George Bernard Shaw and the Politics of Possibility

By Ed Mulhall

It is a fine summer’s day. The location is Burren pier on the south shore of Galway Bay. On an ancient stone bollard, an old man sits facing the land. His head is bowed, his face in his hands and he is sobbing. A woman coming up from the sea approaches him and asks whether he needs assistance. She asks him if he is a foreigner and why he is not accompanied by a nurse as it is dangerous for people like him to come to this country at this time because of the deadly disease that they have to protect against. He says he is not a foreigner, but a Briton who now lives in the capital of the British Commonwealth, Baghdad, and he is part of a delegation of the Prime Minister who has arrived to consult the Oracle at a temple in Ennistymon. The year is 3000 A.D.

That is the opening scene of the play Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman by George Bernard Shaw. Soon it becomes clear that the Elderly Gentleman is a ‘short-lifer’, nearing the end of the natural lifespan as we know it and the woman is a secondary, late into her second century with the expectation that she soon will become a tertiary. This long-life race must be protected from the short-lifers and the fatal disease that they can carry. There is no Irish race as they had lost all their distinctiveness once national agitation became redundant and no one wanted to claim affinity with such a barren land. As the Elderly Gentleman recalled:

‘Think of the position of the Irish, who had lost all their political faculties by disuse except that of nationalist agitation, and who owed their position as the most interesting race on earth, solely to their sufferings!’ He said they had travelled the world in search of a cause but lost their appeal: ’the very countries they had set free boycotted them as intolerable bores. The communities which had once idolized them as the incarnation of all that is adorable in the warm heart and witty brain, fled from them as from a pestilence.’ Soon nothing was left for them but to return to Galway Bay but then: ‘the old passionately kissed the soil of Ireland calling on the young to embrace the earth that had borne their ancestors. But the young looked gloomily on and said, “This is no earth only stone” … and all left for England the next day; and no Irishman ever again confessed to being Irish, even to his own children; so that when the generation passed away the Irish race vanished from human knowledge.’

Shaw’s imagining of this distant future is part of his most ambitious sequence of plays, begun in the final months of the First World War at the height of his disillusionment at the horror and futility of the conflict. There were in the end five plays, a Pentateuch, called Back to Methuselah, modelled on Wagner’s Ring cycle and completed in the summer of 1920, when the messy aftermath of the conflict was still being played out all over Europe not least in his home country, and readied to be published and first performed in 1921.

The plays expressed his own frustration with his art, how ineffective he felt his plays and polemics had been in dealing with such a momentous event. This failure had caused him to question his own abilities. He was ageing (64) when he finished the sequence and wondering whether he was applying his talent correctly in trying to craft entertaining vehicles which might blunt his message. But most of all his motivation was to strike back against the inevitability of these disastrous outcomes, that natural selection was an inevitable part of evolution and the sequence of humanity was pre-ordained and inevitable, unswayable by human intellectual intervention. It was thus a challenge to fundamental Darwinism and an argument for another way of thinking about the possibilities for mankind, the concept of Creative Evolution. As Shaw put it: ‘Our will to live depends on hope, for we die of despair or as I have called it in the Methuselah cycle, discouragement.’ So it was this disease of ‘discouragement’ that was the pandemic haunting the future generations on Burren pier.

Shaw had explored this theme before in the Don Juan in Hell act in his very successful play from 1901, Man and Superman:

‘My sands are running out; the exuberance of 1901 has aged into the garrulity of 1920; and the war has been a stern intimation that the matter is not one to be trifled with. I abandon the legend of Don Juan with its erotic associations and go back to the legend of the Garden of Eden. I exploit the eternal interest of the philosopher’s stone which enables men to live forever. I am not, I hope, under more illusion than is humanly inevitable as to the crudity of this my beginning of a bible for Creative Evolution. I am doing the best I can at my age. My powers are waning; but so much the better for those who found me unbearably brilliant when I was in my prime.’

His plays would stretch from the Garden of Eden to the time ‘As far as Thought Can reach’ with staging posts in the politics of the immediate post First World War world, the summer of 2170 and that play set on the Burren in the year 3000 AD. For the published edition of the plays, 100 years ago, Shaw wrote a forceful and closely argued preface called the Infidel Half Century outlining the philosophy behind the drama.

It was a daring undertaking and Shaw was under no illusion as to the risk, but felt he was rich enough to ‘satisfy my evolutionary appetite or “Inspiration” with little prospect of lucrative publication or performance.’ He was not to be disappointed as the plays were rarely produced and then often in a truncated amended version. They divided critics as to their lasting merit but not the ambition as Fintan O’Toole recognised: ‘Back to Methuselah is the first of three early twentieth-century Irish attempts at a sweeping meta-history of humanity, to be followed by W.B. Yeats’s A Vision and James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. In fact, though, it can most usefully be regarded as a harking back to another Irish figure Jonathan Swift. It is Shaw’s attempt at a version of Gulliver’s Travels, a series of voyages, not through imaginary space but through imaginary time. Though far less artistically successful than Swift’s masterpiece, it is intriguing as a kind of reply to it. Shaw’s disgust at the foolishness and depravity of humanity as revealed in war is the same as Swift’s.’

