6 February 1922: Pius XI Ascends to the Papacy

Religion, Graffiti and Political Imprisonment

By Laura McAtackney

Pius XI’s papal reign (1922–39) officially began on 6 February 1922. It may seem an unlikely event to tie into Irish history, but there are a number of compelling reasons as to why it is a date of symbolic and material value. The role of religion in the so-called revolutionary period has been explored in a number of ways by historians. In recent years there have been contentious debates about the role of religious sectarianism in the targeting of people and places in the south of Ireland during the War of Independence and the civil war.¹ In the north of Ireland, the ‘Belfast pogroms’ (1920–22) and associated civil disturbances, riots and orchestrated attacks demonstrably had a sectarian motive, with religion functioning primarily as an identifier. There have also been thoughtful reflections on the role of rank-and-file priests, as well as the policies of the Catholic hierarchy, in their active support or rejection of the various sides during the conflict.²

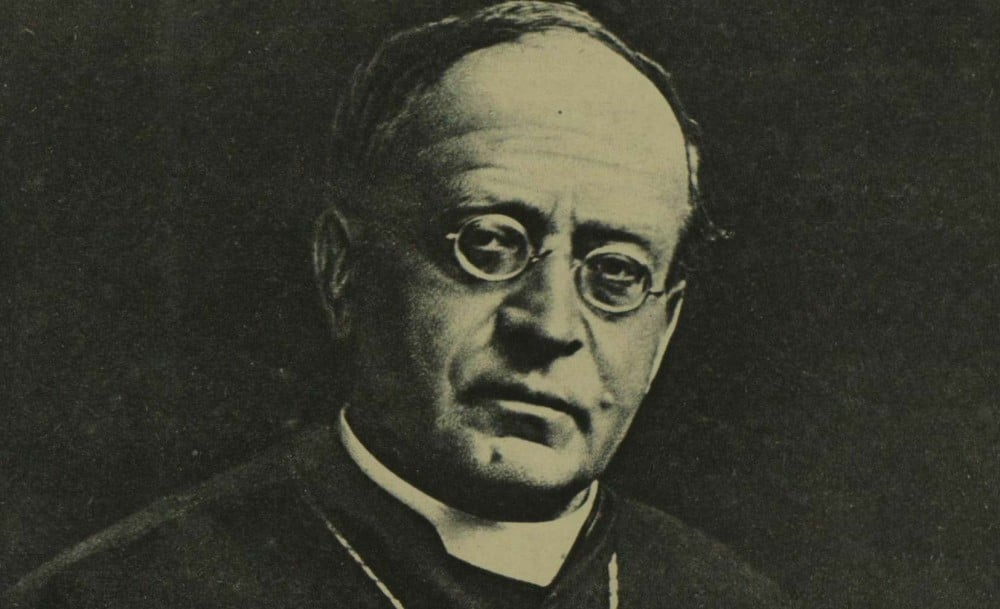

From the perspective of combatants, Michael McCabe has argued that the anti-Treaty forces made claim to the moral high ground in their rejection of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.³ Eventually, this claim was categorically contradicted by the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in Ireland through the bishops’ pastoral letter of 22 October 1922, which unambiguously condemned the violence of the anti-Treaty forces. In response to spiritual sanctions against them, ranging from refusal to provide communion or absolution to excommunication, the anti-Treaty forces looked outside of Ireland, specifically to the Vatican, for moral and institutional support. By the end of 1922, the figure of Pope Pius XI did not simply represent the highest level of the Roman Catholic Church, he was also the ultimate court of spiritual appeal to both sides. Arthur Clery and Conn Murphy made a direct appeal against the October pastoral to Pope Pius XI, and as a result Monsignor Salvatore Luzio arrived as papal envoy in March 1923. His mandate was to investigate the situation in Ireland, much to the hostility of the Irish bishops.

