The MP for Ireland: Laurence Ginnell and 1916

by Paul Hughes

It is 11 May 1916. Dublin is in ruins, and 13 men have, so far, been shot by firing squad for their prominent roles in the Easter Rising. Thousands more have been, or will be, rounded up, deported and imprisoned.

Already, London’s response to what was, at the outset, an unpopular rebellion, had fostered a growing respect for the rebels. Even the constitutional nationalists in John Redmond’s Irish Party – who had previously looked upon the revolutionaries as wreckers and miscreants – began to wobble, as their relevance faded in the midst of such polarising slaughter.

On 11 May, John Dillon, one of the Party’s top brass, made a lengthy speech in the House of Commons arguing for leniency in Ireland. He declared that in spite of his belief that the rebellion was ‘wrong’, the fact that it had been ‘drowned in a sea of blood’ would have lasting consequences for the relevance of mainstream, constitutional Irish politics, and the Irish Party’s Home Rule project.

Dillon’s speech, delivered 24 hours before British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith departed for Ireland to assess the military’s ongoing response, is widely credited with applying the necessary pressure on Asquith to call a halt to the executions and secret military tribunals.

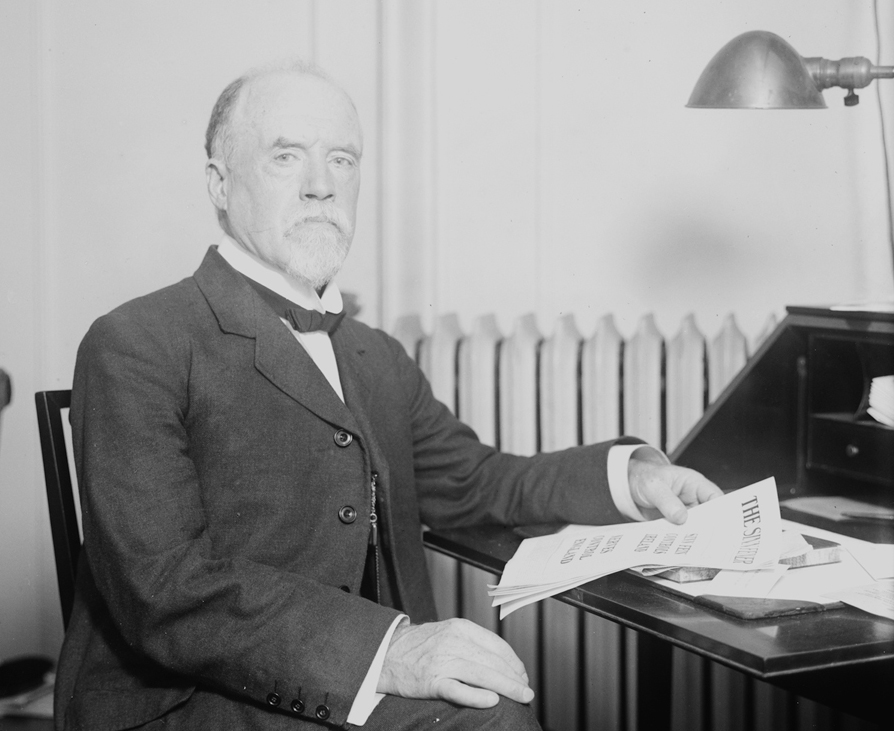

But one man’s parliamentary campaign has been all but forgotten by historians. Laurence Ginnell (1852-1923) – the maverick independent nationalist M.P. for North Westmeath – was out of the traps long before Dillon and his colleagues displayed any sort of odium towards British policy.

Ginnell, a native of Delvin, Co. Westmeath, was the solitary and often abrasive voice of the nationalist ‘other’ in Parliament. Since 1911 – two years after he split with the Irish Party – he harried and hassled successive British Cabinets and officialdom on a range of topics as diverse as women’s suffrage and the scandal-ridden 1907 theft of the Irish Crown Jewels. As the leader of the 1906-9 Ranch War, and a pioneer of political cattle-driving, he was also the undisputed critic in Parliament of the notion that the Irish land question had in any way been satisfactorily settled.

