Return to Ithaca – How Joyce completed Ulysses

By Ed Mulhall

It was in a dancehall called Bal Bullier in Montparnasse in Paris that the artist Arthur Power first met James Joyce.

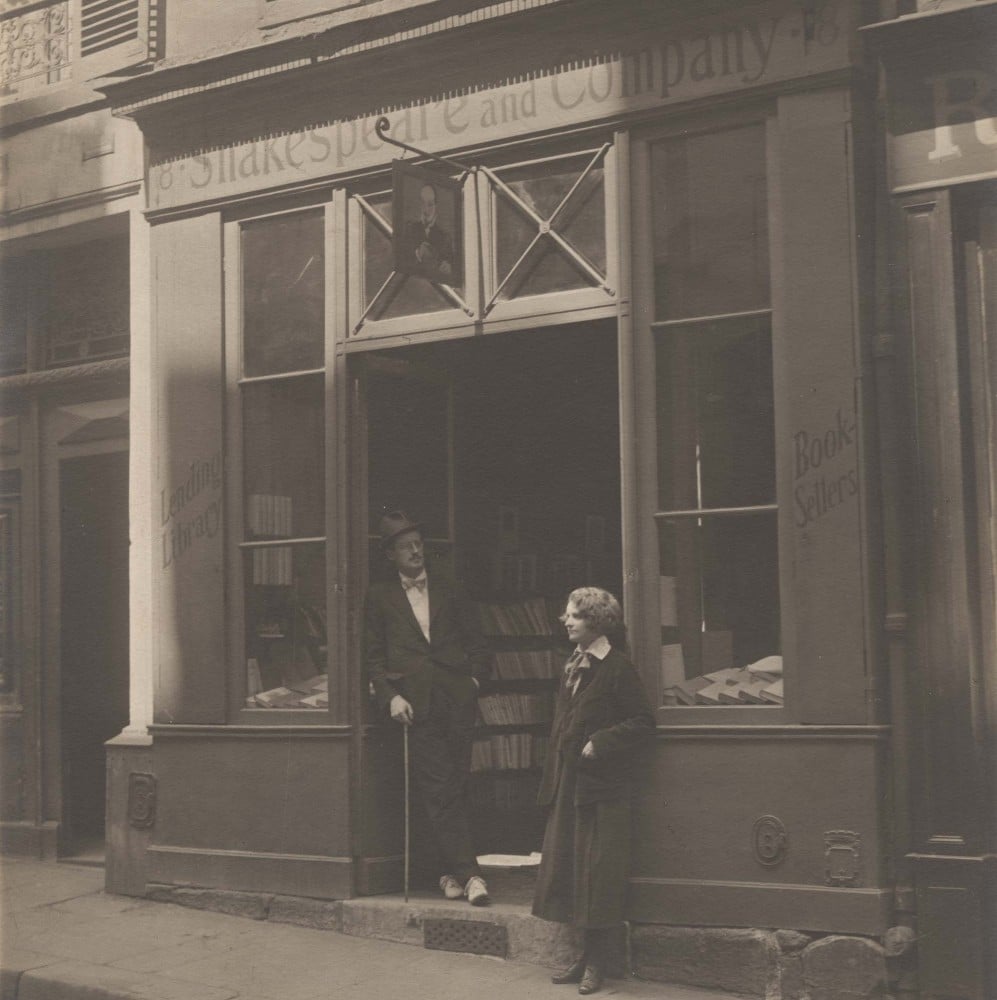

It was a Saturday night in early April 1921 when Power was called over to Joyce’s table to be introduced to the author, who was always keen to meet someone from Dublin. As with all accounts of such meetings, Joyce was full of questions. Power recalled: ‘He asked if I came from Dublin, seemed pleased when I told him I did, and asked how long had I left and who had I known there. These questions didn’t altogether please me, for I had gone to Paris to forget Ireland as a whole, and my native Dublin in particular.’ Their dialogue was interrupted by a ‘young American woman at the table, Miss Sylvia Beach, who proposed we should fill our glasses and drink a toast to the success of James Joyce’s new book, Ulysses.’ The toast celebrated a significant moment in literary history as earlier that day Beach and Joyce had formally agreed that her bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, would become the first publishers of Ulysses. After the celebration Joyce and Power went across the road for a final drink where Joyce told him of the difficulties he had in finding a publisher for the novel it had taken him eight years to write.

It had been a traumatic week for Joyce.

He had just learned that the editors of the Little Review, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, had lost their ‘obscenity’ trial at the New York Court of Special Sessions, receiving a fine of $50 each and being prohibited from publishing any further extracts from Ulysses in their magazine. Beach had given him a clipping of the New York Tribune and Joyce had gone to an American bank to transcribe the story and other coverage of the trial. But as he wrote to his benefactor and English publisher Harriet Shaw Weaver: ‘the trial took place on February 21st it seems. Since that time no person in New York has sent me a word of information on the subject’. Weaver had herself just learned of the verdict from the American publisher, Ben Huebsch. Huebsch had an agreement with Joyce and Weaver, arranged by the lawyer John Quinn, to publish Ulysses in the US (with Weaver following in the UK). But he (Huebsch) now said this was impossible unless cuts were made to the text. Weaver forwarded the letter to Joyce and Joyce immediately cabled John Quinn to ‘withdraw the entire typescript’ from Hubesch and cancel any arrangement to publish in the US. Quinn had represented Anderson and Heap at the trial and it was a number of days later before he sent Joyce his own account of the proceedings.

