1 May 1922: Dublin Corporation Calls for the Censorship of Films

Keeping Hollywood’s ‘Monkey House’ Morality Out Of Ireland

by Kevin Rockett

On 1 May 1922 the motion that ‘Dáil Éireann be asked to appoint a Board of Censors for all Ireland’ was passed unanimously by Dublin Corporation.¹ This request came twenty months after Dáil Éireann had considered the introduction of national film censorship,² while a conference of anti-cinema activists held in Dublin in December 1921 had demanded that an independent Irish government introduce such a film censorship regime.³ These events were the culmination of campaigns by cultural, political and religious activists that had their roots in the late nineteenth-century agitation against what was perceived as immoral and anglicising imported popular culture and media. These campaigns acquired a new frisson with the increasing popularity of American cinema by the early 1910s.

For the decade prior to 1922, two competing worldviews—one embodied in Irish-Irelander nationalist, Gaelic culture, the other originating in Hollywood’s ‘dream factories’—had been accelerating towards collision. Notwithstanding the former’s longstanding anxiety regarding ‘the anglicisation of Ireland’, it was American cinema in the 1910s, with its increasingly transgressive elements (such as references to extra-marital affairs and divorce), that proved central in unifying Irish opinion—across religious and political divides, from cultural and political nationalists to unionists—to seek tighter controls over cinema.

The first legal mechanism through which censorship came to be imposed was the Cinematograph Act (1909), even though it had been designed as a public safety measure only. The courts began interpreting the 1909 act as allowing local authorities to regulate film content, such that in September 1916 a film censorship panel was set up by Dublin Corporation following pressure from the Catholic activist body the Irish Vigilance Association. In addition to the elected members of the corporation, this panel included appointees of both the Catholic and Protestant archbishops of Dublin.⁴ Given that the panel only viewed films after their release, considerably reducing its effectiveness, and that relatively few films were banned—76 films in the period 1917–21—calls for a more rigorous national approach followed. This led to Dublin Corporation’s motion on 1 May 1922.

The corporation’s motion had been proposed by alderman Joseph MacDonagh, TD, brother not only to 1916 leader Thomas, but also to John, whose feature-film adaptation of William Carleton’s anti-sectarian novel Willy Reilly and his Colleen Bawn, a key Irish film text, had been released on the Rising’s fourth anniversary.⁵ The motion was seconded by the longtime social and political activist, Jennie Wyse Power, chair of the Public Health Committee, which regulated cinemas.

Exactly a year later, in May 1923, the Censorship of Films Act was passed by the Dáil. Minister for Home Affairs Kevin O’Higgins introduced the bill following a meeting with an inter-denominational delegation of anti-cinema activists. The consensus against cinema also found expression in the Oireachtas. While reservations were voiced by the Labour party leader Thomas Johnson, TD, concerned that some provisions might restrict certain political views, and poet and senator W.B. Yeats, who argued for personal choice rather than state censorship, the repressive impulses of the new state were expressed most forcibly by William Magennis, TD, Professor of Metaphysics at University College Dublin, who suggested that people repeatedly found in breach of the act ought to have their citizenship revoked!

The Censorship of Films Act (1923) states that a film cannot be shown in public unless the film censor is satisfied it does not contain elements deemed indecent, obscene or blasphemous, or if it is determined that its public screening would ‘inculcate principles contrary to public morality or would be otherwise subversive of public morality’; the latter an all-embracing subjective provision that came to be widely used by censors.⁶ These criteria remain the reference points for present-day censors, as the act, albeit with amendments, remains on the statute book. The 1923 act also lays down the provision that an Official Film Censor be appointed, and that the censor’s decision can be appealed to the Censorship of Films Appeal Board, a voluntary nine-person committee, which can confirm, alter or amend the censor’s decisions.

While the first Official Film Censor James Montgomery (1923–40) boasted he knew nothing of film, but took the Ten Commandments as his guide, the members of the appeal board, who included Yeats, who resigned after ten months, and Wyse Power, who remained for over a decade (1924–38), tended in the main to reflect conservative Catholic and anti-modern views. From the outset, appointments, made by the Department of Justice, which still administers the office, included a representative from each of the two archbishops of Dublin, and excluded film distributors and exhibitors, and culturally liberal or internationalist voices.