But it was his agitation against Irish involvement in World War I which catapulted Ginnell to international notoriety. In Parliament, he campaigned vigorously against British army recruiting in Ireland, and against the imposition in this country of the wartime Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), which resulted in deportations, proscribed meetings and the suppression of nationalist newspapers. Indeed, in 1915, his parliamentary protests narrated an implosion in army recruiting numbers in Ireland.

Ginnell’s anti-war enquiries went right to the heart of the British establishment. So much so, that in June 1915, the nominal leader of the Conservative Party and Secretary of State for the Colonies, Andrew Bonar Law, considered resigning when Ginnell learned of the Canadian’s compromising connections to a Scottish steel firm, which had been found guilty of selling munitions to Germany. Only the intervention of Asquith, who viewed Ginnell as a ‘maniac’, stopped Bonar Law from quitting the fragile Liberal-led coalition.

At the outset of 1916, then, Ginnell’s agitations were taken very seriously by those in power – to the extent that after the Easter Rising, Dublin Castle intelligence chief Major Ivor Price was keen to pin Ginnell down as a ringleader in the revolutionary conspiracy. He was spared from interrogation and imprisonment, perhaps, by the testimony of Irish Volunteer chief of staff Eoin MacNeill, who told Price that Ginnell merely ‘asked questions’ on their behalf.

The reality was that Ginnell and his wife Alice – a member of Cumann na mBan's London branch since 1915 – were much more connected to the revolutionary underground than MacNeill either knew or let on. His relationship, as a non-member, with the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Arthur Griffith-led Sinn Féin stretched back to 1906, when he first befriended the IRB organiser Bulmer Hobson at a ‘Myles the Slasher’ commemoration in Finea.

Laurence Ginnell and his wife Alice roomed with Constance Markievicz when in Rathmines, one antecdote claims the 'Irish Republic' flag hoisted over the GPO was fashioned by the rebel countess using Ginnell’s green bedspread. (Image: National Museum of Ireland)

In 1911, he shared a platform with Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, Constance Markievicz, Major John MacBride and other leading 1916 commandants in opposition to King George V’s visit to Ireland. When not in London, the Ginnells roomed with Markievicz at her home in Rathmines, with one anecdote claiming that the ‘Irish Republic’ flag hoisted over the GPO was fashioned by the rebel countess using Ginnell’s green bedspread.

When the Rising erupted in Dublin, Ginnell was in Mullingar making his way back to the House of Commons via Dublin. The taxi in which he travelled with the Dublin wit, Oliver St John Gogarty, was shot at by Irish Volunteer sentries at Cabra, who were keeping an eye out for British officers; far from being angered, Ginnell hopped out of the car and embraced the rebels. Though he believed that the revolutionaries should have waited to act until the imposition of conscription – at which point, he believed, they would have had the entire country behind them – Ginnell nevertheless respected the rebellion as a valid statement of Irish national aspirations.

On 3 May, Ginnell was in the Gaelic League’s London office when he heard that his close friend, Volunteer officer and fellow Gaelic Leaguer The O’Rahilly, was dead, that Dublin was in ruins, and that the first executions had taken place. He wept bitterly. When Asquith formally announced the executions of Patrick Pearse, Thomas Clarke and Thomas MacDonagh in Parliament, Ginnell loudly denounced the British Cabinet as ‘Huns’. His claim that members of the Irish Party cheered the news of the executions – one vigorously denied by the Redmondites – stuck like dried mud, and became a rallying cry for Sinn Féin as it gradually triumphed over the Party after 1916.

In Parliament, he was relentless. He accused Asquith of ‘murder’, and bombarded the Cabinet with questions about prison conditions, the nature of the secret courts-martial, and about the welfare and status of individuals arrested in the Rising’s aftermath.

A pamphlet featuring Laurence Ginnell’s House of Commons speech on 11 May 1916 was a staple of Sinn Féin propaganda in 1917. (Image: Courtesy of the Ginnell collection, Westmeath County Library, Mullingar.)

Like Dillon, Ginnell also made a lengthy speech in the House of Commons on 11 May. Heckled and laughed at by M.P.s on the English and Irish benches whom he viewed as ‘imperialists’, he told James Lowther, the Speaker of the House of Commons: ‘The murder of my friends is not a becoming subject for the Speaker... to smile at’.