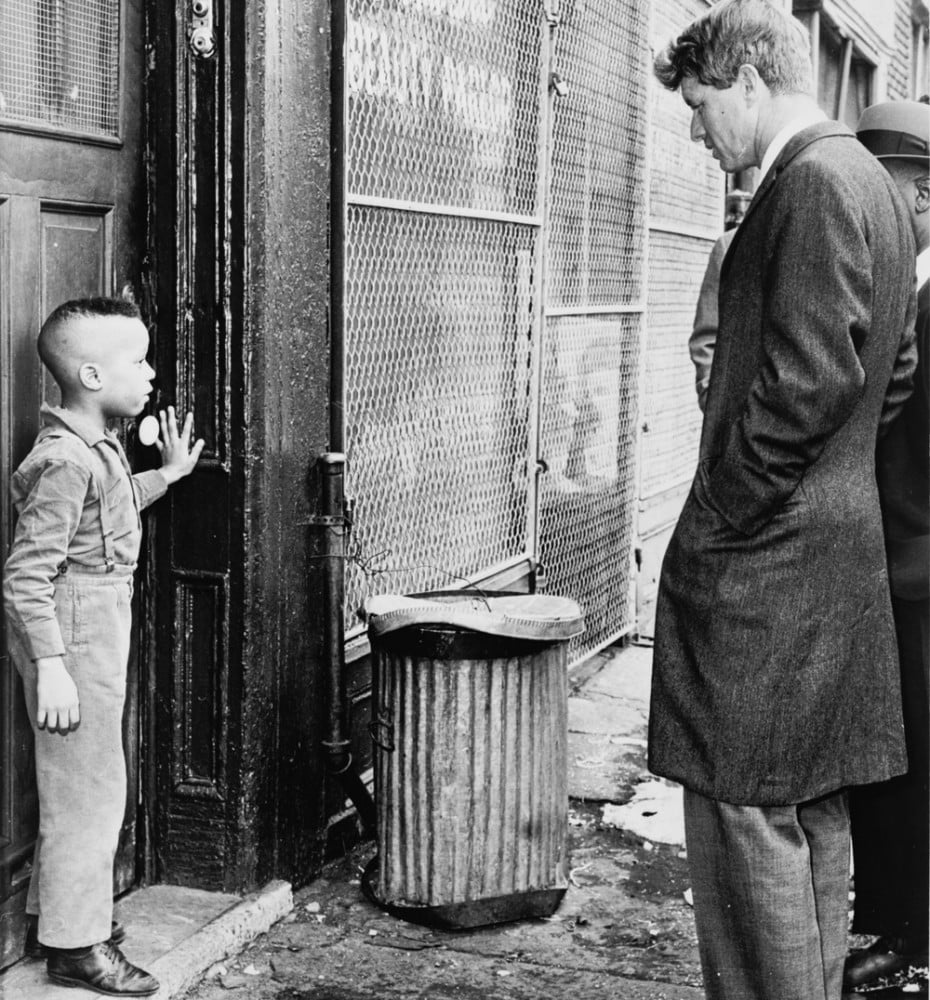

Despite their obscurity the plays had one lasting legacy – a powerful line of political rhetoric that was used by each of the Kennedy brothers to underscore their own politics of possibility. It was to become one of Shaw’s most quoted lines. President John F. Kennedy adapted the line in his speech to Dáil Éireann in his visit to Ireland in 1963. Robert Kennedy used the quote throughout his campaign for the Presidency in 1968, often to end his speeches. And finally it was emotionally used by Ted Kennedy at Robert’s funeral, his voice trembling as he spoke the words so often used by his dead brother. The quote captured the possibilities of political ambition, action and commitment: ‘Some men see things and say, “Why?” But I dream things that never were; and I say, “Why not?”’ Shaw would no doubt have been pleased by the impact and longevity of his phrase and by the irony that in his play this aspiration of possibility is spoken by the Serpent.

John F Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy (pictured), both borrowed the famous line from Shaw in their political speeches - ‘Some men see things and say, “Why?” But I dream of things that never were ; and I say, “Why not?” (Image: Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-133361)

George Bernard Shaw began the play cycle Back to Methuselah in March of 1918, at a time when the First World War was in another perilous phase. There was an armistice on the eastern front, in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, which had facilitated a counter-offensive by the German army on the Somme where they regained significant territory. Close friends of Shaw had been recently bereaved. The actress Stella Campbell’s son Alan had been killed in January. ‘Killed just because people are blasted fools’ Shaw wrote to her on hearing the news. In February, Lady Gregory’s son Robert had died as his plane crashed on the Italian front. He had visited Shaw as recently as July and also featured in a reading of Shaw’s recruitment play O’Flaherty VC, when Shaw visited the front lines.

