The Vatican and the Irish revolution, 1914-1923

By Dr Jérôme aan de Wiel

Despite its transnationality, the Catholic Church was not a worldwide monolithic bloc and the Vatican would bitterly experience this during the First World War (1914-1918) and its aftermath. These events also formed backdrop to the Irish revolution (1912-1923), in which the papacy of Benedict XV would become seriously embroiled.

Relations between Catholic Ireland and the Vatican had not always been the best at the political level. In the 1880s, Pope Leo XIII had condemned the Plan of Campaign supported by Irish nationalists in return for British support against the Italian government’s plan to confiscate papal property. Moreover, it was his dream to reconvert Britain to Catholicism. There was no official British diplomatic representative to the Holy See but London relied on various individuals in Rome to advance its political goals, notably the appointment of Irish bishops.

Predictably, in future the Irish hierarchy would try to keep the Vatican out of Irish affairs as much as possible. Before the outbreak of the war, Pope Pius X had undertaken many reforms in the Church, but not so many in the field of international relations, although he had an interest in it. However, the Vatican’s informal relations with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland were improving. In 1910, the British removed the anti-Catholic clause from the coronation oath. The following year, a papal representative was present during the coronation of King George V and this paved the way for the eventual arrival of a formal British diplomatic mission to the Holy See in November 1914, although the war was undoubtedly a major factor in Herbert Asquith’s government decision for doing so as all the belligerents considered the Vatican a most important diplomatic listening post (the Vatican would officially become an independent state after the signing of the Lateran Treaty in 1929).

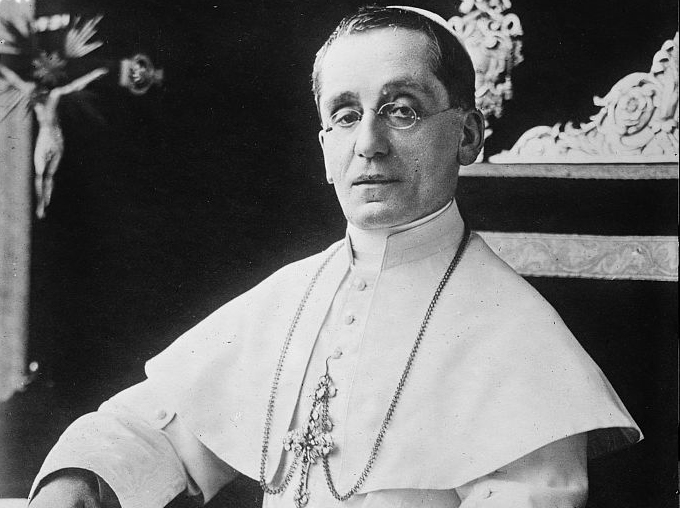

Pope Benedict XV in 1915 (Image: Library of Congress)

Just about a month into the war, Cardinal Giacomo Della Chiesa was elected Pope and took the name Benedict XV. He strongly believed in papal authority. Back in 1910, his Lenten Pastoral had been entitled ‘The Spirit of Obedience’. Yet, the war would show that his authority had limits as all national Catholic Churches in the belligerent countries believed that God was on their side. Initially, some among the belligerents had welcomed his election as he had been a diplomat and, importantly, had never been a nuncio in one of the belligerent countries. He therefore appeared to be neutral and was the right man to have been elected pope at this critical juncture.

To help him in his arduous task to bring about peace in the world, he was assisted by Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, an experienced diplomat who had served as apostolic delegate in different South American countries, and who became cardinal secretary of state, the equivalent of a foreign minister, in October 1914.

Bringing about peace in the world was going to be an unsurmountable task and that became clear from the very beginning. The Vatican adopted a policy of strict impartiality and essentially wanted to maintain the status quo between the great powers in Europe. Benedict XV made statements and took initiatives to mediate for peace. In his first encyclical, entitled Ad beatissimi, issued on 1 November 1914, he appealed to the belligerents to find a way other than war to solve their differences. In July 1915, he offered his mediation, and in August 1917 he issued a peace note. But all his efforts were rejected by the belligerent governments who sought to obtain moral condemnations of the enemy from him, something he would not do. J. Gregory, secretary to the British Mission at the Holy See, reported to London with a touch of frustration: ‘a spiritual authority can never be neutral’. French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau called him ‘le pape boche’ (the kraut pope), German General Erich Ludendorf named him ‘französischer Papst’ (French pope), and Italian anti-clericals nicknamed him ‘Maledetto XV’ (Cursed XV).

