25 February 1922: Publication of the ‘Free State’ Newspaper

The Propaganda War Over the Anglo-Irish Treaty

By Ciara Meehan

Before the physical fighting of the civil war began, a propaganda war was fought by those divided over the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Both sides turned to newspaper publishing to make their case. An Saorstát: the Free State, referred to simply as Free State by contemporaries, first appeared on 25 February 1922. It served as a voice for those who endorsed the agreement before an official pro-Treaty party, which would become Cumann na nGaedheal, was formed. Appearing weekly, thirty-nine issues of the eight-page newspaper were published. It was filled with lengthy articles, interspersed with satire. Although official circulation figures are not available, other evidence suggests that the paper did not have a great reach. Nonetheless, Free State offers the historian further insight into how the pro-treatyites sought to present their case in the weeks and months after the Dáil voted to accept the agreement.

As the Dáil debates drew to a conclusion, the anti-Treaty side moved quickly to disseminate its case to the broader public. The newspaper Poblacht na hÉireann: the Republic of Ireland, or Republic, was launched at the start of January 1922. From February, Erskine Childers directed a vigorous propaganda campaign in its pages, seeking to emphasise that the Dáil was powerless to function as a parliament. This was intended to undermine the process of transferring power, including the civil service structure, from the British government to the new Irish Free State.¹

Free State was conceived in late January amidst concerns about the influence of Republic. It sold for two pence, but free bundles were also dispersed around the country for distribution at public meetings. Though the majority of articles did not carry a by-line, Ernest Blythe, Darrell Figgis, Eoin MacNeill, Kevin O’Higgins and Kevin O’Shiel were among those who signed their names to their occasional contributions. When read consecutively, the columns start to feel like repackaged versions of earlier editions. The ‘sameness’ of the content can be explained by the recorded difficulties in securing copy.² Advertisements broke up some of the text, but the revenue generated from them made only a minimal contribution to the coffers. That they were mainly for luxury goods was an early sign that the pro-Treaty organisation would have little appeal for the working class.

A lengthy discussion of the Treaty occupied the front page of the inaugural edition. Echoing the Dáil debates, the choice was presented as one between accepting the terms of the agreement or the ‘resumption of war or political chaos’. The latter, readers were told, would leave them further than ever from the realisation of their hopes—an inverted version of Michael Collins’s claim that the Treaty would provide the freedom to achieve full freedom. Another article in the same issue positioned the Treaty in the longer republican tradition. Summoning Robert Emmet, it claimed that ‘Ireland again takes her place amongst the recognised Nations’.³

