25 January 1922: Premiere of Swan Hennessy’s Second String Quartet, Paris

Art Music and the Struggle for Independence

By Harry White

‘In my early Dublin days’, the English composer (and Master of the King’s Music) Arnold Bax wrote in 1952, ‘I moved in an almost wholly literary circle. There was no talk of music whatever’.¹ I have always taken this comment (as have many other people) as a byword for the general apathy and indifference surrounding art music in Ireland in the years leading up to the foundation of the state. Bax’s own enchantment with Irish culture was mediated through his profound admiration for Yeats: in the shadow of Yeats’s poetry and plays, the temple of his own art was raised. His early tone poems are orchestral works inspired not by traditional music (he disdained the arrangement of Irish melodies by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, whose music, according to Bax, ‘never penetrated to within a thousand miles of the Hidden Ireland’), but by a visionary romanticism that lay on the cusp of political awareness.² Bax lived continuously in Dublin from 1911 until the outbreak of the Great War. On one occasion he invited Patrick Pearse to his home (in Rathgar) through the agency of their mutual friends, Padraic and Molly Colum. Bax was deeply impressed with his ‘death-aspiring’ guest, and recounts that when later he read the first reports of the Easter Rising (by the shore of Lake Windermere), he said to himself, ‘I know that Pearse is in this!’³ On 9 October 1916 he completed the short score of an orchestral work, entitled In memoriam and dedicated to the memory of Pearse; it lay unperformed until 1998. The original short score was presented to Éamon de Valera by Harriet Cohen in 1955, and subsequently deposited in the library of University College Dublin.⁴