Originally he conceived the project as a tetralogy using Wagner’s Ring as an example. He was fond of playing extracts from Wagner at this time and no doubt believed the epic scale necessary for his ambition. But when he started writing, it was still recent events that were to the forefront of his mind and in particular the ‘fools’ behind the conflict as he explained to his friend Horace Plunkett in Dublin:

‘I have suddenly buckled to a new play, in which Lloyd George and Asquith will enjoy an Aristophanic immortality… I shall call the play Back to Methuselah. Its theme is that we cannot manage modern civilisation unless we extend the duration of human life and vigour to three hundred years at least.’

This play, later retitled The Gospel of the Brothers Barnabas, was set in a time in the first years after the war and among the main characters were two Prime Ministers. In the same letter Shaw is still advising Plunkett on the then secret final report of the Irish Convention, which was convened by Lloyd George in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising to try and find a solution to Home Rule. Shaw had failed to be nominated to the Convention but had nevertheless tried to contribute plans for a solution through its chairman, Plunkett, and through a series of press articles titled The Matter with Ireland.

The Brothers Barnabas was set in a country house, mirroring that of Shaw’s play set on the eve of war, Heartbreak House. It was written as the pivot point of the sequence setting up the current world as the ‘short-life’ period and establishing characters who would continue into the next phase. ‘The idea is not to get comic relief (they are not really comic when it comes to that); but to exhibit the Church, marriage, the family, and parliament under the shorthand condition before reproducing them under long-lived conditions. The stuttering rector develops (in the next, and futuristic play) into an immoral archbishop and the housemaid into a Minister for Public Something or other.’ Shaw struggled to get the right balance in the play, fighting against it becoming too polemical. He kept revising it up to publication by which time it had gained some post war insights. The war had left: ‘A world without conscience. That is the horror of our condition.’

Central to the satire in the play are two politicians, readily identifiable as Asquith and Lloyd George. George is depicted as the character Joyce Burge who ‘has talked so much that he has lost the power of listening’ and one of the cynical politicians who ‘have managed to kill half Europe between them.’ But the Asquith character, Lupin, is even more severely portrayed. He was hostile to the Suffragettes; he made a deal with the opposition to drop legislation to stay in power when war broke out (a reference to the postponed Home Rule bill) and he played bridge when a key war decision was to be made (a reference the appointment of a successor to Kitchener). Most cuttingly, the Parson in the play says of the wartime politicians that ‘the awful thing about their political incompetence was that they had to kill their own sons.’ Asquith’s son Robert was killed at the Battle of the Somme.

According to one of the brothers, all the politicians and statesmen were culpable: ‘a European group of immature statesmen and monarchs who, doing the very best for your respective countries of which you are capable, succeeded in all but wrecking the civilization of Europe, and did, in effect wipe out of existence many millions of its inhabitants.’ The problem was that it was beyond present human capacity ‘to control powers (of destruction) so gigantic that one shudders at the thought of their being entrusted even to an infinitely experienced and benevolent God, much less to mortal men whose whole life does not last a hundred years...’ It was this last point that provided the kernel of the proposition the play presented as the other brother concluded: ‘It is not absolutely certain that the political and social problems raised by our civilization cannot be solved by mere human mushrooms who decay and die when they are just beginning to have a glimmer of …wisdom..’. In the plays that would follow Shaw tried to imagine a world where this constraint on wisdom was not there, where some could live beyond the current lift span, the long-lifers.

In the next play to be written, the rector and the housemaid from the Barnabas house reappear, but it is 150 years later and as the play title says, The Thing Happens. The scene again is a political one, the official residence of the President of the British Islands. The President seems a composite of the two Prime Ministers in the Brothers play and is called Burge Lupin. In this play, begun in the summer of 1918, the President communicates through a video conference phone with his accountant general, a descendent of the Barnabas brothers, about a new invention which allows people to breathe underwater and prevent accidental drowning. Other characters include the President’s chief secretary, Confucius, an African woman who is the Minister for Health, the Archbishop of York and the Domestic Minister, Mrs Lutestring.

The plot revolves around the startling discovery from film in the Record Office that the victims of a number of infamous drowning incidents, which destroyed many careers, are all actually the same individual who seems to be the current Archbishop of York. When the Archbishop comes to be questioned, he is Rector Haslam from the previous play, still looking just 50 years old, and admits to feigning his death over the years to avoid retirement. His birth certificate had been lost during a bombing raid in the ‘first of the big modern wars’ and he is a long-lifer. It soon transpires that the Minister Mrs Lutestring is another long lifer in hiding and she is known to Haslam as the chambermaid from the time of the Brothers Barnabas. With this secret out, the President and his advisors debate what to do and what the impact will be on society if it becomes known that some of them can live for centuries. A terrible outcome is predicted by Confucius:

‘Every man and woman in the community will begin to count on living for three centuries. Things will happen which you do not foresee: terrible things. The family will dissolve: parents and children will no longer be old and young: brothers and sisters will meet as strangers after a hundred years separation: the ties of blood will lose their innocence. The imagination of men, let loose over the possibilities of three centuries of life, will drive them mad and wreck human society.’

