Suppressing the Rebellion: The British Forces in 1916

In many accounts of the Rising those forces opposing the rebels are simply referred to as ‘the British’. There has, until recent years, been little interest in who the British actually were, and no real understanding of the men who served in Ireland. Essentially the British forces comprised two distinct groups. First were those regiments that were stationed in Ireland and responded to the Rising in the initial days, and second, troops that were brought into Ireland from Britain from the morning of Wednesday 26 April. By the end of the Rising there were approximately 16,000 British troops in Dublin. The British casualties during the week were 17 officers and 86 other ranks killed. In addition 46 officers and 311 other ranks were wounded.

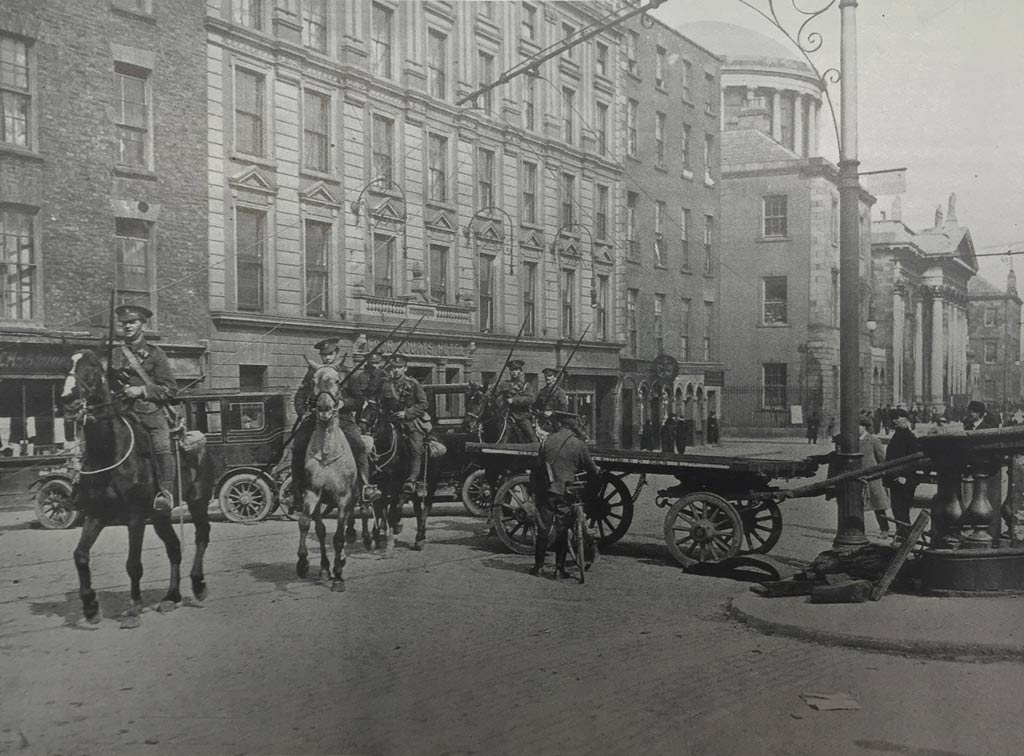

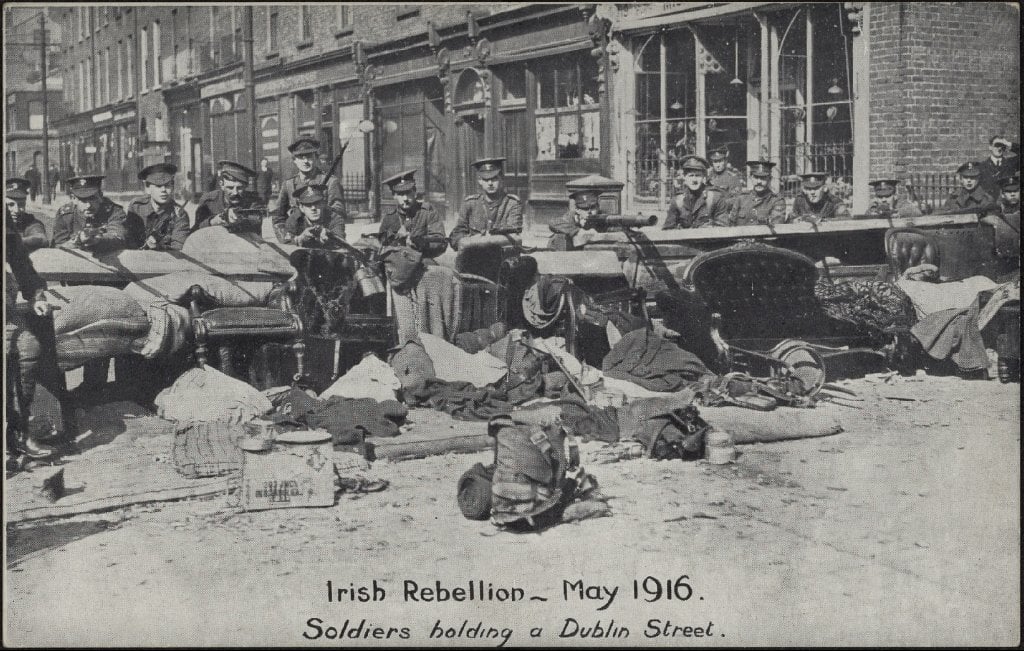

British cavalry troops near the Four Courts in the days after Easter Week. (Image: Dublin Rebellion and Aftermath, Manchester Guardian History of War 1916. Full collection availible at the National Library of Ireland)

Irish based forces

After the Rising began on Easter Monday the British authorities

had to move troops into the city as quickly as possible. What was

available militarily were largely reserve forces as the bulk of

the army was involved directly in the fighting in World War One.

The first troops to be activated were those stationed in Dublin.

At the Royal Barracks was the 10th Service Battalion of the Royal

Dublin Fusiliers. In Richmond Barracks was the 3rd Reserve

Battalion of the Royal Irish Regiment. The Marlborough Barracks

housed the 6th Reserve Cavalry, while at the Portobello Barracks

were the 3rd Reserve Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles. These

troops were moved during the afternoon of Easter Monday to various

