Trinity College Dublin and Gallipoli

by Dr Tomás Irish

Following Trinity College Dublin’s recent unveiling of a specially commissioned memorial stone honouring staff, students and alumni who died in the First World War, Century Ireland reproduces a paper on Trinity College and the Gallipoli campaign, written by Dr. Tomás Irish. A Lecturer in Modern History at Swansea University, Dr. Irish is the author of Trinity in War and Revolution 1912-23 (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy Press, 2015).

***

Trinity College Dublin has a deep connection to both the First

World War, and, in particular, the Gallipoli campaigns. Over the

course of the war, just over three thousand undergraduates,

graduates, and staff members performed some sort of military

service, with the vast majority doing so as volunteers. By the end

of the conflict, 471 of these men (and one woman) had died, in

arenas as disparate as France, Belgium, Mesopotamia, German East

Africa, West Africa, Egypt, Germany, and Italy. However, the

Dardanelles campaigns hold a special place in the story of

Trinity’s involvement in the war. Fifty-four Trinity

students, staff, and alumni died in the Dardanelles campaign, and

losses were particularly severe in the fighting at Suvla Bay in

August 1915, where the 10th (Irish) Division suffered terrible

casualties.

RTÉ News reports on the unveiling of a memorial stone at the Hall of Honour, in TCD’s Front Square on Saturday 26 September 2015.

The fighting at the Dardanelles stands out in the history of Trinity in this period because of the intensity and frequency of death which occurred there: in August 1915, 41 Trinity men, or almost ten percent of the total to die in the war altogether, died in the course of fighting at the Dardanelles. On two days, the 15 and 16 of August 1915, twenty men were killed at Suvla Bay. Trinity College Dublin, then, has its own specific and traumatic relationship with the Dardanelles campaign, which both mirrors the wider Irish experience of that campaign, but which also retains much which is specific to the institution. This piece will discuss some elements of the Trinity experience of Gallipoli, putting Suvla Bay in a wider context of Trinity involvement in the war, from enlistment, to experience of fighting, and memory. The final point is important: the dates 15-16 August are perhaps the most traumatic in the entire history of an institution which is over 420 years old, yet there is little institutional or popular memory of this.

Background

In 1914, Trinity College Dublin was a middle class, mostly

Protestant, and politically influential institution. Located at

the heart of Dublin and with a population numbering around 1,200

students and staff, it trained men – and it was mostly men

– for careers in professions such as Law, Medicine,

Engineering, or the Church of Ireland, and many others beside. A

Trinity degree opened up possibilities in the professional worlds

which took the holder far from Ireland, and many graduates made

their lives in far flung parts of the British Empire, such as

Canada, India, and Australia. As such, the university had a strong

connection to the Empire based on professional ties, but it also

had strong ties to the Empire through its political connections.

The university was traditionally a unionist institution whose

graduates elected two Members of Parliament to Westminster. These

men were themselves influential and visible unionists: Sir Edward

Carson and James Campbell. The university was not, however,

uniformly unionist: by the outbreak of war in 1914, there was a

growing number of Home Rulers amongst the student body, but there

was little in the way of political radicalism or revolutionary

nationalism amongst students. As such, the institution

enthusiastically pledged itself to support the war from its

outbreak in August 1914.

Students or alumni were enthusiastic in joining the colours in these early months of the war and the majority of Trinity enlistment took place in this period. 224 men, or seven per cent of the overall total, volunteered for service in August 1914. By the end of 1914, this figure was 725 (twenty four per cent of the total). A further 785 men enlisted in 1915 (twenty five per-cent of the total). Numbers dropped off markedly from 1916, with 284 men volunteering that year (nine per cent of the total), 193 volunteering in 1917 (six per cent), and 134 in 1918 (four per cent). Broadly speaking, Trinity recruitment trends overlap with enlistment patterns in Ireland, and were testament to the enthusiasm for war in its early months.

Why did students and alumni enlist in such volume? Some reasons were no different than those cited by men in towns and cities across Ireland, Britain, and the wider world. Conscription was never enforced in Ireland and all men who enlisted in the armed forces did so voluntarily. A Catholic undergraduate, Walter Starkie, recalled that men enlisted in the armed forces in great numbers as early as 4 August, the day that war broke out in Europe. While there were often factors specific to Trinity which motivated men to enlist, often the reasons were no different to those of other Irishmen, irrespective of class, creed, or political views, or of young men across Europe.

