The Lady and the V.C.

Lady Gregory, Yeats, Shaw and the recruitment play that was too dangerous for Ireland at wartime.

By Ed Mulhall

The lady is writing at her desk. The April sun is framing her through the drawing room window. At this desk folk tales were transcribed, sagas and plays written, tales of Cúchulain and Lir, a tradition established. Here too, she wrote a diary of her day and a correspondence that knitted together the great personalities of the Irish Revival. Their books are on the shelves in this room. Here, too, are the latest art gallery catalogues given to her only the previous week. Elsewhere in the house a great painter is reluctantly creating portraits of her grandchildren. On the desk are mementoes of her travels, behind her the tall white marble statue of the Venus de Medici standing in the bow window. But as well as being a writer and a leader of a cultural movement she is also a mother, a grandmother and in charge of this great house and lands. As the photograph is taken, the lady is not writing another play or story but tending to the duties of the household, writing a reference for a kitchen maid. The house is Coole. The lady is Augusta Gregory. The photographer is George Bernard Shaw. It is April 1915, the world is at war and these two writers are at the centre of a great cultural movement, seeking connection, collaboration and support, often in these rooms or within the correspondence originating here, and finding expression in Dublin, London and across the literary world. Even then, as the photograph was being taken, they were discussing another work, one of this time and this place, which would address the major issue of the day, whether or not to fight in the war then raging across Europe. And what that war and the perils it brought would soon bring home.

Lady Isabella Augusta Gregory, co-founder and director of the Abbey Theatre, Dublin. (Image: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

The desk was her late husband’s, bought in London, on which he wrote his own autobiography. Busts in white marble of his father and mother were also in this room as was another large figure of Andromeda by Canova which was 'carried through Italy on ox carts and brought in a ship to Galway'. There too silhouettes, miniatures and portraits of the family down the ages. There were no books in this room when she arrived there; the house had its own impressive library. But she changed ‘its tradition of idle elegance by letting in the tide of printing ink’. The choice was therefore very selective, very much her own. Firstly, women writers, Susan Ferrier, France Burney, George Eliot, Mrs Gaskell, Jane Austen, Emily Lawless, Martin Ross and all by the Bronte sisters. Then in one white glass fronted case were displayed the books given to her by her friends. All of W.B. Yeats’ books apart from the very earliest, the poems of William Blunt for whom she wrote love sonnets, books by Æ, Edward Martyn, Douglas Hyde, Kuno Meyer, Edward Bowen, John Mansfield, George Moore and J. M. Synge. There are books of her earlier life: Kinglake on the Crimea, Lady Anne Blunt on the Bedouins of the Euphrates, Alfred Lyall on India, J. G. Cordery on Homer and two of the books of Theodore Roosevelt given to her by the author, the former President of the United States.

On her desk is a silver box and ivory casket, from Ceylon, where she keeps mementoes of the children and grandchildren, as well as some precious documents, among them two old song books from 1798 and 1797 (The Martyrs of Liberty and Paddy's Resource) and a card in memory of William Orr which were 'found by Mr. Carleton in Lord Edward Fitzgerald’s apartment in Leinster House in 1798’.

A bible from 1658 is also there, inscribed: ‘Frances Barry, her book, 1710 and Frances Aigoin, her book, 1st January 1724/5’. To this Lady Gregory had added: ‘This book which had belonged to her Huguenot grandmother was given by Frances Persse to her daughter Augusta Gregory, March 1895.’ She had also written ‘William Robert Gregory, born May 20,1881 at 3 St George's Place London’ and in Robert’s writing are the birth dates of his children Richard, Anne and Catherine.

Some unfinished manuscripts lie nearby and one tiny collection of small books supported by two ebony Ceylon elephants. Here are Browning's Love Poems inscribed by the late painter J.D. Innes, Commera Swamy's dialogues of Gotama Buddha, an Elizabethan calendar for 1906, Fr. John Grey’s Blue Calendar, William Blunt’s Love Poems and the first edition of Chamber Music by James Joyce. Lady Gregory would later recall:

‘I knew him in those days and when he was leaving Ireland, going to Paris alone and friendless to try for a degree in Medicine there he wrote me: “for then I can build up my work securely. I want to achieve myself - little or great as I may be... I shall try myself against the powers of the world. All things are inconsistent except the faith in the soul, which changes all things and fills their inconsistency with light.”

He was then a handsome petulant boy. I believed in his genius though, alas I cannot follow him through those miry roads or rooms to which his genius has drawn him to write.’

On a table beside the desk are two letter books, treasured letters to her, amongst them ones from Thomas Hardy, Sargent, William Orpen, Sir John Lavery, George Moore, Æ, James Joyce, Galsworthy, Synge, Shaw, Mark Twain, Robert Browning and Oscar Wilde. On the walls of this room are two pictures of Venice described by Yeats:

‘…one a Canaletto that has little but careful drawing and not a very emotional pleasure in clear bright air, and a Franz Francken, where the blue water that in the other stirs one so little, can make one long to plunge into the green depth where a cloud shadow falls. Neither picture would move us at all if our thought did not rush out to the edges of our flesh and it is so with all good art, whether the Victory of Samothrace which reminds the soles of our feet of swiftness, or the Odyssey that would send us out under the salt wind, or the young horsemen on the Parthenon that seem happier than our boyhood ever was, and in our boyhood's way.’

Beside these a Poussin as Lady Gregory described: ‘a musician laurel wreathed turban, his eyes cast down as he walks meant, I think to represent Homer; and I have been used to call it Raftery after our own peasant poet who wandered through Ireland a hundred years ago “full of grace, full of love” through playing music to empty pockets.' The painting was a gift from her nephew Hugh Lane, the art collector and Director of the National Gallery and it was he who had given her the art catalogues, the last one signed 'from the director' and given to her on the steps of the Gallery just before he set off for America a few weeks earlier.

