21 January 1922: The Irish Race Congress

Global Ireland

By Darragh Gannon

On 21 January 1922 John Whelan arrived from Java for the Irish Race Congress in Paris. It was held between 21 and 28 January, and was an initiative of Irish nationalists in South Africa that sought to offset the power of the British empire during the War of Independence and Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations by mobilising the political and cultural influence of the global Irish diaspora. Over one hundred delegates from twenty-two countries would attend. Journeying over four weeks to be in attendance at the event, the single representative of the Dutch East Indies cut an isolated figure among the delegations representing Australia, Argentina and Great Britain. ‘You have a representative here from Java. It is absurd’, the London-based Art O’Brien commented: ‘the Irish colony of Java, I understand, consists of six or seven people, and they are not organised at all’.¹ Whelan’s presence at once illustrates the global scope, and great divergences, that characterised Irish nationalism during the revolution. The worldwide movement of Irish revolutionaries, transnational organisers and internationalist activists collectively signified the importance of political activism beyond Ireland’s borders. To what extent did the eventful year of 1922 mark a rupture in the global order of Irish nationalism? To assess the legacy of the civil war, we must locate revolutionary Ireland in its international historical context.

Ireland was a subject of global import in the aftermath of the First World War. Reports of the first meeting of Dáil Éireann in Dublin on 21 January 1919 travelled the world: ‘Irlanda y el Sinn-Feinismo’ (Mexico City); ‘Sinn Fein assembly, independence declared’ (Mumbai); ‘Demand English leave Ireland’ (Tokyo).² Terms such as ‘republic’, ‘self-determination’, and ‘small nations’ were immediately recognisable in this global ‘moment’. ‘The High Command of Fiume…now associates itself with the analogous declaration of the Irish Republic’, the Italian revolutionary Gabriele D’Annunzio informed the League of Nations.³

Without access to the immediate publicity offered by political representation at Westminster, securing international recognition of the republic, paradoxically, became integral to the politics of Sinn Féin. In early 1919, Versailles, not the Mansion House, was the centre of the Irish world. The Dáil’s premier diplomats Seán T. O’Kelly and George Gavan Duffy lobbied the world’s powers for entry to the Paris Peace Conference, while associating with internationalist activists such as Egypt’s Sa’d Zaghlul and Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh beyond its halls and mirrors. Neither the Irish Republic, nor its representatives, ultimately, would be admitted at Versailles. A network of envoys, press agents and cultural influencers would, however, represent the nascent Irish Republic across the continent thereafter: in Antwerp, Geneva, Rome, Stockholm. Irish nationalist women, notably, enjoyed considerable political status and responsibility in Europe; Nancy Wyse Power and Máire Ní Bhriain assumed publicity portfolios on behalf of Dáil Éireann in Berlin and Madrid respectively. Most significantly, Patrick McCartan journeyed to Moscow with a view to establishing diplomatic relations with Soviet Russia, drafting a provisional treaty between the two governments.