The mechanism through which students could gain commissions in the

army was the Officers Training Corps. OTCs were set up at

schools and universities across Britain from 1907, as part of a

programme of army reforms. They gave students specialised

military training, allowing them to quickly gain commissions in

the army as junior officers in wartime. The OTCs quickly became

popular for their own sakes; they were sociable and provided

students with a distraction from purely academic matters.

Trinity College’s OTC was set up in 1910. The OTC

established a parade ground on the east end of the College Park

and drilled there daily. The OTC had around 400 members, or one

third of the overall student population in the years before the

war. Consequently, student life was significantly militarised

before war broke out. When the conflict erupted, men flocked to

the OTC, both from inside and outside of Trinity, recognising that

it would provide them with a quick means of gaining a commission

for the army.

Trinity had a long connection to the British Empire, through the

Indian Civil Service, the Engineering School, and the Medical

School, and the Church of Ireland, and many in the university saw

support for the war as a continuation of this strong imperial

association. Imperial affinity linked political ideologies,

professional aspirations, and the social identity of students, and

this was a common theme in universities within the British

Empire.

Many Irishmen enlisted due to the political ideas of the war.

Superficially conflicting political aspirations – such as

unionism (both Ulster and Southern) and Redmondite nationalism

– found common cause in support for the conflict; in each

instance, it was an opportunity to prove loyalty of the respective

cause to Westminster in the hope of gaining favour in return.

Trinity was traditionally a strongly unionist institution and many

felt that support for the war effort was in the best interests of

maintaining the union between Ireland and Britain. Similarly, the

growing number of Home Rulers among the student body felt that

support for the war would be a show of goodwill towards the

British government. Home Rule was placed on the statute books in

September 1914, to become law once the war ended. The events of

1914 presented a watershed moment where cooperation replaced

antagonism and previously suspicious factions were united in the

common cause of the war, and this blurring of the lines between

nationalist and unionist was certainly experienced at Trinity.

P.L. Dickinson enlisted with a number of Trinity men, including the Reid professor of Law, Ernest Julian, who joined the 7th RDF, in September 1914, following John Redmond’s famous speech at Woodenbridge in Co. Wicklow. Dickinson wrote that:

Numbers of Dublin men, like myself, thought 'Well, I don’t belong to his party, but he has done the big thing. Let us shake hands, and we will join up in the Irish volunteers, pledged by John Redmond to the cause of the Allies.'

Noel Drury, who enlisted through the College’s OTC and ended up serving at Suvla Bay with the 6th RDF, noted the unusual change which came about through this sense of shared purpose amongst Home Rulers and Unionists in the Spring of 1915:

Good Presbyterians like myself paraded and marched off to the tunes of the “Boys of Wexford” and “A Nation Once Again” and went to chapel for the first and, probably, the only time in our lives. What a change the war has brought over things to be sure. If anyone had told me a year ago that I would have marched to a R.C. chapel to a rebel tune, I would have said they were potty to say the least of it.

