Thomas Kent & Cork’s Rising Experience

By Mark Duncan

In the telling of the Easter 1916 story, Cork appears only on the margins. The reasons for this are not too hard to comprehend.

Here was a county that had thought about mounting insurrection, then thought better of it. This failure to mobilise left an unpleasant aftertaste, becoming, for some at least, a source of abiding regret that bordered on embarrassment. It left behind it, Liam de Róiste, the Gaelic scholar and then leading local Irish Volunteer, wistfully recalled, a trail of ‘heart burning, disappointments, and some bitter feelings. The hour had come and we, in Cork, had done nothing'. In the circumstances, the decision to remain inactive – encouraged by the intervention by local bishop Daniel Colohan and Cork City Lord Mayor W. T. Butterfield – was an understandable one, wise even in view of the failed landing of German arms on board the Aud and the confusion created by the countermanding order of Eoin MacNeill which delayed for a day, and altered completely, the character of the Rising that eventually took place.

In any case, with Dublin planned as the operational focus of the Rising, Cork was hardly alone in remaining remote from the fray. Yes, trouble flared in Galway, in Enniscorthy, Co. Wexford and in Ashbourne, Co. Meath, but so few were these locations and so limited was the fighting that it served only to underline the failure of the insurgents to ignite a wider rebellion across provincial Ireland.

For much of the country, the Rising of 1916 was experienced only in the heavy-handed and occasionally brutal backlash to it. Over 3,000 people were arrested across the island in its aftermath, but in Cork, for one family at least, the repercussions of the Rising were far more serious.

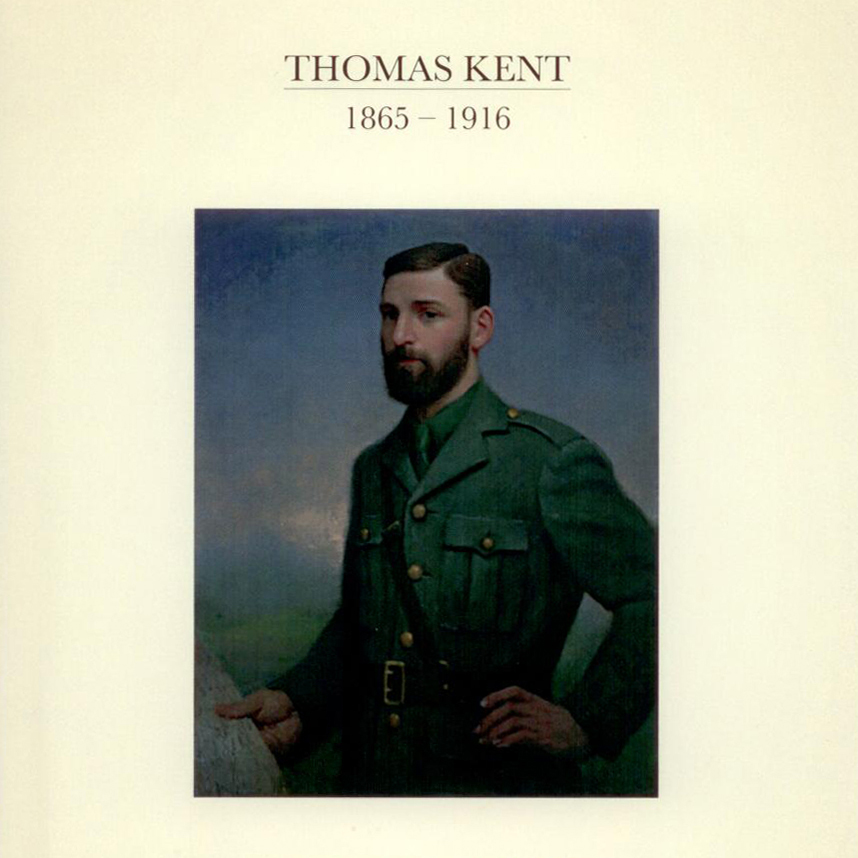

Thomas Kent and his brother William being arrested in Fermoy, Co. Cork.