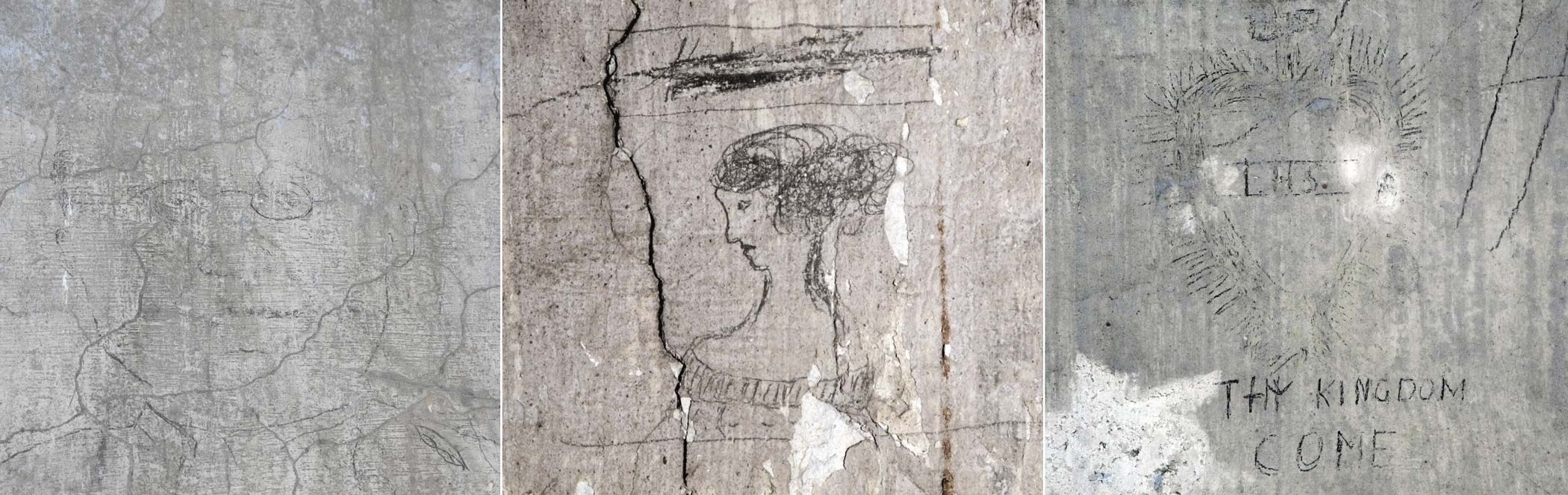

The desperate nature of republican appeals to the new pope became materially manifest in what is now itself almost a holy relic of the revolutionary period—Kilmainham Gaol. During an extensive survey of historic graffiti in the building (initially funded by the Irish Research Council in 2012–14 on the West Wing of the gaol; extended by the Office of Public Works to the East Wing and Courthouse in 2015), a portrait of Pope Pius XI was located. This is not entirely unusual—religious iconography dating from the civil war period was common throughout the prison cells—but no portrait or other depiction of any other identifiable member of the Roman Catholic Church was discovered during the entire survey.⁴ The location of the portrait of the pope was also unusual. It was only during a supplementary phase of recording that a long-locked room on the top floor of the Administrative area was opened to reveal an extant assemblage of various forms of graffiti—text, portraits and shapes, mainly in pencil—spread across all of the room’s walls. While the assemblage was not numerically extensive—65 separate pieces of graffiti were recorded—the contents of the room were unusual, and featured examples not recorded elsewhere in the building. Most of the graffiti remaining in the room appear to have been created contemporaneously, and the most prominent examples were strategically located: two framed portraits were located beside the door and one was above the fireplace.

Pope Pius XI (Image: Illustrated London News [London, England], 11 February 1922)

The portrait of Pope Pius XI was the centre-piece of the room, situated above the fireplace and drawn with an elaborate trompe l’oeil oval frame. There is no signature associated with the portrait so it is impossible to know for sure who created this image, but there are some clues. First, this graffito was not located in the cell blocks, where the majority of the thousands of examples of civil war graffiti remain. It was inscribed on the wall in what is known as ‘Debtors Room 1’, which is a large, rectangular room with sash windows and a fireplace, far away from the prisoners’ wings and cells. This room would not have been used to hold ‘ordinary’ prisoners during the revolutionary period, but probably to isolate exceptional individuals, particularly leaders and/or hunger strikers. The portrait of Pope Pius XI is not the only portrait in the room—there are five extant portraits; two have been whitewashed and another is partially hidden under the pope’s portrait—but it is the only datable piece of graffiti by virtue of having a terminus post quem of 6 February 1922.

The surviving graffiti at Kilmainham Gaol are an important source for revealing lived experiences of the civil war.⁵ This is especially the case for women who were interned in the gaol for periods from November 1922 to April 1923, and who left many marks,⁶ but are less prominently recalled in public memory.⁷ Most of the gaol’s extant pieces of graffiti are contained in the West Wing, but their survival does not simply correlate to where graffiti were originally created; rather, it reflects decisions made by the Kilmainham Jail Restoration Society. Meeting notes from 1958 reveal that the old IRA committee would only support the restoration of the prison if ‘nothing of or relating to the period after 1921 would be identified with the Kilmainham project’.⁸ While the restoration committee focused on the East Wing, they removed most of the plastered walls and with them the majority of the post-1921 graffiti (only seven cells have even partial walls intact). The relative neglect of the West Wing to early restoration efforts ensures its graffiti survive better. There is evidence of targeted whitewashing of graffiti (including in Debtors Room 1), often because of references to sensitive matters relating to the civil war (mainly partition and executions), but this is minimal.

While depictions of Pope Pius XI have not been found elsewhere in the prison, there are textual and pictorial references to religion in every corridor in the West Wing. The most common forms of religious graffiti are crosses or crucifixes, from simple, engraved, hatched crosses through to elaborate, stepped, cruciform monuments. The most well-known piece of religious graffiti in the prison, the mural of Mary and Child created by Grace Gifford Plunkett in the East Wing, survives (although extensively ‘restored’); the large altar mural she created has, however, long disappeared. There are ornate and intricate religious graffiti that persist in the West Wing, but nothing that matches the scale or extent of Grace Gifford’s murals. Rather, a range of small crosses, monuments, prayers and even an ornate Sacred Heart with the words ‘Thy Kingdom Come’, remain as material indicators of the religious sentiments of the anti-Treaty prisoners.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.