29 May 1922: The Arrest of John O Donnell

Internment In Northern Ireland

by Anne-Marie McInerney

On 29 May 1922 John O Donnell was arrested following a crackdown on republican and nationalist activists in Northern Ireland. O Donnell, who had been a Volunteer in the Belfast IRA during the turbulent 1918–23 years, was imprisoned on the HMS Argenta until October 1923, when he was released in a ‘dying state’.¹ By June 1925 he had succumbed to tuberculosis. His widow, Bridget O Donnell, penned a letter in 1932 to the minister for defence, Frank Aiken, applying for her dead husband’s military service pension. Bridget related how John was ‘unable to follow his usual occupation as dock labourer’ following his release from the Argenta.² It was stated that he had been ‘in perfect health previous to his internment’, and his pension statement recorded that he died as a result of ‘brutal and inhuman treatment’ while on the ship. John O Donnell was not the only prisoner to suffer ill-health following internment on the HMS Argenta. Many of those interned on the ship would suffer the effects of their imprisonment for the rest of their lives.³

Internment was a feature of the Irish revolutionary years 1916–21 and continued during the Irish civil war of 1922–23. In Northern Ireland, David Fitzpatrick noted that political and sectarian violence peaked in early 1922, when some 300 murders were officially accounted for. As intercommunal violence increased, the Belfast administration introduced the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act in April. This provided the government with the powers to arrest and intern individuals whom it considered were acting in a manner prejudicial to the state.⁴ What prompted the government to introduce wide-scale internment, however, was the assassination of the Unionist MP William Twaddell in May 1922. On the night of 22–23 May the authorities conducted sweeping arrests in Northern Ireland. Within a few weeks, some 300 persons, ‘almost all Roman Catholic males’, had been detained and served with internment orders. As the administration had only three prisons at its disposal (Derry jail, Belfast jail and Armagh prison), it purchased the Argenta and acquired Larne workhouse in order to meet the accommodation needs of the rising internee population.⁵

Originally named the SS Argenta, this wooden steamer vessel was built in 1917 by the United States and launched in May 1919. Initially used as a cargo ship, the Argenta was purchased by the Belfast administration in May 1922, despite having been declared ‘unseaworthy’.⁶ The hard-line minister for home affairs, Sir Richard Dawson Bates, who specifically purchased the ship to ease the burden on the other state prisons, was hopeful that the prison ship would act as a deterrent for future political offenders. Observing that internees had become ‘accustomed to enjoying the luxury of an internment camp’, he remarked that prisoners would find the ship not quite so ‘pleasant’, and that many of the men had tried ‘to avoid going on a ship’.⁷ By 9 September 1922 there were around 340 internees on the now HMS Argenta. Bates acknowledged that many of these had not been tried and were, in fact, ‘un-convicted’ prisoners.⁸