For the Kents, a north Cork family farming on 200 acres, the Rising would end in a ‘blood sacrifice’ not of their own making. Rather, as the historian Peter Harte has put it, it was ‘the result of tragedy, not calculation’. In the early hours of the morning of 2 May 1916, a party of seven Royal Irish Constabulary officers from nearby Fermoy approached the Kent family home at Bawnard House in Castlelyons, then occupied by four unmarried brothers – David, Thomas, William and Richard Kent – and their octogenarian and long-time widowed mother, Mary. There are varying accounts of what transpired thereafter, but what is known for certain is that there was an exchange of gunfire which resulted directly in the death of two men: one of them was Head Constable William Rowe, a Wexford-born father of five, who was killed instantly, ‘the top of his head blown off’ by bullets coming from the Kent home; the other was Richard Kent, the youngest of the four brothers inside the house, who was shot when trying to escape following the arrival of military support and the surrender of his family – he died later from his wounds. There were other casualties, too. David Kent sustained injuries that necessitated treatment in Fermoy military hospital and he, alongside Thomas, were subsequently court-martialled and sentenced to death. The fourth brother William was tried and acquitted and, in the end, David’s sentence was commuted to five years penal servitude of which he would serve only one – he was released from his English prison as part of a general amnesty in June 1917. For Thomas Kent, however, there was no reprieve. On 9 May 1916, his hands firmly gripped around a set of rosary beads, this devout Catholic and tee-totaller, was executed by firing squad and his body buried in a shallow grave in the exercise yard of Cork Military Detention Barracks, later to become Cork Prison. Roger Casement apart, his was the only one of the 1916 executions to take place outside Dublin.

The decision of the authorities to target the Kents in May 1916 is not hard to fathom. In matters of political agitation, the brothers had what might be colloquially called form: they had been prominent in the land campaigns of the 1880s, serving prison time for their activities; they were involved in the cultural nationalist movement and were prominent in the local branch of the Gaelic League, as well as the GAA. And when Irish politics took a radical turn with the foundation of the Irish Volunteers in November 1913 – a response to the foundation of the Ulster Volunteer Force earlier that year – the Kent name was to be found associated with emergence of a local company of Volunteers.

The Kents opposed John Redmond's call to support the British war effort and remained active in a shrunken Irish Volunteer movement which they worked to reorganise and grow in the north Cork region. Inevitably, their efforts brought them again to police attention and on 13 January 1916 Thomas Kent was arrested in Fermoy under the terms of the Defence of the Realm Act for being in ‘possession of firearms and ammunition in the vicinity of the railway station, and conduct likely to prejudice recruiting and cause disaffection’. It was alleged that Kent, who was found carrying a parody of The Croppy Boy ridiculing John Redmond, had addressed a meeting at Ballynoe on 2 January in which he declared that ‘if the Germans landed in Ireland, taking it by force of arms, they would have just as much right to it as England’. Kent, who was speaking by way of introducing the leading local Irish Volunteer organiser Thomas McSwiney, further advised his audience to ‘fight for Ireland and be buried in consecrated ground, not dying like those in France, to be thrown into a bode’. Held for five weeks without trial, the case against Kent was later dismissed but not before the Cork Examiner denounced it as ‘ridiculous’. ‘If the Government wanted to take up all the ammunition and rifles in the hands of the Volunteers why did they not do so and take them from the City of Cork Training Corps at the Mardyke, the Irish National Volunteers at the Corn Exchange. They would have to get a special act of Parliament to do so, and they were working these things for political reasons...until the law was amended every man was entitled to have arms and munitions in his possession.’

