4 March 1922: The Wife of a Plasterer Tells the Archbishop of Dublin a Secret

Gender and Poverty in the New ‘Free State’

By Lindsey Earner-Byrne

Dear Archbishop

I humbly ask pardon for the liberty I take of writing to you + also hope you will excuse me as I don’t know how to address you I am the wife of a plasterer + we have 7 children the eldest only 14 years old.¹

On the 4 March 1922 Mrs Anna Lalor* was heartbroken. Little had changed in the previous two years for her family of nine; if anything, things had got worse. Indeed, on this morning she felt compelled to sit down in her overcrowded two-roomed house in Dún Laoghaire, County Dublin, to write to one of the most powerful men in her universe—the Roman Catholic archbishop of Dublin, Edward Byrne (1921–40). Her letter is but one among thousands the archbishop received: these letters represent an extensive archive of the experience of poverty in the first two decades of Irish independence.

According to the 1901 census, prior to marriage Mrs Lalor had been a domestic servant, an occupation she shared with one in three single women: domestic service remained the biggest single employer of women in Ireland until the 1950s. In 1907 she left the formal workplace to marry, thereby entering a period in her life when little was within her control, not her fertility nor the waxing and waning of her husband’s earning capacity. The meaning of this impotence must have become apparent quite quickly to her: within four years she had birthed three children, almost one a year. By 1922 Anna had seven children; the maths of seven children in fifteen years indicates that some of the gaps were miscarriages or infant deaths. Infant mortality was still disturbingly high in 1920s Ireland, and it was a clear barometer of social inequality mapping closely to the geography of class. The 1926 census revealed that Dublin city had an infant mortality rate of 170 per 1,000 births, compared to 79 per 1,000 in the affluent, seaside Dublin village of Howth.² Despite the knowledge that multiple pregnancies increased infant mortality and maternal morbidity, birth control was criminalised in 1935.

The spacing in Mrs Lalor’s brood also reflected the geography of her husband’s work-life, as she explained:

last October twelve months, there was a strike declared in the Building Trades in Dublin and at the very time I was in Bed seriously ill my husband was forced to go to England to get Bread for his children leaving me heartbroken as I was so ill, he got work in England + was allowed to join the English Trades Union for the sum of 8d with a lot more Irish men.