parts of the city, and all came into contact with rebel positions

at various times. The Reserve Cavalry, for example, was shot at

from the GPO as its members trotted down O’Connell Street

and four men were killed.

During the late afternoon and evening of Easter Monday troops were moved from the largest military base in Ireland, the Curragh Camp, into Dublin by way of Kingsbridge station. Trains arrived every 20 minutes throughout the evening and moved into the city men from the 3rd, 8th and 9th Cavalry Brigades, the 5th Leinster Regiment, the 5th Royal Dublin Fusiliers, and the 25th Infantry Brigade. By Tuesday 25 April the troops that had moved into the city from the Curragh were joined by forces from elsewhere across the island. From Athlone came the 5th Reserve Artillery with four operational artillery pieces, from Belfast 1,000 men of the 15th Reserve Infantry Brigade and from Templemore the 4th Extra Reserve Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

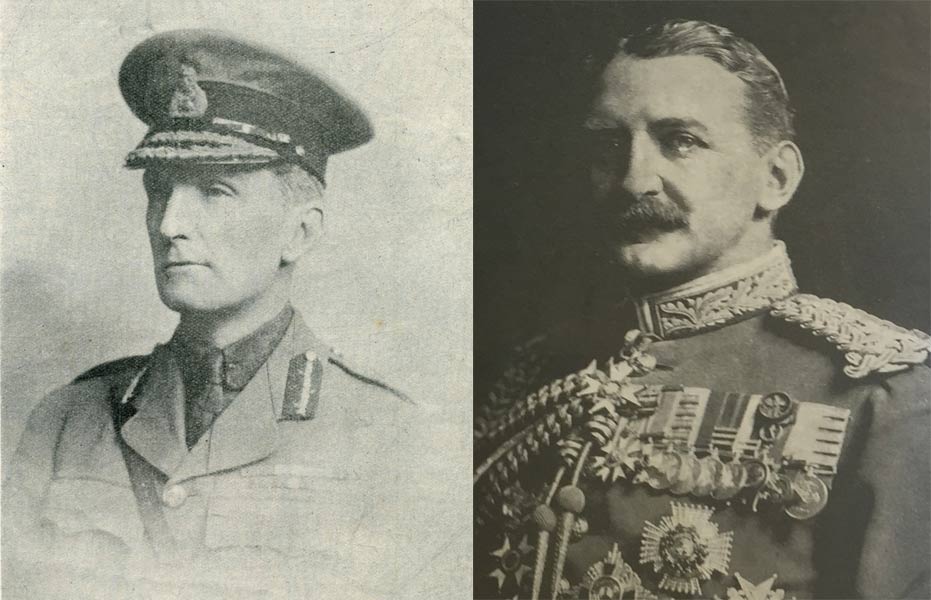

From early Tuesday morning, after his arrival in Dublin from the Curragh, British forces were under the command of General Lowe. Lowe was a veteran of the Boer War and had retired from the army in 1907. He had rejoined at the start of World War One and had been appointed an Inspector of Cavalry and commander of the 3rd Reserve Cavalry Brigade. It was Lowe who would accept the surrender from Patrick Pearse at the end of the Rising. From Friday 28 April Lowe was effectively superseded with the arrival from Britain of General Maxwell. His powers were near absolute as he was acting as a military governor with the full powers of the Defence of the Realm Act available to him. Maxwell would oversee the post-Rising court martial process and the executions of the rebel leadership.