What they failed to understand was that the head of a transnational Church could not take sides. One main diplomatic objective of Benedict XV and Gasparri was to keep Italy out of the war. Besides meaning more bloodshed, Italy’s entry would also mean even more isolation for the Vatican.

Yet, the secret Treaty of London between the British, French and Italians, signed in April 1915, led to Italy’s participation in the war the following month. Included in the treaty, was a clause that excluded the Vatican from the future peace conference as the Italian government had become aware that the Vatican intended to be present at such a conference. Unfortunately for the Triple Entente powers, Benedict XV and Gasparri soon found out and this would have serious consequences in the triangular relations between the Vatican, Britain and nationalist Ireland. Benedict XV would not be another Leo XIII for Catholic Ireland.

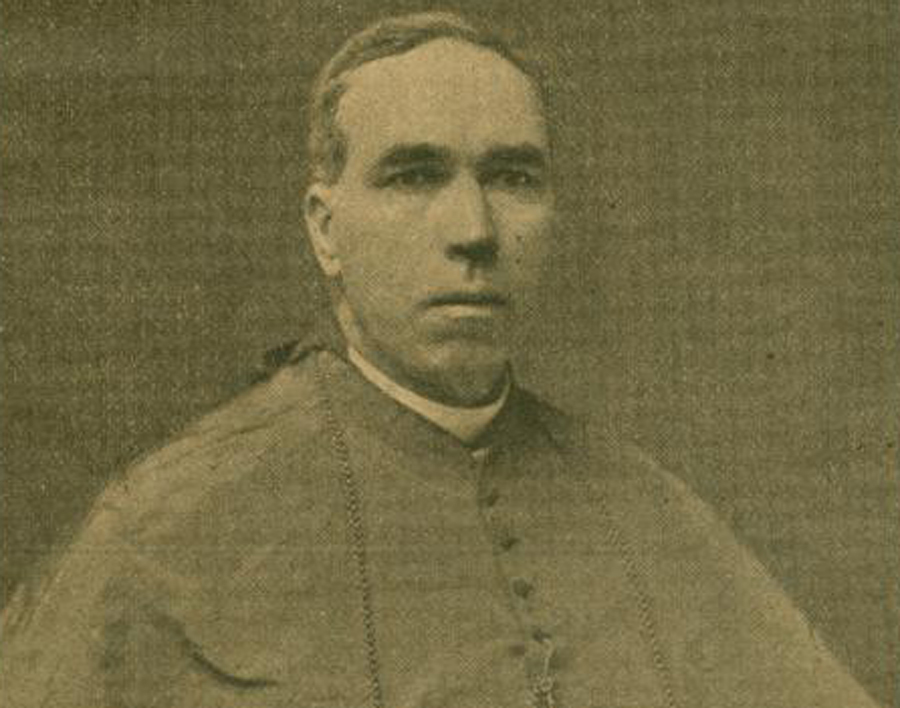

Michael Logue, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland (Image: New York Public Library)

The reaction of the Irish Catholic Church to the war was, broadly speaking, the same as elsewhere in Europe.

The overwhelming majority of bishops and priests were in favour of it, swept away by a wave of patriotism and nationalism. They justified the war on theological grounds as, to their minds, militaristic Germany had provoked it and it was a war for the freedom of small nations. What was remarkable was that the country had just been on the brink of civil war between nationalists (mostly Catholics) in favour of Home Rule and rejecting partition, and unionists (mostly Protestants) and concentrated in the northern province of Ulster, who bitterly opposed it. A last-minute compromise regarding Home Rule, which had been scheduled to be implemented in 1914, was found by British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s government. Home Rule was entered onto the statute book but its implementation was deferred until after the end of the war, which everybody believed would be soon. As to Ulster, a special solution was to be found.

The outbreak of the First World War had prevented a certain civil war in Ireland. As there was no conscription in the United Kingdom, the government relied on the motivation of men to volunteer for the army. The initial recruitment figures in Ireland were spectacular, considering the volatile Home Rule situation.