With the Huebsch option gone, so were Weaver’s plans for an English edition. She had discussed using the English poet John Rodker’s hand press in Paris but needed the American galleys as a backup. Ulysses was without a publisher. It was then that Sylvia Beach made her formal offer which Joyce accepted. Beach said that Joyce had told her ‘my book will never come out now’, pronouncing it as ‘buk’as she recounted in an interview for Teilifís Éireann. She then asked him: ‘Would you let Shakespeare and Company have the honour of bringing out your Ulysses?’ Though in her memoir Beach has this as a spontaneous offering, earlier accounts from her indicate that the original suggestion came from Joyce and Beach made the formal proposal following discussion with Adrienne Monnier.The excitement of that week is captured in a letter from Beach to her mother begun on April 1st: ‘Mother dear it’s more of a success every day and soon you may hear of us as regular Publishers and of the most important book of the age…shuuuuuuu... it’s a secret…’ It seems that the letter was not sent immediately as a P.S. was added later in the week: ‘P.S. It’s decided I’m going to publish ‘Ulysses’... in October…!!! Ulysses means thousands of dollars of subscriptions to be sent to Shakespeare and Company at once.’ In the interval Beach had sent Joyce a formal prospectus for the publication on April 7th prepared with the assistance of her close friend, Adrienne Monnier, whose bookshop was on Rue de l’Odeon. (Beach would move Shakespeare and Company to a location opposite in July.) ‘Adrienne Monnier helped me with it and as she has some experience in that sort of thing you can trust her not to make any mistakes.’

Joyce gave the details to Weaver in a letter confirming his cancellation of the US arrangements:

‘The proposal is to publish here in October an edition (complete) of the book so made up:

100 copies on Holland handmade paper at 350 frs (signed)

150 copies on verge d’arches at 250 frs

750 copies on linen at 150 frs

That is, 1000 copies with 20 copies extra for libraries and press.

A prospectus will be sent out next week inviting subscriptions…They offer me 60% of the net profit...’

Joyce recommended that Weaver’s plans for an English edition be amalgamated with this proposal as the most viable option. He had already sent material for trial proofs to the printer who was ready to begin as soon as the number of orders covered approximately the cost of printing. The printer in question was Monnier’s recommendation – Maurice Darantiere.

Just as Beach and Joyce were formalising their agreement another crisis had emerged. Circe was in flames. Circe, the episode set in the Nightown district of Dublin, had proven to be the most troublesome episode for Joyce to write. It had taken over 6 months (June to December 1920) and he estimated 9 drafts. He then had a series of difficulties getting the manuscript typed. It was not just the length and complexity of the episode but the nature of the content that was causing problems. Even before agreeing to publish the book Beach had been arranging for a series of typists (including her younger sister Cyprian who was in Paris) to work on the drafts. After one typist had to withdraw due to the illness of her father, the next one had problems of a different kind. As Joyce wrote to Weaver on April 9th: ‘Last night at 6 o’clock Mrs Harrison, to whom the final scenes of Circe had been passed on for typing after the accident to Dr Livisier, called on me in a state of great agitation and told me that her husband, employed in the British Embassy here, had found the MS, read it and then torn it up and burned it. I tried to get the facts from her but it was very difficult. She told me that he had burnt only part and the rest was “hidden”.’ Before he left for the meeting with Beach at the dancehall on the Saturday evening he had learnt that the missing section was not as great as he had feared after ‘twenty four hours of suspense’. He told Weaver that there were just a few pages missing which he would have to try and recreate from notes. This would not be easy as since writing the section he had written the end of Circe as well as ‘all the Eumaeus episode and a good part of Ithaca.’

Following consultation with Weaver and Beach he wrote to John Quinn to see if he could help recover the missing section. ‘What I am concerned with’ he explained, ‘is that there is now a lacuna of several pages in the typescript, which has already gone to the printer and I must write it in. Unfortunately I had sent you the MS a few days before (the MS burnt was a copy of my MS made by Miss Beach). I need about six or seven pages back again for a day or so and will return them registered…May I ask you to lend them to me?.’ He gave some indication of the missing section: ‘It begins about p. 60 or so, where Bloom leaves the brothel; there is a scene on the steps and then a hue and cry in the street and the beginning of the quarrel with the soldiers. Six or seven pages after Bloom’s exit (which you will find at a glance by the long catalogue of the persons in pursuit) will suffice.’ Joyce had even sent Quinn an early draft of Circe as a bonus (now in the National Library of Ireland) with the full fair copy, but Quinn, replying in a stance reminiscent of his failed defence of the Little Review, indicated that he had some sympathy for the husband and felt that the wife should have been pleased with what he did ‘shielding her, protecting her, guarding her, and learning what she was doing and disapproving where disapproval was due’. Still, ever protective of his own investment, and having prevaricated for some time, he eventually sent photographic copies of the section a month later. Joyce, who had received Quinn’s account of the Review defence and accompanying affidavits, incorporated some of the content into his revision of Circe, never wasting a new source.