But then comes the realisation that things have changed fundamentally.

The Archbishop and the Minister now know they are not alone with this gift, they will find others like themselves, they will have the wisdom that comes with age and the energy that comes from youth and that ‘they will become a great power.’ The President and his advisors see that there might be the possibility that they too are part of this select group, just not yet old enough to have regenerated. The play ends with the President seeking to keep his options open, refusing a dalliance which required being dropped into Fishguard Bay by the Irish Air Service, in case he develops rheumatism from the cold water. He didn’t want to suffer with it for centuries.

It is this concept of ‘long-lifers’ that is explored in the play set on Burren pier, The Tragedy of an Elderly Gentleman. Begun in May 1918 and written during the period that saw the end of the war and the messy complexity of the peace that followed throughout Europe and in Ireland, Shaw kept revising the play over the next two years right up to publication. At the core of the play is a dialogue between the short-lifers such as the Elderly Gentleman and the Presidential entourage (which includes a general, representing Cain, called Napoleon) and the long-lifers and their Oracle. The delegation has come to the west of Ireland, a place of pilgrimage for those seeking “mental flexibility”, in order to consult the Oracle. The Oracle and the long-lifers of authority and influence present are all female.

While the long-lifers are seen to have youth, health and wisdom, they are stern and devoid of some other human characteristics like a sense of humour or irony.

The Elderly Gentleman tries to defend his civilisation by pointing to the great ancient teachers of his civilisation and those who fought for Christ-like principles throughout the 20th Century. This is dismissed by a long-lifer called Zoo:

‘But did any of their disciples ever succeed in governing you for a single day on their Christ-like principles? It is not enough to know what is good; you must be able to do it…You know very well that they could only keep order – such as it was – by the very coercion and militarism they were denouncing and deploring. They had actually to kill one another for preaching their own gospel or to be killed themselves.’

The history that followed the war to end war is described in stark terms:

‘All I can tell you about it is that a thousand years ago there was a war called the War to end War. In the war which followed it about ten years later, hardly any soldiers were killed but seven of the capital cities of Europe were wiped out of existence. It seems to have been a great joke; for the statesmen who thought they had sent ten million common men to their deaths were themselves blown into fragments with their houses and families, while the ten million men lay snugly in the caves they had dug for themselves. Later on even the houses escaped; but their inhabitants were poisoned by gas that spared no living soul. Of course the soldiers starved and ran wild; and that was the end of the pseudo-Christian civilisation. The last civilized thing that happed was the statesmen discovered that cowardice was a great patriotic virtue and a public monument was erected to its first preacher, an ancient and very fat sage called Sir John Falstaff.’

The delegation want to know how the technology developed that allowed wars to be won so they could keep ahead of their rivals in case a dispute arose. The reply from a long-lifer attested to the recurring cycles of history:

‘you can make the gases for yourself when your chemists find out how. Then you will do as you did before: poison each other until there are no more chemists left, and no civilisation. You will then begin all over again as half-starved ignorant savages, and fight with boomerangs and poisoned arrows until you work up to poisoned gases and high explosives once more, with the same result. That is, unless we have sense enough to make an end of this ridiculous game by destroying you.’

The play is more a parable than a work of science fiction, though there are some interesting little details: they communicate through wireless technology – a tuning fork; a force field is used to restrain people and a video representation of the Oracle appears in the air.

The play concludes with the delegation returning home to lie about the answers they have been given. It is a deception the Elderly Gentleman wants no part of and he seeks to remain in Ireland amongst the long-lifers despite the dangers of the disease of discouragement, saying that if he returned home he would die anyway of ‘disgust and despair.’ He is granted leave to stay but dies at the touch of the Oracle: ‘Poor short-lived thing what else could I do.’

Having conceived of the sequence of plays in the midst of war, it was in the aftermath of the armistice and the 1918 election that Shaw focussed on the opening play located in the Garden of Eden. Called In the Beginning, it was in two acts, the first featuring Adam and Eve and the temptation of the Serpent, the second a few centuries later when their son Cain returns from having killed his brother and invented warfare.

