1 February 1922: Frank Walsh’s American Imperialism

Irish Revolution and American Empire

By David Brundage

On 1 February 1922 the Irish American political reformer Frank P. Walsh published an article in the liberal US weekly, The Nation. Unlike many of his other publications over the previous few years, this short opinion piece did not concern Ireland. Walsh focused instead on the US military occupation of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and the thrust of his analysis was summed up in the article’s two-word title: ‘American imperialism’.¹ Nonetheless, Ireland’s recent history was not far from his mind. As he argued forcefully in his article, British policy in Ireland provided a near-perfect prism for understanding what was currently transpiring in the Caribbean.

Difficult as 1922 was for Ireland, it was also a challenge for American liberals like Walsh. By the end of 1921 political conservatism was ascendant. Both Democratic and Republican party leaders had abandoned the progressivism that had shaped much of the US political landscape for the previous two decades. Big business was dominant in Washington, D.C. and efforts to regulate the market on behalf of workers and consumers had been effectively blocked. Black Americans and immigrants from Asia and eastern and southern Europe faced a rising tide of racism, while trade unions had suffered defeats in a number of dramatic post-war strikes.

Over the course of 1922, however, a new kind of progressive coalition began to take shape, one that placed what the social reformer Jane Addams called ‘a nascent world consciousness’ at the centre of its political vision.² Integral to this perspective was a bracing critique of US imperialism. There were many factors shaping this critique, which would culminate in Robert La Follette’s Progressive party presidential bid in 1924. The Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, which Addams had helped found five years earlier, embraced a new moral realism that subjected US foreign policy to the same scrutiny as that of other great powers. Black leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois grew increasingly critical of both American and European colonialism, and labour radicals began to explore new forms of international working-class solidarity. But equally important was a small group of liberal and left-wing Irish Americans who had worked assiduously to build US support for the Irish revolution. Frank Walsh was one of these.