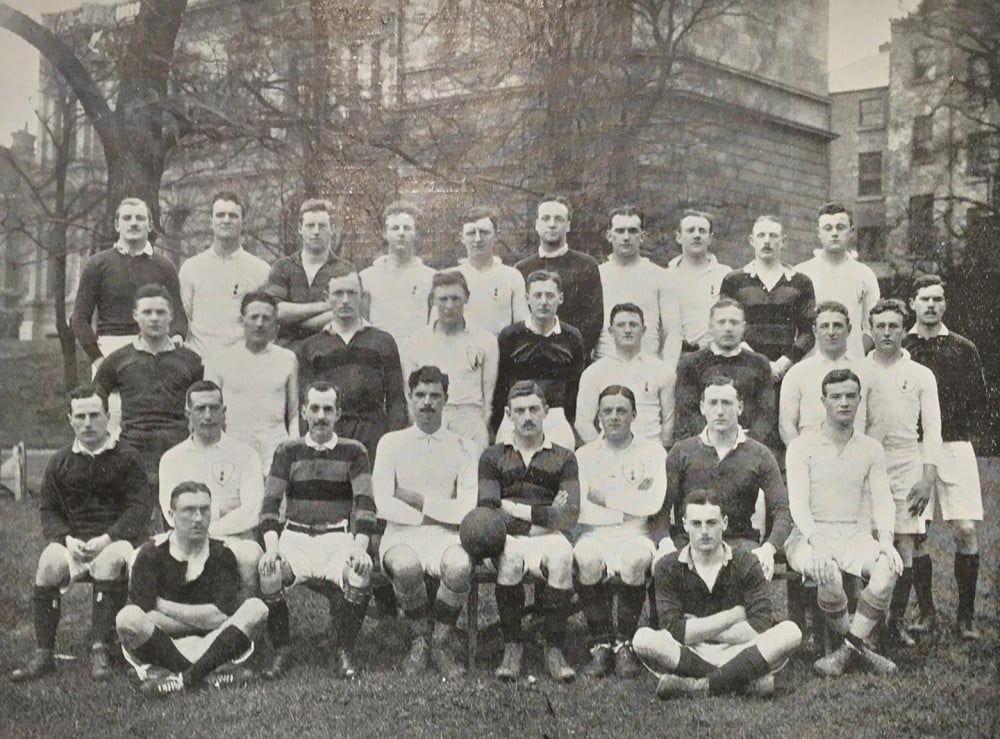

The rugby teams of the D Company RDF and the 3rd Infantry Brigade. Some members of the D Company would have enlisted and served together in a Pals battalion. (Image: (Irish Life, Vol 12, March 5th 1915)

More striking than this was the group dynamic, a phenomenon which can be seen in schools, universities, clubs, and workplaces in all societies where conscription was not enforced. It spoke to the intimate bonds of loyalty which formed in the course of a university education where adolescents became men, spent long hours living, studying, playing sport, and socialising together.

This group dynamic – the phenomenon which saw men seek to enlist and serve together – saw its best manifestation in the case of the Dublin Pals, D Company of the 7th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, men who chose not to seek a commission as an officer but to fight alongside their friends. There were 42 TCD pals in total (24 undergraduates and 18 graduates). The Pals were formed through the efforts of F.H. Browning, a recruitment activist, Trinity alumnus, and president of the Irish Rugby Football Union, who had recruited a 300 strong volunteer corps within weeks of the outbreak of war in 1914. These recruits became part of the new armies formed by Lord Kitchener in September 1914, and the majority of these men would end up seeing action as part of the 10th Irish Division when it landed at Suvla Bay on 6-7 August 1915.

Describing the motivations which impelled him to join the 7th RDF,

an undergraduate called Frank Laird described himself as a

‘man of peace’ but fretted over ‘the awkward

question of how my friends would regard me afterwards if they

found me still at home when the war was over.’

Meanwhile an article in T.C.D.: a College Miscellany – the

student newspaper - from November 1914 stated that ‘there

are still some Trinity men who have not come forward. This is no

time for moralising or for gloomy thoughts.’ It added that

those who had not yet come forward were ‘nothing short of

criminal.’ Starkie recalled that ‘I followed the

example of my college friends and went to a recruiting depot to

offer my services’, feeling a sense of ‘moral

obligation.’ Starkie was refused on medical grounds

but would later write that he personally lost eight close friends

at Suvla Bay.

During the war classes continued, although while there was a

desire for normality, this was impossible. In 1915 an editorial in

the student magazine stated that:

It would appear that the activities of us students cannot continue

unabated this session. The best men are away, and the hearts of

the rest of us cannot be wholly in our college life … the

bare fact is, that in so far as is possible, Trinity College has

laid aside the pen for the sword.

The war significantly reduced student numbers at Trinity but the campus was not empty. The number of undergraduates on the books fell from 1,285 in 1914 to 721 by 1918. In early 1915, T.B. Rudmose-Brown, Professor of French, reported that he had no students whatsoever for certain classes. Walter Alison Phillips, professor of history, noted in 1915 that his history classes were reduced to ‘four girls and a callow youth.’ As today, students were the lifeblood of the college and their absence underscored the abnormality of the situation. At the same time, the absence of men meant that women became much more visible in day-to-day life.

Gallipoli

The connection between Trinity College Dublin and the Gallipoli

campaign has generally been remembered in terms of the Pals

Battalion – the 7th RDF – and the terrible losses at

Suvla Bay. The Pals were composed of many middle class

professionals and sportsmen, who were typical of the TCD milieu.

