25 May 1922: The First Anniversary of the Burning of the Custom House

Wearing The Green: Uniforms, Collectivity, And Authority

by Lisa Godson

On Thursday, 25 May 1922 the first anniversary of the IRA’s ‘taking’ of the Custom House was marked in Dublin. As the headquarters of the Local Government Board of Ireland, it had been of vital importance to the British administration before being attacked and burned by more than 100 young republicans dressed in civilian clothing; the necessary disguise to launch a surprise assault. The ensuing skirmish resulted in the deaths of five combatants and three civilians and the almost total destruction of James Gandon’s ‘jewel of Irish architecture’.¹ One year later, An t-Óglách reported the commemoration by ‘thousands of Irish soldiers’ who attended Requiem Masses with full military honours ‘for those of their comrades who lost their lives in this, the last big engagement of the Liberation War’.

Headed by a kilted pipers’ band, uniformed soldiers with rifles and fixed bayonets paraded through the streets to St Agatha’s church in North William Street, where a large tricolour, accompanied by a list of the names of some of the fallen, was carried to the altar. At the Consecration, military drum-rolls were sounded, and the royal salute was made to the Host. After the Last Post was played at St Agatha’s, the soldiers, joined by others, marched to the Pro-Cathedral for a second Mass, and then in procession to the ruined Custom House. The day’s ceremonies culminated there in a recitation of the Rosary in Irish for the repose of the dead. It was asserted in An t-Óglách that, except for Irish Volunteers’ attendance at Mass on the St Patrick’s Day before the Easter Rising, ‘this was the first occasion upon which the soldiers of an Irish Army were present at a Church function in Dublin’.² Of course, the majority of those soldiers had been present at countless church functions before. What the author meant was that this was the first time Irish soldiers attended a religious event together as soldiers. That is to say they were at Mass en masse in uniform, in formation, carrying weapons, sounding pipes and drums. But most importantly, they were in uniform.

The public collation of religious and military ceremony was one aspect of the statecraft of the Provisional Government. This was not actually the first time the army had attended a religious function: in March 1922 troops from Beggars Bush barracks paraded to a special Mass in the Pro-Cathedral, initiating a tradition of troops parading to Mass every Sunday.³ On St Patrick’s Day that year, the flag of the Irish army was publicly blessed at a special ceremony, with that fusion of Church and state represented in Sir John Lavery’s 1922 painting ‘Blessing of the colours’, which depicts the archbishop of Dublin blessing a tricolour held aloft by a kneeling soldier in Irish Free State uniform. Indeed, religious ceremonies, and in particular the Requiem Mass, became a key commemorative mode in the early years of the Free State, with the potentially divisive commemoration of Easter 1916 taking the official form of an invitation-only Mass at Arbour Hill under the Cumann na nGaedheal government and presided over by the National Army, whose members were described at the ceremony in 1923 as ‘clad in the uniform the men they honoured had sanctified with their blood’.⁴

25 May 1922— National Army soldiers kneel in prayer outside Dublin’s Pro-Cathedral during the Requiem Mass marking the first anniversary of the burning of the Custom House (Image: Topical Press Agency/Stringer; © Getty Images)