But from the summer of 1915 onwards, the numbers began to seriously decline as the horrors of trench warfare became known. The war was lasting longer than expected; Home Rule was not yet in sight; British recruitment operations were badly organised; and economic prosperity, engendered by the war effort, was undermining the motivation to enlist. The presence of priests on the recruitment platforms became less visible and fewer bishops sent supportive letters. Briefly put, the war was becoming unpopular and Ireland was hundreds of kilometres away from the frontline, both physically and mentally. For the Catholic Church it became vital to monitor the evolution of Irish public opinion towards the war, from John Redmond’s pro-war Home Rule party to anti-war groups and parties such as Sinn Féin.

In relation to the war, three Irish prelates stood out.

Cardinal Michael Logue of Armagh was in favour of the British war effort. Not being convinced of the sincerity of Asquith’s government concerning Home Rule and partition, however, he refused to actively support it. In the years previous, Archbishop William Walsh of Dublin had adopted a vow of political silence, deeming Redmond to be slavishly following the untrustworthy British Liberal Party. Behind the scenes, Walsh, ably helped by his secretary, Mgr. Michael Curran, did everything he could to sabotage the British war effort in his diocese.

It was Edward O’Dwyer, the Bishop of Limerick, however, who was the staunchest opponent of the war and the most vehement critic of Redmond’s pro-war policy.

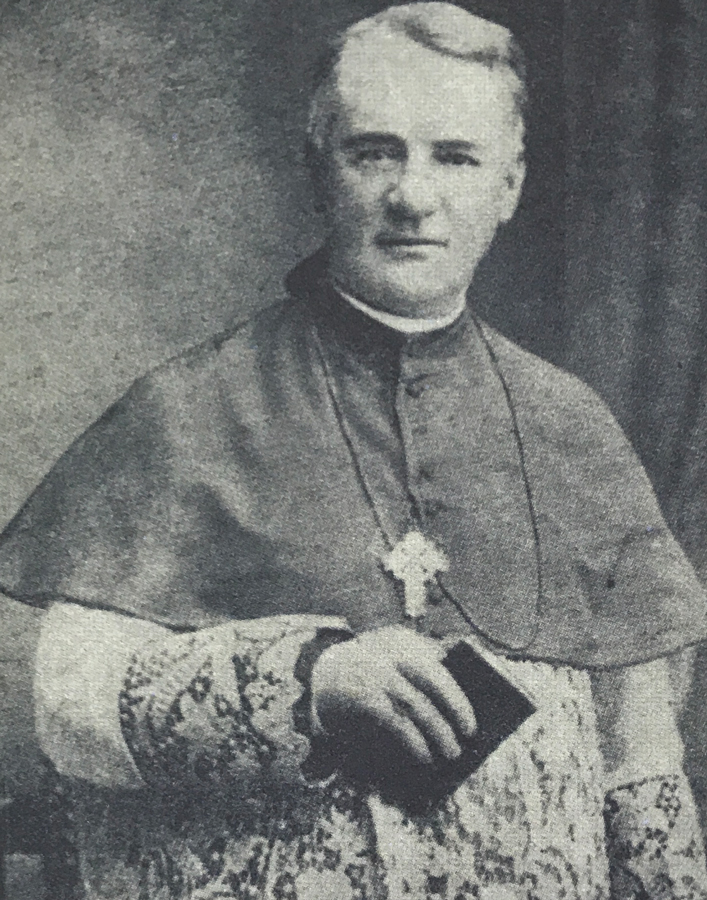

Bishop O'Dwyer (Image: The Capuchin Annual, 1966 - 1916 Rising Commemorative Pages. Courtesy of the Irish Capuchin Provincial Archives)

O’Dwyer was ultramontane in outlook, strongly believing in papal authority. Unlike the majority of Irish bishops, he followed Benedict XV’s peace policy and wrote eloquent letters in favour of peace and papal initiatives. In Rome, O’Dwyer’s anti-war activities were noticed by another Limerick man, Mgr Michael O’Riordan, the rector of the Irish College. O’Riordan was a nationalist but critical of some of Redmond’s policies, while the vice-rector, Mgr John Hagan, was more republican-minded. O’Riordan knew that the English community in Rome, notably Cardinal Aidan Gasquet, and occasional visiting English prelates like Cardinal Francis Bourne would probably try to influence the Pope concerning not only the war but British policy in Ireland as well.

