4 January 1922: The Treaty Debates

The Politics of Emotions

By Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid

On 4 January 1922 the cool concrete façade of Earlsfort Terrace in Dublin concealed a pressure-cooker atmosphere as the debates over the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty approached a conclusion. Seán O’Mahony, TD for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, made an emotional appeal to the ‘youth of the Irish Republican Army’ who, he declared, ‘had proved themselves too straight, too true, too unselfish in their love and loyalty to the Republic to be decoyed from the path of honour, or righteousness and of duty’, unlike those who, he claimed, ‘live in trembling’ and would ‘bend the knee and sign their rights away’.¹ O’Mahony’s intervention that day encapsulated key features of the Treaty debates: opening with a joke, prompting laughter, but moving swiftly to invoke strong emotions—love, loyalty, fear, betrayal—and ending with a round of applause. These debates of course have long featured as a climactic point in the history of the Irish revolution: the moment when the fraternal camaraderie of the republican movement was fractured, ushering in the bitterness and divisions of the civil war. An ‘avalanche of oratory’ akin to O’Mahony’s was unleashed, in support of and against the proposed Treaty.²

The contours of the debate have attracted sustained historiographical attention, not least elsewhere in this volume, with particular attention paid to the weighing of the constitutional arguments on either side, the gendered dynamics and, latterly, the class dimensions of the Treaty split.³ But alongside questions of constitutional integrity and competing conceptions of republican liberty, the most oft-noted feature of the Treaty debates was the tenor of the exchanges. The mood at the lecture halls at University Buildings was frequently underlined, from the cheers of the waiting crowd outside as deputies entered, to the tension, gravity and gloom that progressively engulfed the debates themselves. These debates unfolded in a curious mixture of publicity and privacy: the public sessions were avidly reported in the national and provincial press, with particular attention paid to the tone and mood of the chamber, while even the comings and goings to the closed sessions were closely followed for hints of the debates’ progress. The emotional register of the Treaty debates thus formed a significant part of how the Irish public learned about the emerging split in the republican movement.

Despite the bitterness, which was the abiding memory of the debates, the emotion most frequently expressed in the debates themselves was love—of Ireland, and of each other. Patriotic flourishes coloured many of the contributions. Seán Mac Eoin declared:

I say I am an extremist, but it means that I have an extreme love of my country. It was love of my country that made me and every other Irishman take up arms to defend her. It was love of my country that made me ready, and every other Irishman ready, to die for her if necessary.⁴

Mary MacSwiney affirmed, ‘I love my people, every single one of them; I love the country, and I have faith in the people.’ Declarations of love, friendship and admiration for each other were also evident: Arthur Griffith, anxious to minimise the depth of the impending split after the results of the vote on the Treaty were known, emphasised that ‘there is scarcely a man I have ever met in my life that I have more love and respect for than President de Valera’, while Collins emphasised de Valera’s ‘position in my heart’.

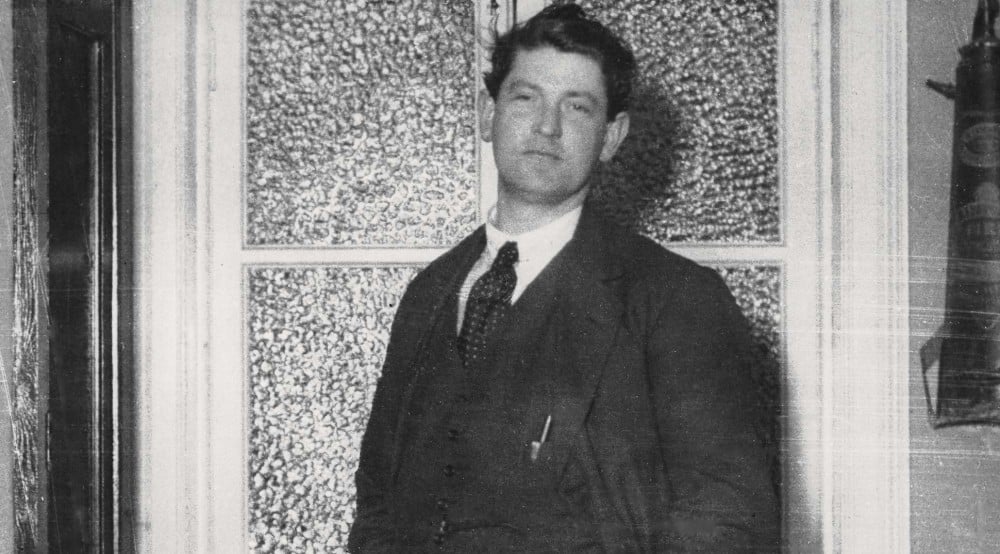

Michael Collins at the Gresham Hotel, Dublin, the night the Treaty was ratified (Image: NLI)

