Explainer: Why did the United States join World War One?

War in Europe began in the late summer of 1914 and from the outset the United States clung to a policy of strict neutrality. Despite the loss of American life as a result of the War on the Atlantic Ocean (such as the sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915), President Wilson constantly argued that the United States should remain out of the conflict. However, on 6 April 1917 the United States Congress declared war on Germany. By June 1917 the first American troops, 14,000 men of the American Expeditionary Force, arrived in France. By the end of the War in 1918 a million American troops were in Europe. So why and how did the United States go from a policy of neutrality to a fully blown engagement with the war in Europe?

Q: Why did the United States choose to stay neutral in

1914?

When war broke out in Europe in 1914 President Wilson declared

that the United States would follow a strict policy of neutrality.

This was a product of a longstanding idea at the heart of American

foreign policy that the United States would not entangle itself

with alliances with other nations. Put simply the United States

did not concern itself with events and alliances in Europe and

thus stayed out of the war. Wilson was firmly opposed to war, and

believed that the key aim was to ensure peace, not only for the

United States but across the world. To that end he sent a leading

aide, Colonel House, to Europe in the autumn of 1914 in an attempt

to broker a peace deal.

Q: Why didn’t German attacks on American shipping force

Wilson to act?

If the war had been solely fought on land it was likely that the

United States could have avoided the entanglement it feared.

However, a key part of the war was the battle on the Atlantic.

Here, shipping lanes were patrolled and attacked by German U-Boats

in an attempt to cut supply lines to Britain. Following its policy

of neutrality the United States initially attempted to trade with

both Britain and its allies as well as with Germany. However, in

practice the United States was only able to trade with Britain and

its allies, and all the goods sold (the value of which amounted to

$1.2 billion by 1916) had to be transported by ship across the

Atlantic. The German habit of attacking shipping meant that

American registered ships were sunk, and United States citizens

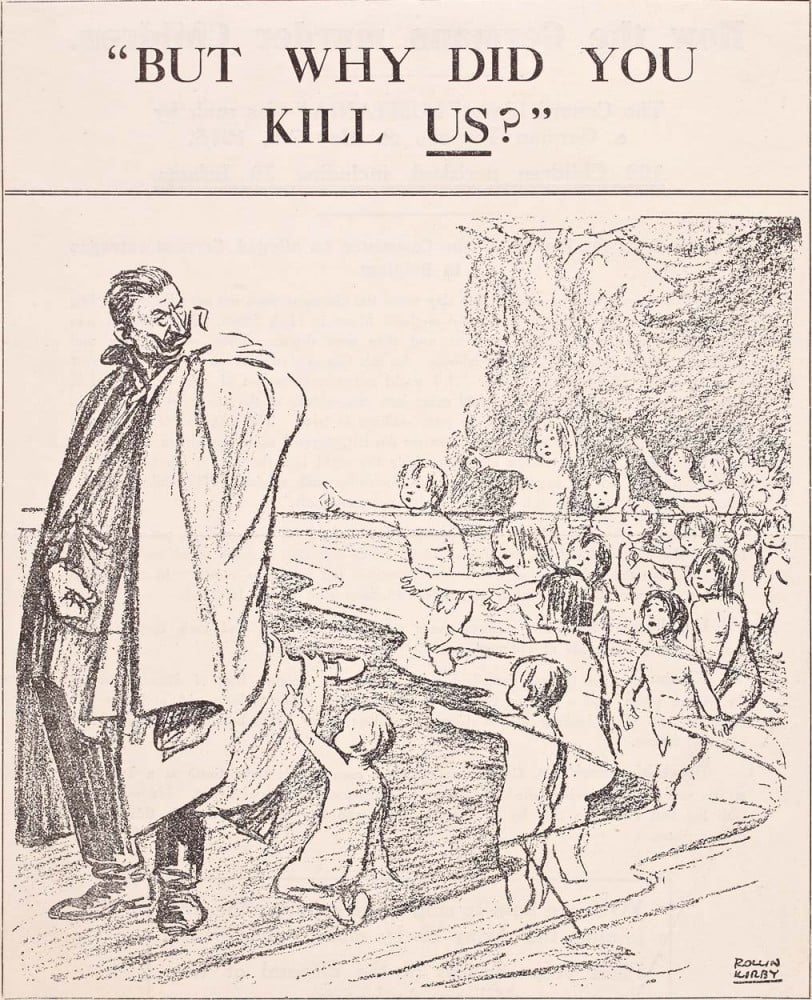

were killed (128 died when the Lusitania was sunk).

Wilson came under pressure to act after the sinking of the

Lusitania

and after protests from him, the Germans agreed to refrain from

attacking passenger vessels. By January 1917 however, German

military commanders argued that only an unrestricted blockade of

the Atlantic would achieve victory and once more targeted all

shipping. The decision undoubtedly edged the United States closer

to war in 1917.

|

|

L: An illustration from the New York Herald of the moment the torpedo hit the Lusitania in 1915 (Image: Library of Congress). Right: Anti-German propagana showing the ghosts of the children killed when the Lusitania went down haunting the Kaiser (Image: National Library of Ireland)

Q: What was the Zimmerman Telegram?

By the start of 1917 Germany was looking for additional allies. On

16 January 1917, the German Foreign Minister, Arthur Zimmerman,

sent a telegram to Mexico. In return for Mexico starting a war

against the United States, Germany promised to pay all associated

costs. The inflammatory telegram was intercepted by the British

who, in turn, passed it to Washington. The telegram was released

to the press on 28 February and published. How genuine

Zimmerman’s offer to Mexico was is hard to say, but the

telegram had a pronounced effect on turning American public

opinion against Germany.

Q: Why did Wilson decide to push for a declaration of

War?

The combined effect of the Zimmerman telegram and renewed attacks

on American shipping are seen by historians as the immediate

catalysts for pushing the United States to war. In addition there

is also a sense that the initial public support for neutrality had

wavered in the years since 1914. This combined with the massive

financial investment (both trade and loans) that the United States

had made in the allied nations meant that, no matter how it was

presented, there was a degree of self-interest in the the decision

to go to war. When President Wilson spoke to Congress on 2 April,

asking that they vote for a declaration of war, he argued that the

United States had no selfish interests in joining the conflict but

that American participation would make the world safer for

democracy. On 6 April the declaration of war was passed by

Congress.

President Woodrow Wilson (Image: Le Petit Journal)

Q: Was there opposition to the United States joining the

War?

By the spring of 1917 American public opinion appeared to have

supported the move towards a declaration of war. There were many

groups that opposed the war such as the small socialist party,

various church groups, sections of the women’s movement and

large swathes of the German-American population. The most

vociferous opposition to the war came from the Irish-American

population. They stressed a continuation of neutrality not because

they supported Germany in any way, but rather they opposed British

policy towards Ireland.

Q: What was the outcome of the decision to join the

War?

After the first American troops landed in Europe in June 1917 the

involvement of the United States escalated rapidly. By the end of

the war in November 1918 10,000 American troops were arriving in

France every day. Questions have been asked by historians as to

how effective the United States forces were on the battle field,

but acknowledge that the simple replenishment of the numbers of

allied forces at the front had a significant impact. At the close

of the war 53,402 Americans had been killed in combat and over

200,000 had been wounded. The entry of the United States meant

that President Wilson was able to play a key role in the peace

talks at Versailles that would redraw the map of Europe, and it is

clear that wartime manufacturing greatly benefitted the American

economy.

Prof. Mike Cronin is Academic Director at Boston College-Ireland and a Director of Century Ireland