The Royal Irish Constabulary and Colonial Policing: Lessons and Legacies

By Dr Seán William Gannon

On 27 August 1920, the RIC’s in-house propaganda freesheet, the Weekly Summary, warned that the newly-recruited Black and Tans (who had been arriving in Ireland since January) would make the country ‘an appropriate hell for those whose trade is agitation and whose method is murder’, and the orgy of reprisals against republicans and their communities that followed demonstrated that this was no idle threat. While reprisals had been hitherto an occasional feature of the police counterinsurgency (the burning of Tuam in late July the most significant example), they now assumed the status of a tactical constant as ‘old RIC’, Black and Tans, and Auxiliaries, acting variously or in concert, took increasing recourse to communal retaliation for IRA attacks. Extensive written and photographic reportage of reprisals such as Galway (8 September), Balbriggan (20 September), Trim (27 September), Mallow (29 September), Granard (4 November), and Cork (11/12 December) so appalled British public opinion that, by spring 1921, journalist Henry Woodd Nevinson could write that ‘at last the feeling of our country is, I think, [fully] awake to the hideousness of this hellish policy’. Thus, Britain lost the propaganda war critical to its counterinsurgency’s success.

Police reprisals also scuppered any possibility that the RIC could be retained as part of the December 1921 peace and it was disbanded between January and August 1922. However, its transnational influence on the British Empire’s policing, ongoing since the mid-19th century, survived its disbandment. This was particularly true in the so-called ‘dependent’ or ‘colonial’ empire’ (viz. those territories governed through London, as distinct from the self-governing dominions), the ‘colonial police’ forces of which, like the RIC, constituted the primary agents of everyday imperial power and the state’s principal coercive arm during times of anticolonial resistance and/or public unrest. This essay explores the RIC’s colonial ‘afterlife’, with particular focus on the Palestine Mandate, to where hundreds of disbanded Irish policemen immediately transferred.

The international notoriety to which the ‘hellish policy’ of Irish police reprisals gave rise rendered highly controversial the reemployment of disbanded RIC, particularly in policing roles. The police forces of the fledgling Irish Free State certainly provided cold houses. In May 1922, a mutiny by members of its new Civic Guard forced the removal of former RIC officers appointed to senior positions while just 2% of those recruited into its successor force, An Garda Síochána, had seen RIC service. With the exception of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, which recruited over 1,300 ex-RIC between June and October 1922, the UK’s ‘home constabularies’ also proved extremely reluctant to accept applications, fearing the effects of large-scale recruitment from an essentially paramilitarized and discredited ‘Black and Tan’ force. Most significantly, London Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir William Horwood rejected a request to take on disbanded members, partly because their Irish service was, ‘even previous to Sinn Féin activities ... more of a military nature than that of a civilian police force’. Similarly, in the dominions, local constabularies were unwilling to recruit ex-RIC on account of what historian Kent Fedorowich described as ‘the sheer nature of the violence and the role played by the Black and Tans … [which] conjured up scenes of barbarity and brutality [with] which no dominion police force wanted to be associated’.