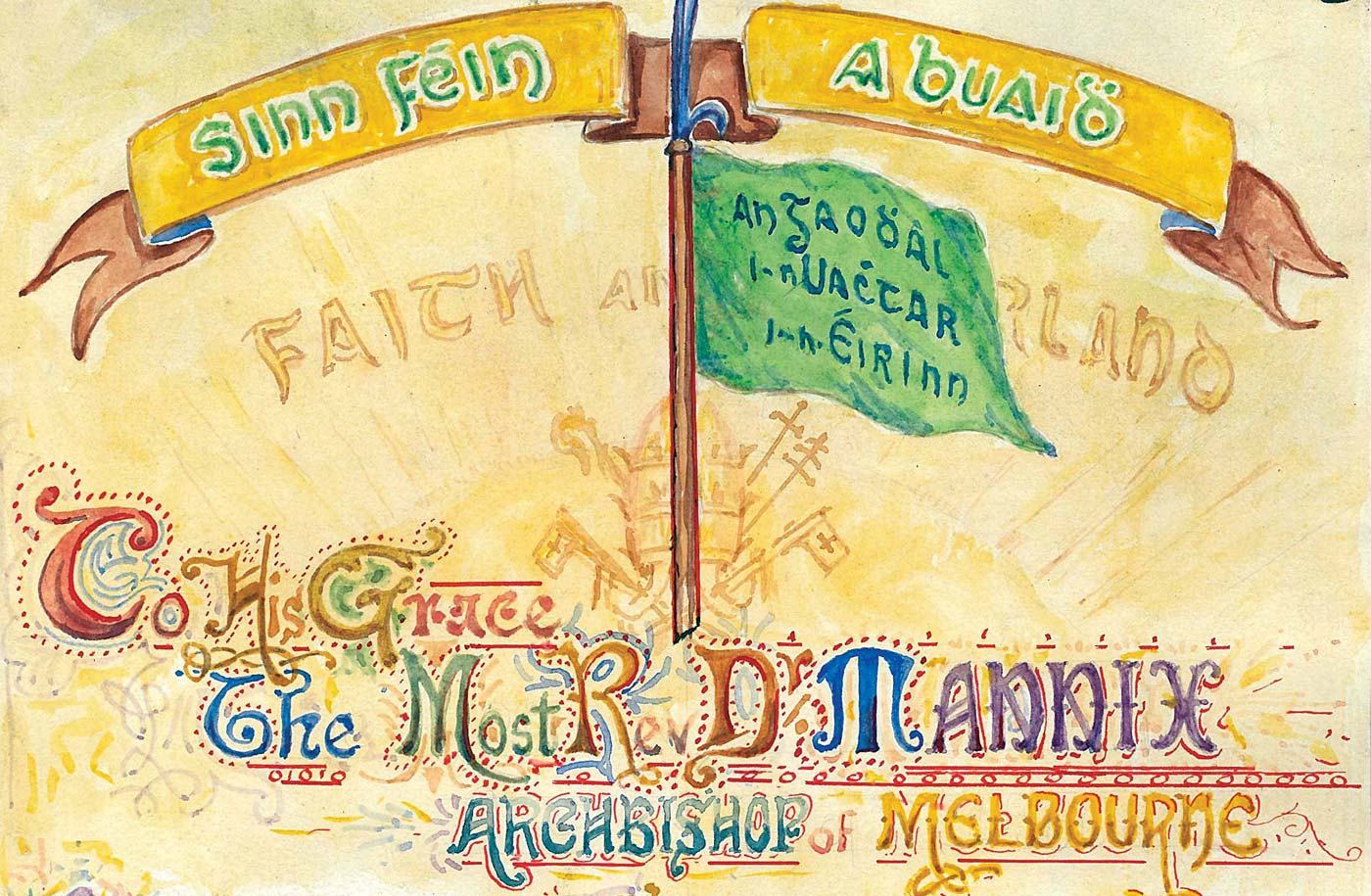

The international ambitions, and internationalist connections, of Irish nationalists had put the Irish Republic on the map in Europe. In a letter to Monsignor John Hagan at the Pontifical Irish College in Rome, Seán T. O’Kelly addressed a second strand of global Ireland: the Irish diaspora (a worldwide community often denoted in Irish-Catholic terms). ‘Our people would take all possible steps to have the Catholics of America, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa, and all the other places where the Irish have planted and maintained the Catholic Church, join them in a form of protestation to the Vatican.’⁴ The outspoken archbishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix, meanwhile, toured the United States in 1920 campaigning against British policy in Ireland. His later arrest off the coast of Cork further focused media attention in Australia and the United States on British rule in Ireland. In a meeting at the Vatican in May 1921, Mannix convinced Pope Benedict XV to issue a call for peace in Ireland, rather than the denunciation of the IRA demanded by British diplomats.