Those British forces stationed in Ireland that were the first to be ordered to act against the Rising were predominantly Irish born, and many of them were volunteers who had signed up to fight against Germany. Despite being at home, these Irishmen were involved in the fighting in Dublin during Easter week, and many paid the ultimate price. As Neil Richardson has shown, 41 of the military deaths in Easter week (or 35%) were Irish born men.

British troops pose for newspaper photographs after the Rising. (Image: UCD Postcards Collection)

Forces brought from Britain

Once the seriousness of the military situation in Dublin became

clear to the British government, it moved quickly to send forces

to the city from Britain. On 25 April the decision was taken to

move large numbers of troops from their training bases in England

and send them to Ireland. They were issued orders on the 25th, and

travelled overnight via Holyhead arriving in Kingstown on the

morning of the 26th.

Those regiments sent to Dublin included the 2nd North Midland Division under the command of Major General Sandbach, the 2nd Lincoln and Leicester Regiment under Brigadier C.G. Blackader, the 2nd Staffordshire Regiment under Brigadier L.R. Carleton and the 2nd Nottingham and Derby Regiment under Colonel E.W.S.K. Maconchy. These various regiments were part of Lord Kitchener’s ‘new army’ that had been recruited from volunteers to fight in World War One. These men were not regular soldiers and most of them had only recently completed their basic training and were awaiting dispatch to France and other theatres of war.

The Regiments from Britain were involved in two of the bloodiest incidents during Easter Week. On the 26 April the 2nd Nottingham and Derby Regiment, made up of battalions from the Sherwood Foresters, marched into the city centre along Northumberland Road. They came under attack from rebels holding 25 Northumberland Road, and it would take a whole day of fighting before the Foresters had successfully taken the rebel positions on Northumberland Road and at Mount Street Bridge. At the close of the day, the Foresters, who had been in Ireland for less than 24 hours, had lost 28 men and over 200 had been wounded. The Sherwood Foresters were typical of them of Kitchener’s ‘new army’ in that the vast majority of them were working class men who had volunteered to fight in World War One. Many of them were young pit workers from the Nottingham coal mines or else operatives in the region’s textile factories. As freshly trained recruits they were unprepared for urban street fighting and their commander’s decisions to keep attacking Mount Street in light of mounting losses undoubtedly led to a higher dead and wounded total.

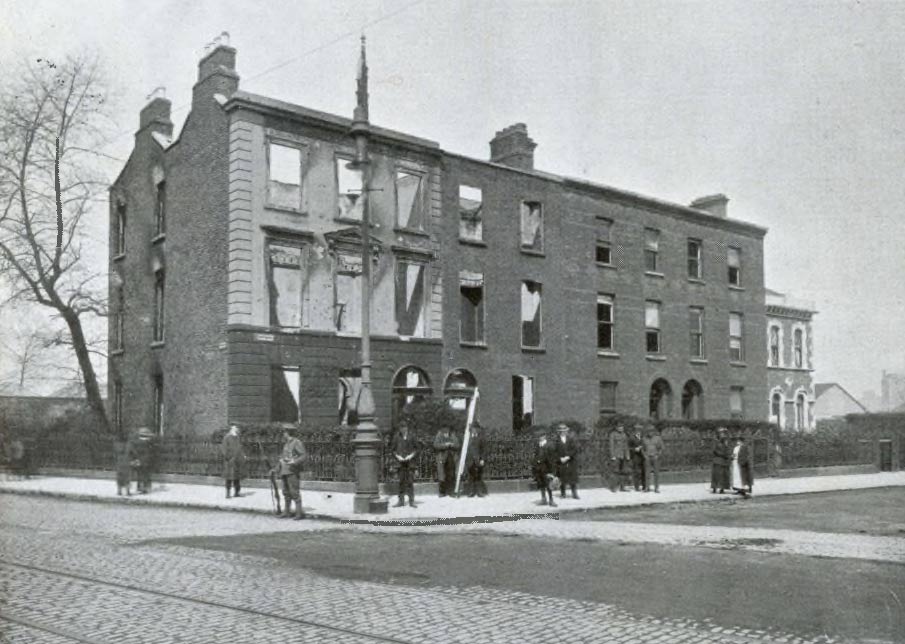

Clanwilliam House facing Mount Street Canal Bridge where the ranks of the Sherwood Foresters were severely thinned by an enfilade from the rebels. (Image: Dublin and the Sinn Féin Rising, Marsh's Library)