The ‘colonial police’ forces of Britain’s dependent empire did not share such qualms, for they had longstanding transnational relationships with the RIC. It had proved attractive to 19-century colonial governments, which saw in its central control, semi-military character, and coercive function a more suitable model for colonial conditions than the localized, politically independent, and purely civilian police services of Great Britain. Consequently, most colonial forces used the RIC as an institutional template and recruited RIC personnel at gazetted and superior non-gazetted rank, establishing the ‘Old Force’ as what one senior Colonial Office official, Sir Charles Jeffries, described as ‘the really effective influence on the development of the colonial police forces during the nineteenth century’. In 1843, for example, Sir Charles Napier, the Anglo-Irish governor of the newly annexed Indian province of Sind, established its police force along RIC lines, and several RIC personnel were seconded to assist him in so doing. Other governors gradually followed suit and the 1861 Police Act, which standardized policing across much of the Raj, was modelled on the Irish example. Policing in the British Caribbean was similarly RIC-influenced. This was especially true of Trinidad and Jamaica, the constabularies of which were directly modelled on the RIC and into which dozens of ex-RIC were recruited in the 1880s and 1890s to boost their military efficiency in dealing with political/popular unrest. RIC personnel were also used as ‘trouble-shooters’ in British Guiana: three officers were sent to reform its failing police force in 1884, signalling the start of its rapid reorganization along RIC lines. And while Britain’s ‘East Africa’ and ‘Far East’ police forces were not explicitly RIC-modelled, they were ‘stiffened with an RIC backbone’ through Irish recruitment at gazetted and NCO rank. The transnational transmission of RIC influence was compounded by the training of colonial police officers and selected NCOs at the RIC’s Phoenix Park Depot: in excess of 160 had attended by 1915, receiving instruction in a range of subjects, including musketry and military drill.

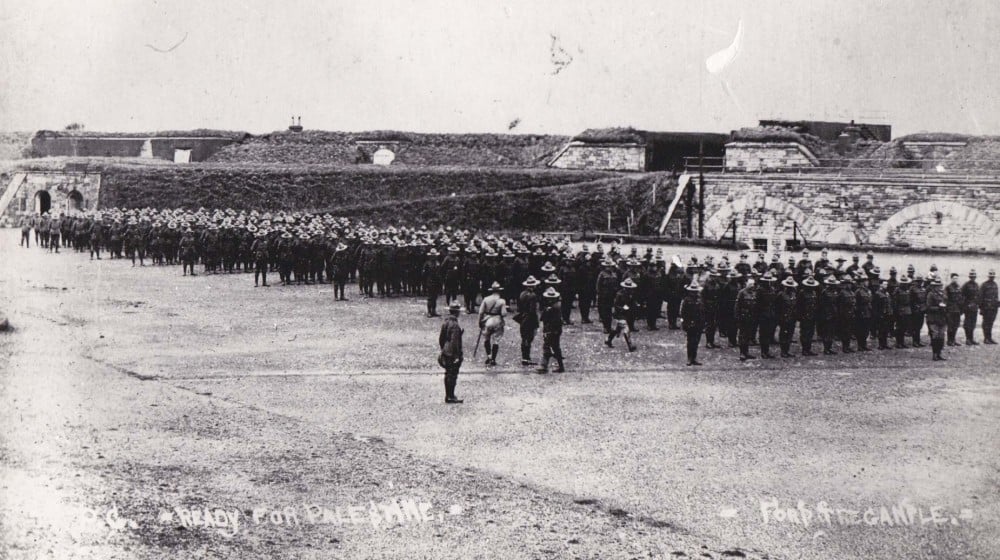

‘Ready for Palestine’: members of the British Gendarmerie at Devonport

The hybrid civilian/semi-military identity that colonial police forces and the RIC shared meant that most were happy to recruit from the ‘Old Force’ during the Irish War of Independence and aftermath. For instance, in summer 1921, when the RIC’s reputation was at its nadir, Jamaica requested the recruitment of an inspector and two staff-sergeants-major from its ranks and, six months later, Trinidad circulated a call for a sub-inspector in the Phoenix Park Depot. Colonial recruitment continued in 1922. The India Office, for example, sought to recruit ex-RIC as police, considering them ‘tactful – and painfully experienced – in handling crowds’; it did attempt to exclude Black and Tans, but only because their recruitment would prove controversial. Meanwhile in April 1922, over 700 disbanded RIC transferred to Palestine as the British Section of the Palestine Gendarmerie, a striking force/riot squad formed through the agency of RIC chief, Major-General Henry Tudor, to reinforce the locally recruited policing forces. The great majority were former Black and Tans and Auxiliaries, something which the British and Palestine governments schemed (unsuccessfully) to obscure.

