2 March 1922: Countess Markievicz Defends Female Citizenship

‘Free State Freaks’: The Politics of Masculinity

By Aidan Beatty

On 2 March 1922 Constance Markievicz, by then a strongly anti-Treaty member of the Dáil, addressed her fellow TDs and, in a short but oddly bipartisan speech, urged them to support female suffrage in the new Ireland. Responding to an earlier statement by the pro-Treaty TD Joseph McGrath, who had condemned female anti-treatyites as ‘women in men’s clothing’, Markievicz offered an ample defence of women’s voting rights. Women, she said, had fully fought for national liberation and so had proven their right to be full citizens, or as she stated at the end of her brief remarks: ‘these young women and young girls…took a man’s part’ in the Anglo-Irish War.¹ This debate about voting rights slipped into a deeper debate about gender norms and the porous divide between ‘male’ and ‘female’ identities. This was, in fact, a recurring debate both in 1922 and later.

In 1924, two years after Markievicz’s speech, Patrick Sarsfield O’Hegarty published his seminal contemporary history, The victory of Sinn Féin. Intemperate and readable, the book ranged across the tumult of post-1916 Ireland with an unsurprisingly nationalistic tone and content. And when it came to discussing the civil war, O’Hegarty proffered an interesting theory as to the root causes of the split between treatyites and anti-treatyites. In a chapter entitled simply ‘Furies’, he argued that the wartime conditions prevailing in Ireland since 1914 had irreparably damaged the women of Ireland, ‘cutting [them] loose from everything which their sex contributes to civilisation and social order’. Nationalist women, members of Cumann na mBan most of all, had supposedly violated the gendered division of labour of Irish nationalist politics; these were the ‘Furies’ of O’Hegarty’s imagination. And he laid the blame for the civil war at the feet of the ‘Furies’ whose ‘hysterical’ dedication to republicanism served to fatally undermine the bond of brotherhood previously uniting the nationalist men of Ireland. ‘Left to himself, man is comparatively harmless’, O’Hegarty observed, but

it is woman…with her implacability, her bitterness, her hysteria, that makes a devil of him. The Suffragettes used to tell us that with women in political power there would be no more war. We know better now. We know that with women in political power there would be no more peace.²

Writing from the vantage point of 1924, O’Hegarty was channelling the soft-authoritarianism and hostility to feminism that were already coming to characterise the Free State. But his arguments also drew on a well-established strand of Irish nationalist thought (and of nationalism more generally around the world): the notion that the national project was a masculine project, that the nation was defined by its fraternal unity, and that the nation-state would and should be led by men. Such predilections not only denied women’s right to an equal role in nationalist politics, but also meant that male political opponents were accused of being the ‘wrong’ kind of men; this was certainly the case in the political debates surrounding the Treaty and the outset of the civil war.