However, Trinity’s engagement at Gallipoli was much wider

than this. Four alumni or students had been killed April and June

1915 at the Dardanelles, three of whom were professional soldiers

in regular regiments, while one was a student. Similarly, of those

who died at Suvla Bay in August, three were in Australian or New

Zealand regiments, while one was in an Indian regiment. The

experience of Gallipoli demonstrated the imperial trajectories

taken by Trinity alumni, such as Everard Digges la Touche, a

Church of Ireland clergyman who was well known in Dublin and who

emigrated to Australia in 1911 and enlisted in the Australian

forces at the outbreak of the war, killed on 7 August 1915

(memorialised at St. Patrick’s Cathedral).

Members of the Pals battalion in the Royal Barracks, Dublin before setting off for training in Basingstoke, ahead of the August landings at Gallipoli (Image: National Museum of Ireland)

However, I wish to focus on those Trinity men who were members of the 10th (Irish) Division, the men who volunteered at the outset, the majority of whom enlisted in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers (and also, in smaller numbers, in the Royal Munster Fusiliers). Having initially trained at the Curragh Camp, the 10th finally left Ireland at the end of April 1915 to undertake the final stage of their training in the south of England. As the Royal Dublin Fusiliers marched off, they were led by the pipers of the Trinity’s Officers Training Corps, further underscoring the link between the two. From there, they moved to a camp at Basingstoke, where they trained until the second week of July, 1915, before making their way to the Mediterranean, not yet knowing their ultimate destination. By the end of July, they had reached Alexandria, then the Greek islands of Lemnos and the city of Mitylene, in close proximity to the Gallipoli peninsula.

For many Trinity students and alumni, this journey was an evocative one. The majority of courses of study at the time required that students took a general course in the Arts, leading to a BA degree. The BA degree was heavily influenced by the study of the Classics and Ancient Greece, while many of the leading scholars at Trinity shared these interests. The legends of antiquity were well known to them, and their close proximity to Troy provided a parallel between their studies and their present situation. The unionist politician Bryan Cooper, who served at the Dardanelles and later wrote a book about his experiences, noted that ‘Many of D Company (" The Pals ") of the 7th Dublins were men who had taken degrees at Trinity or the National University, and they may well have recalled past studies and thrilled to remember that the word Samothrace [to the north] had always been associated with Victory.’ More practically, many tried to use their knowledge of Ancient Greek to buy luxury items from the locals, such as Noel Drury, of the 6th RDF. George Chester Duggan, a TCD graduate who, in 1921, wrote a long poem in memory of his two brothers who died at Suvla Bay, also drew on this classical allusion.

Argosies seeking out the golden fleece

Have sailed this way, and won a little lease

From Time’s great rent-roll in the script of Greece.