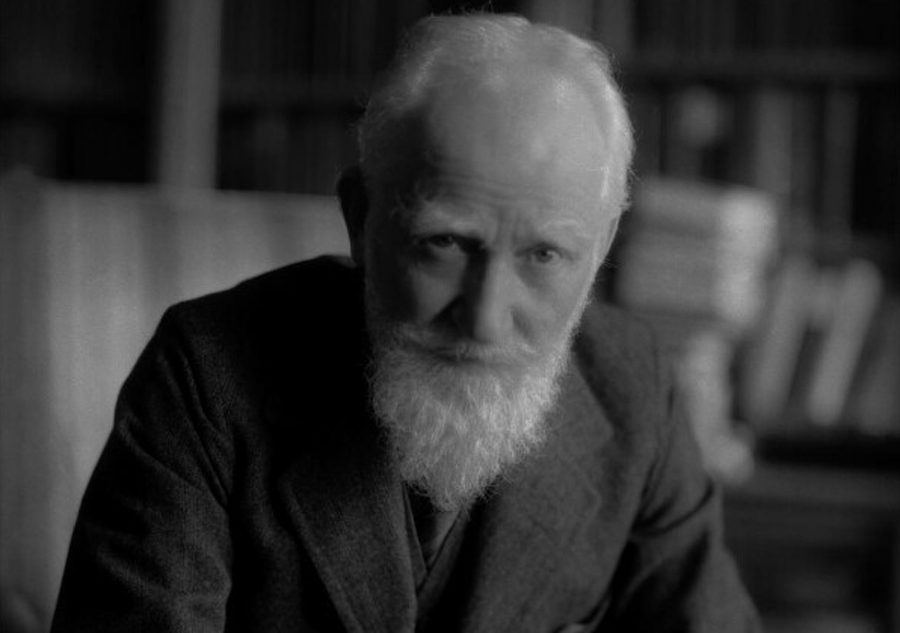

George Bernard Shaw is interviewed in 1937

It contains some of Shaw’s most powerful writing as Adam and Eve learn from the Serpent the fundamental words of life. The Serpent first teaches them about Death and then about Birth:

‘THE SERPENT: The serpent never dies. Some day you shall see me come out of this beautiful skin, a new snake with a new and lovelier skin. That is birth.

EVE: I have seen that it is wonderful.

THE SERPENT: If I can do that, what can I not do? I tell you I am very subtle. When you and Adam talk, I hear you say “Why?” Always, “Why?” But I dream things that never were; and I say “Why not?” I made the word dead to describe my old skin that I cast when I am renewed. I call that renewal being born’

Eve and Adam then learn other words from the Serpent: ‘life’, ‘miracles’, ‘imagining’, ‘practice’, ‘conceive’, ‘mother’, ‘immortality’, ‘procrastination’, ‘strangers’, ‘kill’, ‘Love’, ‘jealousy’, ‘fear’, ‘hope’, ‘vows’, ‘wife’ and ‘husband’. They are told: ‘As long as you do not know the future you do not know that it will not be happier than the past. That is hope.’ Laughter is ‘the noise that takes away fear’.

Having made their vows to each other Adam leaves Eve to hear from the Serpent the secret that will bind them together:

‘EVE: Now the secret. The secret. (She sits on the rock and throws her arms around the Serpent who begins whispering to her)

Eve’s face lights up with intense interest, which increases until an expression of overwhelming repugnance takes its place. She buries her face in her hands.’

In the second act, set a few centuries later in an oasis in Mesopotamia, Adam digs a garden, Eve spins flax and their son arrives carrying a spear and shield. Cain is taken as representing militarism, having invented murder and warfare by killing Abel. He is the conqueror of danger and fear with the courage to fight to the end: ‘Death is not really death... it is the gate of another life: a life infinitely splendid and intense: a life of the soul alone…’

The clash is with his mother Eve who fears that through him and his like death is gaining on life: ‘Already most of our grandchildren die before they have sense enough to know how to live. Man… need not always live by bread alone.’

As he worked on the plays Shaw read them to a select group of friends, among them Lady Gregory:

‘Last night at Lamer he gave an account of a wonderful and fantastic play he is writing beginning in the Garden of Eden, before Adam and Eve, with Lilith who finds a lonely immortality impossible to face and so gives herself up to be divided into Man and Woman. He had read me a scene in it (on the pier at Burren) about a thousand years in the future with the Irish coming back to kiss the earth of Ireland and not liking it when they see it.’

She captured the intensity with which Shaw was working away on his typewriter

‘I told GBS that I had heard the cheerful little ticking of his typewriter like chickens picking their way out of the egg and had listened with joy as I used to do when I heard a purring from Yeats’ room.’

Shaw later read her a draft of the first play:

‘GBS read me his play beginning in the Garden of Eden. The first act is a fine thing, “a Resurrection play” I called it. The second, 200 years later, an argument between Cain, Adam and Eve, the soldier against the man of peace. I told him I thought it rather monotonous, an Ossianic dialogue, and he said he thought of introducing Cain’s wife “the Modern Woman” or perhaps only speaking of her in the argument.’

