12 September 1922: The Dáil Debates Unemployment

A Gaelic Economy? Financing The Irish State

by Jason Knirck

At a sitting of the third Dáil on 12 September 1922, as the government’s handling of the civil war came under attack, long-time Sinn Féiner Darrell Figgis criticised President W.T. Cosgrave’s refusal to provide an economic plan upon his election as president of the Executive Council and demanded he set an early date to discuss taxation policy. As the deputies continued to debate the economic direction of the new state, Minister for Agriculture Patrick Hogan, not particularly known as a Gaelic enthusiast or Sinn Féiner, said, ‘I hope we are not going to slavishly copy England. I hope we have some Gaelic social and economic ideals’.¹ Hogan was echoing earlier musings of Michael Collins, who wrote, ‘We want a modern edition of our old Gaelic Social polity—a thing that…grows naturally out of our own Irish character and requirements’.² When the government produced its first official budget in 1923, George Gavan Duffy told the Dáil, ‘let it not be forgotten that we are laying the foundations of a new Irish fiscal system’.³

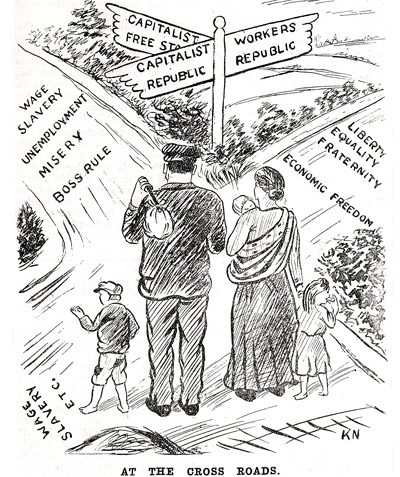

The belief that the Irish Free State would create a fiscal system that would be both post-colonial and Irish was widely held. These anticipated economic changes were part of what revolutionaries called the ‘Gaelic state’. Although efforts to revive the Irish language and Irish literature received the most pre-revolutionary attention, the Gaelic state was also assumed to encompass an Irish fiscal system and an Irish political system. This Irish fiscal system was usually left undefined, but revolutionaries assumed that such a system would express an Irish way of doing things and right the perceived wrongs of the colonial era.

Taxation, colonialism and identity have always been intertwined in Ireland, and Sinn Féin certainly emphasised these connections in its revolutionary propaganda.⁴ The party argued that Irish economic development had been deliberately sabotaged by the metropole through over-taxation, expensive Dublin Castle government, and dumping of British-manufactured goods.⁵ Its supporters promised to reverse this underdevelopment by means of tariffs. Sinn Féiners were also eager to demonstrate that a post-colonial Irish state would be sufficiently successful to reverse perceptions of the Catholic Irish as incapable of self-government. While generally most Irish politicians of the era agreed that Ireland was over-taxed and underdeveloped, there was no consensus on the necessary remedies.

Once the Treaty was ratified, politicians began articulating the shape of their desired fiscal system. These views were built on different interpretations of what constituted Irishness and what colonial remnants needed most to be dismantled in order to promote an ‘Irish’ system. The resulting debates were therefore tied to larger questions of the nature and identity of the new state and its inhabitants. Cumann na nGaedheal, the governing party, saw Ireland as a small European nation like Denmark or Belgium:an agricultural exporter seeking wider markets. The government was also obsessed with attracting investment and balancing the budget, believing such fiscal prudence would refute colonial stereotypes of the Irish as irresponsible and ungovernable.⁶ Introducing the Irish Free State’s first annual budget, Cosgrave said:

I think it is a matter of some satisfaction that we have passed through the troubled year just ended without serious embarrassment. The anticipated deficit for the coming year is, no doubt, serious, but it is not such as to cause any misgiving as to the financial future of the Free State and the credit of the country.⁷

He proudly boasted during a 1927 election speech that the Free State had a better credit rating than Belgium, indicating that his government had reversed the Irish reputation for unruliness and joined the ranks of fiscally responsible small European nations.⁸

Opposition parties, unsurprisingly, held completely different views. The Labour party believed that an ‘Irish’ fiscal system would develop Irish industries and ease the plight of labourers while moving toward a workers’ republic. To this end, Labour advocated policies that rewarded investment in Irish industries and purchases of Irish goods. Their proposals included tax penalties on investments outside of Ireland and stipulations that those receiving government salaries must purchase Irish-made goods. Labour leaders also recognised that the colonial period had restricted the Irish economy and prioritised the financial markets of the metropole, but wanted to use tax law and fiscal penalties, rather than patriotic volunteerism, to remedy this. Labour also wanted to reduce taxes on staples and everyday consumables, the remnants of a tax system that they felt disproportionately affected the working classes.

The Farmers’ party took very different lessons away from the colonial period. The Farmers saw Ireland as an agrarian country whose gains through land purchase were threatened by high taxes, especially local rates, and uncompetitive labour costs. They wanted a post-colonial Ireland with low taxes and rates, a minimal central state and spending priorities that reflected Ireland’s fundamentally agrarian nature, such as agricultural education and marketing. Their vision of an ‘Irish’ fiscal system was one of reversing the British legacies of over-taxation and centralised government.

Anti-Treaty Sinn Féin also articulated a different fiscal vision, although it took socialist-leaning politicians such as Seán Lemass and Constance Markievicz some time to convince republicans to focus on issues other than the Free State’s imperial ties.⁹ Anti-treatyites embraced Arthur Griffith’s notion of developing Irish industry behind tariff walls. Like the Farmers, republicans envisioned a state substantially less centralised and less dependent on career officials. The anti-treatyites’ interpretation of an ‘Irish’ tax code emphasised breaking remaining economic ties with Britain through tariffs and the withholding of land annuities. They also wanted to reward investment in, and purchases from, Irish industries. In fact, what became the Fianna Fáil vision for an Irish fiscal system was a combination of the Farmers’ attack on expensive career officials, Labour’s promotion of Irish industry and Griffith’s arguments for tariffs.

These broad disagreements were revealed through specific clashes on issues that transcended mere budgetary questions. Sinn Féin dissenters like Figgis and Gavan Duffy attacked the government for its wholesale adoption of the British taxation and tariff system that protected industries not extant in Ireland. Instead, they promoted an ‘Irish’ taxation system that fostered particular Irish industries. The taxation of Irish citizens who had invested in London markets also stirred debate. The government proposed relief from double taxation on such investments, while Labour bitterly opposed what it considered unpatriotic and unproductive capital flight. Labour instead argued that wealth that was not used to promote Irish economic development should be taxed heavily, thus reversing what they saw as colonial dependence on metropolitan financial markets. Cumann na nGaedheal and the Farmers both sought a system that remedied over-taxation, but the Farmers saw local agrarian ratepayers as the hardest hit by the phenomenon, while Cumann na nGaedheal often designed its tax cuts to attract British wealth and investment. As Ernest Blythe said, ‘if we could only induce one millionaire to come here to die, the [fiscal] advantages would be very great’.¹⁰

By the later 1920s the performance of the post-independence economy was at least as important as constitutional issues in electoral campaigns. The need to focus on economic matters was recognised as early as 1922, even given the initial attention directed toward dealing with various remnants of the imperial system. Each party drew fiscal lessons from aspects of revolutionary ideology and the perceived legacies of the colonial period. While the economic shortcomings of Cumann na nGaedheal are well-known, the initial debates over taxation demonstrate a shared desire to make the new state’s fiscal system Irish, and an inability to agree on a definition of such a system.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.