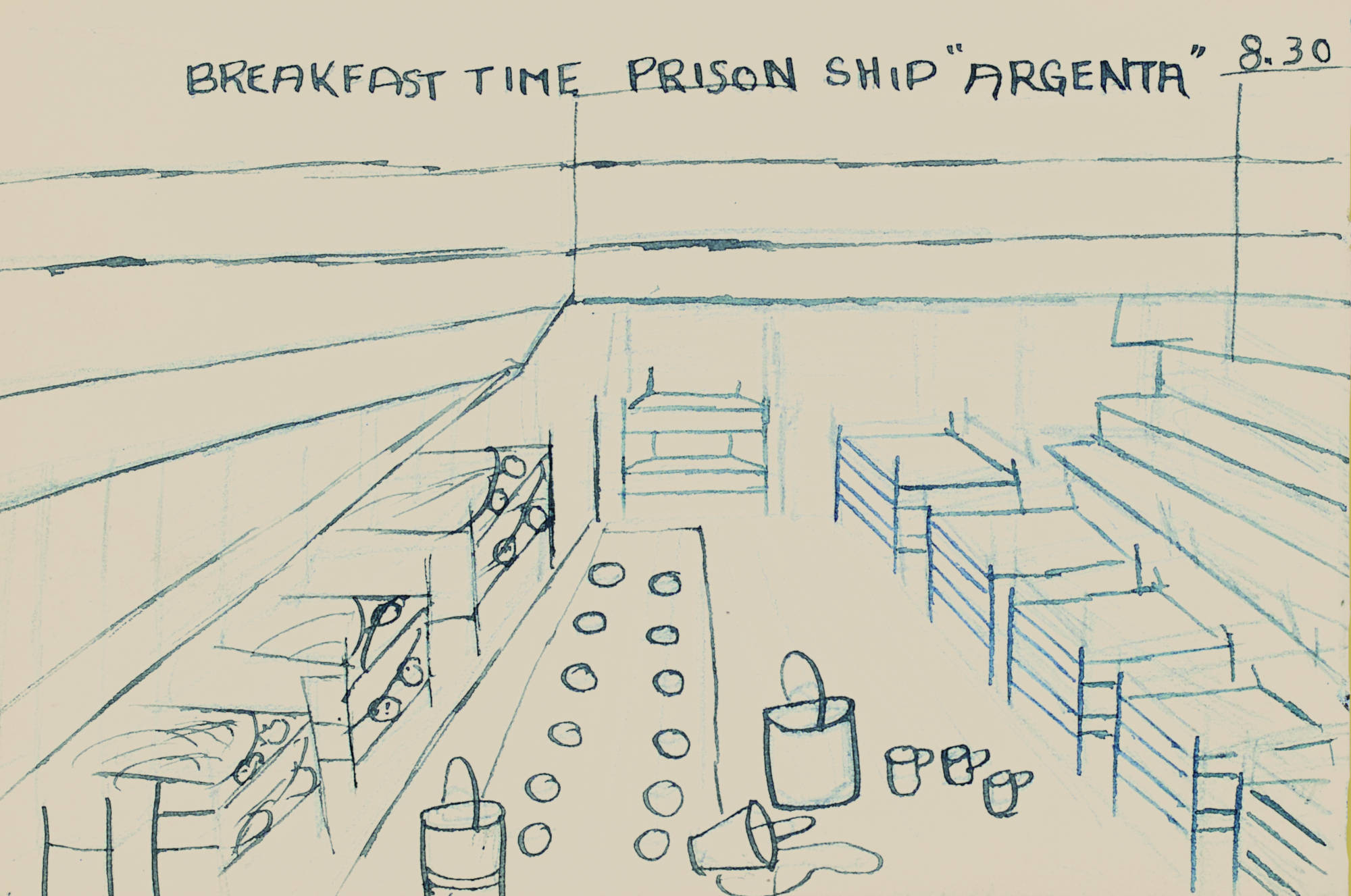

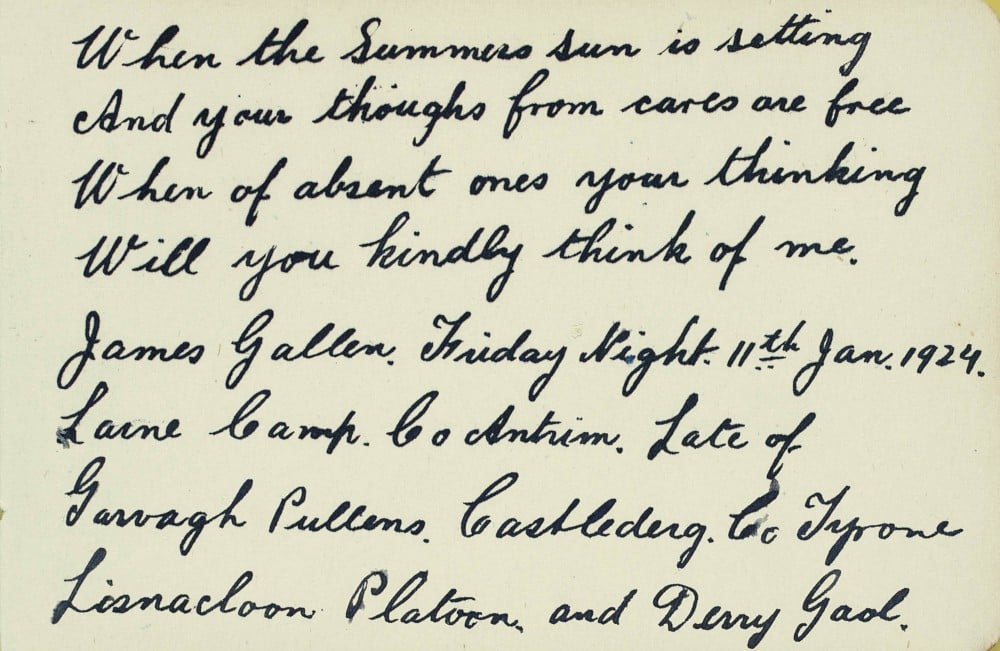

Another page from the autograph book of an internee imprisoned on the HMS Argenta, Belfast Lough,1922–24 (Image: NLI, MS 50,137; courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

Conditions on the HMS Argenta were significantly harsher than those experienced in internment camps, as prisoners were held in eight wire cages below deck. Former internee and Irish Volunteer, John Shields, described the ship as the ‘most inhuman method of dealing with state prisoners’ due to the overcrowding and unsanitary conditions. There were often up to 50 men interned in one cage, which measured 20 to 40 feet, resulting in conditions so ‘congested’ that there was little room for either tables or chairs. The latrines, positioned at either end of the deck, were regularly ‘stopped up’, which meant that the overflow often ran down by the cages.⁹ The food was of an ‘inferior quality’ and was reportedly condemned by both the ‘interned doctor’ and the governor of the prison ship A.D. Drysdale. The men, who were served blackened potatoes for dinner, were provided with a sparse quantity of bread, margarine and butter for breakfast. Knives, forks and enamel mugs were supplied to the internees, but various reports emerged that prisoners had to eat their food ‘while sitting on the floor’.

The internees had access to the upper deck for exercise during the hours from seven in the morning to eight in the evening. The exercise space, however, was overcrowded and covered with a wire enclosure to prevent internees jumping ship. Inside the cages, the sleeping arrangements were little better. Some internees were supplied with mattresses while others slept in swing hammocks. Appeals for additional clothing were not granted and, consequently, several men had to go ‘through the winter with wet feet’. In these circumstances, many men succumbed to serious bouts of illness. Scabies broke out, and a lice infestation spread because of the lack of proper laundry facilities for clothes and bed linen. As a result of the spread of head and body lice, several prisoners had to be removed to isolation cells in Belfast prison. The atmosphere on the ship was most unhealthy; cases of tuberculosis and flu were reported among the prisoners.¹⁰

As early as October 1922 Dawson Bates conceded that ‘the accommodation on the Argenta was not sufficient for purpose’. Nevertheless, these conditions persisted into 1923, and until the internees were finally removed from the ship. In 1933 Bridget O Donnell was granted a military service pension on account of her late husband’s service during the conflict. Given Bridget’s description of her husband’s health, prior and subsequent to his incarceration, and in light of contemporary accounts of the HMS Argenta, it seems likely that his death resulted from the grossly substandard conditions on the ship. In later years, the former internee John Shields remarked that ‘it was a marvel the men survived so long under such living conditions’.The last remaining HMS Argenta internees were transferred to Belfast prison, Derry jail and Larne camp in January 1924.¹¹

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.