VIEW: The full version of the illuminated address presented to Archbishop Daniel Mannix in 1920

As the dominant power in the post-war world, and the largest centre of Irish settlement, the United States presented the most auspicious political space for recognition of the republic. The America-first politics of the New York-based Friends of Irish Freedom influenced the passing of resolutions in support of Irish self-determination in the US Senate. The failure to apply self-determination to Ireland, Woodrow Wilson confided to leading Irish Americans, had proven the ‘great metaphysical tragedy of today’.⁵ Éamon de Valera’s high-profile campaign across the United States between June 1919 and December 1920 attracted unprecedented financial support ($60 million in today’s money) on behalf of the republic. His island-centric politics, however, would imbalance the equation of Irish American nationalism, prompting a public split over his comparisons between Ireland and Cuba.⁶ To Daniel Cohalan, who presented the case for Irish self-determination at the Republican Party Convention, de Valera was ‘woefully out of touch with the spirit of the country’.⁷ While his Washington D.C.-based American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic failed, ultimately, to secure recognition from the US administration, de Valera’s campaign secured the freedom of speech of Irish nationalists, an increasing challenge for Dáil Éireann in Dublin.

Elsewhere, Irish nationalists were to co-ordinate their efforts across the British empire as part of the ‘self-determination league’ movement. Successive organisations were established in Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, forming what Dáil envoy Osmonde Grattan Esmonde described as ‘the complete framework of a world-wide race organisation’.⁸ Esmonde was one of many ‘global connectors’, individuals who propagated Ireland’s cause through their movement across borders and cultural boundaries. Departing New York in December 1920, he arrived in Auckland in March 1921, with a view to organising the self-determination league in New Zealand. Arrested one month later for issuing seditious speeches on the islands of Fiji, he was deported to Canada.

Other ‘global connectors’ mobilised support for the republic through Ireland’s diaspora communities. The Prince Edward Island-born journalist and activist Katherine Hughes successively established branches of the Self-Determination for Ireland League of Canada and Newfoundland; toured the ‘Deep South’ of the United States with Éamon de Valera; organised the Self-Determination League movement in Australia and New Zealand; and coordinated the arrival of Irish representatives from twenty-two countries for the Irish Race Congress in Paris. The transnational movement of individuals underpinned the political ideology of ‘global Ireland’.

Over the course of the Irish revolution, Irish nationalists around the world institutionalised the idea of ‘global Ireland’ through the organisation of successive Irish Race Conventions. Between 1919 and 1921, these events were convened in Philadelphia (1919), Melbourne (1919) and Buenos Aires (1921). The Irish Race Congress in Paris in January 1922, most impressively, was coordinated by nationalist organisers in London, Dublin, Toronto and Pretoria. ‘It is not the Ireland of four millions that we are thinking of now’, the South African-based leadership explained: ‘we are thinking also of the greater Ireland, the Magna Hibernia across the seas…they must not be, and they are not, wholly lost to Ireland’.⁹

Having been envisaged by its convenors as a means of invoking the global influence of the Irish diaspora during the Treaty negotiations, the Irish Race Congress would eventually descend into acrimony in the aftermath of the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921. Its one hundred delegates would be divided, not only on their views of the Treaty, but on their vision for a global Ireland. Differences of perspective between the Irish in South America and South Africa on issues of race, citizenship and nationality, much less the Treaty, would undermine the coherence of the projected global Ireland organisation: Fine Ghaedheal. The New York Times commented presciently of proceedings:

whether in Paris or Dublin or New York, sensible Irishmen must be aware that the final test of their capacity to govern themselves is now upon them…the only Irish Race Congress which the world will note, or long remember, is not the one in Paris but the one in Dublin.¹⁰

The Irish civil war altered the outlook of Irish nationalism, narrowing the focus of Irish revolutionaries from a global Ireland to a more island-centred politics, and diverting attention from the scale of republican international achievements to the minutiae of intra-national differences. A century of independent statehood and historical scholarship has reinforced the ‘ourselves alone’ narrative of the Irish revolution. The separation of the Irish diaspora from the historiography of the Irish revolution to date speaks to the ‘double marginalisation’ of the Irish migrant: from Irish society and from its historical record. Fine Gael has been written into the Irish history books as the twentieth-century political successor to the pro-Treaty party; ‘Fine Ghaedheal’, by contrast, has been consigned to the footnotes of Irish history, and the distant scholarship of diaspora Ireland. The worldwide movement of Irish nationalists is deserving of a historical legacy to remember. A century after the Irish Race Congress in Paris, the Irish state has, significantly, returned to the idea, and influence, of ‘global Ireland’.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.