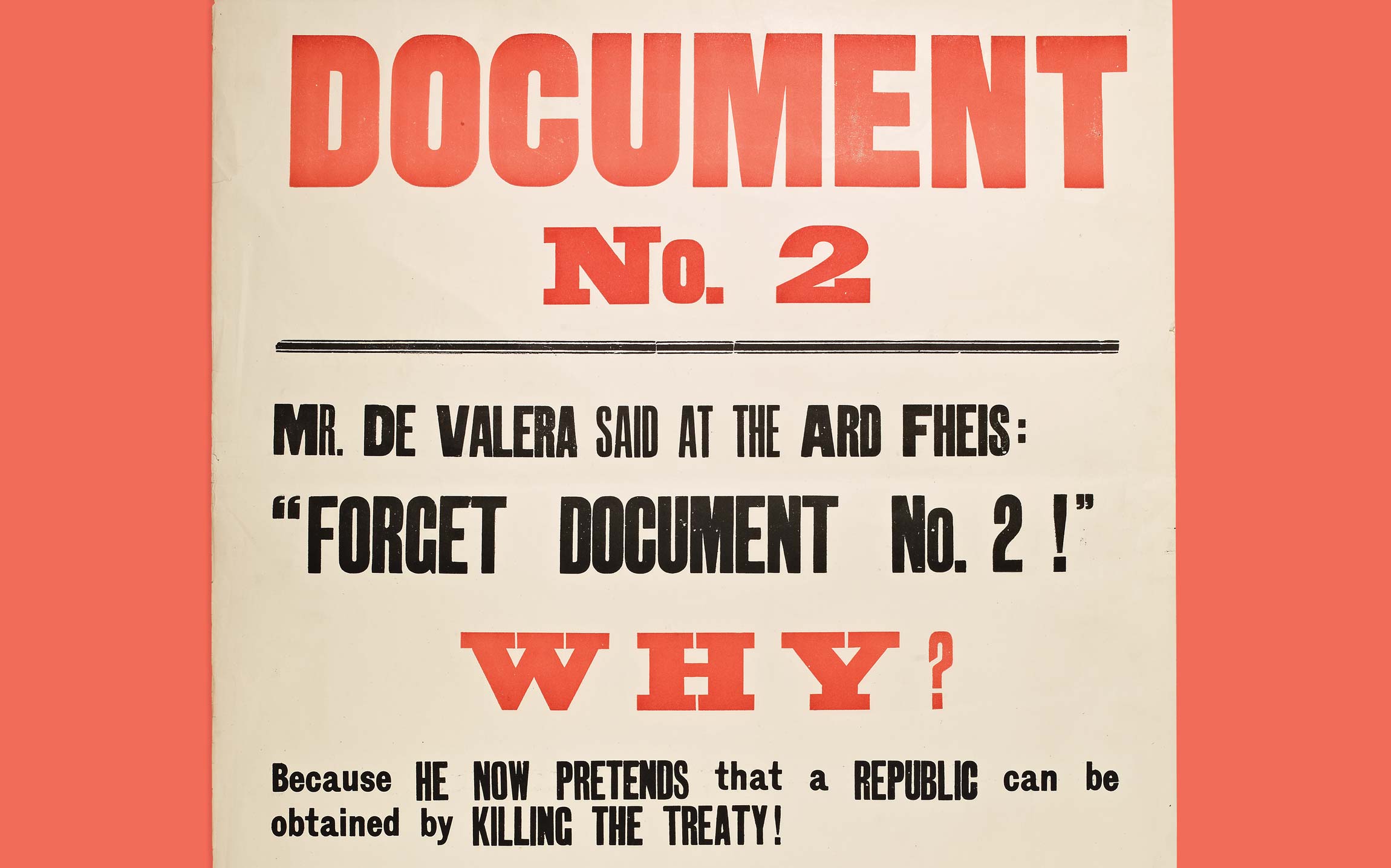

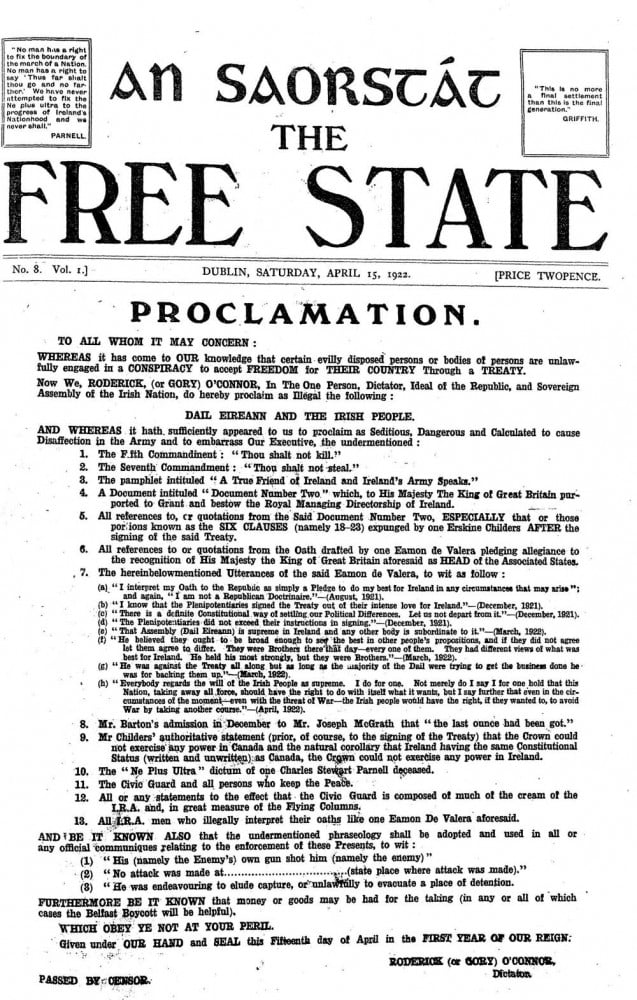

‘Legitimacy’ was a recurring feature of the political lexicon in the months that followed the vote on the Treaty.⁴ De Valera’s ‘Document No. 2’ was repeatedly scrutinised in Free State, and its perceived shortcomings, relative to the Treaty, were highlighted. As the threat of violence hung in the air, there was occasional scaremongering, mostly in the shape of vague warnings that discontent could lead to the return of British rule. On 15 April, the day after anti-Treaty forces led by Rory O’Connor occupied the Four Courts, a satirical ‘proclamation of lawlessness’, signed by ‘Roderick (or Gory) O’Connor. Dictator’, appeared on the front page. Much of that issue was taken up with discussions of despotism—a dominant theme in the newspaper from its inception, though earlier references tended to relate to Éamon de Valera.

|

|

Two front pages from An Saorstát: the Free State. The one of the left is from 15 April 1922 and the one on the right, the Michael Collins Memorial number is from 30 August 1922. Click images to enlarge.

When Collins and de Valera agreed a pact for the 1922 election intended to avert civil war, a pro-Treaty sub-committee agreed that all propaganda would be suspended from 23 May.⁵ While subsequent Free State articles were more muted, elements of the pro-Treaty narrative lingered. A recurring advertisement for the Treaty fund asked, ‘Where does your interest lie? In good government or in gun-law?’⁶

In the aftermath of the election, and the failure of the pact, the Provisional Government issued an ultimatum to the anti-Treaty forces to withdraw from the Four Courts. After they refused to do so, the Free State army bombarded the complex on 28 June and the civil war began. The next nine issues of Free State were branded ‘special war numbers’. They justified the attack and further vilified those who opposed the Treaty.