This British Gendarmerie was, not just overwhelmingly RIC-manned, but explicitly RIC-modelled. For example, its structure and distribution followed that of the Auxiliary Division, comprising a headquarters’ unit and six 100-strong urban-based companies which patrolled the surrounding countryside. It was also barracked, equipped, and armed like the RIC, and its training followed the RIC code, with a heavy emphasis on physical and military drill. Most importantly, it functioned as an Auxiliary Division-style mobile paramilitary crack squad which operated as an emergency reserve to assist Palestine’s locally recruited policing forces in the maintenance of public order and the fight against brigandage, viz. highway robbery and raiding by armed bands which presented a persistent regional problem in the late Ottoman period. Both duties cast the British Gendarmerie as a counterinsurgency force. Almost all civil disturbances in 1920s Palestine were manifestations of anti-Zionist protest and, by the time the force was deployed in April 1922, they gave the appearance of a proto-insurgency. The same was true of brigandage which, while seldom consciously anti-colonial, had so begun to resemble ‘social banditry’ by this time that the Palestine government warned of a ‘resuscitation of Political Brigandage, in connection with recent developments in the political situation’. Even Tudor (who assumed the role of Palestine’s joint general officer commanding and director of public security in June 1922) recognized its anticolonial subtexts, partly ascribing the increase in highway attacks on Europeans in August to ‘the general animosity against the Palestine Government roused amongst the Arab population by political agitation’ and remarking sourly to Palestine’s attorney-general that British Gendarmerie personnel ‘had to leave Ireland because of the principle of Irish self-determination and were sent to Palestine to resist the Arab attempt at self-determination’.

Although Britain had, to all intents and purposes, deployed another Auxiliary Division in Palestine, lessons from Ireland were certainly learned. For example, the British Gendarmerie was more timely deployed than its Irish equivalent had been. Mindful that the unsystematic character of IRA operations in 1919 had masked the emergence of a concerted military campaign, the erratic, uncoordinated Arab violence of 1920/21 was treated as an inchoate insurgency which the British Gendarmerie was, through early (and robust) intervention, quick to suppress. Furthermore, force discipline was, under the direction of Commandant Angus McNeill, far more rigidly imposed than it had been in Ireland. Determined that what one of his staff sergeants termed ‘the Irish way of things’ would not prevail in the British Gendarmerie, he quickly curtailed initial problems with (mainly) alcohol-related indiscipline with fines, curfews, and dismissals and, by the end of 1922, discipline was being variously described by those on the ground as ‘very good’, ‘very high’, and ‘excellent’. This was confirmed by the dismissal rate which, at 2% annually, compared very favourably with that amongst the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries which Bill Lowe estimated at 4.7%, rising to almost 7% if including those recorded under what he termed ‘the ambiguous category discharged’. Significantly, the British Gendarmerie did not adopt the reprisals policy that came to define policing in later revolutionary Ireland. Its employment of lethal force against ‘brigands’ did echo the strategy adopted against Irish guerrillas. However, retaliation for attacks on the British Gendarmerie targeted the perpetrators alone and, even in cases where gendarmes were killed, revenge was not wreaked on the wider Arab population. However, this lack of recourse to reprisals largely derived from the fact that ex-RIC operated in a very different environment in Palestine. Their timely deployment ensured that the anti-Zionist violence of 1919/21 did not escalate into full-scale insurgency, and they were unchallenged by the outbreaks that did occur, their capacity to suppress them never in doubt. Nor were they a primary target; these outbreaks were inter or intra-communal and not then directed against imperial rule. Therefore, the stresses and strains under which these men had laboured in Ireland were absent in Palestine: Tudor himself described the country as ‘a rest cure after Ireland’. That the British Gendarmerie would likely have behaved very differently had it found itself the focus of an IRA-type insurgency was indicated by McNeill’s recommendation for quelling the Great Arab Revolt of 1936/39 when anticolonial resistance took the form of a large-scale insurgency: ‘I should try to spread terror in the land … you would only have to be really brutal and bloodthirsty for about a month and [the Arabs] would be eating out of your hand’.