Lady Gregory had herself just returned from America, giving lectures to raise funds for the Abbey Theatre. She had spent the last two weeks of her visit with the lawyer and art patron John Quinn with whom she had had a brief affair two years before. He had insisted on her travelling home on an American liner, because of the dangerous seas, and gave her the first edition of Joseph Conrad’s Victory to read on the passage home. Robert Gregory was in Coole together with his wife Margaret and their children. George Bernard Shaw and his wife, Charlotte, arrived on 13 April and stayed until 9 May. Shaw was a close friend of Lady Gregory. He had spent Easter with Horace Plunkett, the founder of the Irish co-operative movement, and was at this time at the centre of a political storm in the aftermath of his pamphlet ‘Commonsense about the War’. There had been moves to have him removed from the society of authors, attempts to boycott his plays and numerous requests to give lectures and talks on the subject (including an offer of a lucrative lecture tour in the US).

At Coole, he was very much at home, taking photographs, playing with the grandchildren, going on long walks and drives, spending the evening talking and playing the piano. They were, Lady Gregory wrote, pleasant house guests: ‘The Shaws are here, they are very easy to entertain, he is so extraordinarily light in hand, a sort of kindly joyousness about him and they have their motor so are independent.’ On one occasion Shaw got lost on a long walk and had to be rescued by locals not arriving back until close to midnight. He also took photographs outside and inside the house.

She wrote to Yeats: ‘GBS is laid up with one of his bad headaches. He has been well up to now and cheery... Mrs. Shaw was lamenting about not having him painted by a good artist and I suggested having John over and she jumped at it and Robert is to bring him over on Monday.’ Augustus John who had been staying in Dublin would soon arrive and Shaw prepared himself for the session as Lady Gregory noted:

‘Augustus John wired from Dublin yesterday that he would come out today. GBS had his hair cut in Galway yesterday but too much was taken off while Hayes McCoy was telling him that a German warship had sailed into Galway Bay but when the admiral put up his spy glass and saw the ruins, he said “We must have been here already” and sailed away.’

John wasn't in the best of form when he arrived. He had spent the previous few days in Dublin with the surgeon poet Oliver St John Gogarty whose ‘magical exuberance and joie de vivre seemed to blossom best on the basis of “John Jameson” but this underpinning required regular renewal’. Having ‘floated his intellect’ with Gogarty, John arrived in Coole in poor shape (‘contrite and shattered’ according to Shaw) but, thanks to a trip to Gort with Shaw's chauffer to procure a curing concoction, he was soon fit to ride horses with Robert Gregory and get painting.

Lady Gregory asked him first to paint her grandchild Richard. John had avoided painting him in the past and was suspicious that this was the real reason for the invitation to Coole. He nevertheless painted both children (he had admired Anne Gregory as a subject) but produced what they considered ‘a very odd’ picture with ‘enormous sticky out ears and eyes that sloped up the corners rather like a picture of a china-man’.

Shaw was soon ready to be painted and John worked assiduously to

capture his likeness: ‘…he painted with large brushes

and used large quantities of paint’, he wrote to Mrs Patrick

Campbell, ‘over the course of eight days he painted six

magnificent portraits of me unfortunately he kept painting them on

top of one another until our protest became overwhelming, only

three portraits have survived’. Elsewhere, he wrote:

‘Like Penelope he gets up early and undoes the work of the

day before. But the sitter will strike presently: besides my

vanity rebels against being immortalised as an elderly caricature

of myself.’

John described the process: ‘Shaw’s head had two

aspects, as he pointed out himself, the concave and the convex. It

was the former I settled on at the start. I produced two studies

from that angle and a third from another. In the last he is

portrayed with his eyes shut as if deep thought. Although he had

consumed his midday vegetables, there was no question of nodding:

he had avoided a surfeit.’ Shaw called this later ‘the

blind portrait’:

‘It got turned into a subject picture entitled “Shaw Listening to Someone Else Talking” because I went to sleep while I was sitting and John , fascinated by the network of wrinkles made by my shut eyes, painted them before I woke and turned a most heroic portrait into a very splendidly painted sarcasm.’ Despite telling Yeats that John had portrayed him as an inebriated gamekeeper, Shaw purchased this and another favorite of the portraits, the one with - chiding John for charging too little. (The sleeping Shaw sometimes titled: ‘The Philosopher in Contemplation’ or ‘When Homer Nods' eventually made its way into the Queen’s Collection at Clarence House, London.)

While not painting John and Shaw went for a drive to Ballyvaughan to try out Shaw's new colour camera. There they took pictures of each other with it. ‘Results not bad’, according to John. Shaw also took the camera inside, as Lady Gregory wrote:

‘Thursday 29th GBS came in to photograph me ten minutes ago at my writing table, and I said it was one of life's ironies that I who had also done some much literary work should be photographed writing, as I was, to engage a kitchen maid! Just after I had begun this letter he took another and said we must offer a prize to whoever could guess by the expression whether I was writing to the kitchen maid or to you!’

From John too is an account of their evening in Coole:

‘In the evenings we sometimes collected in the drawing room. Shaw would, when so disposed seat himself at the piano and sing a succession of pieces in his gentle baritone. His effortless, unassuming and withal accomplished performance was welcomed by everybody. His conversation, however, (at any rate in my experience) was sometimes apt to be irritating. The style proper to privacy is not that suitable to the platform but this practiced orator seemed sometimes to over look the distinction. Mrs Shaw and Lady Gregory, each in her amiable way, adopted a humorous, appreciative but slightly aloof attitude, as if in the presence of a difficult, precocious but an essentially lovable wonder child.’

Read ‘Commonsense about the War' by George Bernard Shaw in full here

The war must have been the subject of many of those evening conversations. Shaw began to write at Coole what he intended to be his next great pamphlet, a sequel called: ‘More Commonsense about the War.’ In all likelihood, he used those evening sessions to rehearse some of his arguments. He wrote from Coole:

‘The war is going by its own horrible momentum because the imbeciles who could not prevent the Junkers from beginning it are equally unable to make them stop it; and there is nothing but mischief in it now that we have shown the Prussians that we can be just as formidable ruffians as they. I am working at Uncommon Sense About the War. Compared with it, my poor common sense will seem like a stale article from the morning post.’

Lady Gregory too was attuned to the war debate going on around her and records in her journal conversations she had and comments she overheard from local people about the war. A full chapter of her book, Seventy Years contains folklore on the war from her journals. For example, from 2 May 1915, she noted Johnny Quinn from Duras:

‘The Germans are showing some slacking, but they are strong enough yet. Sure they were educated to the army, not like Kitchener’s million men that if you would put a gun in their hand wouldn’t hit a haycock. A lad that went out from Gort and that came back was telling me if you put an egg on your head and let it fall it would frighten them. Devilment in the air and devilment on the earth and under the sea. It is the greatest war the world ever saw.’

