitation to the world’ of his government’s rejection of the separatist nationalist project.¹ As one of his MPs observed in the brief debate a few hours earlier, Ulster’s decision was akin to that of a lifeboat readying itself to escape a sinking ship.

That the new Irish Free State was imploding seemed self-evident. The next morning as Craig arrived in London to present his humble petition, the Free State government ordered the summary execution of four republican prisoners in Dublin in retaliation for a fatal attack on a TD the previous day, beginning a journey into the darkness of political authoritarianism, arbitrary arrest and state-sponsored murder.

It was a journey Craig knew well. Only six months earlier his own government had used similarly repressive methods to end its own undeclared civil war, after withstanding two years of violence and political opposition from southern nationalists and a recalcitrant minority within its own borders.²

Like the southern state, Northern Ireland was crippled both materially and psychologically by the traumatic civil war that marked its birth. Its experience was hardly unique in the context of post-war Europe, however. Most of the newly formed successor states wrestled with sizeable and troublesome minorities, and in many ways Northern Ireland had significant advantages over its continental neighbours. It had a strong industrial base, a history of representative democracy and a sizeable middle class ready to staff the new state’s institutions. Added to that was the existence of a powerful neighbour ready to provide financial, political and military support in time of crisis.

Yet such advantages did not lead to compromise. In contrast to its southern neighbour, Craig’s government remained in an almost permanent state of emergency, retaining its costly and repressive security apparatus and supporting tens of thousands of auxiliary police reservists. Its ageing leadership, veterans of the bitter struggles against Home Rule, contained few visionaries or progressives. Attempts to secularise the education system united both Protestant and Catholic church leaders in opposition, while initiatives to include more Catholics in the police or civil service met fierce resistance in Cabinet and from bodies such as the Ulster Protestant Voter’s Defence Association, ever vigilant to protect their rights and root out ‘disloyal elements’ at the heart of government. The Catholic minority was to be tolerated but kept away from the levers of power. Craig’s administration set about nullifying minority political influence almost immediately by targeting recalcitrant nationalist councils that refused to recognise the new Belfast regime. In September 1922 the Northern Ireland government passed into law a bill abolishing proportional representation in local council elections, redrawing boundaries with meticulous care to ensure wards would provide an overall unionist majority. Fatally, nationalists—still wedded to the doctrine of non-recognition and abstention—remained aloof from the process, allowing unionists to dictate the future political geography of the state. The result was that the number of opposition-controlled councils fell from 27 in 1920 to a mere 12 seven years later.

No nationalist of any hue took their seat in the Northern Ireland parliament until 1925. Even then the Nationalist Party, representing as it did a profoundly divided and disillusioned minority, refused to become the official opposition. Unionists remained deeply suspicious of the motives of Nationalist MPs no matter how conservative or constitutionally minded they were, leading eventually to the abandonment of proportional representation for national elections too. That bill, championed by Craig as early as 1922, was eventually enacted in February 1929, a mere three months prior to the next election; it successfully squeezed out smaller parties and reasserted unionist dominance for the next 40 years. For Craig, politics was a blunt weapon for maintaining power and crushing dissent, rather than a means of facilitating progressive democratic reform.³ The result was that politics began to ossify. Previously vibrant grassroots organisations withered and died. In 1925 only 8 of the 52 parliamentary seats were uncontested but by 1933 this number had risen to 33. Nationalists had been so successfully marginalised by the state that, when the new parliament buildings were opened at Stormont in 1932, they did not even bother to attend.

Craig’s role then was more akin to that of a president than a prime minister, and he enjoyed majorities more secure than most European leaders of the time. This hegemony was maintained not by a programme of political reform but by a defensive and wearisome inertia. The average unionist MP was ageing, reactionary and, if the records of the parliamentary debates are anything to go by, embarrassingly inarticulate and ill-informed.

Government sank into a curiously dysfunctional stasis, marked by trivial debates and inactivity. There were remarkably few private members’ bills and with periods of parliamentary recess longer than those at Westminster, the parliament when it did meet spent most of its time duplicating Whitehall legislation or receiving deputations from local unionist associations concerned about the growing influence of ‘disloyal elements’ in their local areas.

Political complacency was reinforced by the severe financial restraints within which Northern Ireland operated. Even had there been an impetus for an energetic state-building programme, the state was effectively broke. Ironically, considering the centrality that economic arguments had played in unionist propaganda since the late nineteenth century, almost as soon as the state was founded it went into a severe economic decline.

The reason for this could not be blamed on the new border or government inefficiency. Rather, Ulster fell victim to the chronic problem of oversupply in the post-war global economy. In 1922 few people wanted what Northern Ireland was selling. Prices for linen fell to 35% of their wartime level, and unemployment in the industry rose to 32% by 1927. Shipbuilding suffered a similar fate. The number of workers at Harland and Wolff fell from a height of 30,000 during the Ulster Crisis to a mere 1,500 by 1932, while the other major shipyard in the city, Workman Clark, closed altogether. By 1922 unemployment stood at 23% of insured workers, and for the rest of the decade an average of one in five would be without a job. Endemic poverty resulted, and Northern Ireland became consistently the poorest region in the United Kingdom. In such an environment what privilege there was, both political and economic, was jealously guarded.

The dysfunctional nature of the northern state had much to do with limitations in the mindset of its chief architects. For all their bluster and threats of revolt, Ulster unionists had never sought, or expected to run, a parliament of their own. They had reluctantly accepted the partition idea, although with little seeming comprehension of what such a decision would entail. Certainly, as Craig made his journey that cold December night he could congratulate himself on accomplishing his overriding goal of ‘saving Ulster’. While he and his colleagues had much-rehearsed ideas of what they had saved it from, however, they had little seeming interest in what exactly they had saved it for.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.