Unlike Beach, Adrienne Monnier had experience in publishing with her own imprint La Maison des Amis des Livres, which would later publish the first French translation of Ulysses by Auguste Morel. She always worked with Maurice Darantiere, a ‘master printer’ based in Dijon, some 260 kilometres from Paris, who specialised in limited editions as well as general publications. He used hand-presses for these special editions to ‘keep that tradition alive’ as well as having modern presses for the larger numbers. Most importantly, in Darantiere, Beach had found a printer undeterred by the controversial content and willing to be flexible right up until publication day, accepting late payments and in particular incorporating changes and additions to the text on the proofs and galleys. As Beach wrote: ‘So the dignified printing house of M. Maurice Darantiere was in a bustle. The quiet town of Dijon, which produced mustard, ‘Glory’ roses and candied black currants in liqueur, had now another speciality – Ulysses.’

As explained by Joyce to Weaver, the financing of the printing was

dependent on gathering paid subscriptions for the various

editions. The prospectus which outlined the proposal contained, as

a key component, quotes from the press about Joyce and other

notable recommendations on Monnier’s advice: ‘She says

the extracts from the press are very essential and that the stuff

about payment is of great importance.’ Payment was important

for Joyce too. He had been expecting an advance from Quinn and

Huebsch in relation to the now cancelled U.S. edition and asked

Weaver if something could be arranged between her and Beach for

advances in respect of the UK orders or sales. Weaver, who was

enthusiastic in correspondence with Beach about the new publishing

plan, responded that rather than amalgamating the editions, she

had drawn up a new contract for a subsequent English publication

using the Dijon sheets. For this she proposed that Joyce would

receive an immediate advance of £200, 25% of the proceeds

from the English edition until expenses were covered and then 90%

of the profits. Joyce agreed immediately by telegram. Weaver asked

Beach for seven hundred to a thousand copies of her prospectus

which she would send to the Egoist subscribers and Irish

and American bookshops with ‘a slip that all applications

should be sent immediately to Paris.’ In the United States

similarly, the editors of the Little Review, Margaret

Anderson and Jane Heap, were proactive in promoting the prospectus

with a full page advertisement encouraging subscribers.

The advances from Weaver proved to be vital for Joyce.

The intention from Beach had been to receive the money for subscriptions well in advance but most subscriptions were not paid until the book was in print and payment was required before despatch. The subscription campaign launched by Beach was however an extensive one. The form printed by Darantiere announced that Ulysses would be ‘complete as written’ – an important guarantee for Beach. Eric Bulson, in his Ulysses by Numbers book, has calculated that two thousand copies of the prospectus were dispatched in mid-May, with another thousand in July and a further thousand in late December. Joyce gave then an exaggerated figure of 5,000 to Weaver in August from which he said there was ‘a capture’ of just 260. Joyce had himself prepared lists for Beach, one list of 67 of his own contacts (including 5 in Ireland) and a second list of 78 mainly suggested reviewers, libraries and others who might publicise the novel. From these combined numbers, Bulson estimated that just 40 eventually received copies, concluding: ‘if nothing more these numbers prove that Joyce was better suited at writing his novel than he was at finding readers for it.’

James Joyce and Sylvia Beach outside Shakespeare and Company (Image: Courtesy of the Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York)

Joyce though did follow the subscriptions closely in Beach’s new premises on Rue de l’Odéon: ‘Something really comic could be written about the subscribers to my tome – a son or nephew of Bela Kun, the British Minister of War Winston Churchill, an Anglican bishop and a leader of the Irish revolutionary movement.’ The latter was Desmond Fitzgerald whose wife Mabel prompted one of the more notable refusals when Beach, at her suggestion, wrote to George Bernard Shaw (Mabel Fitzgerald had been Shaw’s secretary at one time). Shaw replied explaining why he could not subscribe. According to Shaw Ulysses was a ‘revolting record of a disgusting phase of civilization, but it is a truthful one...to me it all hideously real’. But, as regards purchasing it, he was an elderly Irish gentleman and ‘if you imagine that any Irishman, much less an elderly one, would pay 150 francs for such a book, you know little of my countrymen.’ Joyce circulated this letter widely, seeing that the refusal was perhaps as useful for publicity as a subscription and, in any event, as he wrote to Weaver he had won a bet that Shaw would refuse: ‘Copies of the prospectus were sent to W.B Yeats, Mr George Moore and of course they did not reply. This will not prevent them from subscribing to the book anonymously through a bookseller in common with the elderly Irish gentleman’. Yeats did however subscribe more directly, Ezra Pound bringing his subscription form into Shakespeare and Company. Ernest Hemingway and Andre Gide were other early subscribers in the bookshop, while T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia), tenor John McCormack and American novelist, John Passos, were among the early postal ones.

The prospectus contained a recommendation from the French poet and novelist Valery Larbaud whom Beach had introduced to Joyce earlier that year. Having read the Little Review extracts Larbaud was enthusiastic about the work and, with Beach and Joyce, planned a special occasion or séance to publicise the publication which would include readings of passages in English and French. Even more significantly for the final phase of the novel, Larbaud offered his apartment to the Joyces for the summer so he could work in more comfort as the writing became more intense, both in finishing the final episodes and correcting the printed galleys.