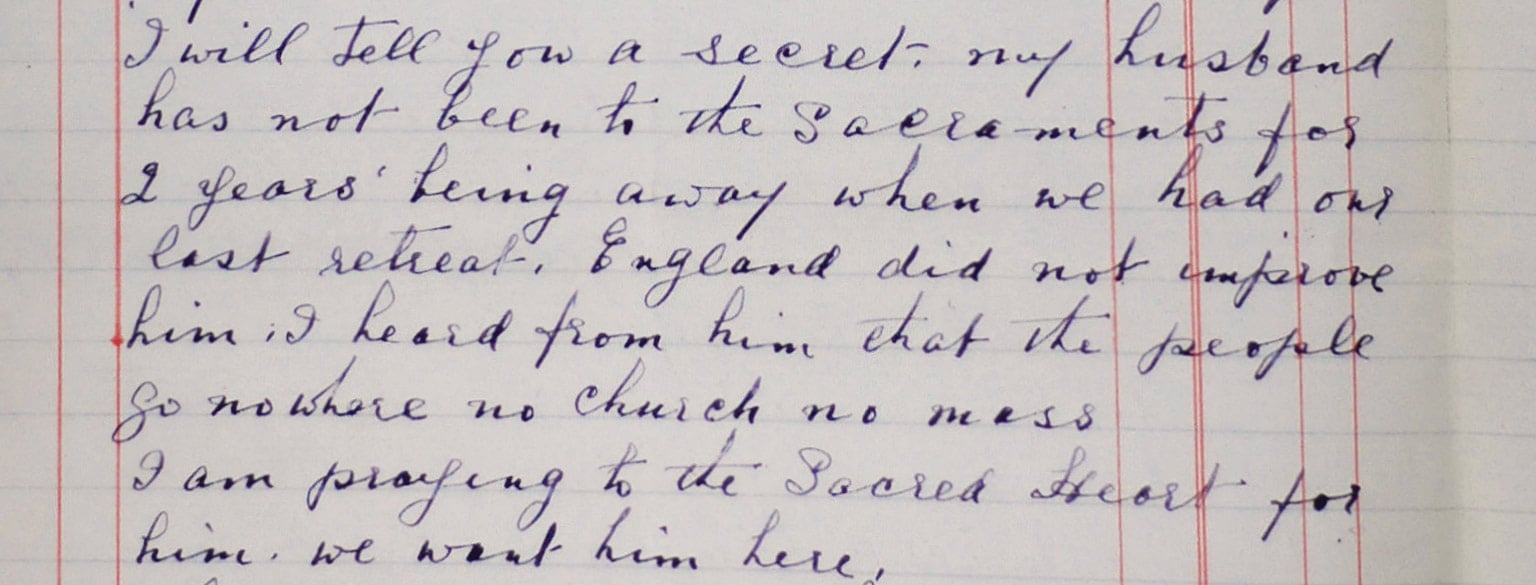

An excerpt from the letter of Mrs A.L., Desmond Avenue, Dún Laoghaire, (Co. Avenue), to Archbishop Byrne, 4 March 1922 (Image: Dublin Diocesan Archives, Byrne papers, Charity cases, box 1: 1921–26. Reporduced courtesy of Dublin Diocesan Archives)

The unemployment rate in the building sector was 34 per cent, with 32 per cent of workdays lost through strikes.³ She was referring to the bricklayers’ strike in Dublin that had lasted between October 1920 and June 1921. The strike had only secured the workers a temporary increase of 1d per hour, while ‘keeping the city’s modest slum clearance programme on hold’.⁴ That outcome was indicative of the false promise of political independence for the new Ireland’s poorest citizens. While the president of the Executive Council, William T. Cosgrave, oversaw welfare cuts, including to the Old Age Pension, he drew an annual salary of £2,500.⁵ The average industrial wage was £126 per annum.

The new state promoted with vigour the stay-at-home mother as the bedrock of society; women like Mrs Lalor, however, could rarely afford such idealism. The poor continued to survive through seasonal migration and emigration, largely to England. Mrs Lalor articulated the emotional cost of that strategy, deftly connecting it with a sense that political freedom was a ruse that would not feed her children:

my husband Keeps saying this is free Ireland the Englishman can give the Irishman liberty to earn Bread for his family for 8d per week while the Irishman who is supposed to be good roman catholic christians demand £5 to get liberty to work in their own country.

She was referring to a £5 penalty her husband’s union had imposed on workers who had not returned to Ireland upon the resolution of the strike. This occurred, she explained, even though her husband had regularly sent ‘strike money’ to the ‘Dublin Trade Union’. To her the trade unions were just another source ‘taking the Bread from my children’ with their fees and penalties. She was also appealing to her Church’s dread of socialism, while placing those ‘supposed to be good’ Catholics at the centre of a narrative of social injustice and hypocrisy. By contrast, she portrayed her faith as central to her ability to cope:

I was unhappy all the time being separated from my husband while he was also in the beginning, but later he seemed not to mind while my children + myself were praying hard for God to send him home. I wrote to the poor Clares + told them my trouble + asked them to pray also last christmas my husband came home + I prayed + tryed to [--------] persuade my husband to remain with me + the children

With a hint of where her husband’s growing acceptance of separation might lead, she proceeded to tap into deep contemporary anxieties regarding the faith of Irish emigrants in England:

Most Rev. Archbishop I will tell you a secret my husband has not been to the Sacraments for 2 years being away when we had our last retreat. England did not improve him, I heard from him that the people go nowhere no church no mass I am praying to the Sacred Heart for him we want him here.

The en passant mention of ‘our last retreat’ underscore her spiritual dominion over the seven little souls she was sheltering.

Mrs Lalor’s letter provides barely a hint of the violence and uncertainty swirling around her country, for she represents the continuity of human experience, which does not always beat to the rhythm of historical periodisation. The challenge of feeding a family changed little for women like her. Despite her mention of ill health, Mrs Lalor outlived her husband by 23 years, dying in December 1974. During her lifetime the structure and trajectory of social inequality remained largely unchanged: the children of the poor continued to be the parents of the disadvantaged. In the intimate relationship Mrs Lalor conjured in her letter, the Catholic archbishop became both her confidante and trusted friend: ‘my husband Knows nothing about me writing … Most Rev. Father again excuse me I could not trust anyone else’. While she feared she was ‘doing a Terrible thing in writing’, she was also ‘sure that you will try to do something’. She wanted him to use his influence to change a system that condemned people like her to live as she did. In asking for nothing specific, she asked for everything in spirit. She already knew what, a year prior to her death, the 1973 report of the Commission on the Status of Women in Ireland laid bare: power is always measured in pounds and pence.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.