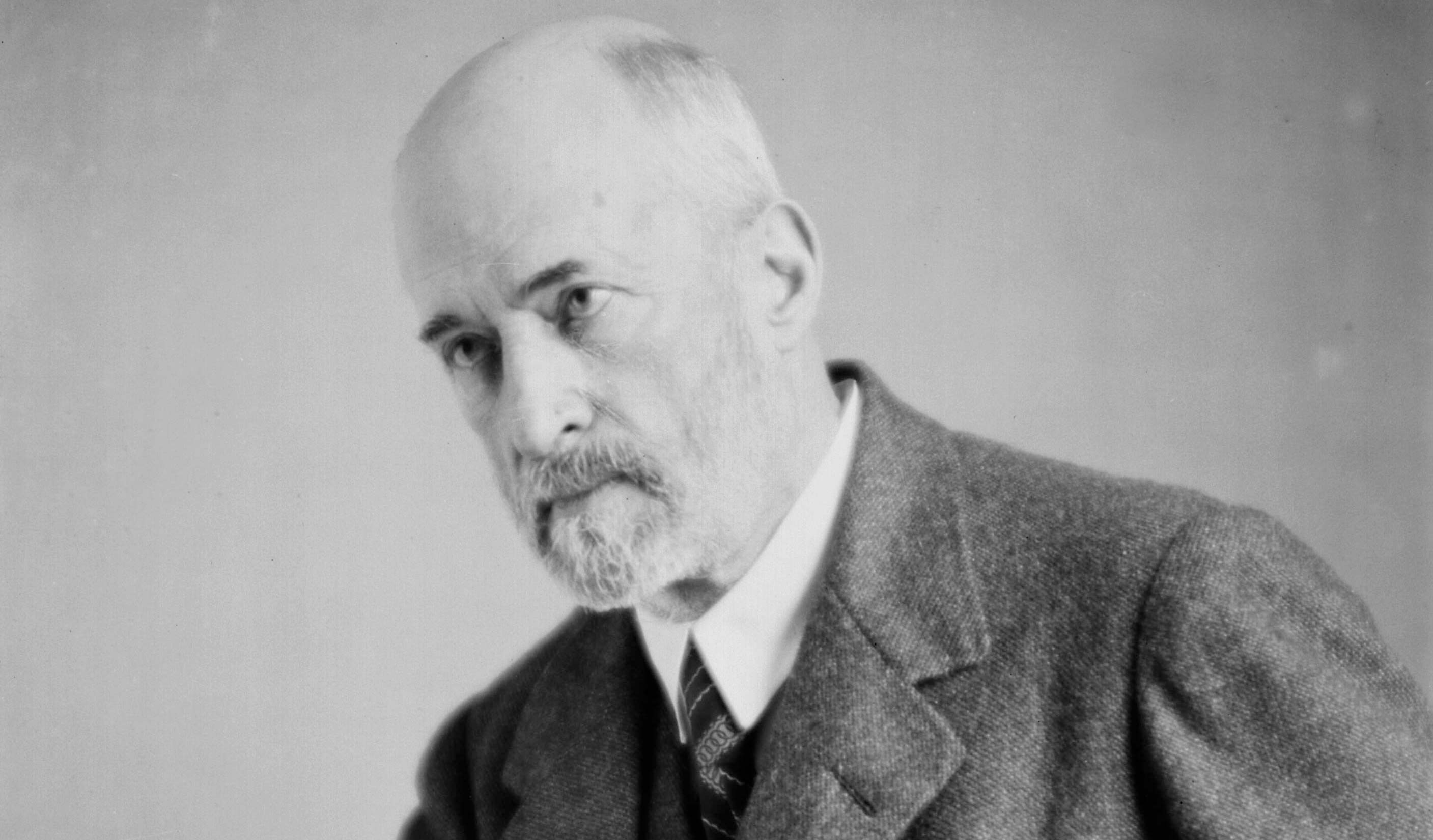

Until the publication in 2019 of Axel Klein’s Bird of time, a biography of the Irish American composer Swan Hennessy (1866–1929), Bax’s commemoration of Pearse had stood alone in the annals of Irish musical history on two counts, one of which endures. It was and remains the first musical work of art to memorialise a leading figure in Irish revolutionary politics by a (then) contemporary composer. Thanks to Axel Klein’s research, however, the solitary estate of Bax’s work (to say little of its long neglect) has been significantly modified by the rediscovery of a string quartet (opus 49) by Swan Hennessy written in memory of Terence MacSwiney, shortly after MacSwiney’s death on hunger strike in 1920. And whereas Bax’s commemoration of Pearse was either set aside or suppressed (we cannot really be sure), Hennessy’s string quartet was premiered by four Dublin-based musicians at the World Congress of the Irish Race in Paris on the evening of 25 January 1922. The audience at this first performance included de Valera, Countess Markievicz and Mary MacSwiney (sister of Terence), all prominent opponents of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.⁵

Given that a primary objective of the Irish Race Congress, organised prior to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, had been to promote support for the international recognition of the Irish Republic, it is not mistaken to argue that Hennessy’s quartet was at least implicitly sympathetic to the anti-Treaty delegation (led by de Valera). But the work’s immediate reception eclipsed the bitter identity politics that soon afterwards would herald the Irish civil war, in favour of its programmatic engagement with MacSwiney’s life, political struggle and death. In Bird of time, Axel Klein cites reviews of the premiere by the Paris correspondent of the New York Herald and of the Dublin premiere (a week later) in The Irish Times in support of this reading, together with an acknowledgement of the ebullient optimism of the work’s finale. Hennessy’s quartet mourned MacSwiney’s death and yet hoped for a better outcome.