Successive speakers invoked patriots of the past—the sacred trio of Tone, Mitchel, Davis—and as the urge grew to maintain unity in the face of the rapidly deepening fissures, the bona fides of both sides of the divide were emphasised: Éamonn Duggan underlined that ‘there is no monopoly of patriotism on either side of this house’. This rattling of the bones of the patriot dead grew more noisy as recent martyrs were invoked, largely in favour of rejecting the Treaty. Piaras Béaslaí enlisted his ‘dearest friend Seán MacDiarmada [who] loved Ireland just as Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith love Ireland’. Kathleen Clarke spoke of her last visit to her husband in Kilmainham in (for her) unusually emotional terms:

though sorrow was in my heart, I gloried in him, and I have gloried in the men who have carried on the fight since; every one of them. I believe that even if they take a wrong turn now they will be brave enough to turn back when they discover it. I have sorrow in my heart now, but I don’t despair; I never shall.⁵

Margaret Pearse ventriloquised her son Patrick, admitting that ‘the Black and Tans alone would not frighten me as much as if I accepted that Treaty: because I feel in my heart—and I would not say it only I feel it—that the ghosts of my sons would haunt me.’⁶

More negative emotions were also openly expressed. Daniel O’Rourke declared he would ‘yield to no man in his hatred of British oppression’ (before voting in favour of acceptance); Constance Markievicz ‘despised’ what she saw as the Treaty’s attempt to entrench privilege in the so-called Free State; while Seán T. O’Kelly underlined the ‘accursed union…which we shall never cease to detest and to loathe’. Fear was present too: it stalked the chamber. The prospect of a split and of sundering the political community which had been forged through the revolutionary process was uppermost in deputies’ minds and was a recurrent if implicit emotion throughout the debates. Joseph McBride voiced the precedent many must have been thinking of—‘the foul implications and the degradation of the Parnell split’—while another O’Rourke stressed he was ‘quite prepared to do anything for unity because the curse of this country has been disunion.’ Éamon de Valera, in one of several highly emotive outbursts, denounced his political opponents as ‘trying to make out that I am trying to split the country…to put on me…to represent me as trying to prevent unity’. Some accused their opponents of being motivated by fear—Liam Mellows, a staunch anti-treatyite, claimed that ‘it is not the will of the people but the fear of the people’ that propelled the pro-treaty arguments—while others were adamant that the people in Ireland were steadfast and fearless in spite of the terror that was waged against them.

The lecture hall at Earlsfort Terrace was also a performative space: deputies used and transgressed the formalities of parliamentary procedure to reinforce the emotional weight of their arguments. In this heightened atmosphere, feelings bubbled over and passions ran high. Reading the extremely well-detailed transcript of the debates, the heated nature of the exchanges is immediately apparent, as well as the degree to which the Dáil transcribers wished to preserve the emotional tenor of the Great Debate. There were multiple bursts of applause, surprisingly frequent breaks of laughter, cheers and counter-cheers, cries of ‘hear-hear’ and ‘No!’. This fevered emotional environment also was reflected in the tenor of many of the speeches. The bitterness and anger has been much commented upon: notably Brugha’s railing against Collins, in which clearly his personal dislike bled into his political opposition, or Arthur Griffith’s tetchy and bad-tempered responses throughout, encapsulated in his dismissal of Erskine Childers as a ‘damned Englishman’. De Valera made lengthy statements detailing his outrage, and famously broke down in his statement to the Dáil after the Treaty was narrowly accepted. Michael Collins, de Valera’s chief political opponent, is equally interesting in terms of his emotional responses to the heated and frequently highly personalised debates; as Jason Knirck has pointed out, Collins tended to favour multiple sarcastic, offhand interjections, rather than lengthy defences of his own position.

Todd Andrews, a junior IRA officer watching the final vote from the doorway of the Council chamber, noted that the result was received with a mixture of ‘triumph, grief and worry’.⁷ De Búrca gave more colour to the ‘awful scene’, with women weeping openly and men ‘trying to restrain their tears’.⁸ A feature of the disintegration of republican unity in the months leading up to the outbreak of civil war is the spilling over into the public sphere of the emotional tenor of these Treaty debates—recrimination, anger, accusations of bad faith, pragmatism, and hope. This complex bundle of emotions can all be charted in the public statements made by both sides as Ireland slid towards fraternal conflict. Assessing the Treaty debates as a decisive moment in the emotional history of the Irish revolution thus opens up new ways of thinking about how emotions were expressed and instrumentalised as a means to bolster or undermine political arguments throughout the revolutionary period.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.