22 December 1922: Patrick Hogan’s Memorandum on Land Seizures

‘Agrarian Anarchy’: Containing the Land War

By Heather Laird

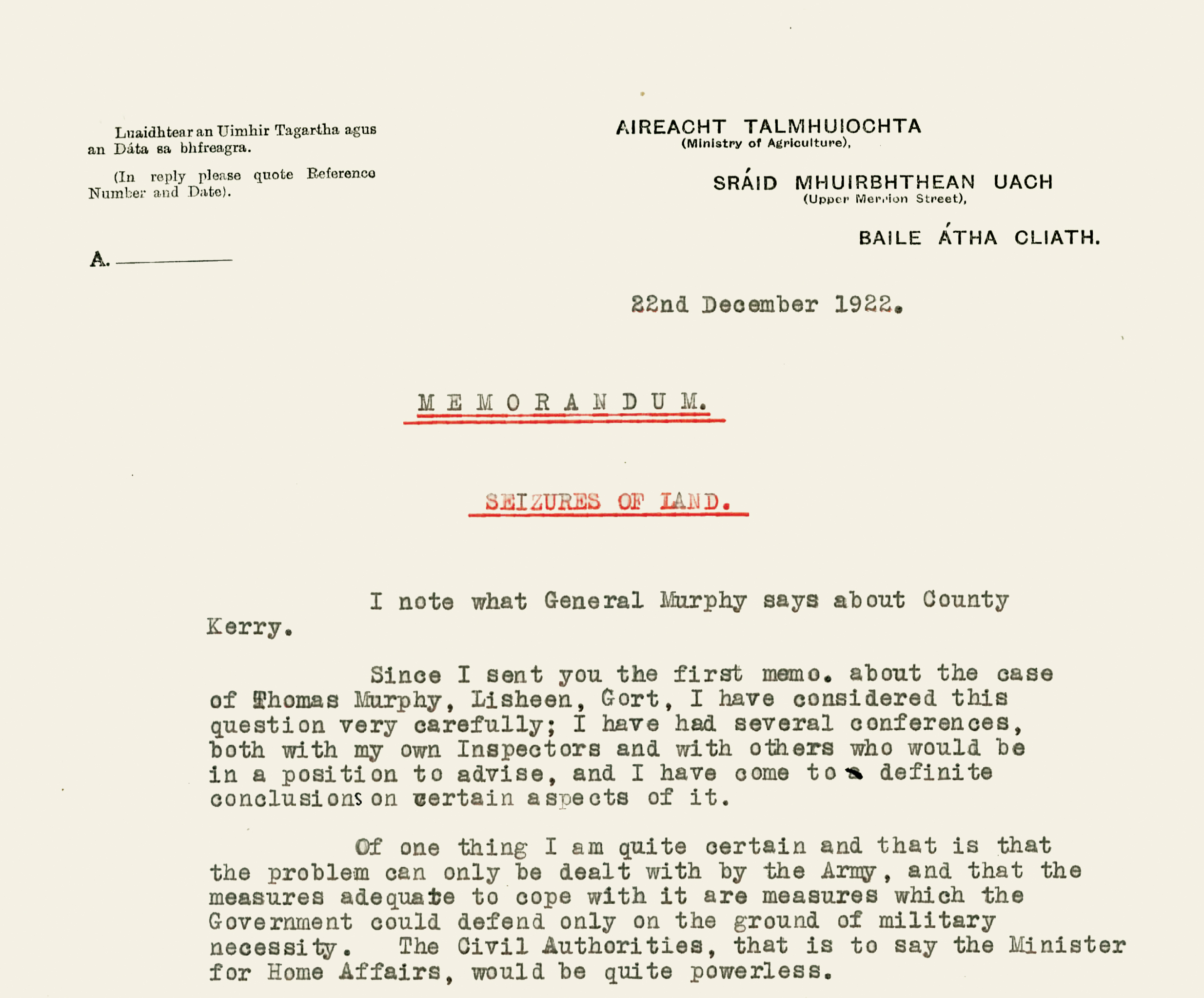

On 22 December 1922 Patrick Hogan, minister for agriculture in the Irish Free State government, sent a Cabinet memorandum on ‘seizures of land’ to William Cosgrave, president of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, Kevin O’Higgins, minister for home affairs, and Richard Mulcahy, minister for defence. Six days later the memorandum was again sent to Mulcahy, this time from the president’s office, with an accompanying letter stating that the president ‘thinks this matter is of importance ’.¹ The content of this memorandum, in particular the assertion that the ‘Land War is very widespread and very serious’, may surprise those who associate agrarian unrest in Ireland with the late nineteenth century and who assume that the Irish land question had by this point in time been answered by land purchase acts such as the Wyndham Act of 1903.² As indicated by Hogan’s mem- orandum, however, outbreaks of land agitation occurred in Ireland well after the events of 1879−82 that are generally termed the land war. These outbreaks included the period leading up to and following the sending of this memorandum.