Being part of the active social circle around Shakespeare and Company had other pitfalls for Joyce, who was now socialising with visiting luminaries such as Wyndham Lewis and new friends, like the American writer Robert McAlmon. As he wrote to Frank Budgen in Zurich: ‘Had several uproarious all night sittings (and dancings) with Lewis as he will perhaps tell you. I like him.’ McAlmon was a source of funds as well as amusement, regularly subsidising Joyce, but, according to Beach, he was a useful advocate for new subscriptions in Paris as well as helping in typing some of the late work on the book. McAlmon later chronicled some of their escapades. His outings with Joyce were usually weekly but the arrival of Lewis saw them out nightly, often to the Gypsy bar, where prostitutes and late night drinkers mingled in scenes similar to the Circe scenes Joyce was still sorting:

‘...Joyce, watching would be amused, but inevitably there came a time when drink so moved his spirit that he began quoting from his own work or reciting long passages of Dante in rolling sonorous Italian. I believed that Joyce might have been a priest upon hearing him recite Dante as though saying mass. Lewis sometimes came through with recitations of Verlaine, but he did not get the owl eyes and mesmerising expression on his face which was automatically Joyce’s. Amid the clink of glasses, jazz music badly played by a French orchestra, the chatter and laughter of the whores, Joyce went on reciting Dante’.

McAlmon left his account for his memoir, Being Geniuses Together.

Lewis was not as discreet and on meeting Harriet Weaver in London in June told her that Joyce entertained lavishly and was often inebriated at the end of the evening. This was a startling revelation to Weaver who had been brought up to believe that drink was one of the great evils and who had as a social worker seen the damage it did to the health of the individuals and the welfare of their families. She wrote to Joyce and as her biographers put it: ‘She told him what Mr Lewis had told her and went on to explain , almost apologetically, what she thought about drink – a great evil – and how much disturbed she was to learn that he allowed it to get the better of him.’ A panicked Joyce wrote to Budgen for advice. He advised him to play it all down. Joyce replied to Weaver in a long letter detailing all the false rumours that had been spread about him, in Dublin, Trieste, Zurich, Paris, and even in America. Remarking at one point that ‘this doesn’t seem to reply to your letter after all’, he went on: ‘You already have one proof of my intense stupidity. Here now is an example of my emptiness. I have not read a work of literature for several years. My head is full of pebbles and rubbish and broken matches and lots of glass picked up ‘most everywhere’. The task I set myself technically in writing a book from eighteen different points of view and in as many styles, all apparently unknown or undiscovered by my fellow tradesmen, that, and the nature of the legend chosen would be enough to upset anyone’s mental balance. I want to finish the book and try and settle my entangled material affairs definitely one way or the other.’ He finished: ‘I now end this long rambling shambling speech, having said nothing of the darker aspects of my detestable character. I suppose the law should take its course with me because it must now seem to you a waste of rope to accomplish the dissolution of a person who has now dissolved visibly and possesses scarcely as much ‘pendibility’ as an uninhabited dressing gown.’ Joyce did not let his defence rest there and got McAlmon to write to Weaver that Joyce drank ‘in moderation’ and held his drink properly ‘like a gentleman’. In conversation with McAlmon later, Weaver reconciled to the situation saying that if Mr Joyce was working and well that was what mattered most.

Arthur Power saw at first hand the impact Joyce’s lifestyle was having on his family when he called on him some time after their meeting with an invitation to a party that he felt Joyce would enjoy. The family were not welcoming: ‘Since Joyce’s eyes were very weak at the time, he was forbidden to drink, and they looked on me as the proverbial drunken Irishman inviting him out on a Celtic bash. Giorgio, his son, stood over my chair with his legs apart as much as to say, “When are you going to leave?” It was an awkward situation…Joyce bending to the storm with a rueful smile refused my invitation.’ Telling him as he left: ‘you know I am an intelligent man, but I have to put up with this sort of thing, however...we will meet again.’

Power was soon invited back to the flat and became friends with the family, being particularly impressed with Nora ‘who realised that I had no wish to lead her husband into drinking bouts, that I disliked drinking to excess.’ He saw how hard Joyce was working, knowing not to call until he was finishing his work in the late afternoon: ‘he used to come into the room from his study wearing that short white working-coat of his, not unlike a dentist’s, and collapse into the armchair with his usual long, heart-felt sigh. As often as not Mrs Joyce would say to him, ‘“For God’s sake Jim, take that coat off you.” But the only answer she got was his Gioconda smile, and he would gaze back humorously at me through his thick glasses.’

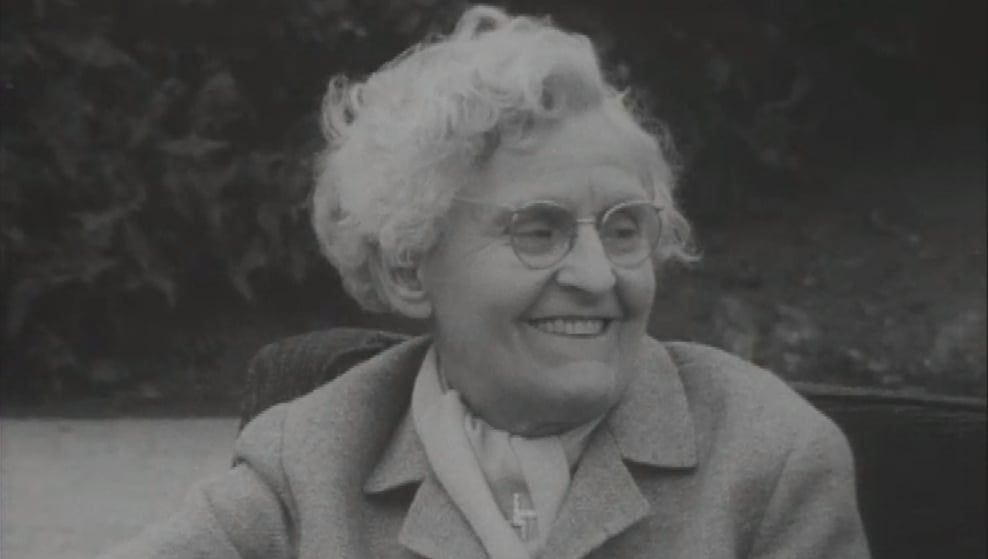

Arthur Power, photographed for RTÉ Television's Irish language current affairs programme, 'Féach', on 20 January 1974 (Image: RTÉ Archives)

The family’s concern for his health was very justified.