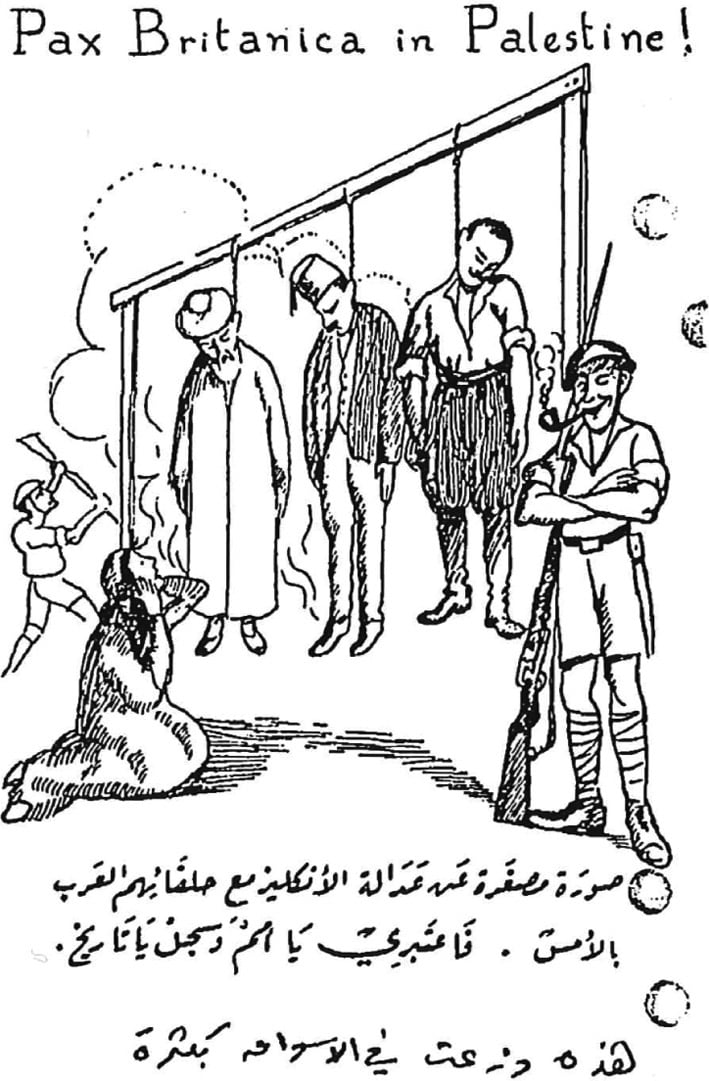

Arab Revolt-era handbill on ‘Pax Britannica’ in Palestine. Click image to enlarge