Shaw continued to work on the draft throughout 1919 and to expand its scope.

What he originally envisaged as a series that might be performed in one long evening had now expanded into something greater with now a final fifth play.

Set in the year 31,920 AD it was called AS FAR AS THOUGHT CAN REACH. It is written in the style of the ancient Greek plays with some characters representing categories such as the new-born, the newly ancient, the youth etc. But the main section involves the return of Adam, Eve and the Serpent and their questioning by Lilith, who in some legends preceded Eve but, in Shaw’s imagining, is the forerunner of Adam and Eve who willed man and woman into existence. Lilith has the final words of the epic:

‘I am Lilith: I brought life into the whirlpool of force, and compelled my enemy, Matter, to obey a living soul. But in enslaving Life’s enemy I made him Life’s master; for that is the end of all slavery; and now I shall see the slave set free and the enemy reconciled, the whirlpool become all life and no matter. And because these infants that call themselves ancients are reaching out towards that, I will have patience with them still; though I know well that when they attain it, they shall become one with me and supersede me, and Lilith will be only a legend and a lay that has lost its meaning. Of Life only there is no end; and through all of its million starry mansions many are empty and many still unbuilt, and though its vast domain is a yet unbearably desert, my seed shall one day fill it and master its matter to its uttermost confines. And for what may be beyond, the eyesight of Lilith is too short. It is enough that there is a beyond. (she vanishes)’

As well as writing the last play Shaw spent the first half of 1920 preparing a lengthy preface outlining the philosophy behind the work.

In the preface which he called The Infidel Half Century he outlined the basic philosophy behind the plays, the concept of Creative Evolution, challenging what he describes as the pessimism of Darwinian Natural Selection, where the fittest survive and patterns of evolution are seen as inevitable and unalterable:

‘...my creed of creative evolution means in practice that man can change himself to meet every vital need and that however long the trials and frequent the failures may be, we can put up a soul as an athlete puts up a muscle. Thus, to men who are themselves cynical I am a pessimist, but to genuinely religious men I am an optimist, and even a fantastic and extravagant one.’

Shaw’s biographer sees this as a view consistent with the rational thinking that preceded him: ‘Shaw called for the same sort of admission that Copernicus, Galileo and Darwin had demanded. He too removed human beings from their central position as unique instruments through which a divine will operated but he restored to them their own will…(and) restored the value of instinct and intelligence as controls for human destiny.’

Shaw had originally developed his theory in a lecture on Darwin and an essay on the philosopher Samuel Butler some 30 years previously. He argued that it was too crude to assume that the present was determined by the past and it in turn would determine the future. ‘The true view is that the future determines the present. If you take a ticket to Milford Haven you will not do so because you were in Swansea yesterday but because you want to be in Milford Haven tomorrow.’ It was an argument in favour of the responsibility that each generation has to take care of the planet, that they must look beyond their own life span. He saw science not as something mechanical solely dependent on laboratory experiment, but which encompassed the potential for a leap of imagination as shown by the example of Leonardo da Vinci. As man’s life span was too short to observe the ‘organic’ pattern of evolution Shaw used instead the timescale of his imagination to frame his concept. It had the added benefit that it chimed with his own experience at the time facing into old age as he explained to his friend, the Irish playwright, John Ervine:

‘There are things that I cannot do that I could do years ago; but there are also things that I was never clear about years ago that I am quite clear about now. I am still growing whilst I am decaying, it is the physical decay with its reduction of my powers of endurance in every department that is beating me and presently will kill me. When a man dies of old age, he kills a lot of mental babies with which he is pregnant.’

The final work on the drafts and the preface was done in Ireland, in the Great Southern Hotel in Parknasilla, Kenmare from July 1920. There was evidence of the War of Independence around him, with ‘the barracks are all burnt’, and most notably by the absence of police and order in Kerry maintained by Sinn Féin volunteers.

The Great Southern Hotel, Parknasilla, where Shaw completed his ‘magnus opus’ in late 1920. (Image: National Library of Ireland, L_ROY_11090)

On the 15th September, he sent his ‘magnum opus’ of five plays and a ‘colossal preface’ to the printers. He was already realistic with his expectations for the work: (it) ‘may not be worth translating as far as the theatre is concerned as, though it is a single work, it consists of five long plays, all quite impossible except for a very thoughtful and advanced audience. But it will be good reading.’

It was not until the following summer that Shaw had copies of the book to distribute. Lady Gregory was visiting him in England when she got her copy:

‘I read the Preface to Methuselah this morning – the ‘nine months of gestation’ ... and he read the last act tonight, a history of the race – a philosophy of its life – terrible in parts but leading to the freedom and life of the spirit at the last. He had tried to humanise his people, wrote a sort of domestic drama as a continuation of Eden, but Granville Barker said it was wrong and he saw then that he must keep to this subject of the continuance of life…. This morning when I went down, I said to GBS ‘I am happy to find that in spite of having travelled through the ages in your play I was still able to say my prayers.’