These special editions were disrupted by the killing of Michael Collins, resulting in the publication of a ‘memorial number’ on 30 August. The newspaper then reverted to its usual format. Although the civil war continued, references to war were dropped from the banner. As the newspaper went to print at the start of September, the third Dáil was days away from convening for the first time. The purpose then was to add legitimacy to the new parliament. By the time Free State ceased production in November, the Dáil had been convened; W.T. Cosgrave was elected president of the Executive Council; and the new constitution was adopted. The process of implementing the Treaty was nearing its conclusion. Discussions were also underway about the formation of a pro-Treaty party.⁷ These developments alone, however, do not explain the newspaper’s demise.

Minutes of the Free State sub-committee repeatedly record maladministration by its manager, Lyons. While the precise identity of the manager is not clear, it is likely that the Lyons in question was George A. Lyons, a friend of Arthur Griffith’s who was active in the independence movement. Among his failings were incomplete financial records for the paper and an absence of any details about circulation figures—an essential piece of information if one of the expectations was that the newspaper would counteract its rival. A decision had been taken at the start of April that, if his performance did not improve, ‘drastic action would be taken’.⁸

Lyons ultimately resigned, but the newspaper’s future remained uncertain. Its continued existence was championed in June by Arthur Griffith, whose long career as editor of various newspapers demonstrated his belief in the power of that medium. His intervention gave Free State only a temporary stay, however, and the 11 November edition was its last. By then circulation had dropped so substantially that the newspaper was deemed to have lost all propaganda value.⁹ Although the pro-Treaty side saw the usefulness of a newspaper, Cumann na nGaedheal did not launch a new publication after its creation (as Fianna Fáil later would with the Irish Press). That the national newspapers and the majority of the provincial press were sympathetic to W.T. Cosgrave’s government negated the need.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.