The detention of Thomas Kent in the early months of 1916 raised issues of ‘due process’ that re-surfaced in the aftermath of his court-martial and execution in May of that same year. Kent was one of 15 men executed between 3 and 12 May, yet the trials of none were open to the press or public. This secrecy bred suspicion which in turn gave rise to questions in the House of Commons. On 11 May 1916, two days after Kent’s death by firing squad, Prime Minister Herbert Asquith informed the House of Commons that he had been ‘executed – most properly executed as everybody will admit – for murder’. But not everybody thought it proper. Four days later in the same chamber, William O’Brien addressed the Chief Secretary of Ireland and told him that Thomas Kent’s family were ‘respectable people’ and would suffer more from ‘the accusation of murder against him even than from his execution’. What’s more, he pressed for the publication of the evidence given at Kent’s court martial. O’Brien repeated the call to publish the evidence against Kent on 18 May as did Irish nationalist MP Laurence Ginnell on 4 July. In responding to Ginnell, Herbert Asquith offered a different explanation for Kent’s execution to that which he had previously provided. Where, on 11 May, he declared the crime committed by Kent to be that of ‘murder’, by early July it had changed to that of ‘taking part in an armed rebellion’. This was, of course, a travesty of the truth as whatever about Thomas Kent’s political convictions or his behaviour on the night of the RIC came knocking on the door of his family home (and the nobody could identify the person who had actually fired the shot that killed Head Constable Rowe), he had most certainly not partaken in the Easter Rising; rather he, like thousands of others, had become swept up in the repressive wave to which it gave rise.

Watch in full RTÉ Television's special programme on the State Funeral of Thomas Kent which took place in his home village in Cork on Friday, 18 September 2015.

The Aftermath of the Rising and the Commemoration of Thomas

Kent

The events of the 2 May 1916 at Bawnard House devastated the Kent

family. On 5 January 1917, a mere matter of months after two of

her sons had been killed and with a third languishing in a British

prison, Mrs Mary Kent, widowed since 1876, died at the family

home. Her passing – and her sacrifice – was widely

noted. For instance, in paying tribute to that ‘Spartan

Irish mother’, the members of the Cork Poor Law Union

unanimously passed a motion lamenting her loss and acknowledging

the contribution of her sons who had done ‘their duty to

Ireland according to their lights, and gave their lives for their

country’. For the two surviving brothers, the focus of their

service to Ireland now shifted to electoral politics, with William

becoming Sinn Féin’s first Chair of Cork County

Council in 1917 and David, released from prison in June 1917,

being elected unopposed as MP for Cork East as part of Sinn

Féin’s sweeping electoral success in 1918.

As for Thomas, his memorialisation was almost instant. By 1917, local newspaper reports appeared carrying references to a Thomas Kents Camogie club and shortly after, in 1918, they refer to the Fermoy Sinn Féin club as being named in his honour. Much later, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, the train station in Cork was renamed Kent Station and it was here, in May 2000, that Thomas Kent’s niece, Kathleen, unveiled a memorial plaque that had been commissioned and erected by a committee of railway workers. For the most part, however, the commemoration of Thomas Kent across the decades has been a private, dignified family affair, his descendants entering the grounds of what became Cork Prison to quietly remember his life and death. However, the exact resting place of Thomas Kent remained unknown until June 2015 when in the course of the reconstruction of Cork Prison the National Monuments Service of the Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht discovered and exhumed human remains close to the small monument that that had been erected in Kent’s honour. When DNA testing confirmed the remains to be those of Thomas Kent Taoiseach Enda Kenny offered the family a State Funeral which was accepted.

The resurrection of the remains of Thomas Kent was not without precedent. In 1965, the remains of Roger Casement had been exhumed from Pentonville Prison, where he had been hanged in August 1916, and returned for re-interment in Glasnevin Cemetery following a State Funeral during which full military honours were awarded and 30,000 thronged the streets.

A similar event occurred in October 2001 when a State Funeral was held for Kevin Barry and nine other IRA Volunteers of the War of Independence who were executed in Mountjoy Gaol between 1920 and 1921. The decision to add Thomas Kent to the list of re-interred martyrs of the revolutionary era did not pass without criticism. In June 2015, in a letter to The Irish Times, John A. Murphy, Emeritus Professor of History at UCC, described the archaeological 'dig' to locate Kent’s remains as not merely an ‘ill-conceived and undignified project’, but yet ‘another morbid, self-indulgent nationalist propensity’.

Whatever about Murphy’s wider objections, the re-burial and funeral ceremony afforded to Kent was certainly not lacking in dignity. More than 5,000 people filed passed his coffin as it lay in state at Collins Barracks, Cork, before it was removed to the village of Castlelyons where in front of family, dignitaries and hundreds of local onlookers, the remains of Thomas Kent were laid to rest in his family plot. It was, the Bishop of Cloyne William Crean observed in his funeral homily, ‘the final chapter in a long ordeal for the Kent family’.