Joyce had an attack of iritis in May and then in early July got a more severe attack which caused him to refrain from working for a number of weeks. He had now to manage everything differently as he explained to Weaver: ‘I have been obliged to reduce my working hours from about sixteen hours daily to six in consequence of an attack I got, some kind of syncope it seemed to be. It came on me in a musichall where I had gone with my son feeling my head too light for work. With his help and that of an agent I was got into a taxi and brought into a night pharmacy where they gave me some ether, I think. The attack lasted about two hours and, being very nervous, I was much alarmed. Since then I have been training for a Marathon race by walking 12 or 14 kilometres every day and looking carefully into the Seine to see if there is any place I could throw Bloom in with a 50lb weight tied to his feet.’

His illness was such that he was not able to leave the apartment to have a meal with John Quinn who was in Paris, Quinn coming to see him instead. He had a further attack in early September when he wrote to Weaver about their proposal to amalgamate all of Joyce’s works by making payments to his previous publishers: ‘Incredible though it seems I have a new eye attack threatening me. I seem exhausted but am working as much as I dare… I hope that...nobody except you will write to me on that or any other subject. I am too nervous from illness and overwork to attend to business of any kind.’ Given the disruption and discomfort from these regular attacks it is even more remarkable to see the amount of detailed work Joyce completed in those months. Not just the composition and completion of his final two episodes but an extensive programme of work revising, emending and augmenting the original manuscript. It was not just a work of editing and emendation but a serious programme of creativity that transformed the work.

Joyce received the first proofs from the printer in the middle of June.

The Joyce family were then in the more comfortable surroundings of Larbaud in Rue du Cardinal Lemoine. As Joyce wrote to his Trieste friend, Francini Bruni: ‘It is unbelievable.’ Situated behind the Pantheon, ten minutes from the Luxembourg Gardens in a ‘kind of little park with access through two barred gates, absolute silence, great trees, birds…like being a hundred kilometres from Paris.’ As soon as the proofs arrived he began working on them as well as completing the final two episodes. As he explained to Budgen: ‘Ithaca is giving me fearful trouble. Corrected the first batch of proofs today up to Stephen on the strand…In the words of the Cyclops narrator the curse of my deaf and dumb arse light sideways on Bloom and all his blooms and blossoms.’

Following the tortuous work of completing Circe, Joyce

had expected to be able to finish the work quite quickly. The

return of Bloom to Eccles Street and Molly, of Ulysses to Ithaca

[and Penelope], had been planned from the time of his early work

on the novel. Before he left Trieste for Zurich in 1915 he had

already ‘sketched’ out some of the final episodes with

drafts and notes. He was then able to conclude Eumaeus,

the episode in the cabman’s shelter, quite quickly after

finishing the complete draft of Circe. (He began revising

Eumaeus in tandem with Circe after his books and notes

for these episodes arrived from Trieste in early November 1920.) A

draft was done by December 9th and the first section delivered to

the typist the first week in February 1921, with the remainder

finished by 18th February. Once typed Joyce could share copies

with his associates and both Ezra Pound in Paris and T.S. Eliot in

London were enthusiastic about the Circe and

Eumaeus drafts.

As he began work on the final two episodes, Joyce needed more of

the documents that he had left in Trieste and asked his friend

Ettore Schmitz (known as novelist Italo Svevo) to collect them

from his brother-in-law’s house if he was coming to Paris.

He told Schmitz that he would soon use up the notes he had brought

with him ‘so as to write these two episodes’ and that

there was in his brother’s bedroom in his

brother-in-law’s house an ‘oilskin briefcase fastened

with a rubber band having the colour of a nun’s belly and

with the approximate dimensions of 95 cm by 70 cm. In this

briefcase I have lodged the written symbols of the languid sparks

which flashed at times across my soul.…So, dear Signor

Schmitz, if there is someone in your family who is traveling this

way, he would do me a great favour by bringing me this bundle,

which is not at all heavy since, you understand, it is full of

papers which I have written carefully with a pen and at times with

a bleistift [a pencil] when I had no pen. But be careful not to

break the rubber band because the papers will fall into disorder.

The best thing would be to take a suitcase which can be locked

with a key so nobody can open it.’ Joyce on returning to

Trieste from Zurich in 1919 had organised his collection of notes

and drafts, episode by episode, to assist the completion of the

novel with the intention of augmenting the already published

episodes and linking them together in what was an evolving concept

for the work as a whole.

Ithaca, where Bloom returns to Eccles Street with Stephen, had been begun in earnest at the end of February 1921, building on the earlier sketches.