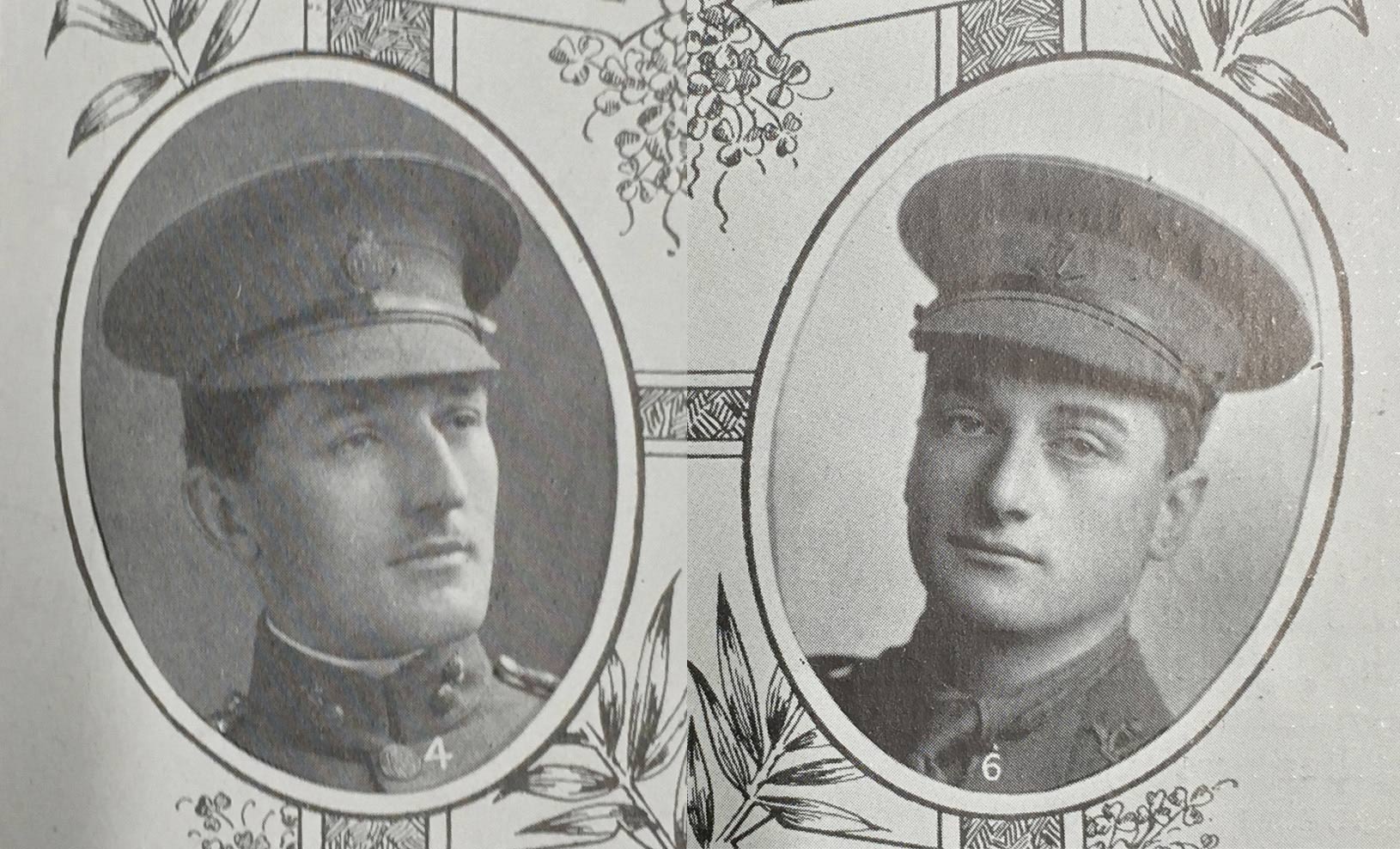

The landings at Suvla Bay took place from 6 August. Trinity men were soon being killed in their tens: three died on 7 August, three on 8 August, 4 on 9 August, four on 10 August, two on 12 August, 6 on 15 August and 14 on 16 August. There were notable casualties among them. Among those to die on 8 August was Ernest Julian, the Reid Professor of Law (a position later held by both Mary McAleese and Mary Robinson), whose final words as he lay wounded were ‘I am glad I have done my duty.’ The Duggan brothers, George Grant and Jack Roswell, both died on 16 August. George Grant Duggan had distinguished himself at TCD as an athlete and founder of Trinity Week. His brother was still a medical student at the time of his death. In a letter published in the Freeman’s Journal, the undergraduate Owen Gill , as signal officer in the Royal Engineers, recalled seeing lots of ‘Dublin University men, alive, and dead, and wounded: too numerous to mention here.’

George Grant Duggan (L) and his brother JR Duggan (R) were both killed at Gallipoli on August 16 1915. (Irish Life November 26 1915)

Many Trinity men wrote of their experiences in letters or extended accounts which were sent home for publication in newspapers. Poole Hickman was the commander of D Company. He was a barrister, former rugby player with Wanderers, and alumnus of Trinity. He wrote extensive accounts of his experiences which were published in instalments in the Irish Times. He left the reader under no illusions of the horrors of modern warfare conducted in the intense heat and difficult conditions of the Dardanelles. After a week Hickman wrote that: 'and all this time we have never even had our boots off, a shave, or a wash, as even the dirtiest water was greedily drunk on the hill, where the sun’s rays beat pitilessly down all day long, and where the rotting corpses of the Turks created a damnably offensive smell. That is one of the worst features here – unburied bodies and flies – but the details are more gruesome than my pen could depict.'

Hickman’s full account was published in the Irish Times on 4 September 1915, by which time he had been dead for two weeks, killed at midday on 15 August. Within minutes, the command structure of D company had disappeared, as Hickman’s replacements were swiftly killed in turn.