Robert's presence during those days would have also focused attention on the recruitment question in Ireland. He had decided to enlist when the war began but had to delay to sort out the sale of part of the estate. Shaw had already been encouraged to enter into the debate in Ireland and had a major letter on the issue published in The Freeman's Journal the previous November. Lady Gregory's other major concern was the state of her theatre. Yeats was writing from London about further issues developing with the management of the company. So from these conversations came the genesis of a new dramatic work. Shaw promised her a play about the war, about recruitment, for the Abbey.

On 7 May Lady Gregory had a sense of foreboding, recalling a feeling she had when her sister Gertrude had died at childbirth. Her grandson had become upset and she linked this to a memory of parting with Robert when he was a child that ‘this roughness might be a foretaste of his school-life among strangers'. She was told that the mail boat had been torpedoed and recalled saying ‘that she was glad Hugh Lane was still in New York and remembered that Robert said nothing but turned away’. A cable confirming that Hugh Lane was on the Lusitania and was missing came soon after. Shaw asked what he could do to help and she replied ‘I said I longed to be alone, to cry, to moan, to scream if I wished. I wanted to be out of hearing and out of sight. Robert came and was terribly distressed; he had been so used to my composure’.

Sir Hugh Lane, then Director of the National Gallery of Ireland, was on board the famous Cunard Steamer the Lusitania when it was torpedoed by a German U-Boat off the coast of Kinsale, Co. Cork, in May 1915. (Image: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

Shaw and his wife returned by boat to England on 9 May. Many on board with them were survivors of the Lusitania. Lady Gregory too, left for London, still unsure of Hugh Lane's fate. His body was never found. Shaw drew further criticism in his response to the coverage of the Lusitania sinking. Asked by a press agency to comment on Pope Benedict XV 's statement of horror at the 'frightful crime' of the sinking he said, he believed it was not the business of the Pope to commend himself to the ethical ideas of the masses:

‘...and certainly the ‘ethical’ outlook that finds romantic excitement in the thousands of young soldiers at Neuve Chapelle and Aubers by the most infernally cruel methods and then bursts into screams of horror and vindictive fury because a ship full of civilians have been surprised by an easy death seems badly in need of the sternest Papal rebuke for its callous selfishness. The Pope can hardly be expected to represent God as sharing the general American and British belief that saloon passengers have more valuable souls than common soldiers because they have heavier bank balances.’

The strength of his views is reinforced by news then trickling out from Gallipoli as he put it later:

‘To me with mind full of the hideous cost of Neuve Chapelle, Ypres and the Gallipoli landing, the fuss about the Lusitania seemed almost a heartless impertinence, though I was well acquainted personally with the three best known victims and understood better than most people the misfortune of the death of Lane. I even found grim satisfaction; very intelligible to all soldiers, in the fact that the civilians who found the war such splendid British sport should get a sharp taste of what it was to be actual combatants. I expressed my impatience very freely, and found that my very straightforward and natural feeling in the matter was received as a monstrous and heartless paradox.’

Shaw saw his play Man and Superman have its London premiere to excellent reviews and good houses that summer. He had also contributed to the preparation of a document with Leonard Woolfe and the Fabian research group that proposed a ‘League of Nations’ to prevent war. This was published under the heading ‘An International Government’ in the New Statesman and later as a book (for which Shaw wrote an unused preface), and is credited as inspiring the post war League. He completed the piece to be called ‘More Commonsense about the War’ that updated his case against the war but Clifford Sharp and Beatrice Webb refused to publish it in the New Statesman.

Lady Gregory had stayed with the Shaws in London in June as the news of Lane's death was confirmed. She very quickly took on the role as guarantor of his legacy working to achieve his ambition of a modern art gallery in Dublin, trying to confirm his bequest of a selection of his valuable collection of paintings for this purpose and finding a suitable successor as Director of the National Gallery. As ever Yeats was her partner in this endeavor even arranging séances to contact Lane's spirit on her behalf so they could locate his will. Both were also working hard to keep the Abbey company going. (It was having serious business difficulties and they sacked the business manager A.P. Wilson that summer).

In the midst of this activity, Shaw confirmed to Lady Gregory that he was working on his promised play, in a telegram from Torquay on 2 September, and said that he would begin drafting it on the following day. He had in fact written the first piece of dialogue on 23 July while still in London. It had a title O'Flaherty V.C.:

‘- Can’t you explain to her what the war is about?

- Arra, and how the divil do I know what the war is about?

- You shouldn't have enlisted if your conscience didn't tell (you) it was a righteous war.

- I wouldn't have done it if I had been sober. What with the drink, and the offer of money, and me being not afraid of anything but my mother, I was over persuaded.

- But you know the Germans are in the wrong, don't you?

- Of course I do; and they're trying to shoot me and gas me and kill and destroy me from morning till night.’

On 14 September, Shaw wrote to Lady Gregory with an update: ‘O’Flaherty V.C. may now I think, be regarded as a certainty. I have finished the short-hand draft.’ He told her that it was one act, lasting about forty to forty-five minutes and with clear instructions on the casting (the V.C.: Arthur Sinclair, Sydney Morgan the retired General, an old woman - Sara Algood and a young parlor maid) and gave a brief synopsis:

‘The scene is quite simply before the porch of your house, supposed for the moment to be the country seat of Morgan. Small but important parts are played by a thrush and a draw. Properties: a garden seat and an iron chair (as at Coole), also a gold chain, looted by O'Flaherty for presentation to the parlor maid. O'Flaherty and the general are in khaki; and the two women are in correct local colour. A band capable of playing a few bars of God Save the King and a little more of Tipperary had to be heard ‘off’; and patriotic cheers will also be required, though the cheerers like the band will be invisible. I think that gives you everything you need. It is all quite cheap and simple and can be done anywhere and anyhow. Unfortunately, I cannot be so reassuring about the play itself. When it came to business, I had to give up all the farcical equivoque I described to you, and go ahead straightforwardly without any ingenuities or misunderstandings. The picture of the Irish character will make the Playboy seem a patriotic rhapsody by comparison. The ending is cynical to the last possible degree. The idea is that O'Flaherty's experience in the trenches has induced him a terrible realism and an unbearable candor. He sees Ireland as it is, his mother as she is, his sweetheart as she is; and he goes back to the dreaded trenches joyfully for the sake of peace and quietness. Sinclair must be prepared for brickbats.