Joyce outlined the approach to Budgen: ‘I am writing Ithaca in the form of a mathematical catechism. All events are resolved into their cosmic physical, psychical etc equivalents, e.g. Bloom jumping down the area, drawing water from the tap, the micturation in the garden, the cone of incense, lighted candle and statue so that not only will the reader know everything and know it in the baldest coldest way, but Bloom and Stephen thereby become heavenly bodies, wanderers like the stars at which they gaze. The last word (human, all too human) is left to Penelope. This is the indispensable countersign to Bloom’s passport to eternity’. The notes for Ithaca and Penelope were brought by Schmitz during March. ‘By dint of writing several letters and telegrams to Trieste I received safely about a fortnight ago the bag full of notes for Ulysses. I regard this as one of the triumphs of my life.’

The earliest surviving manuscript of Ithaca is in the National Library of Ireland and is described by Luca Crispi as comprising both earlier material and newly composed segments not yet in the final sequence: ’It is a mixed document in which Joyce compiled an older collection of rudimentary, non-sequential question and answer text blocks, some of which he may have written as early as 1915-16. He also wrote a number of newer questions and answers in this manuscript, some of which were based in part on notes he regathered in notes repositiories that he compiled in Paris in 1921.’ The episode had grown in ambition from its earlier conception and now had another significant function in drawing together the themes of the book in the precise catechism, question and answer, style he intended.

He was recovering from the eye attacks, struggling with the complexities of Ithaca and the detailed revision of the earlier episodes as they came from the printers but he still managed to begin the final drafting of Penelope, the last episode, as he outlined to Weaver in August: ‘I write and revise and correct with one or two eyes about twelve hours a day I should say, stopping for intervals of five minutes or so when I can’t see any more. My brain reels after it but that is nothing compared with the reeling of my readers’ brains….I have the greater part of Ithaca but it has to be completed, revised and rearranged above all on account of its scheme. I have also written the first sentence of Penelope but as this contains about 2500 words the deed is more than it seems to be. The episode consists of eight or nine sentences equally sesquipedalian and ends with a monosyllable.’ A week later Joyce was more explicit to Budgen: ‘Penelope is the clou of the book…It begins and ends with the female word yes…Though probably more obscene than any preceding episode it seems to me to be perfectly sane full amoral fertilisable untrustworthy engaging shrewd limited prudent indifferent (sic)...’

Again it is the National Library of Ireland’s Joyce collection that contains the earliest extant manuscript of Penelope. Luca Crispi has dated this to earlier summer 1921 and describes it as an ‘intermediary draft’: ‘The clear disposition of the base text on this manscript indicates that Joyce was copying from an earlier, now missing proto-draft and/or draft of the episode, the more basic elements of which he presumably wrote more than once from 1914 to 1916. He then revised the penultimate early draft in Paris before the extant intermediary draft.’

As with Ithaca he used notes compiled in Paris (which are also in the NLI) to prepare this draft and there was at least one further draft before it was sent for typing. Michael Groden, who assessed these Joyce documents before purchase for the National Library of Ireland, saw here Joyce’s creativity at work: ‘The ‘Penelope’ draft even showed Joyce revising the novel’s very last words: he first wrote “and I said I would” and then crossed out “would” and substituted “will” before he added the concluding “yes”. This revision of one simple word merely changes the verb tense, but it turns Molly’s rather formulaic memory of her answer to Bloom’s marriage proposal – “I said I would yes” into the stunning self-quotation of “I said I will yes”. It says as much to me about Joyce’s genius as anything I know about how he wrote.’

The affirmative tone reflected in this change was indicative of the determined purpose with which Joyce worked during this final period. He knew that his novel was nearing publication and each week brought him closer. He was eager to have the work read and as more complete typescripts were now being prepared he was able to share sections, even full drafts with his friends and associates. The new friend of 1921, Arthur Power was one: ‘Joyce had lent me the manuscript of Ulysses, which I carried in a bulky parcel tied up in brown paper, across the taxi-ridden streets back to my studio in constant fear that I should be run over and the manuscript lost. But when I sat down to read it I found myself confused by its novelty and lost in the fantasia of its complicated prose, not knowing if a thing is really happening or was just a Celtic whorl. In fact I later irritated Joyce by enquiring into the details of Bloom’s encounter with Gerty MacDowell on the beach.

- “Nothing happened between them’ he replied. “It all took place in Bloom’s imagination.” ’

He told Power that while A Portrait of the Artist was a book of his youth, Ulysses was the book of his maturity:”Ulysses is more satisfying and better resolved, for youth is a time of torment in which you can see nothing clearly. But in Ulysses I have tried to see life clearly, I think and as a whole; for Ulysses was always my hero. Yes, even in my tormented youth, but it has taken me half a lifetime to reach the necessary equilibrium to express it, for my youth was exceptionally violent; painful and violent.’

Power was though clear of one thing: a ‘revolution’ had been launched. ‘Taking for his subject his native city, which once he had evidently hated, but which now he had re-found to cherish, Joyce had created a new realism, in an atmosphere that was at the same time half factual and half dream.’

