‘Other cheated dead’: Murder and reprisals in Galway’s Gregory-Yeats Country

By Ray Burke

William Butler Yeats disagreed with his close friend and collaborator Lady Augusta Gregory about a 24-line poem that he wrote one hundred years ago, in November 1920, at the height of the War of Independence.

He thought that the poem was ‘good’, but Lady Gregory begged him to suppress it and it was not published until 1948, when both of them had been dead for some years.

Lady Gregory said the poem gave her ‘extraordinary pain’. It was addressed to the ghost of her only son, Major Robert Gregory, who had been killed nearly three years previously when his aircraft crashed on the Italian front during World War One. It was the last of four elegies to Robert Gregory that Yeats wrote at Lady Gregory’s request, but when she first read it she complained: ‘I cannot bear the dragging of R from his grave to make what I think not a very sincere poem’.

Yeats argued that he hoped her objection was on ‘public, or local grounds, and not on any personal dislike to it’. He said he thought the poem ‘might touch some one individual mind of a man in power’, but she was annoyed that he was writing from the safety and comfort of Oxfordshire while she was surrounded by terror, with death having come almost to her own doorstep at Coole Park, near Gort, Co. Galway.

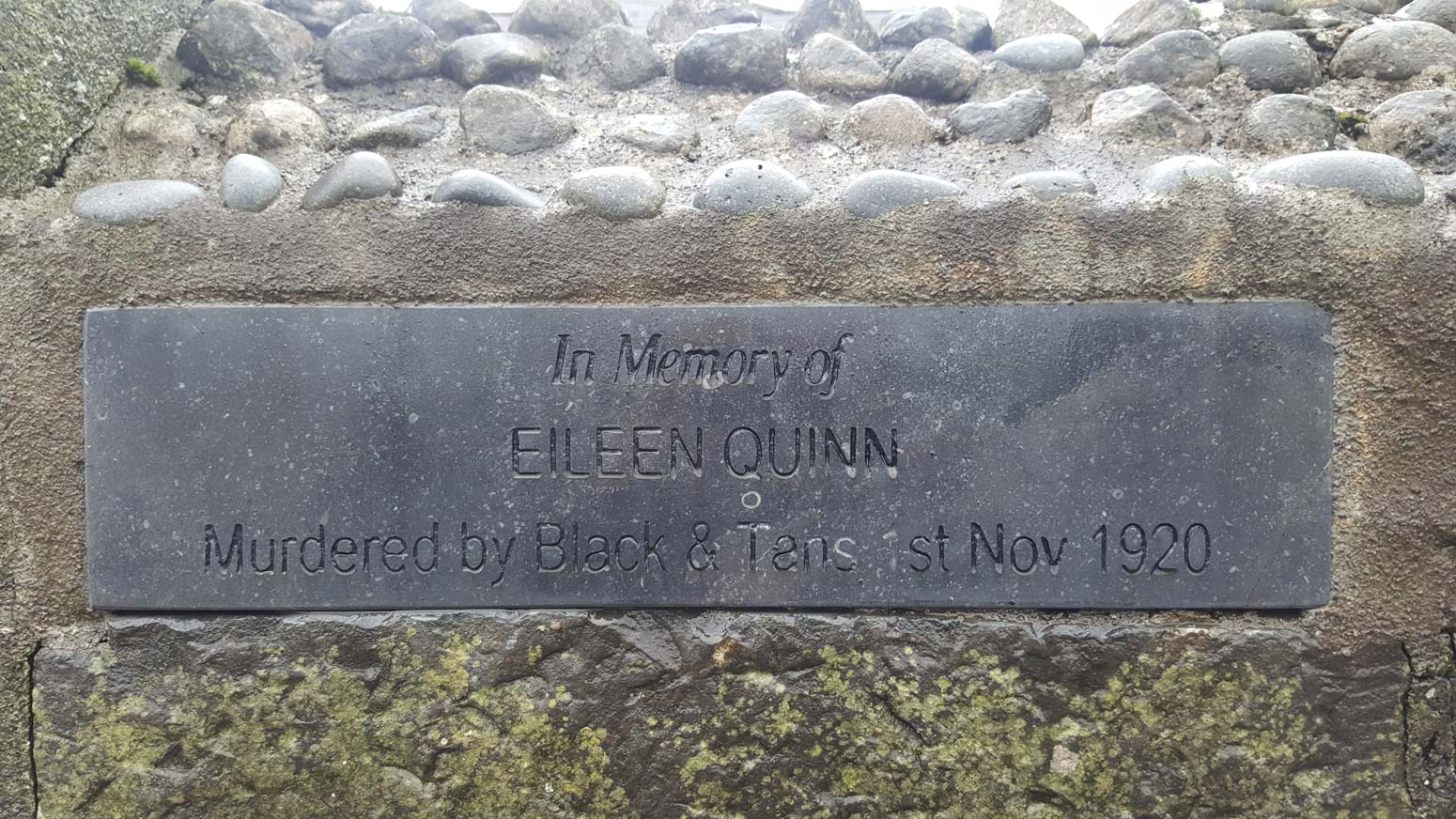

The poem’s second ‘ghost’, after Robert Gregory, was the young wife of one of Lady Gregory’s tenants and closest neighbours, who was shot dead outside her home on 1 November 1920. Eileen Quinn, aged 24 years, was the mother of three children and heavily pregnant with a fourth when she was shot by passing Auxiliaries while sitting on the low wall outside her family home with one of her children in her arms. Her husband, Malachi, was renting and hoping to buy more land from Lady Gregory around his family home at Corker, the townland immediately north of Coole Demense and Kiltartan.

‘Where may new-married women sit/and suckle children now?’ Yeats asked in the contentious poem. ‘Armed men/May murder them in passing by/Nor law not parliament take heed’. Addressing the ghost of Robert Gregory directly, Yeats wrote that ‘Half-drunk or whole-mad soldiery /Are murdering your tenants there’ before linking him and Eileen Quinn ‘among the other cheated dead’.