I am sorry: c'était plus fort que moi. At worst, it will be a barricade for the theatre to die gloriously on.’

Lady Gregory replied from Coole on 9 September:‘such is my confidence in you that from the moment you had first spoken of O'Flaherty I had never a moment's doubt as to his coming punctually into being. I long to see him.’ She updated Shaw on the difficulties with the company and had some family news:

‘I am not very light-hearted, for Robert is carrying out his desire of this time last year, and is going to war. He couldn't go then because there was no one to look after the sale and transfer of the estate, but now that is done, and the desire comes uppermost again, and he is in London and wires that he will be home tomorrow, that all is settled, he has ten days leave. He has got a commission, but I don't know if he is going in for the Artillery or for Flying. He wanted one or the other. Whether he is right to go, I don't know. I daresay I should go if I were in his place, but I feel just now and since the Lusitania I should like to kill Germans and I don't think he is so ferocious. The only thing I (am) sure of is that he ought to make up his own mind about it, and so I would say nothing. But when I look at Margaret and the little things and think in what an unsettled state Ireland still is, my heart breaks.’

She told Shaw the latest news on the Lane paintings and the Gallery appointment and said of the Abbey that there was a plan that she and Yeats, who was staying with her at Coole, had agreed:

‘I don't think we should have had patience to go on as we are now, but that partly from my talk with you, my mind cleared itself: and I felt that if we can keep it alive till the end of the war and the beginning of Home Rule, we can give it over to the nation, buildings, company and stock in trade. We should give it into the hands of trustees, more or less Nationalist, anyhow those who are anxious to help the new government on, and let them do their best with it.’

She finished with an account of her recent writing, a play called Hanrahan's Oath and two lectures for her impending trip to America, one called ‘Laughter in Ireland’, in which Shaw features: ‘The satire of the old bards was still in the blood, the satire that used to raise blisters on the person satirized. I take Mr. Bernard Shaw as the the chief figure of that reaction. Mr. Yeats says of him that he has done more than any living man to shatter the complacency, to shake the nerves of the English.’

Shaw in reply says of Robert's decision: ‘Your news about Robert does not make me any more amiable about the war. They will have to capitulate all round when they are nine tenths ruined.’ On 26 September, he sent the first proof of O'Flaherty V.C. (with some scribbled corrections) to her in Coole.

The very title of the play was itself a challenge. The award of the Victoria Cross to then Lance-Corporal Michael O' Leary of the Irish Guards for conspicuous bravery on 1 February 1915 at Cuinchy, had been used as part of the recruitment campaign in Ireland and posters with O’Leary V.C. were displayed throughout the country.

.jpg)

Lance-Corporal (later Sergeant) Michael O'Leary was awarded the Victoria Cross in 1915 for single-handedly storming and capturing a German barricade at Cuinchy, France. (Image: © Imperial War Museum)

The play opens with the sound of a thrush and the distant sounds of God Save the King and A Long Way to Tipperary as the title character Private O'Flaherty V.C. and retired General Sir Pearce Madigan return from a recruiting meeting to the porch of Madigan House, both dressed in khaki. O'Flaherty's mother is in the house where his prospective girlfriend Tessie also works. Despite his efforts at recruitment, O'Flaherty makes no claims for valor:

‘O'Flaherty: Arra, sir, how the divil do I know what the war is about?

Sir Pearce: What O'Flaherty; do you know what you are saying? You sit there wearing the Victoria Cross for having killed God knows how many Germans and you tell me you don't know why you did it?

O'Flaherty: Asking your pardon Sir Pearce, I tell you no such thing. I know quite well why I kilt them. I kilt them because I was afeard that, if I didn't, they'd kill me.’

He says of the award of the V.C.:

‘Sure what's the Cross to me, barring the little pension it carries? Do you think I don't know that there are hundreds of men as brave as me that never had the luck to get anything for their bravery but a curse from the sergeant, and the blame for their faults of them that ought to be their betters? I've learnt more than you think, sir; for how would a gentleman like you know what a conceited creature I was when I went from here into the wide world as a soldier? What use is all the lying, and pretending and humbugging, and letting on, when the day comes to you that your comrade is killed in the trench beside you, and you don't as much look round at him until you trip over his poor body, and then all you say it to ask why the hell the stretcher-bearers don't take him out of the way. Why should I read the papers to be humbugged and lied to by them that had the cunning to stay at home and send me to fight for them? Don't talk to me or any soldier of the war being right. No war is right; and all the holy water that Father Quinlan ever blessed couldn't make one right.’

Nor does he have any time for the call to patriotic duty:

‘Sir Pearce: Does Patriotism mean nothing to you?

O'Flaherty: It means different to me than what it would to you, sir. It means England and England's King to you. To me and the like of me, it means talking about the English just the same way the English papers talk about the Boshes. And what good has it ever done here in Ireland? It's kept me ignorant because it filled my mother’s mind, and she taught it should fill my mind too. It's kept Ireland poor, because instead of trying to better ourselves we thought we were the fine fellows of patriots when we were speaking evil of Englishmen that were as poor as ourselves. The Boshes I kilt was more knowledgeable men than me: and what better am I now that I've kilt them? What better is anybody.’

O'Flaherty has told his mother that he is gone to fight with the French and the Russians, as she would believe they are assured to be against the English of whom she does not have a high opinion:

‘…she says Gladstone was an Irishman, sir. What call would he have to meddle with Ireland as he did if he wasn't?

Sir Pearce: What nonsense! Does she suppose Mr. Asquith is an Irishman?

O'Flaherty: She won’t give him any credit for Home Rule. She said Redmond made him do it.

She says you told her so... She says all the English Generals is Irish. She says all the English poets and great men were Irish. She says the English never knew how to read their own books until the Irish taught them. She says we're the lost tribes of the House of Israel and the chosen people of God. She says that the goddess Venus, that was born out of the foam of the sea, came up out of the water in Killiney Bay off Bray Head. She says that Moses built the seven churches and that Lazarus was buried in Glasnevin.Sir Pearce: Bosh! How does she know he was? Did you ever ask her?

