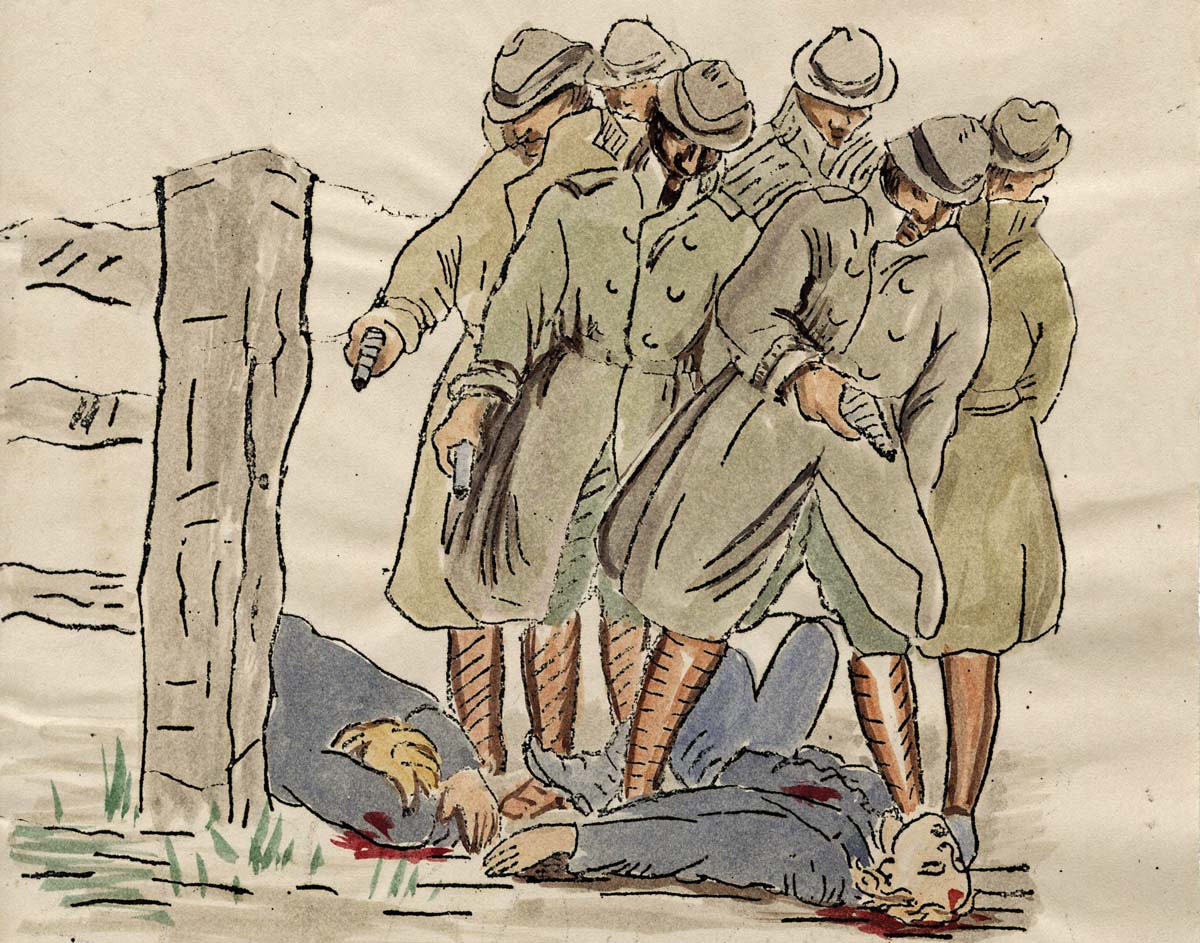

26 August 1922: The Killing of Seán Cole and Alf Colley

State Terror

By Brian Hanley

Dublin on Saturday, 26 August 1922 was a city in mourning. In City Hall thousands filed past the body of Michael Collins, killed just three days before. In Marino, to the north of the city centre, however, a group of young men had gathered to reorganise the anti-Treaty Fianna in the city. Twenty-one-year-old Alfred (Alf ) Colley had brought along two revolvers for instruction purposes. After the meeting, Colley, a tinsmith, and his nineteen-year-old comrade Seán Cole, who had just completed his electrical apprenticeship, walked home to the inner city together. At Newcomen Bridge near North Strand they were stopped at a checkpoint operated by men wearing a mix of National Army uniforms and plainclothes.¹ After a search the revolvers were found and witnesses saw the two men bundled into a Ford car and driven off. Their bodies were left dumped at the Yellow Lane, near Whitehall. Witnesses, including a British soldier, had seen them struggling with the men before being shot.²

On the same day, another republican, Bernard Daly, a grocer’s assistant, was also abducted, shot, and his dead body left in Malahide. The state forces denied any knowledge of these killings. Indeed, pro-Treaty sources suggested that the IRA had killed the men themselves. But suspicion began to fall upon a group of National Army Intelligence officers and members of the Criminal Investigation Department. Based at Wellington Barracks on the South Circular Road and Oriel House on Westland Row, these men were soon dubbed the ‘Murder Gang’ by republicans.