Joyce’s progress on Penelope had now overtaken that of Ithaca and Joyce had enlisted the help of writer Robert McAlmon in preparing the typescripts. He sent them to the printer Darantiere in two segments, one on 22nd September and the second on 25th. It took another month of solid work before Ithaca was ready for the printer. Joyce described the work: ‘...am working like a lunatic, trying to revise and improve and connect and continue all at the one time.’ He wrote to Ezra Pound on October 29th : ‘You will be glad to hear with the conclusion of the Ithaca episode this evening (Penelope being already finished) the writing of Ulysses is ended.’ To McAlmon he gave a clearer picture: ‘A few lines to say that I have just finished the Ithaca episode so at last the writing of Ulysses is finished. I have still a lot of proofreading and revising to do but the composition is at end… O, Deo Gratias!”

In confirming the news to Harriet Weaver, Joyce remarked on the importance of dates: ‘A coincidence is that of birthdays in connection with my books. A Portrait of the Artist which first appeared serially in your paper on 2 February finished on 1 September. Ulysses began on I March (birthday of a friend of mine, a Cornish painter [Budgen]) and was finished on Mr Pound’s birthday, he tells me. I wonder on whose it will be published.’ This arrangement did though require a slight shifting of dates as Pound’s birthday was October 30th but it did not stop Pound claiming it later in The Little Review as an epochal date ending the Christian Era, and beginning ‘YEAR 1 p.s. U, (and as the Pound Era preceded the era Fascista)’.

Joyce’s comment to McAlmon that there was still work to be done on the proofs was an understatement.

Even in November he was still gathering material to be added in. He had written a number of times to his Aunt Josephine in Dublin with a series of detailed questions apologising for doing so at such a dangerous ‘time: ‘If the country had not been turned into a slaughterhouse of course I should have gone there and got what I wanted.’ On 2nd November he wrote again to ask: ‘Is it possible for an ordinary person to climb over the area railings of no 7 Eccles Street either from the path or the steps, lower himself from the lowest part of the railings till his feet are within 2 feet or 3 of the ground and drop unhurt. I saw it done myself but by a man of rather athletic build.’ He asked whether there was skating on the frozen canal in the cold February of 1893 and also any detail she had of Mat Dillon’s daughter Mamy who was in Spain. The first of these questions was for Ithaca which had gone to the printers, but which still had to undergo further expansion at the proof stage. The question about Mat Dillon’s daughter was for Penelope. It was at gatherings in Mat Dillon’s that the early romance of the Blooms blossomed and Joyce was also collecting detail on Molly’s Spanish connections. This was part of a careful process of character enhancement of both Blooms, as Luca Crispi has shown in his work on Becoming the Blooms. Crispi describes how Joyce adds detail at each stage to further deepen the main characters and their back story.

Joyce estimated to Sylvia Beach that nearly one third of the book was added at the proof stage.

More recent analysis by Hans Gabler for Eric Bulson’s Ulysses by Numbers book puts it closer to a ‘twenty per cent’ augmentation. Joyce had been gathering notes for all the episodes which he had put in order in Trieste before coming to Paris. He had, in Paris, used notebooks now in the National Library of Ireland to collate and order some of the material. The additions to the early episodes were not as substantial as those for the middle and late episodes (a pattern traced by Michael Groden in his Ulysses in Progress work, which paid particularly attention to the development of the Cyclops episode which was extensively augmented.) In her analysis of the development of the episodes that had been published in The Little Review, Clare Hutton outlined seven types of revision: making things more specific, deepening character through stream of consciousness, connecting the work by schematic and systematic additions, complicating the style of writing, embellishing micro-narratives and revising certain elements of speech to make them more Hibernian for certain characters. Joyce had prepared a schemata for the work and he wove elements through the episodes, connecting, complicating and sometimes just for some added humour.

He had gathered and ordered notes in a number of notebooks to assist the revision, sorting them by episode and sometimes even by character. In some cases these changes had a fundamental impact on how the episode looked (the headlines in Aeolus were introduced at this stage, the lists in Cyclops were greatly expanded and Joyce made the decisive removal of punctuation from Penelope).

WATCH: interview from 1962 with Sylvia Beach, the woman responsible for publishing James Joyce’s masterpiece, Ulysses. Click image to visit the RTÉ Archives website

This amount of revision had major implications for the printing.

It significantly changed the page count from the original projection of 592 to the eventual 732 (Beach had even to alter the prospectus by hand) with the cost doubling from the original estimate. There was also the challenge of getting the correct blue cover, reflecting the Greek flag, that Joyce wanted for the book. However, Darantiere proved to very adaptable, changing his printing practices and accepting corrections right down to the wire.

By December it was evident that, contrary to their original expectations, the book would not be published in 1921 and the target was now Joyce’s fortieth birthday.

The major event planned by Beach to coincide with the launch, the lecture and ‘séance’ prepared by Valery Larbaud, went ahead on December 7th. Joyce had given Larbaud a new version of his schema, extensive typescripts of the episodes including early proofs of Penelope for the evening. Translations of sections of Sirens and Penelope had been arranged by Adrienne Monnier from a young translator, Jacques Benoist-Méchin, and an American actor called Jimmy Light was to read original extracts. Beach had Joyce’s photo taken by Man Ray for the occasion. A crowd of over 250 people attended the evening in two rooms of Monnier’s La Maison des Amis des Livres. Beach and Monnier were delighted with the response to the lecture and the readings. Joyce had been called reluctantly from the back room to receive sustained applause from the crowd. Larbaud had dropped some more explicit passages to Joyce’s amusement rather than disapproval. He told Weaver: ‘I daresay what he read was bad enough in all conscience but there was no sign of any kind of protest and had he read the extra few lines the equilibrium of the solar system would not have been greatly disturbed.’