O'Flaherty: I did sir

Sir Pearce: And what did she say?

O'Flaherty: She asked me how did I know he wasn't and fetched me a clout on the side of my head.

Sir Pearce: But have you never mentioned any famous Englishman to her and asked her what she had to say about him?

O’Flaherty: The only one I could think of was Shakespeare, sir; and she says he was born in Cork.’

The General's exasperation is tempered by O'Flaherty's wider observation: ‘she's pigheaded and obstinate: there's no doubt about it. She's like the English: they think there is no one like themselves. It's the same with the Germans, though they're educated and ought to know better. You'll never have a quiet world till you knock the patriotism out of the human race.’

In such a short work Shaw manages to weave in a number of his key pre-occupations: the attitude of the Church to war; the ambiguity in dealing with Belgian refugees; armchair Generals with old fashioned and detached views on duty and responsibility; the exaggerations of recruitment propaganda; the class conflicts between the landowners and their tenants; even Horace Plunkett's vain efforts to promote agricultural development. But at the climax of the play is the disillusionment that O'Flaherty sees when he realises that his mother and girlfriend are more interested in separation allowances and war pensions than any worry of the perils of war or the bigger issues being fought for:

'O'Flaherty: What's happened to everybody? That's what I want to know. What's happened to you that I thought all the world of and was a feared of? What's happened to Sir Pearce, that I thought was a great general and that I now see to be no more fit to command an army than an old hen? What happened to Tessie, that I was mad to marry a year ago, and that I wouldn't take now with all Ireland for her fount use? I tell you the world's creation is crumbling in ruins about me and then you come and ask what's happened to me?’

And following a‘tempest of wordy wrath’ with all four characters shouting at each other as a noisy ‘quartet fortissimo’, O’Flaherty gives his decision in the quiet aftermath:

‘What a discontented sort of animal a man is, sir! Only a month ago, I was in the quiet of the country out at the front, with not a sound except the birds and the bellow of a cow in the distance as it might be, and the shrapnel in the heavens, and the shells whistling, and maybe a yell or two when one of us was hit; and would you believe it, sir, I complained of the noise and wanted to have a peaceful hour at home. Well them two has taught me a lesson. This morning, sir, I was telling the boys here how I was longing to be back taking my part for King and country with the others, I was lying, as you well knew, sir. Now I can go and say it with a clear conscience. Some likes war's alarums and some likes home life. I've tried both, sir; and I'm all for war's alarums now. I always was a quiet lad by natural disposition.

Sir Pearce: Strictly between ourselves, O'Flaherty, and as one soldier to another (O'Flaherty salutes but without stiffening), do you think we should have got an army without conscription if domestic life had been as happy as people say it is?

O'Flaherty: Well, between you and me and the wall, Sir Pearce, I think the less we say about that until the wars over, the better. (He winks at the General. The General strikes a match. The thrush sings. A jay laughs. The conversation drops.)’

By the time the full copies of the play were sent to Lady Gregory she was on her way to America and in the meantime it was left to Yeats to follow up with the arrangements for the production of the play. Yeats had spent most of the summer at Coole, he was working on the latest draft of his play, The Player Queen. In August he sent off his poem, written earlier that year ‘On being asked for a War Poem’ to Edith Wharton. It succinctly stated his position.

‘I think it better that in times like these

A poet's mouth be silent, for in truth

We have no gift to set a statesman right

He has had enough of meddling who can please

A young girl in the indolence of her youth,

Or an old man upon a winter's night.’

('On being asked for a War Poem', W.B. Yeats, 1915.)

He sent a copy of the poem to Henry James who was a friend of Edith Wharton. (She had asked for a poem for a war anthology she was preparing.) He added to James: ‘it is the only thing I have written of the war or will write so I hope it may not seem unfitting. I shall keep the neighborhood of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus hoping to catch their comfortable snore till bloody frivolity is over.’

During this time he was engaged in attempting to secure funding for James Joyce from the British authorities, having being asked to help by Ezra Pound. The pension from the Royal Literary Fund was arranged through the auspices of Edmund Gosse to whom Yeats wrote a number of letters from Coole in the summer of 1915 in what was ultimately a successful application. Gosse required assurances not only of Joyce's talent but also of his politics not wanting to support someone who might be subversive on the war issue. Yeats dealt with the issue deftly:

‘My Dear Gosse: I thank you for what you have done; but it has never occurred to me that it was necessary to express sympathy “frank” or otherwise with the “cause of the allies”. I should have thought myself wasting the time of the committee. I certainly wish them victory, & as I have never known Joyce to agree with his neighbors I feel that his residence in Austria has probably made his sympathy as frank as you could wish. I never asked him about it in any of the few notes I have sent him. He had never anything to do with Irish politics, extreme or otherwise, and I think disliked politics. He always seemed to me to have only literary & philosophic sympathies. To such men the Irish atmosphere brings isolation not anti-English feeling. He is probably trying at this moment to become absorbed in some piece of work till the evil hour has passed. I again thank you for what you have done for this man of genius.’

Yeats was of course correct, Ulysses was then well underway and would be completed for publication in 1922. Joyce got his first installment of the grant at the end of August and wrote to Yeats, thanking him for helping in these 'calamitous times'. He had also sent a copy of his play Exiles hoping the Abbey might produce it. (Joyce to Yeats, 1 September 1915, Letters V. 2)

Having returned to London in October, Yeats witnessed a Zeppelin raid close to the house where he was staying. Whether as a result or by coincidence he wrote a poem, the ‘first since Coole’ he told Lady Gregory and which begins a sequence of three where a figure like Maud Gonne is addressed. The danger of war is not far away:

‘Others because you did not keep

That deep-sworn vow have been friends of mine;

Yet always when I look death in the face,

When I clamber to the heights of sleep,

Or when I grow excited with wine,

Suddenly I meet your face.’

('A Deep-sworn Vow', W. B. Yeats, 17 October 1915)

However, his main pre-occupation was the future of the Abbey Theatre company and here there was a major change with John Ervine replacing A.P. Wilson as manager. In the press announcement of the appointment it was stated that he would produce among other plays ‘a new piece in one act entitled Michael O'Flaherty V.C.’ The play was set to open on 23 November.