During that summer of 1921 he sent copies of the book to a wide variety of friends and associates. Among them the Russian leader, Vladimir Lenin, who marked some passages approvingly “bien dit” and other ‘more utopian‘ passages with marks of disapproval. As he was sending out these copies, he was also responding to a circular from Sylvia Beach in Paris seeking subscriptions for James Joyce’s Ulysses which she hoped to publish soon. Shaw replied that he had read the extracts to the novel that had been appearing in the Little Review since and described it as a ‘revolting record of a disgusting phase of civilisation but it is a truthful one’. It is interesting to speculate whether the ambition seen in those extracts of Ulysses in the Little Review had any impact on Shaw stretching his own faculties in Methuselah. If so, there is a strange symmetry as scholars have found many reference points to Shaw’s Methuselah in Joyce’s next work Finnegans Wake, where he too takes on the history of mankind from its origins to a time as far as the human mind can imagine and maybe beyond. The book of Back to Methuselah sold well, better than any other of his works he told his translator and received great endorsement from influential critics like Max Beerbohm.

Others like TS Elliot who was completing his own magnum opus, The Waste Land, felt that Shaw was squandering his powerful dramatic gifts of wit and acute observation in the service of ‘worn out home-made theories’. And Lady Gregory witnessed a mixed reception when Shaw read from the play in the Abbey Theatre:

“GBS gave his lecture for the Abbey and read two acts of his new play Back to Methuselah, and some of the audience were pleased, others would have liked a continuation of his lecture, Lady Gough fell asleep. The play read well, the bit about the feeding on the heavenly manna very fine, Dr Monro’s idea is in the phrase ‘imagine to create’.”

Despite his pessimism that his plays would never be performed, in early 1922 the American Theatre Guild performed them in three-week cycles with over 25 full sequences completed in the nine week run. It was a box office failure but a success in adding membership to the Guild. In England, the Birmingham Repertory Company took on the challenge in the autumn of 1923 with a run in Birmingham and in the Royal Court Theatre in London the following year. Among the cast was Edith Evans at the start of what would turn out to be a legendary career playing the part of the Serpent, the Oracle and the She-Ancient. Shaw was delighted to attend the first night in London ’This has been the most extraordinary experience of my life.’ The full set of plays were first performed in Ireland in the Gate Theatre in the winter of 1930 as one of the first productions of Edwards and MacLiammóir – it was directed by Hilton Edwards with sets by Micheál MacLiammóir. “The challenge for the cast was made clear by MacLiammóir to a Daily Express reporter: “Never know whether I’m rehearsing Confucius or the Snake! We rehearse all day and we act at night. When we go home we learn our lines for the next play. Besides rehearsing ourselves, Hilton is directing, and I am designing scenes and costumes, and haranguing scene-shifters.” As well as directing Hilton Edwards played the part of the Elderly Gentleman in the fourth play. The plays were sometimes put on as single plays, particularly the first Eden play, but rarely produced in full. After Shaw’s death the American Guild revived the plays in an abridged version with the Hollywood leading man, Tyrone Power, in the last year of his life playing Adam, the Rev Haslam, the Archbishop and The Ancient.

The book was published in 1921 simultaneously by Constable in London and Bretanol in New York. Shaw was just 65 and already felt that his ‘career as an imaginative writer was finished and that Back to Methuselah would be my swan song.’ But in keeping with his theme, age hadn’t eroded his skills as yet. The completion of his big work had opened up the possibility of new ones and he began what would become one of his most enduring plays, Saint Joan. For Lady Gregory, who again was one of the first to hear its opening act, it had given him a new artistic vigour:

‘In all the revision of novels and business letters of these last years, he had felt as if his imagination had vanished, that he was “done”. And now in the discovery that he writes as well as ever he has grown young again, looks better than for years past, though complaining of aches and pains from sawing of wood, to which he has taken for exercise.’

Saint Joan was one of Shaw’s most successful plays and helped him win the Nobel Prize for Literature. In his presentation speech, in December 1926, Per Hallström, Chairman of the Nobel Committee saw a progression from Methuselah to Saint Joan:

‘In Back to Methuselah (1921) he achieved an introductory essay that was even more brilliant than usual, but his dramatic presentation of the thesis, that man must have his natural age doubled many times over in order to acquire enough sense to manage his world, furnished but little hope and little joy. It looked as if the writer of the play had hypertrophied his wealth of ideas to the great injury of his power of organic creation.