When O’Dwyer published a very eloquent anti-war Lenten pastoral in February 1915, O’Riordan immediately grasped that there was a unique opportunity to translate the bishop’s letter into Italian and distribute it to Benedict XV and other members of the Curia and the Italian hierarchy. The letter was written by a bishop in a belligerent country who followed Vatican policy, and it was produced at a time when Benedict XV and Gasparri were trying to do everything they could to keep Italy out of the war. O’Riordan’s initiative was a resounding success, as O’Dwyer’s letter was circulated and used in dioceses across Italy. The Pope was pleased as it was excellent publicity for the Vatican.

O’Riordan would continue his translations of O’Dwyer’s letters until the bishop’s sudden death in August 1917. Benedict XV was much impressed. In February 1917, O’Dwyer wrote maybe his most eloquent anti-war pastoral. O’Riordan translated it and gave copies to the Pope and a number of important Italian cardinals. On that particular occasion, Benedict XV and Gasparri were full of praise, the Pope remarking: ‘[it was] the truth said with great accuracy and power’, adding ‘the man has brains’ (‘Quell’uomo ha una testa’).

O’Riordan also had regular audiences with Benedict XV to whom he explained the current political situation in Ireland from a nationalist point of view. The rector’s diplomatic initiatives paid off. Despite their official policy of neutrality, it was easy to guess where Benedict XV and Gasparri’s sympathy lay between a small Catholic Ireland and a powerful Protestant Britain. Under these circumstances, prelates such as Gasquet, Bourne, and the British Mission led by Sir Henry Howard and later Count de Salis had not much hope of influencing the Pope in favour of British policy. The Easter Rising of April 1916 was further evidence of this.

On 4 March 1916, Benedict XV wrote to a cardinal that ‘this war … appears to us as the suicide of civilised Europe’, an expression he would use again in his peace note of August 1917. On approximately 8 April (exact date unknown), he granted an audience to Count George Plunkett, a papal knight. Plunkett had been sent by the Irish republican leadership to inform him of the rising against the British planned for that Easter.

Count George Plunkett (Image: National Library of Ireland)

The idea behind his mission was to neutralise the expected condemnations of the Irish hierarchy by showing the Pope that the planned rising was theologically justified and by obtaining his blessing for it. Only Plunkett’s version of events is available and a degree of caution is necessary as his version cannot be confirmed by other sources. According to the Count, the Pope was well informed about Irish affairs, which confirmed O’Riordan’s successful diplomatic initiatives. The audience lasted two hours and nobody else was present. Plunkett gave him a letter written in French in which the republicans outlined their thinking to prove that the rising was theologically justified. Some parts were hopelessly, or intentionally, exaggerated, notably the chances of military success, a crucial theological argument for justifying a rising. The exact date of the rising was mentioned (then Sunday 23 April) as was Germany’s support. The Count asked Benedict XV to bless the rising, which he refused to do, but claimed that he did bless the republicans who would participate in it. The nuance is important; it meant that the Pope might not have been in agreement with the planned rising but that he knew, nonetheless, that it could not be prevented.

The Easter Rising began on 24 April and can be seen as a failure as it was not supported by the population while German support had not exactly been strong.

Circumstances would change when its leaders were executed by the British army, turning them into martyrs for the Irish cause. In Rome, O’Riordan had anticipated that the British would move against Irish nationalism. He set out to write a document explaining Britain’s poor management of Ireland and the inevitable rising that followed. It became known as the “Red Book” and created a sensation in Roman society. Cardinals asked for more copies. In Paris, a French diplomat who followed Irish affairs wrote that O’Riordan and Hagan had committed ‘real acts of treason’, had ‘direct and clandestine access to the Pope’, and ‘according to Cardinal Gasquet, they have a real influence over him’. In December 1916, the British Mission to the Vatican advised Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour not to insist with asking the Vatican to remove the rector and vice-rector of the Irish College or to neutralise them as it would not succeed.