The issue of uniform and combatant clothing throughout this period in Irish history is complex and intriguing, reflecting the presence of many different armed factions and forces, the claims to identity conferred by a formal uniform, and the exigencies of guerrilla warfare that concealed civilian-clad rebels in a Dublin crowd, or clothed others on the run in trench-coats and broad hats. Those soldiers at the Custom House commemoration were in the new National Army uniform, first worn on the streets in early 1922 in limited edition by the Dublin Guard on a photogenic cross-city parade to receive Beggars Bush barracks from the departing British troops, and then issued unevenly in subsequent months. Its design was broadly based on the official dress of the Irish Volunteers, but in a green whipcord (for officers) or scratchy dark green serge (other ranks) rather than the grey-green described by Éamonn Ceannt in the Irish Volunteer in 1914 as appropriate in ‘a land where the prevailing tints vary from the grey of morning and evening twilight to the verdant green of midday’.⁵ Long established national symbols were retained from the Volunteers for the new uniforms, and still appear on those of the Irish Defence Forces a century later. The buttons were cast with a harp and ‘IV’ for Irish Volunteers; a cap badge, designed by Eoin MacNeill, featured ‘FF’ for Fianna Fáil (generally translated as ‘soldiers of destiny’, but a literal reference to the legendary Fianna band of warriors) within an eight-pointed star set against a sunburst, described in later regulations as the Gal Gréine derived from the Fianna banner. By means of such elements, the authority of the force on show in May 1922 was invoked through their connection with the historical Volunteers, and beyond them to a mythic Irish past.

As well as protecting the body, uniform functions to ‘promote internal discipline, convey hierarchy and status, legitimise violence and demonstrate the access the military force has to the means of production’.⁶

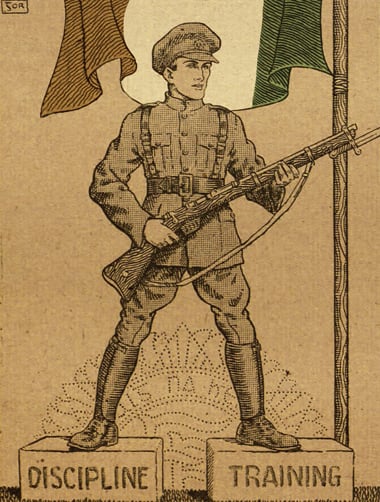

An illustration from An tÓglach (‘official organ of the Irish Volunteers’) associating the uniformed soldier with discipline and training (Image: An tÓglach, 24 June 1922; courtesy of Military Archives)

Most fundamentally, uniform visualises and shapes collectivity. In May 1922 such ideals might have been signalled by the sight of uniformed soldiers marching in formation, attending Mass and remembering ‘their’ heroic dead. The reality, however, was less comfortable. There was disquiet about the perception that the army lacked discipline, with post-truce recruits (or ‘trucileers’) being particularly disdained; there was internal squabbling about rank; and the supply of uniform remained difficult. This would come to the fore in subsequent months, when the National Army expanded rapidly to contest the civil war and acquired ex-British army uniforms to dye green. Adding further complexity, when asked to respond to rumours about the source of the uniforms in November 1922, the Quartermaster General’s office confirmed that ‘an order for 10,000 uniforms, greatcoats and slacks had been placed in England with Messers The Briscoe Importing Co.’,⁷ a Jewish-owned Dublin firm run by the brother of Robert Briscoe. An IRA member who was involved in importing arms for the anti-Treaty IRA, Robert was suspected of profiteering due to those family connections.⁸

Above all, of course, the split over the Treaty meant division rather than collectivity was to the fore, undermining the idea of a seamless continuity between the fallen comrades and those who publicly mourned them.The de Valera–Collins pact of 20 May, enabling the pro- and anti-Treaty sides in Sinn Féin to contest the June general election jointly, had led to reports expressing hope that the different factions might be reconciled, but for now many of the pre-Treaty combatants rejected the Irish Free State and its uniform. Reporting from the Four Courts a few weeks later, the journalist Clare Sheridan noted that the occupants ‘had no uniforms, but were heavily armed. Cartridge belts over serge suits seemed the dominant note’.⁹ Fractured allegiances, as well as different forms of combat, could mean rapid sartorial change, from Volunteer uniform in 1916, trench coats and hats during the War of Independence, Irish Free State army uniform in early 1922, ‘and then back again into trench coats and “broad black brimmers” when the Civil War broke out’.¹⁰ Just one month after the ceremonies at the Custom House, National Army troops would start the bombardment of the Four Courts, and Gandon’s other riverine jewel would be ablaze.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.