The second incident took place on the night of Friday 28 April in the area around North King Street. Here the Volunteers under the command of Ned Daly had put up fierce resistance to the British and had managed to hold the area and cause a high number of casualties. On the Friday evening the South Staffordshire Regiment entered the Street and began clearing the area house by house. The troops were under orders not to take prisoners and took the view that all men in the houses were either rebels or sympathetic to them. In the event the South Staffordshire’s shot or bayoneted 15 men dead. The massacre on North King Street was investigated by a military Court of Enquiry but the decision was made that no one soldier could be held responsible. General Maxwell concluded that for those who were killed, ‘responsibility for their deaths rests with those resisting His Majesty’s troops in the execution of their duty’.

General Lowe (L) was effectively in charge of British military operations in Dublin during the first days of the Rising as he was the most senior officer resident in Ireland on Easter Monday. Command was then taken by General Maxwell (R) after he arrived in Dublin on Friday 29 April. (Images: South Dublin Libraries; A Record of the Irish Rebellion of 1916, Irish Life)

Soldiers' Stories

Each and every person on the streets of Dublin during Easter week

has their own story, and the same is true for those members of the

British military. Two men are chosen here who died during Easter

week in Dublin. They’re chosen not because they are in

anyway individually significant, but rather because they

illustrate the very common decisions that men took during the

period and with no expectation that they would ever end up

fighting on the streets of Dublin in 1916.

Private John Robert Forth

Forth served as a Private in the 2/8th Battalion of the Sherwood

Foresters. He was born in 1898 in Albert Street, Leeds. By the

time Forth was a teenager his parents had moved south to Marecroft

near Worksop which was a mining village. Forth entered the pits at

Manton Colliery on leaving school. In November 1914, still only 16

years old, Forth lied about his age so he could join the patriotic

wave of young men signing up to fight the Germans. Probably

because of his young age Forth was left in training longer than

normal, and spent over a year in barracks in Luton and Watford. In

the spring of 1916 his Battalion was awaiting dispatch to France

when they were loaded onto trains and sent instead to Liverpool

and onto Dublin. Forth landed in Ireland on the morning of the 26

April. His Battalion was marched into the city and passed across

Haddington Road and onto Northumberland Road just after noon. The

Foresters soon came under attack from Volunteers who were

stationed in 25 Northumberland Road. Forth was following his

senior officer, Lieutenant Elliott, when they came under fire.

Elliott was injured, but Forth shot and killed. His local

newspaper, the Worksop Guardian recorded that he met

‘his death most bravely. Forth was 18 years old when he

died. His body was not sent home to Worksop and he was buried at

Grangegorman Military Cemetery in Dublin.

Reginald Clery

At the start of 1915 the Irish Association of Volunteer Training

Corps (IAVTC) was established primarily as a home defence force.

While many of its numbers would leave the home front and fight in

World War One, others, because of age, political opinion or

personal circumstance, stayed in Ireland and took part in the

activities of the IAVTC. On Easter Monday 1916 the IAVTC took part

in a route march away from the city and out to Ticknock. They were

informed of the Rising at 2.30pm and began marching back to the

city. Their destination was Beggar’s Bush Barracks. At

around 4.30pm the returning men of the IAVTC came under fire from

the 3rd Battalion of the Irish Volunteers who were on the railway

bridge on the South Lotts Road. Under fire the IAVTC scrambled

into the Barrack door, but one man had been shot and seriously

wounded. The wounded man was Reginald Clery, a 22 year old

Catholic. Clery had been educated at Belvedere and studied Law at

Trinity. In 1913 he had begun his legal apprenticeship and by 1916

was near to completing his training. Clery was from a military

family, but his education and profession meant that he was the

type of man who would have joined the IAVTC, probably with the

idea, once his professional training was complete, that he would

join up. Clery would die of his injuries a few hours after he was

shot and is buried in the Grangegorman Military Cemetery. On the

War Memorial of his old school Clery is remembered alongside the

only other Old Belvederian to die in the Easter Rising, the

executed signatory of the Proclamation,

Joseph Mary Plunkett.

Further Reading:

Neil Richardson, According to Their Lights. Stories of Irishmen in the British Army, Easter 1916 (Collins Press, 2015).