|

|

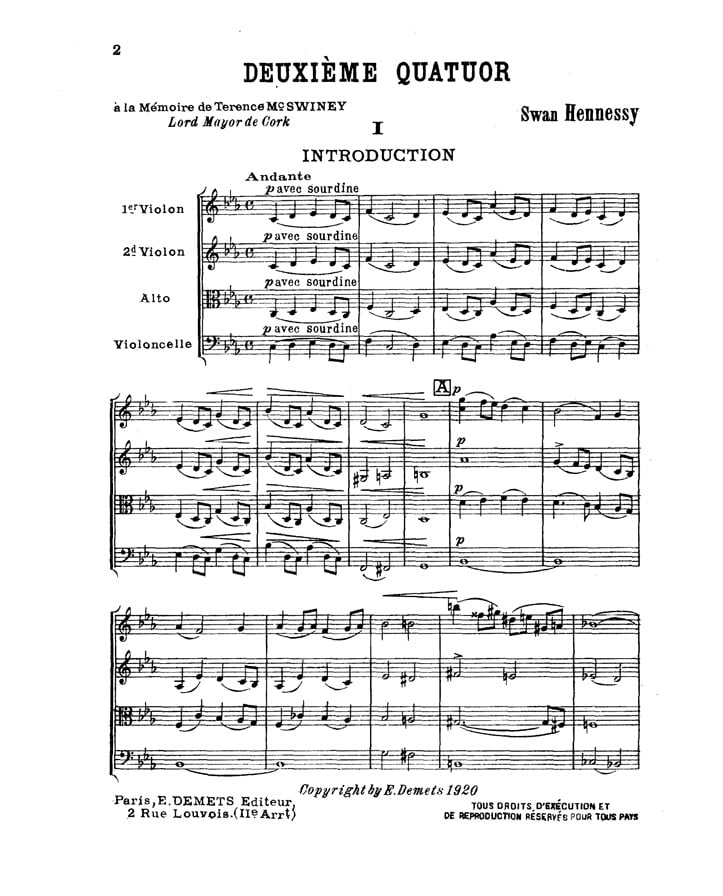

The cover (L) and first page of the score of Swan Hennessy’s Second String Quartet, op. 49 (Paris, 1920), with dedication to the memory of Terence MacSwiney. To view the full score as a PDF, click here. (Image: International Music Score Library Project (Petrucci Music Library); public domain.

In Dublin, Paris and (shortly afterwards) Berlin, Hennessy’s music was immediately intelligible as an inherently and ineluctably Irish work of art, whatever the nationality of its composer. Klein documents twelve concert performances of the quartet between 1922 and 1939, in addition to two radio broadcasts.⁶ Thereafter, it lapsed into long silence. It would not be heard again until the work was revived by the RTÉ ConTempo Quartet (at the instigation of Axel Klein) in 2016. A recording of Hennessy’s complete string quartets by the same ensemble would follow in 2019.

How does one account for this mute afterlife? How can one reinscribe a work such as Hennessy’s opus 49 into the cultural narrative that ensues upon the commemoration of 1922 represented by the present publication? The centenary itself prompts an answer. So too does Yeats’s prestige, and that of the literary revival he fomented. If we think of works of art in relation to the upheavals of the era, we think perhaps first and foremost of ‘Easter 1916’ (completed within a month of Bax’s In memoriam in September 1916, and published in 1921 within a year of the composition of Hennessy’s string quartet). We may also think of 1922 as the annus mirabilis of European literary modernism, given that Joyce’s Ulysses was published that year (in Paris), to say little of Eliot’s The waste land. We are unlikely to think of Hennessy’s string quartet, however, as anything other than a pièce d’occasion, now faded within the folds of a largely forgotten cultural history. Even if this appears to do scant justice to Hennessy, who lived in Paris from 1903 until his death in 1929 and whose work is constantly imbued with an awareness of his Irish musical heritage (his father was an Irish emigrant to the United States), it remains nevertheless true that there was little or no contextual affordance by which this work might belong to an Irish musical soundscape. As late as 1937, an Irish civil servant could characterise art music as a ‘Victorian form of educational recreation’, fundamentally irrelevant to the young state’s artistic ambitions. To borrow a phrase from Klein, modern Ireland was ‘no state for music’.⁷

Klein means ‘art music’, or ‘contemporary classical music’, a distinction that gains in importance when we consider how assiduously (by contrast) the new state sought to recuperate its ethnic musical inheritances. ‘The more we foster modern music, the more we help to silence our own’, Richard Henebry, a passionate ideologue of cultural chauvinism, had written in 1903.⁸ This was long in advance of the general silence and neglect that would rapidly envelop the enterprise of art music as an indigenous preoccupation in the Ireland of the 1920s. For decades, Irish art music would remain an ‘invisible art’, and an inaudible one. A century after partition, this remains largely the case. Most of Bax’s Irish tone poems have very rarely (if ever) been heard in live performance in Ireland, and the same is true for the greater part of Stanford’s oeuvre. Almost a century after independence, the greater part of Ireland’s art music estate remains shrouded in silence.⁹

And yet: as Axel Klein has shown, the implacable record of this estate suggests otherwise. There is a history of Irish musical ideas deserving of our attention, notwithstanding the complacency (and worse) of a cultural and educational matrix that regards ‘classical music’ as a bewildering antagonism to the Irish story. To recover Swan Hennessy’s serenely achieved meditations on Terence MacSwiney in 1920, destined as these originally were in 1922 for an audience in the throes of state formation, is an enterprise which deepens rather than diminishes our reception of Irish history over the past century.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.