In a letter written to the student newspaper on 25 August 1915, Sergeant William Kee reported that he had been placed in temporary command of the Pals, ‘so that you may judge that we lost some’, before naming some of the Trinity dead. Kee did not seem disheartened by the destruction of his unit, while he acknowledged that ‘there will be great change in the personnel of the Company’, he claimed that ‘we are going on great out here.’ However, word of the particularly difficult conditions at the Dardanelles had got out. James Campbell, one of the university’s members of parliament, fretted over the safety of his son Philip who was serving at Suvla Bay and wrote to government minister Andrew Bonar Law to see if influence could be brought to have him taken out of the front line and given a safer job elsewhere. He was unsuccessful. The final Trinity man to die at Gallipoli was William John Law of the Lancashire Fusiliers, killed by a mine on 19 December 1915.

Memory

For such a traumatic event, hitherto there has been little

institutional memory of the depth of Trinity losses at Suvla Bay,

although some traces remain. There are two obvious reasons for

this lack of institutional memory. First, the fighting at Suvla

took place out of term time and as such it was not reported in the

student newspaper in real time. In fact, aside from the Kee letter

quoted earlier, references to the Gallipoli campaign are

relatively absent from the student newspaper. Perhaps it was

easier to say nothing than to deal with the enormity of the

institution’s losses. More obviously, following the Easter

Rising, the suppression of which Trinity played a conspicuous

role, the institution had to confront a serious challenge to the

values and political ideals which had sustained it for so long. In

this context, the memory of the war was not quite rendered taboo,

but would soon prove problematic.

In 1919 it was decided to build a memorial to those members of the TCD community who died during the war. War memorials of this nature catered to a human need to grieve in the aftermath of the collective suffering of the war and were erected in clubs, schools, universities, workplaces and towns across Europe. Shortly before his own death in May 1919, the Provost, John Pentland Mahaffy, proposed that the College war memorial should explicitly refer to the Dardanelles campaign. Playing on the classical analogies which underpinned a TCD education and informed how many soldiers understood their experience, he proposed that the memorial should take the form of the famous Nike of Samothrace sitting in the middle of Front Square, towering over all other buildings. This memorial would be a replica of the famous statue depicting the goddess of victory which dated to the 2nd century BC, was discovered in Samothrace in the 19th century, and housed in the Louvre in Paris. Following the Provost’s death, it was decided not to proceed with such a grand plan, and a more austere memorial was planned.

This updated project manifested itself in a Hall of Honour, built in conjunction with a new Reading Room for the library. The Provost who oversaw this was John Henry Bernard, a former Archbishop of Dublin who also lost a son at Gallipoli in May 1915. In 1928 the Hall of Honour, which cost just over £8,000 and was funded entirely by subscription, was formally opened by Provost E.J. Gwynn and Lord Glenavy, Vice-Chancellor of the University (formerly James Campbell). For the architect, Thomas Manly Deane, the commission was an especially important one: his son, Thomas Alexander Deane, had been killed at Gallipoli on 20 May 1915. Glenavy hoped that the Hall of Honour would provide solace to the families of the dead ‘by its perpetual testimony that when the call of duty came they neither faltered nor failed.’ At the inauguration ceremony in November 1928 he also referred to ‘a growing conspiracy of silence’ regarding the memory of the Great War in the Irish Free State. There were no representatives of the Irish Free State present at the 1928 ceremony.

The Hall of Honour took the form of a portico, with the names of the dead engraved on either side. On the outside of the building, facing out towards Front Square, is the simple inscription: NIKH, the one remnant of Mahaffy’s original plan which was retained and an oblique reference to the Dardanelles campaign, hidden in plain sight.

In 1928, Trinity College’s Vice-Chancellor Lord Glenavy in the presence of Provost E. J. Gwynn and invited guests officially opened The Hall of Honour in memory of those who died in the First World War. This is the British Pathé newsreel footage of the event.

Ex-unionist Trinity and the nationalist new state had a mutual suspicion of one another in the 1920s and 1930s, and thus it was deeply symbolic when Eamon de Valera, President of the Executive Council, was invited to inaugurate the new Reading Room – adjoining the Hall of Honour – in 1937. The event demonstrated that a rapprochement was taking place between university and state, but this came at a cost: none of the speeches referenced the Great War or Hall of Honour.

In the decades that followed, the Reading Room/Hall of Honour complex became known collectively as the ‘1937 Reading Room’, and the history of the building – and of Trinity’s experience of Gallipoli – was obscured for the generations of students and staff who followed. The unveiling of the World War One Memorial Stone, which occupies a hitherto empty plinth in front of the Hall of Honour, constitutes an act of reclamation of the memory of the First World War, and in particular the Gallipoli campaign, by the community of Trinity College Dublin.