In the spring and early summer of 1920 rural unrest was particularly pronounced, with officially returned ‘agrarian outrages’ higher than in any other year since 1882, but there was also notable unrest during the civil war. The dominant form that rural agitation took in the early 1920s was the seizure of land. Land let out to graziers on the eleven-month system and land under the control of the Congested Districts Board was especially targeted,³ though even the farms of small and middling farmers were not guaranteed to be safe. Some seized land was broken up into holdings for individual farmers, non-inheriting farmers’ sons or landless labourers, and some was turned into commons, occasionally referred to as ‘Soviets’. A one-thousand-acre farm in County Clare belonging to H.V. McNamara, which was seized and used collectively by at least 37 small farmers and fish- ermen, is an example of one such commons. An immediate context for such land seizures was escalating tensions over resources because of the impact of the First World War on emigration and on beef prices. In the west of the country in particular, an already chronic land hunger that ‘peasant pro- prietorship’ of itself could not alleviate was exacerbated by restrictions on emigration; furthermore, increased beef prices ensured that land was more likely to be let out for commercial grazing than subsistence farming.

Hogan’s memorandum points to a tense relationship between agrarian agitators and mainstream nationalists. In the west, land congestion had created a dissatisfaction that provided much of the energy for the War of Independence, but there was a relatively low participation in that part of the country in the war. For many within the nationalist movement, the land issue was not only a distraction from the national project but threatened to derail it. Hence direct action aimed at land redistribution was a source of consider- able anxiety for both the first Dáil and the Free State government. Land was also a factor in the civil war conflict. Rural discontent was viewed by such opponents of the Treaty as Liam Mellows as a means of mobilising anti- government support, while key members of the government were hostile to an agitation that they believed was being used to undermine the authority of the Free State. Thus, a connection was made between land seizures and anti-Treaty ‘irregularism’, and a corresponding link formed between the defence of private property rights and the defence of the fledgling state.

Attempts to contain agrarian unrest in the early 1920s included the estab- lishment of special land courts and of a land commission by the first Dáil, and the introduction by the Free State government of a 1923 land bill focused on redistributive land reform. Coercive measures were also employed. Most notably, the Special Infantry Corps was set up just over a month after Hogan claimed in his memorandum that ‘it is quite impossible ’ to deal with the seizing of land ‘as an ordinary criminal matter’.⁴ Kevin O’Higgins informed an army inquiry committee in 1924 that the corps was formed as a direct result of the memorandum and ‘did effective, if “rough and ready” work in stamping out agrarian anarchy and other serious abuses existing and arising at that time’.⁵ In 1923 the corps arrested at least 173 people for ‘agrarian offences’.⁶ Reasons recorded for arrest include ‘interfering with land other than his own’, ‘breaking down walls’, ‘unlawful grazing’, ‘illegal tillage’ and ‘unlawful possession’.⁷ More commonly, the corps simply cleared seized land. Those who established the illegal commonage on McNamara’s estate in Clare were initially evicted by the Special Infantry Corps in July 1923. Following reoccupations of the land, they were again evicted in December 1923 and May 1924.⁸ Further coercive measures included the confiscation of stock, as took place in the case of the County Clare occupants in the December 1923 eviction; the debarring of those involved in seizures from future land distribution; and the paying of fines and compensation.

Notwithstanding the use of reform and coercion in the early 1920s to stem rural discontent, agrarian unrest continued to be a feature of Irish society, as evidenced by the anti-land annuities agitation that commenced in 1926, and activism associated with Clann na Talmhan in the late 1930s and early 1940s. As suggested here, land agitation is a more significant and sustained aspect of Ireland’s past than is generally acknowledged. One way the Irish state could mark its historical importance is to open up the untapped resource that is the Irish Land Commission archive and make its approximately eight million documents fully accessible to all who wish to study them.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.