There was initial difficulty with the casting as Arthur Sinclair had left the company but following an intervention by Shaw with Yeats he was hired as a one-off to play the part that had been written for him. A more serious obstacle arose as Yeats reported to Lady Gregory, the British authorities had a problem with the play:

‘I had a wire from (W.F. Bailey) saying that the Bill for 23rd November will have to be changed. That Bill was Shaw's play. I went off to Shaw and found him in the middle of lunch. I pointed out that the telegrams must mean that the authorities objected to his play. He wired to Bailey who replied that it was the military. Shaw then wrote a detailed letter to (Sir Matthew) Nathan putting the case before him. I should say that my very first sentence had been that it was out of the question our fighting the issue. Shaw, I thought, was disappointed. He said, if Lady Gregory was in London she would fight it, but added afterwards that he didn't really want us to but thought you would do it out of love of mischief. I told him that was a misunderstanding of your character.’

Nathan was the Under Secretary for Ireland and Lady Gregory and Shaw had joined in resisting the attempt by the English censor and Dublin Castle to ban the Shaw play The Shewing-up of Blanco Posnet in 1909. W.F. Bailey was a friend of Lady Gregory, an advisor to the Abbey in Dublin and had been at Coole at the same time as the Shaws that summer. Shaw summed up his defense in a letter to Yeats that evening:

‘The line I took was that the suppression of the play will make a most mischievous scandal, because it will at once be assumed that the play is anti-English; that will be exploited by the Germans and go around the globe; that their will be no performance to refute it; and that a lot of people who regard me as infallible will be prevented from recruiting, shaken in their patriotism etc. etc.’

On 14 November, Yeats forwarded to Shaw the letter from Bailey in Dublin which explained what he believed the worries were. Bailey was to meet Nathan about it later that evening:

‘I sent it to the military authorities and they are reading it. I think the view is that with an “educated” audience it would be alright but the danger is that it may be misinterpreted and the house be made an audience of warring factions which of course would be bad for the theatre.’ Bailey points to the title as a problem: ‘The danger is that people will consider it rather an insult to Lieutenant Michael O'Leary V.C. and if he sees it I imagine that he would be very angry and take very strong steps indeed.’

He pointed to the fact that posters of O'Leary V.C. are placarded across the city and concluded:

‘Shaw says that it could be made a good recruiting play I hear. Well that may be but it is hardly one at present. Having regard to the manner in which it impartially hits all sides I would not be afraid of it but for the feeling that it may be regarded as an insult to O'Leary - “the Irish Hero”. Such a play would be all right at any time but the present when the whole question of recruiting is at a very critical stage.’

Shaw wrote next to Yeats proposing that the play be put on for the military staff to overcome their objections:

'If the play makes them laugh, they will pass it cheerfully without the smallest regard to its meaning and without the smallest regard to its meaning or tendency. If not they will stop it, and would even if it were crammed with loyal sentiment and contained a dozen Remember Belgium’s on every page. In which they would be perfectly right. It is written so as to appeal very strongly to that love of adventure and desire to see the wider world and escape from the cramping parochialism of Irish life which is more helpful to recruiting than all the silly placards about Belgium and the like, which are the laughing stock of Sinn Fein...’

On the same day Sir Horace Plunkett wrote to Shaw from Dublin urging a postponement:

‘If the play were postponed a while it seems to me, with very small amendments, it might be safely produced and what to me is its moral is so good that it would be a pity that it should be lost in minor issues. The change wrought in O'Flaherty by his outlook to the world beyond his parish is to my mind a valuable contribution to Irish progress. It seems rather a pity to teach the lesson when the attention of the important pupils is elsewhere. When this conscription question ceases all could laugh and learn.’

Sir Matthew gave his verdict on 16 November in a letter to Shaw from Dublin Castle; he had consulted the Lord Lieutenant, Lord Wimborne, the military commander General Friend as well as discussing it with Bailey and Plunkett and reading the play:

‘I find they are definitely of the opinion that the representation of this play at the present moment would result in demonstrations which could do no good either to the Abbey Theatre or to the cause that at any rate a large section of Irishmen has made their own. By such demonstrations the fine lesson of the play would be smothered while individual passages would be given a prominence you did not intend for them, with the result that they would wound susceptibilities naturally more tender at this time than at others and be quoted apart from their context to aid propaganda which many of us believe are inflicting injury on Ireland as well as on my country. In these circumstances I think and so does General Friend that the production of this play should be postponed till a time when it will be recording some of the honour and pathos of the past rather than of a present national crisis.’

He did agree with the view of the play ‘that this war does give to the most thinking of all peasantries the chance of contact with the wider world which will enable them to rise above the hopelessness derived from their old recollections and surroundings’.

Shaw and the Abbey agreed to withdraw the play and when news of this was announced both Shaw and the Abbey manager Irvine gave interviews to the press to say that it had not been banned merely postponed. Shaw worried about inaccurate reports that the play was suppressed asked a Guardian journalist:

‘I therefore appeal to the press, if they must circulate an unfounded report, at all events to make sure that the author has no more desire to discourage recruiting in Ireland than the military authorities themselves. Neither I nor the Abbey theatre would think for a moment of producing a play if the military authorities felt it could do the slightest harm to recruiting or anything else.’

Shaw went on in another interview in the Irish Independent on 17 November to counter any inference that the play was referring to O'Leary V.C.:

‘…the gratuitous identification of O'Flaherty with O'Leary is extremely annoying to me, and may possibly be offensive to Lieut. O'Leary. I can only take this opportunity of offering him my apologies, protesting that I am entirely innocent in the matter.’

In further correspondence, Nathan held out the possibility of the play being performed at a later date and met Shaw in London in December to discuss it. He also briefed him on the developing concerns with Sinn Féin in Ireland as his note of the meeting outlined:

‘I suggested the possibility of some counteracting literature to the stuff they circulate and the necessity for it to be on rather a high plain. He asked me to send him copies of leaflets issued by the Sinn Féiners and also by the Recruiting Department and he would see what he could do.’

Shaw, on receiving the copies, sent Nathan a draft poster in response at the end of December.