Informed by the thesis that the family was the primary social unit of the state, and his belief that the laws of the land were sacrosanct, Montgomery set about his task with gusto: banning 100 films in his first year, the average for each of the seventeen years of his tenure. (The appeal board only occasionally reversed or modified his decisions.) With no differentiation made between representation and reality, all representations that contravened Irish law or were deemed deviant (including images of, or references to, marital infidelity, divorce, homosexuality, abortion and sexual assault), or that were contrary to Victorian morality (such as Jazz Age depictions of women in revealing clothes, in night-club chorus lines, smoking or drinking alcohol), were cause for a film to be banned or the objectionable scenes removed.

In February 1924 distributors, shaken by the severity of the new regime, withdrew their films from the Irish market. In a riposte, the censors declared they would rather have no films than the ones being submitted. Supported by the government, the censors resisted the distributors’ pressure and within four months the boycott was lifted.⁷ Thereafter, the censors had a free run, such that from the 1920s to the 1980s about 2,500 films were banned and another 10,000 to 12,000 cut. There was little or no public debate regarding the censorship process, as all censor files were hidden from public scrutiny until 1998, when they were deposited in the National Archives of Ireland.

A number of 1922 films came before the censor in 1923 and 1924. Among those banned were ‘the very ugly picture’ The woman who walked alone, which had ‘most objectionable’ scenes featuring a farmer’s wife infatuated with another man; The ordeal, similarly described as ‘an ugly story’; A woman’s woman, ‘a sordid story of conjugal infidelity, suggested seduction, attempted suicide, murder [and] divorce’; the ‘morbid and unhealthy’ Queen of the Moulin Rouge, featuring a dancer at the Parisian nightclub; and the Jazz Age Nice people dismissed as the ‘usual picture of this type—wade through nastiness to a “moral end”’.⁸

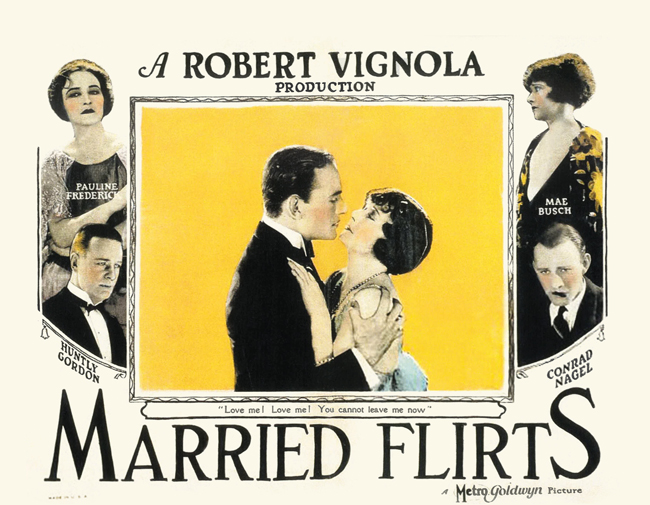

Montgomery’s motivation is most clear in his report on the 1924 film My husband’s wives which he also banned: ‘the remarriage of divorced people is illegal in Saorstát Éireann [and] I consider it “subversive of public morality” to allow exhibition of it’, because ‘the monkey house morality begotten of such a social condition is apparent’.⁹ As for the same year’s Married flirts, in which ‘the “morality” of the cave and the monkey-house is the ruling code’, it contained ‘all the unhealthy materials which made censorship necessary’,¹⁰ a comment validating the need for Dublin Corporation’s motion of 1 May 1922.

Notwithstanding the censors’ culling, what is perhaps surprising is that cinema-going in Ireland remained central to people’s lives throughout this period; a cause of concern for those same censors, some of whom would have preferred its total prohibition. Though Ireland’s cinema screens may have been sanitised, it seems the private fantasy lives of the people excited by film, and indeed by the cinema space, could not be fully suppressed.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.