The British Gendarmerie was itself long defunct by this time, disbanded in April 1926 following a reorganisation of the garrison in light of the peaceable state of the country. It was replaced by a new ‘British Section’ attached to the Palestine Police (BSPP), a 220-strong crack squad was intended to stiffen the main locally recruited body of the force. Just under 100 of its original draft were former gendarmes, 72 of these ex-RIC. Force strength was increased in response to emergent threats to public security; it was increased to over 600 in the wake of anti-Zionist riots in 1929, to 2,800 during the Arab Revolt, and to well over 4,000 in 1945/47 to meet the challenges of the intensifying Zionist insurgency against British rule. That the police response to these anticolonial insurgencies was informed by the experience of Ireland is today an historical commonplace. However, the BSPP’s counterinsurgencies were largely devised and driven by ‘non-RIC’ officers or external advisors and typified the lessons of Ireland unlearned. Take, for example, the Arab Revolt. Like Dublin Castle in 1919, the Palestine Government did not conceptualize the initial outbreak of violence in spring/summer 1936 as anticolonial, but rather a crime wave which the police were sent out to put down. However, the BSPP had since 1930 undergone a process of ‘civilianization’ which saw training refocussed from military drill and gendarmerie duties to policing procedure, investigation, languages, and law. Hence, it proved entirely ill-suited to and ill-equipped for counterinsurgency, defaulting to a policy of brutal ‘Black and Tan’-type coercion which, as in the case of the ‘domesticated’ RIC before it, was a testament to force weakness rather than force strength. As in Ireland, a ‘police advisor’ was installed from outside, in Palestine imperial ‘counter-terrorism expert’ (and Irishman) Sir Charles Tegart, who was contracted in 1937 to overhaul the BSPP for the fight. He adopted a thoroughly ‘Irish’ approach, the centrepiece of which was reinforcement through the recruitment of ex-servicemen. Warning that ‘gangs of banditry armed with rifles cannot be dealt with by policemen with notebooks’, Tegart recommended an influx of ‘the tough type of man’ who was capable of ‘the rough work of a quasi-military kind that has to be done in times of disorder’ and over 1,800 were quickly obtained. However, as in Ireland, this mass recruitment of what Palestine’s high commissioner Sir Harold MacMichael described as ‘in effect ex-soldiers dressed in police uniform’, fielded with minimal police training, served only to further undermine force efficiency and intensify the prevailing coercive approach. By autumn 1938, MacMichael was himself noting ‘occasional … black and tan tendencies’ in the BSPP which, as in Ireland, centred on collective reprisals for attacks on police. In Palestine, these reprisals included the wanton destruction of Arab homes, livestock and crops, and beatings and extra-judicial killings, including summary executions and shootings ‘while trying to escape’.

As in the RIC’s case, the tactical futility of the BSPP counterinsurgency resulted in increasing British Army involvement which in Palestine culminated in the military’s assumption of full operational control in September 1938. But, notwithstanding the repetition of the errors of Ireland, the Arab Revolt was eventually effectively crushed. For the British Army’s approach was itself so frequently savage that it was accused of operating a ‘Black and Tan regime’, while the placing of the BSPP under its aegis removed any residual restraint that civil policing conventions imposed. In a faraway land of which Britons knew little, the state violence routinely employed was not subjected to Ireland-style press and political scrutiny. Furthermore, it could be applied to a non-white ‘colonial race’ in a manner unthinkable in ‘metropolitan’ confines. Former Black and Tan, British Gendarmerie constable, and BSPP inspector Douglas V. Duff used an exchange between a BSPP officer with an RIC pedigree and a British visitor to Palestine to encapsulate this type of thinking:

- [The Arab insurgents] are nothing but a gang of toughs, looting and killing for what they can make out of it. They’re not patriots, they’re criminals …

- Some of the men who were hanged during the [Irish] Troubles were condemned as criminals. Kevin Barry and the rest.

- That’s different. They were white men.

The BSPP came to replace the RIC as the principal recruitment and training ground for officers and NCOs for other colonial police forces: between 1933 and 1950, in excess of 2,500 BSPP personnel transferred to policing positions in other parts of the dependent empire, several of them ex-RIC. David Anderson and David Killingray have suggested that ‘this movement of individual [RIC] officers, even of junior rank, may have had more direct influence upon policing practise than any accumulated process of learning achieved by senior commanders and applied to colonial policing as a matter of policy’ while Matthew Hughes posits a ‘transfer of an institutional memory’ from Ireland to the wider empire. Yet, the extent to which approaches to police counterinsurgency in territories such as Malaya, Kenya, and Cyprus were informed by the experience of revolutionary Ireland has yet to be properly evidentially assessed. Moreover, arguments for an RIC influence in these theatres essentially stand on the premise that Palestine served as its conduit (indeed, Anderson and Killingray consider the Palestine Police the ‘most notable’ and ‘perhaps the most notorious’ example of an imported Irish ethos), and there the RIC’s legacies were complex and, at times, contradictory.

Dr Seán William Gannon is a historian of 20th century Ireland, the British Empire, and their intersections. His book, The Irish Imperial Service: Policing Palestine and Administering the Empire, 1922-1966 is published by Palgrave Macmillan.