These were not the first cases of unarmed prisoners being killed by state forces. Harry Boland had been shot during his arrest in early August, while eighteen-year-old Joe Hudson was killed in a raid on his home on 10 August. In the month following the killings of Colley, Cole and Daly, four more IRA Volunteers died in dubious circumstances in Dublin. Two, Leo Murray and Rodney Murphy, were killed during a raid, but, it was alleged, after their surrender. In the cases of James Stephens and Michael Neville two weeks later, there was no suggestion of a gun battle. Stephens was taken from his lodgings in Gardiner Street and driven to the Naas Road, where he was shot and fatally wounded. Neville, a native of Clare, was picked up at the pub where he worked on Eden Quay and his body later found at a cemetery at Killester.

The killings established a pattern, discernible from over twenty deaths in the city during the war. Victims were abducted from their homes or workplaces and their bodies dumped in locations on the outskirts of the north or south side of the city. They sometimes bore the marks of ill-treatment. State forces denied any knowledge of the shootings and often sought to muddy the waters about the circumstances.

Controversial killings were not confined to Dublin. On 28 August Michael Danford, a Limerick IRA officer, was taken from his home by army officers and his body was found later on the Tipperary road. On the same day another Limerick IRA man, Harry Brazier, was shot dead by troops trying to arrest him at his workplace. In Cork on 8 September the body of Timothy Kenefick, an IRA member whose corpse bore signs of torture, was found. Witnesses described seeing troops arresting Kenefick earlier that day and the inquest returned a verdict of ‘wilful murder’. A week later, another IRA prisoner, James Buckley, was shot after seven soldiers had been killed in a mine attack.³ On 19 September Bertie Murphy, a labourer, was killed in custody in Killarney. Like Buckley, seventeen-year-old Murphy was shot in retaliation after two soldiers had died in an ambush. Some killings then, were unplanned and spur-of-the-moment reactions to the death of comrades. Those of Kenefick and Buckley, however, shared something in common with the deaths of Cole and Colley. The National Army commander in Cork, General Emmet Dalton, confirmed to Headquarters that members of Michael Collins’s elite ‘Squad’ were responsible for them. Dalton made clear that he approved of their actions, but many of his men did not, and troops in Cork threatened to mutiny unless the Dubliners were withdrawn.⁴

The ‘Murder Gang’ was largely (though not entirely)

composed of men who had been central to the IRA’s campaign

in Dublin prior to the truce. John Dorney has offered the best

analysis of this group.⁵ They were intensely loyal to Michael Collins and this, over

any other factor, had guaranteed their support for the Treaty.

After Collins’s death they were overwhelmed with a desire

for revenge, but also robbed of the one leader who could control

them. They usually killed in retaliation for the

loss of close comrades, and they had long memories. In June 1922

two army officers were killed in an ambush in Dublin. Over a year

later anti-treatyite Noel Lemass was kidnapped, tortured and

killed in revenge.

The group often displayed contempt for the fighting record of their enemies; their targeting of young republicans may have been influenced by this. While the majority of IRA Volunteers in Dublin, after the Easter Rising at least, never engaged in armed action again, the ‘Squad’ had been fulltime activists, constantly on the run and living on the edge. There is no doubt some of them were brutalised by the experience. Prior to the civil war many of the group had already gained a reputation for heavy drinking and erratic behaviour. But they were a vital factor in holding Dublin during the fighting in June 1922. Though republicans often pointed to the presence of former British servicemen in the state forces, the worst outrages against them were carried out by men with impeccable IRA records. The Squad’s former commander, Paddy O’Daly, who had led from the front in the IRA’s campaign in Dublin, was responsible for several brutal atrocities in Kerry. Though much of this violence was not formally authorised, it served a purpose for the state, augmenting the policy of official executions.

Those in government were certainly aware of the ‘Murder Gang’s’activities. Members of W.T. Cosgrave’s personal escort arrested Bobby Bonfield at Stephen’s Green in March 1923. Cosgrave was present when Bonfield, a UCD student, was taken away after a struggle. The IRA man’s body was found at Clondalkin a few hours later.⁶ (Bonfield was strongly suspected of involvement in the killing of pro-Treaty politician Seamus O’Dwyer in December 1922.) The Free State leader had himself suggested in February 1923 that, if in order to survive, the state has ‘to exterminate 10,000 republicans then the 3 millions of our people are bigger than the ten thousand’.⁷ So, while the civil war took place, those engaged in these activities faced little prospect of sanction. Indeed, the involvement of the Army’s Director of Intelligence, Michael J. Costello, in the last such killing, of military policeman and IRA informant Joe Bergin in December 1923, was covered up.⁸ There came a time when these activities were no longer tolerable, and many of the ‘Murder Gang’ would ultimately attempt to challenge the state themselves during the abortive ‘Army Mutiny’ of March 1924. Terror, official and unofficial, played an important role in the victory of the Irish Free State over its republican enemies.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.