But then came Saint Joan (1923), which showed this man of surprises at the height of his power as a poet…. If from this point we look back on Shaw’s best works, we find it easier in many places, beneath all his sportiveness and defiance, to discern something of the same idealism that has found expression in the heroic figure of Saint Joan. His criticism of society and his perspective of its course of development may have appeared too nakedly logical, too hastily thought out, too inorganically simplified; but his struggle against traditional conceptions that rest on no solid basis and against traditional feelings that are either spurious or only half genuine, have borne witness to the loftiness of his aims. Still more striking is his humanity; and the virtues to which he has paid homage in his unemotional way – spiritual freedom, honesty, courage, and clearness of thought – have had so very few stout champions in our times.”

Ever argumentative, Shaw sought to have the final word on Methuselah and in 1944 in the middle of another World War revised both the Preface and the play and in an unusual departure added a Postscript. With planned publication to coincide with his 90th birthday in 1946, Oxford University Press had asked him to choose from his works the 500th title in their Worlds Classic Series. He chose Back to Methuselah. The intervening period had seen Shaw’s own reputation suffer with inconsistent and at times erratic and misguided political commentary and little new dramatic work of enduring impact. There was a growing disconnect with the sceptical, compassionate, patient and optimistic Shaw that had written these plays. A theory that wisdom came with age was under serious stress in his own example.

READ: Back to Methuselah by George Bernard Shaw via Internet Archive

As Fintan O’Toole concluded Shaw’s real failure was ‘not that he prefigured the use of political mass murder in the twentieth century but that he was unable to recognise it when it happened. The great seer failed to see the true nature of fascism, Nazism and Stalinism. The great sceptic allowed himself to believe just what he wanted to believe, that the totalitarian regimes of Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin were rough harbingers of real progress and true democracy. GBS was by no means the only artist or intellectual to be deluded by the promise of regimes that ‘got things done’ while democracies struggled to end the Great Depression. But no other artist or intellectual had his standing as a global sage. His sagacity proved to be useless when it mattered most.’

In the shadow of this failure and in a destructive war that still had a year to run Shaw returned to Methuselah and tried to reclaim the higher ground of possibility. He recognised his own frailty, in his then 89th year:

‘Physically I am failing: my senses, my locomotive powers, my memory are decaying at a rate which threatens to make a Studldbrug of me if I persist in living; yet my mind still feels capable of growth; for my curiosity is keener than ever. My soul goes marching on; and if the Life Force would give me a body as durable as my mind, and I knew better how to feed and lodge and dress and behave, I might begin a political career and evolve into a capable Cabinet minister in a hundred years or so…’

Seeing the world again in a destructive conflict brought him back to fundamental principles:

‘We must not stay as we are, doing always what was done last time, or we shall stick in the mud. Yet neither must be undertake a new world as catastrophic Utopians, and wreck our civilization in our hurry to mend it.’ Science should not stand on its own: ‘Professional science must cease to mean the nonsense of Weisman and the atrocities of Pavlov in which life is a purposeless series of accidents and reflexes and logic only a thoughtless association of ideas….It must renounce magic and yet accept miracle: for as biology is still in the metaphysical age (all its new knowledge of chromosomes and hormones only substitutes millions of miracles for the single mystery formerly called the soul or breath of life); and as physics, in spite of its miraculous electrons and its abolition of matter, is nearer to the positive stage, the metaphysicians and artist-philosophers must co-operate with the astronomers and physiologists in separate but friendly and at the edges overlapping departments of social service. Both are trying to see a little farther into the dark; and whether the electronic microscope or the philosopher’s brain has pierced it farthest is not worth quarrelling about; for the darkness beyond still forces us to tolerate both microscopic revelation and metaphysical speculation with all its guesses and hypotheses and dramatizations of how far thought can reach….’

The argument made, Shaw ended his Worlds Classic Postscript with a typical closing flourish:

‘Discouragement does in fact mean death; and it is better to cling to the hoariest of the savage old creator-idols, however diabolically vindictive, than to abandon all hope in a world of ‘angry-apes’, and perish in despair like Shakespeare’s Timon. Goethe rescued us from this horror with his “Eternal Feminine that draws us forward and upward” which was the first modern manifesto of the mysterious force of creative evolution. That is what made Faust a world classic. If it does not do the same for this attempt of mine, throw the book in the fire; for Methuselah is a world classic or it is nothing.’

2021 marks another milestone as the work of George Bernard Shaw entered the public domain, 70 years after his death in November 1950. This was the effective end of his very significant bequest to the National Gallery of Ireland which had purchased paintings over those years from their share in his royalties.

But it could also bring new opportunities for adapting, staging and publishing his works.

Today, 100 years after the completion of these plays, as the world is again confronting the perils of its interconnectedness and division, there may be some merit in considering these parables of possibility and the enduring power of imagination.

To again take the challenge of the Serpent’s question, why

not? And his subsequent admonition to Eve: ‘Do, Dare it.

Everything is possible: everything.’

Ed Mullhall is a former Managing Director of RTÉ News

& Current Affairs and Editorial Advisor to Century

Ireland