Accusing Dillon and the Irish Party of trying to ‘whitewash’ themselves and the departing Chief Secretary for Ireland, Augustine Birrell, Ginnell railed against British ‘atrocities’ in Dublin. Claiming that 50 men had been summarily shot in the Royal Barracks after Easter Week, he charged the British with pursuing genocide in Ireland. ‘You want to wipe out the Celtic race,’ he said, referring to the Famine. ‘As the Times boasted 60 years ago: “The Celt has gone, gone with a vengeance.” No, by God, we are here still, and before you are done with the Celt you will have something more creditable to do than laughing, and making a mockery of brave men who sacrificed their lives in the noblest cause for which men can die or fight.’

‘Success,’ he told the Commons, ‘is the one thing that commands universal approval of revolutions. Had this one been successful, those heroes whom you shot down in cold blood would have been real heroes, living and ruling the country at the present time, instead of being in their graves.’

The next day, Asquith travelled to Dublin and compelled the architect of martial law in Ireland, General Sir John Maxwell, to call off the executions and military tribunals. This was not before two more Rising commandants were shot: Seán Mac Diarmada and James Connolly. On the night before his death, Connolly’s daughter Nora told him of Ginnell’s exertions on their behalf. ‘Good man Larry,’ Connolly said. ‘He can always be depended on.’

Jailed in 1907 for encouraging cattle driving, Ginnell was no stranger to British political imprisonment practices, and in the summer of 1916, used his credentials as an M.P. to gain access to and inspect jails holding incarcerated republicans.

He quickly became the object of much affection among the prisoners, advocating on their behalf in Parliament, and becoming a channel for contact between them and their families.

Westmeath man Tomás Malone, who was jailed at Wandsworth, told the Bureau of Military History: ‘He used wear a swallow-tail coat and he would get the crowd around him in a ring. He would whisper “Search the coat now, boys”... and we knew how to get at the tail pocket of the coat. He would have it full of cigarettes, matches and tobacco and... we would dump whatever letters we had into his coat. He took notes of our complaints and did them in his usual shorthand’.

On foot of this, Ginnell became known among internees as ‘the G.P.O.’, and in one instance, prison officers complained that he made a speech so seditious that it prompted jubilant prisoners to parade him around the grounds on their shoulders.

When the authorities put a stop to his prison access in July 1916, he tried to gain entry to Knutsford Detention Centre in Cheshire by signing his name in Irish, resulting in his arrest and a widely publicised court case, for which his defence was funded by the Gaelic League. Refusing to pay the resultant fine, he willingly served a brief spell in prison, sealing his own reputation as a 1916 prisoner.

Prof. Michael Laffan, UCD, explains how the Easter Rising gave the Sinn Féin party the momentum to become the biggest party in the country by 1918.

In the political vacuum between the Rising and the 1918 general election, Ginnell became what one American journalist called one of the ‘most talked about’ political figures in either Britain or Ireland. Later in 1916, he pleaded with leading members of the clergy to encourage them to turn their backs on the Irish Party, and in the meantime, shepherded the anti-partitionist Irish Nation League through its eventual incorporation into Sinn Féin. A key figure in Count George Noble Plunkett’s successful North Roscommon by-election campaign in 1917, by July of that year Ginnell had himself left the House of Commons to join the new movement in Ireland. He was later elected to the First Dáil, in which he served as Director of Propaganda.

Between 1915 and 1918, Ginnell was at the apogee of his power and influence in Ireland. But not long after his former friends in the Irish Party faded from prominence, his own career went into his decline. The best part of two years in prison for ‘unlawful assembly’ and inciting cattle-drives took its toll on him, and in 1920, the 68 year old was forced to leave the country for the good of his health.

Highly respected in Irish-American circles, Ginnell went to Chicago to carry out propaganda work on behalf of the Dáil, before continuing to Argentina as the Republic's first accredited envoy in South America (August 1921).

An opponent of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, he died in Washington, D.C. in April 1923 while pressing the anti-Treaty cause there.

– Paul Hughes is a Mullingar-based journalist and a PhD student at Queen's University, Belfast