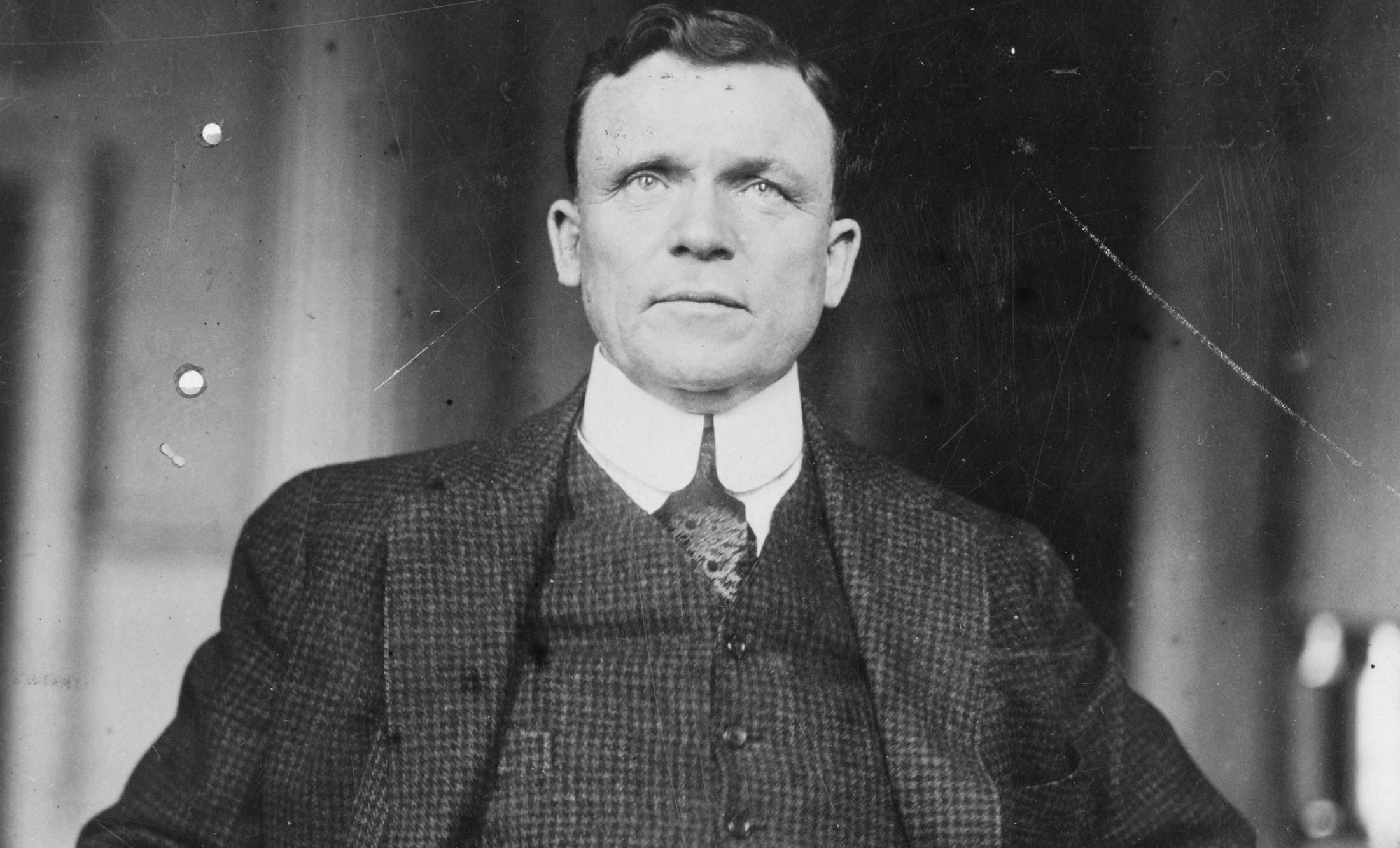

Born to a working-class family in St Louis’s immigrant ‘Kerry Patch’ in 1864, Walsh had come of age politically as a labour lawyer and reform Democrat in turn-of-the-century Kansas City. He went on to serve prominently in both of Woodrow Wilson’s administrations, first as chair of the US Commission on Industrial Relations (1913–16), which drew public attention to the abusive power exercised by the nation’s largest corporations, and later as co-chair of the National War Labor Board (1918), which consistently ruled in favour of workers and helped prepare the ground for the pro-labour policies of the later New Deal era. An exponent of a Catholic-based vision of social justice, Walsh remained a passionate advocate for working people, arguing in April 1922 that the case for a ‘living wage’ was ‘one far above the law and went down into the deepest moral questions, the structure of society, and even into fundamental religion’.³

Walsh was also a major figure in transatlantic Irish republicanism. At the February 1919 Irish Race Convention, he was picked to chair the American Commission on Irish Independence, a group of three prominent US citizens who travelled to the Paris Peace Conference with the goal of winning an international commitment to Ireland’s independence. Their mission failed, but Walsh subsequently advised Éamon de Valera during his American tour of 1919–20 and took the lead in organising the US sale of Irish bond-certificates, which raised over $5 million for Ireland’s revolutionary government. In 1922 he cast his lot with anti-Treaty forces and played a critical role in the New York legal battles to keep those funds out of the hands of the Irish Free State government. When Walsh died in 1939 de Valera hailed him as ‘one of Ireland’s truest friends’ and dispatched Robert Brennan, Ireland’s minister in Washington, to attend his Kansas City funeral.⁴

Walsh was no narrow Irish nationalist, however, but rather a committed opponent of imperialism in general. In a December 1918 speech in New York, he lashed out at the British empire, emphasising not Ireland, but Egypt, where ‘for 50 years England has continued its grievous assaults’.⁵ While in Paris the following spring, he reached out to Sa’d Zaghlul, who was working to put the Egyptian independence case before the Peace Conference and who asked Walsh to serve as ‘Egyptian Counsel’ in the United States. An arrangement worked out by Seán T. Ó Ceallaigh (who was also in Paris, representing the Irish Republic) provided Walsh with $90,000 in expenses and fees. Once back in New York, he used some of this money to found an organisation called the League of Oppressed Peoples, whose ambitious goals were ‘to defeat militaristic aggression and to secure self-determination for all peoples’. With representatives from Ireland, India, Korea, and sub-Saharan Africa, the league presented the Irish cause as an integral part of a movement of all those oppressed by imperialism.⁶

In 1922 Walsh extended his critique to include American conduct in the Caribbean. Though justified by a rhetoric of ‘benevolence’ that administrators of the British empire would have understood, the US military occupation of Haiti (1915–34) and the Dominican Republic (1916–24) was motivated mainly by a desire to cement American control of those two neighbours’ economies and to protect the new and strategically important Panama Canal. US marines soon found themselves fighting local rebels (known in Haiti as Cacos) and, in response, burned entire villages and brutally executed those they believed to be rebels. These were the events that prompted Walsh’s angry Nation article.

‘The American Foreign Office is in Wall Street. Its agents are the Imperial General Staff in Washington’, he began, observing sadly that ‘the imperialism which our ancestors resisted our present rulers have condoned and practiced to our national disgrace’. Especially troubling to Walsh were the parallels with British policy in Ireland:

In the story of these subjugated [Caribbean] republics American atrocities take the place of British atrocities. Padraic Pearse, Connolly, and Kevin Barry have French and Spanish names; and the ‘murder gang’ are called Cacos and bandits instead of Sinn Feiners; otherwise Haiti and Santo Domingo might be Ireland.

Walsh ended his piece with a call to action. Just as Irish men and women had struggled to force ‘British Imperial Forces’ from the soil of Ireland, so now ‘all true Americans and all true Irishmen’ should work to drive ‘the Imperial United States Forces from the republics of Haiti and Santo Domingo’. Over and over again through the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Irish nationalists had stressed the sharp distinction between ‘republican’ America and ‘imperial’ Britain. Walsh emphasised the similarities.

Walsh’s views were not widely held among Irish Americans. But they were not totally out of the mainstream. Many Irish nationalists had opposed the US acquisition of Puerto Rico and the Philippines as colonies after the Spanish–American War (1898), and even the moderate Friends of Irish Freedom provided financial support for the League of Oppressed Peoples. ‘When one understood British imperialism, it was an open window to all imperialism’, the famous Irish American radical, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, once observed.⁷ Frank Walsh would have agreed.

Extracted from Ireland 1922 edited by Darragh Gannon and Fearghal McGarry and published by the Royal Irish Academy with support from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media under the Decade of Centenaries 2012-2023 programme. Click here to view more articles in this series, or click the image below to visit the RIA website for more information.