The end of the war brought no changes to the rapprochement between nationalist Ireland and the Vatican set in motion largely by the leadership of the Irish College in Rome.

In April 1918, Prime Minister David Lloyd George made the disastrous decision to introduce conscription in Ireland, despite sound advice to the contrary. Immediately, the country mobilised to defeat his plan. The Irish hierarchy, ably led by Archbishop Walsh on this occasion, declared conscription to be ‘an oppressive and inhuman law, which the Irish people have a right to resist by all the means that are consonant with the law of God’. The intervention of the hierarchy gave moral guidance to the anti-conscription movement and avoided certain bloodshed. In all parishes, the clergy played a leading role in organising resistance. Lloyd George’s government was swiftly defeated. The conscription crisis signalled the beginning of the end of British domination in Ireland and had more drastic political consequences than the Easter Rising. But it was too much to swallow for the humiliated cabinet. Balfour had prepared a list of 26 priests who had, in his eyes, gone too far in their opposition to conscription and demanded disciplinary action by the Vatican. Cardinal Logue was offended as it reminded him of similar British approaches during the Plan of Campaign days back in the late 1880s when Balfour was then in charge of Ireland. In Rome, O’Riordan prepared the defence of the priests and met with influential members of the Roman Curia. In July 1918, the rector had an audience with the Pope. Benedict XV told him that he was very satisfied with the letter that the Irish hierarchy had recently sent him about the current problems in Ireland and the infamous Treaty of London of 1915, which the Bolsheviks in Russia had recently made public. O’Riordan subsequently contacted the Irish hierarchy to say that they had nothing to fear from the Vatican. Indeed, Gasparri informed the British Mission in diplomatic terms that he would let the matter rest. In plain terms, the Vatican had just rebuffed the British government.

Archbishop William Walsh (Image: National Library of Ireland, PD WALS-WIL (1) IV)

In Ireland, Sinn Féin, the party which had consistently opposed Ireland’s participation in the war and was now led by Éamon de Valera, had won the general election in December 1918 and wanted to participate in the Paris Peace Conference in Paris.

But Ireland, like the Vatican, came nowhere near the negotiating table, despite the fact that a Sinn Féin delegation led by Seán T. O’Kelly and George Gavan Duffy was in Paris, trying to approach the Big Three (Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and Wilson). It quickly became apparent that self-determination was for small nationalities of the defeated great powers, not the victorious ones. Wilson refused to commit himself to self-determination for Ireland despite the increasing pressure of the Irish-American community and leading Irish-American members of the hierarchy. Interestingly, during the peace conference, French naval intelligence obtained information that Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore had advised the Vatican not to hinder the initiatives in favour of Ireland taken by the (American) Irish Race Convention.

The French agents also learnt that ‘the German government had recently asked the Vatican to stop supporting Irish insurgents in order [for Berlin] to prepare a rapprochement between England and Germany’. Although the source of this information remains unknown, it fits with the general pro-Irish attitude of the Vatican that had developed during the war.

The aftermath of the First World War was a troubled period for Ireland, just as it was the case with other countries in Central and Eastern Europe.

The War of Independence began in 1919 and ended in 1921. It was followed by a bitter civil war between 1922 and 1923 when Irish republicans split over the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The Treaty established an Irish Free State, not a republic, and in-effect confirmed partition, since Northern Ireland had begun to function as a separate polity in 1921.

The Vatican did not interfere during the War of Independence and adopted a cautious attitude during the Civil War, essentially not wanting to take sides between pro and anti-Treatyites. When the political situation normalised, Gasparri and Joseph Walshe, the secretary for external affairs of the Free State government, agreed that official diplomatic relations between the two states should be established.

This would not take place until 1929. Some members of the Irish hierarchy were still reluctant to see the arrival of a papal nuncio. Benedict XV, a pro-Irish Pope, died in January 1922. Cardinal Pietro Gasparri continued as secretary of state under Pius XI. Mgr Michael O’Riordan died in 1919. All three men had laid the foundations of new relations between the Vatican and Ireland in the First World War and its aftermath, during which the Irish revolution unfolded.

Dr Jérôme aan de Wiel is lecturer in history at University College Cork.