Yeats assured Lady Gregory there had been no lasting damage:

‘I think Shaw's faint idea that we should fight the thing disappeared at once. In all his letters he has been emphatic about putting ourselves without reserve at the disposal of the authorities. As it is generally known in Dublin that we have done so, I do not think the theatre has suffered.’

In the same letter he expresses his anxiety about an outstanding proposal to have the Viceroy present at an Abbey performance:

‘When I suggested this a year ago, the Home Rule bill had just become law and Redmond had just made his speech. There was a new fact that everyone recognised. I am afraid it is too late unless we can get another new fact. What I am afraid of is that our Pit in which all the ancient suspicions are alive again will either desert the theatre or boo the Viceroy. I do not know which will be worse for us.’

But away from home, in America, Lady Gregory's fears were more personal, that of a mother for a son: ‘It is a bad summer to look back on, too many shocks - first Hugh. Sir F. Donaldson says fourteen are killed out of every thirty aviators who go out. If I get through America well I shall have new courage, and I hope I may make enough money anyhow to put off cutting trees.’

Read the full text of George Bernard Shaw's O'Flaherty V.C.: A Recruting Pamphlet here

Postscript

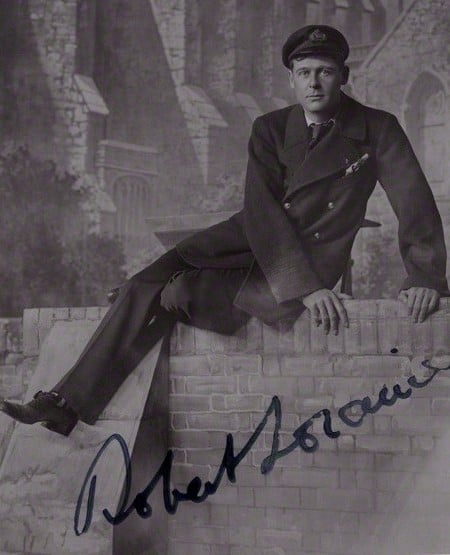

O'Flaherty V.C. was to receive its first production at Treizennes in Belgium in February 1917 when Shaw visited the front on the invitation of the commander of the British forces Douglas Haig whom he met on the visit, which had included the aftermath of the Somme. (Shaw said of Haig: ‘He made me feel that the war would last thirty years and he would carry it on irreproachably until he was superannuated.’) O'Flaherty was played by Shaw's friend, the actor now airman, Robert Loraine, for whom the Shaws had agreed to act as next of kin when he enlisted. The other parts were played by officers Royal Flying Corps with Lady Gregory's son Robert as Tessie. Loraine had been a fighter pilot but having been wounded was now desk-bound writing to the relatives of downed airmen and trying to keep spirits up by organising plays and entertainments. Shaw was observed laughing throughout the play. When asked by an officer why he was enjoying his own jokes he replied: ‘Do you know, if I had thought the stuff would prove to be so poor as this, I'd never have written it.’ He was to read the play later that year to a hospital full of wounded soldiers near his home in Ayot. He told Lady Gregory: ‘They gave me three cheers and laughed a good deal but the best bits were when they sat very tight and said nothing.’

Actor, and friend of George Bernard Shaw, Robert Loraine as Jam Redlander in The Man From the Sea in 1910. (Image: © National Portrait Gallery, London)

The play did get a proper professional premiere in 1920 in New York and, before Shaw, in London where Arthur Sinclair played O'Flaherty but it was not until 1927 that Lady Gregory saw it for the first time. She was in Dublin that November, staying with Molly Childers, whose husband Erskine had been executed during the Civil War and whose house had been raided in the aftermath of the murder of Kevin O'Higgins, as the police were looking for her son Bobby. It was still a dark time in Dublin and during her visit Lady Gregory met Éamon de Valera in a meeting arranged by Molly, to press the case for the Lane gallery: ‘He did not remember Lord Mayor O'Neill's hurried introduction, but knew my face. He looked older and darker and depressed but was interested about the Gallery but said there is little money to be had, and so much wanted for relief of unemployment... I said I was glad his party had come into the Dáil and he said, “But we have left a large section - some of them our best people - outside. Sinn Féin will not come in.” - This seems to pain him. He looked worn and sad. I said he had often been in our prayers in the old troubles.’

She had visited the Yeats children and gone to the Abbey the day before:

‘I had tea with Michael and Anne and told stories and played and romped with them till bedtime. And then, later to the Abbey to see O'Flaherty V.C. I had never seen it acted. It was very well done (Jack Dwan's Co.). Theatre crowded. I paid for my seat 3/9, the first time I had ever paid at an Abbey performance. (I as Patentee being responsible to see that there are no wild beasts on stage, and no men or women hung from the flies'!) But I was glad to see so big an audience of unfashionable people for O'Flaherty ...’

The subtitle of the play was now A Reminiscence of 1915 and for Lady Gregory the title with V.C attached to it must have had an added poignancy. Robert had become a major in the Royal Air Force and been awarded a military cross. Colonel Robert Loraine was his commander. She wrote to Robert Gregory on 23 January 1918, full of hope for the New Year. She had had an optimistic meeting about the Lane paintings, new trees were planted, there was political excitement with the potential breakdown of the (Irish) Convention (chaired by Horace Plunkett and to which Shaw had tried and failed to be nominated):

‘The Government are evidently going to try and make some settlement and one's hopes come up again that at last there may be political peace and that responsibility may bring conscience into the county.’ She had seen the grandchildren and sent him their wishes: ‘Oh what a happy world it might be with you back and the war at an end. God bless you my child.’

Two days later a message arrived as Lady Gregory wrote:

‘I was sitting at my writing table when I heard Marian come in very slowly. I looked up and saw she was crying. She had a telegram in her hand and she gave it to me. It was addressed to Mrs Gregory, and I thought “This is telling of Robert’s death, it is to Margaret they would send it”. The first words I saw were killed in action and then at the top, “Deeply regret”. It was on the 23rd that he had died. I said how can I tell her? Who will tell her? For Margaret was with the children in Galway.’