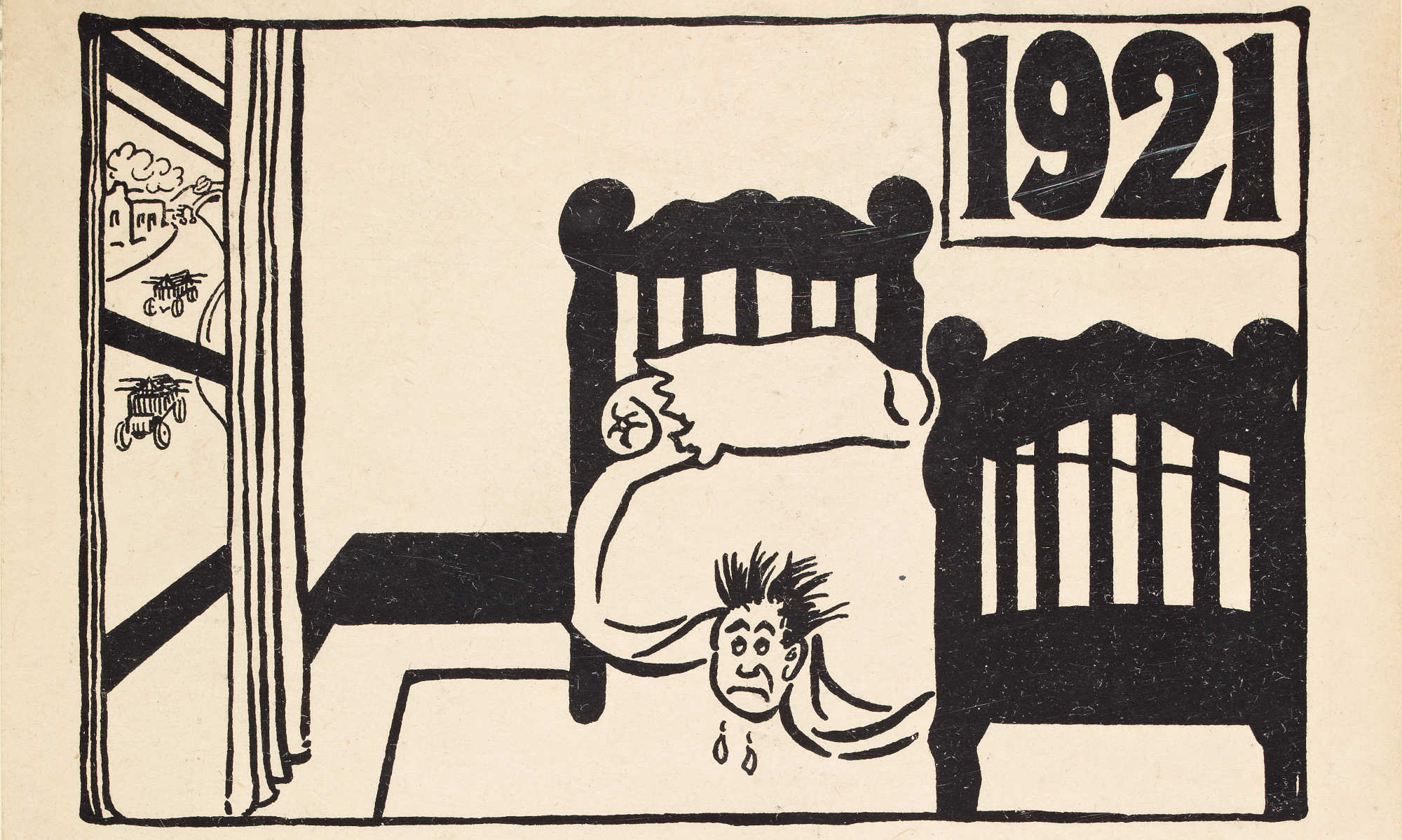

VIEW: Full version of the pro-Treaty handbill above

Constance Markievicz was one of the paradigmatic of these civil war-era ‘furies’. In furious style, she produced an evocative series of hand-drawn posters, now preserved at the National Library of Ireland, which caricatured the treatyites as ‘Free State Freaks’. She portrayed the newly elected president of the Executive Council, W.T. Cosgrave, as a Union-Jack-waving ‘Jester in Chief to the Freak State’. The minister for defence, Richard Mulcahy, was a gruesome Macbeth-like character, haunted by the dreams of the Irish men he had executed. The minister for posts and telegraphs, J.J. Walsh, was a dissolute figure, whilst Minister for External Affairs Desmond FitzGerald was presented as a preening liar of seemingly indeterminate gender, a servile functionary of the ‘slave state’. Anti-treatyite propaganda from 1922 also described Free State supporters as ‘Seoinins’, ‘Spineless worms’, ‘Slave Staters’, ‘recreant Irishmen’, and ‘Unnatural enemies’. In general, the Irish Free State was depicted as a ‘craven state’ and the embodiment of ‘Rotten Means and Men’. A contemporary open letter to members of the Free State army raised some pointed questions about where the pro-Treaty side fitted into the schema of nationalist time:

Have you ever read Irish History? If you have. Pause! Think! Let your conscience answer. Why are you fighting for England? Who are your Historical Comrades in the centuries old persecution of Ireland? The Priest-Hunters of the penal days. The Yeoman Pitch-Cap Brigade of ’98. The Proselytisers and Soup Providers of the Famine Days. The Police and Militia of ’67. The R.I.C. and the Black and Tans of 1916–’21. England equipped and armed these degraded allies in all her needs, and sent them to do her dirty work. To torture, maim and murder the true men whom Ireland honours…Do not carry on a war for England that will make your kinsmen in the present and your posterity in the future generations hang their heads with shame. Come over while ye may to the side of Ireland—your motherland. Let England find others degraded enough to do the devilish work. Line up with Tone, Emmet, Mitchell, Pearse, Connolly, MacSwiney, and Brugha.³

Anti-treatyite propaganda set up a claim that ‘the true men’ of Ireland were on their side and that ‘true men’ from the nation’s past, if they were alive, would never support the Treaty.

Such gendered rhetoric was certainly not the sole preserve of the anti-treatyites. Free Staters regularly portrayed their republican opponents as men unable to take control of the freedom now presenting itself, unable to take responsibility for their actions. Anti-treatyites were often dismissed as ‘trucileers’, dastardly men too cowardly to fight the English in the War of Independence, but who now attacked their fellow Irishmen and adhered to an irrational (that is, hysterical and feminised) republicanism. Batt O’Connor, soon to be a member of Cumann na nGaedheal, remarked at the outset of the civil war:

the strangest thing of all is the number of weaklings who now are talking big, but who were very mute and done [sic] damn little when the reign of terror was sweeping over the land…I know men who resigned even from our local Sinn Féin club through sheer cowardice of the Black and Tans and now they say they stand for a Republic and ‘will not let down de Valera’[.] These same fellows did not visit my house for 9 months when I could not sleep at home fearing they would be marked men if they were seen friendly with O’Connor or visiting his house.⁴

Kevin O’Higgins, rapidly emerging as a dominant treatyite figure, was aghast at the changes he saw in de Valera, accusing him in March 1922 of becoming a deeply irrational ‘fury-ridden partisan of the wild words and bitter taunts, the leader of men whose methods are rapidly degenerating into emulation of the “Black-and-Tans”’. O’Higgins would later claim that centuries of English rule had left Irish men without ‘political faculties’ and with little in the way of ‘civic sense’. Thus, anti-treatyite republicans were ignorant that ‘man is a social being and not a wild animal’.⁵

Many nationalist movements around the world have followed this pattern, with male interests generally being to the fore and political divisions understood via masculine lenses, with women’s concerns relegated to a secondary status if not ignored completely.⁶ P.S. O’Hegarty’s accusations were representative of a broad swathe of treatyite and anti-treatyite politics and pointed to a bigger debate in Irish nationalism about women’s equality and the role women should play in a future Irish state. Ultimately, this was to be a debate that feminists lost. W.T. Cosgrave, newly installed as president of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, pined for a gendered public–private split. He felt that rather than being involved in anti-Treaty politics, women ‘should have rosaries in their hands or be at home with knitting needles’.⁷ Éamon de Valera, who a decade later would take power, backed away from fully supporting the radical anti-treatyites: ‘I must be the heir to generations of conservatism’, he informed Mary MacSwiney in a letter in September 1922. ‘Every instinct of mine would indicate that I was meant to be a dyed-in-the-wool Tory or even a Bishop, rather than the leader of a Revolution’.⁸ Whether or not 1922 marked the final year of a political revolution, it was not the final year of a sexual revolution!

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.