Joyce expressed to Weaver his fear that some last minute catastrophe might still happen to prevent publication but worked steadily on the last proofs right up to January 31st. Changes were still being made on the proofs as he and Beach approved them, sometimes by phone calls or telegrams. A statement by Beach was added reflecting the pressure they were all under to complete the task: ‘The publisher asks the reader’s indulgence for typographical errors unavoidable in the exceptional circumstances. S.B.’ Even after sending off the final revisions for Ithaca on 30th January Joyce had another thought and telegrammed the printer to change the word ‘atonement’ to ‘peace offering’.

Some of these very last changes to the text were significant.

In the final sections of Penelope, sent to the printer on January 31st, Joyce wrote an addition to Molly’s regret that Stephen had left and not stayed over either in the [empty] room that was upstairs or Milly’s bed in the back room: ’he could do his writing and studies at the table in there for all the scribbling he does at it and if he wants to read in bed in the morning like me as hes making the breakfast for 1 he can make it for 2.’ Given that it is one of Joyce’s last acts in the composition of the work, it is an interesting vignette of the writer and his characters. Then to complete the work on the last page Joyce punctuates with another “yes” in bold here: ‘…and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes my mountain flower and first I put my arms around him yes and drew him down to me so he could feel my breasts all perfume yes and his heart was going like mad and yes I said I will Yes.’

On 1st February Maurice Darantiere wrote to say that three copies of Ulysses would be sent by ‘Lettres Express’ to Beach’s address that evening.

Beach had impressed on Darantiere the importance of having at least one copy for Joyce on his birthday but he was fearful that the post would not arrive in time and got her to call the printer. As she recalled: ‘He made no promises but I knew Darantiere, and I was not surprised when I received a telegram from him on February 1st asking me to meet the express from Dijon at 7.a.m. the next day; the conductor would have two copies of Ulysses for me. I was on the platform, my heart going like a locomotive, as the train from Dijon came slowly to a standstill and I saw the conductor getting off, holding a parcel and looking around for someone - me. In a few minutes, I was ringing the doorbell at the Joyces and handing them Copy No. 1 of Ulysses. It was February 2, 1922. Copy No. 2 was for Shakespeare and Company, and I made the mistake of putting it on view in the window’.

On the day Joyce sent appreciative messages to Beach, Darantiere, Weaver, McAlmon and others who had helped him on the work and attended a celebratory dinner with Nora and friends that evening. (He would later further recognise these efforts of Darantiere in Finnegans Wake ‘thank Maurice, lastly when all is zed and done, the penelopean patience of its last paraphe, a colophon of no fewer than seven hundred and thirty two strokes tailed by a leaping lasso –‘). Joyce reportedly kept his copy of the book safely in a package under his seat until after the meal when he untied the parcel and laid it in its blue covers on the table for all to see. The copies of the book that Joyce and Beach had received were not from the deluxe edition so not in fact those numbered 1 and 2. As he explained to Weaver: ‘Two copies of Ulysses (nos. 900 and 901) reached Paris on 2 February and two further copies (nos. 251 and 252) on 5 February. One copy is on show, the other three were taken by subscribers who were leaving for different parts of the world…The first 10 copies of the edition de luxe will not be ready before Saturday so that you will not receive your copy (No.1) before Tuesday of next week at the earliest.’

Just over a week after publication, Joyce met one of his Dublin subscribers, Desmond Fitzgerald, father of the future Taoiseach: ‘The Dáil Éireann minister for propaganda called on me and wished to know if I intended to return to Ireland – to which I returned an evasive answer. He is proposing me, it seems for the Nobel prize in his capacity of cabinet minister as soon as the Treaty is ratified at Westminister though not in the name of his cabinet. I will take on a small bet that if he does not change his mind when he sees the complete text he will lose his portfolio while I have not the faintest chance of being awarded the prize.’ In this last prediction he was correct. He was never to win the prize. Fitzgerald, who became Minister of External Affairs, in the Irish Free State government, would propose the nomination of W.B Yeats to the Senate later that year. Yeats would win the Nobel Prize in 1923.

The deluxe copy no. 1 signed and dedicated to Harriet Shaw Weaver was given by Weaver to the National Library of Ireland and is now on display in the new Museum of Literature Ireland. Sylvia Beach was given number 2, and Margaret Anderson, who had first published Ulysses in The Little Review, number 3.

Joyce chose copy 1,000 for Nora and Arthur Power was present as he inscribed it to his wife. Power told Richard Ellmann that Nora at once offered to sell it to him: ‘Joyce smiled, but was not pleased.’ (Nora retained her copy and it is with Beach’s in the University of Buffalo). Ellmann links Nora’s offer with examples of Joyce’s frustration at her reported refusal to read the book. Power saw it differently as the taunt of a ‘strong confident woman cutting her man down to size.’ As Sylvia Beach put it, ‘I could see for myself that it was quite unnecessary for Nora to read Ulysses, was she not the source of his inspiration?’

But perhaps a more significant answer is found when you trace the time from the day on which Ulysses is set 16th June 1904 to the day it was published, 2nd February 1922, underscored by the final note in the book ‘Trieste-Zurich-Paris, 1914-1921.’ Nora Joyce had no need to read Ulysses, she had lived it.

Ed Mulhall is a former Managing Director of RTÉ News and Current Affairs and an Editorial Advisor to Century Ireland