Robert Loraine wrote to her his letter of sympathy from the battlefield. Among other letters of sympathy were ones from Augustus John and George Bernard Shaw. Shaw wrote:

‘These things made me swear once; now I have come to taking them quietly. When I met Robert at the flying station on the west front, in abominably cold weather, with frostbite on his face hardly healed, he told me that the six months he had been there had been the happiest of his life. An amazing thing to say considering his exceptionally fortunate and happy circumstances at home, but he evidently meant it. To a man of his power of standing up to danger - which must mean enjoying it - war must have intensified his life as nothing else could; he got a grip of it that he could not through art or love. I suppose that is what makes the soldier.’

Lady Gregory thanked him for his letter: ‘I knew it would be helpful. Just that - danger and authority and the sense of power to do more that he had ever done- intensified his life - were the highlight in the picture.’ She asked of Yeats, reluctant to write of war, a fitting memorial in poetry, a poem that would be his monument. In all Yeats wrote four poems on this theme, some almost negotiations with Lady Gregory by his side. She was unhappy with the first 'Shepard and Goatheard' and the final one called 'Reprisals'. She was so unhappy with the latter that it was not published until after both their deaths. Yeats wrote it in 1920, in the midst of other tragedies, and took his inspiration from Shaw's letter as Lady Gregory recognised (‘he quoted words which GBS told him and did not mean to repeat -and which will give pain - I hardly know why it gives me so extra-ordinary pain...I fear the night.’)

Yeats had written:

Considering that before you died

You had brought down some nineteen planes,

I think you were satisfied,

And life at last seemed worth the pains.

'I have had more happiness in one year

Than in all the other years,' you said;

And battle joy may be so dear

A memory even to the dead

It chases common thought away.

Yet rise from your Italian tomb,

Flit to Kiltartan Cross and stay

Till certain second thought have come

Upon the cause you served, that we

Imagined such a fine affair:

Half drunk or whole-mad soldiery

Are murdering your tenants there;

Men that revere your father yet

Are shot at on the open plain;

Where can new-married women sit

To suckle children now? Armed men

May murder them in passing by

Nor parliament nor law take heed; -

Then stop your ears with dust and lie

Among the other cheated dead.

(23 November 1920)

Yeats had originally entitled this: 'To Robert Gregory, Airman', but even in its posthumous publication this was too raw a dedication. The more acceptable memorials were the two other poems: 'In Memory of Major Robert Gregory' and 'An Irish Airman Foresees His Death'. As Colm Tóibín has observed the pathos of the memorial comes 'not for the qualities claimed for Robert Gregory but from withholding his name from the body of the poem and in the second by turning him into an Irish Airman and handing him back to Coole’ which the war could not touch, the house his mother had guarded for him:

My country is Kiltartan Cross

My countrymen Kiltrartan's poor

No likely end could bring them loss

Or leave them happier than before.

Nor law nor duty bade me fight

Nor public men, nor cheering crowds

A lonely impulse of delight

Drove to this tumult in the clouds;

I balance all, brought all to mind,

The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind

In balance with this life, this death.(W.B. Yeats, 'An Irish Airman Foresees his Death')

This withholding of the name 'as if the poem can't bring itself to mention it', reflected as Tóibín observed, Lady Gregory’s own grief, where she in her journals refrains from using his name, referring to 'the grave in Italy' or the grave in Padua or ‘my darling’.

It is especially poignant, to reflect that, one day in these times, she sat at the ‘beautiful desk’ that had once been her husband's, as she had when Shaw photographed her years before, and, in her own hand, completed, with finality, the entry in the 1658 family bible:

‘William Robert Gregory, born May 20,1881, at 3 St. George's Place, London. He died in action, Jan.23, 1918, on the Italian Front, near Padua, in command of a Squadron; a Major in the Connaught Rangers, MC and Legion of Honour.’

Ed Mulhall is a former Managing Director of RTÉ News

& Current Affairs and Editorial Advisor to Century

Ireland

Further Reading

Lady Gregory, Coole, Dublin, 1971

Lady Gregory, Seventy Years, edited by Colin Smyth,

London, 1974

Lady Gregory, Selected Writings, London, 1995.

Dan H. Laurence and Nicholas Grene, Shaw,

Lady Gregory and the Abbey, Gerrard Cross 1993.

George Bernard Shaw, Collected Plays Volume IV, London

1972.

George Bernard Shaw, Collected Letters, 1911-1925, edited

by Dan H Laurence, London,1985

Stanley Weintraud,

Bernard Shaw 1914-1918 Journey to Heartbreak, London,

1973.

Colm Tóibín, Lady Gregory's Toothbrush,

Dublin, 2002.

Allen Dent editor,

Bernard Shaw and Mrs. Patrick Campbell Their Correspondence, London, 1952.

Roy Foster, W. B. Yeats, A Life, Volume 2, The Arch Poet,

Oxford 2003.

Michael Holroyd,

Bernard Shaw Volume 2, The Pursuit of Power, London

1989.

Michael Holroyd,

Bernard Shaw, The One Volume Definite Edition, London,1998.

A.M Gibbs, Shaw, Interviews and Recollections, London

1990.

W.B. Yeats, Collected Poems, London, 1950.

W.B. Yeats,

The Collected Works, of W.B. Yeats Vol. 1: The Poems

revised, edited by Richard J. Fiinneran, London, 1989.

Michael Holroyd, Augustus John, New York, 1976.

Augustus John, Autobiography, London,1975.

Mary Lou Kohfeldt,

Lady Gregory- the Woman behind the Irish Renaissance,London,1985

Judith Hill, Lady Gregory, An Irish Life, Cork,2011.

Richard Ellman, James Joyce, Oxford, 1983.

James Joyce Letters, Volume 2, edited by Richard Elman,

New York, 1966.

John S Kelly, A W.B. Yeats Chronology, New York, 2003.

Roger Norburn, A James Joyce Chronology, New York,

2004.

A M Gibbs, A Bernard Shaw Chronology, New York, 2001

Anne Saddlemyer and Colin Smythe eds,

Lady Gregory Fifty Years After, New Jersey, 1987.

The Collected Letters of W. B. Yeats. Electronic Edition,

Charlottesville, Virginia, USA, 2002

The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W.B. Yeats, edited

by Peter Alt and Russle K Alspach,New York,1966,

Michael Holroyd ed, The Genius of Shaw, London, 1979