Eileen Quinn was awaiting Malachi’s return from a fair in Gort when she was shot. He found her dying on the kitchen settee, at the end of a trail of blood that led from the front wall through the path and porch. She lingered for several hours with blood oozing through her clothes. One of the doctors who attended her, Dr Sandys from Gort, said ‘she had bled so much that she could bleed no more.’

Eileen Quinn's house. (Image: Courtesy of Orla Higgins)

‘From 3 pm to 10.30 pm she lingered on in pain’, the Gort catholic curate, Fr John Considine, told the Connacht Tribune. ‘Occasionally she would clasp my hand, pull me towards her and say: ‘I am done, I am done’.’ He said she told him when he arrived that she had been shot ‘by police’. He said that he immediately sent word to the Gort RIC head constable, who arrived but refused to take a statement from the dying woman. Local lore records that some neighbouring women, knowing that she would not survive, tried in vain that evening to remove the foetus from her womb as she lay dying.

*****

The verdict of the military court of inquiry was that ‘death was due to shock and haemorrhage by a bullet wound in the groin fired by some occupant of a police car proceeding along the Gort-Ardrahan road on the 1 November 1920.’ The inquiry members said they were ‘of the opinion that the shot was one of the shots fired as a precautionary measure, and in view of the facts record a verdict of ‘death by misadventure.’

This verdict was alluded to in another major, and backdated, Yeats poem, Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen, published in 1921 and included in the 1928 collection The Tower. In the fourth stanza of Nineteen Hundred and Nineteen he wrote:

A drunken soldiery

Can leave the mother, murdered at her door,

To crawl in her own blood and go scot-free

Lady Gregory wrote at length about Eileen Quinn’s death in the Fleet Street weekly, the Nation, and in her diaries. Her 13 November Nation article said:

3 November – A letter says: ‘A young woman was shot at in Kiltartan yesterday from a lorry of passing military; it sounds dreadful...it was MQ’s young wife who had been shot dead with her child in her arms.

5 November – J, who had been two nights at the wake-house, says the little children said: ‘Mamma’s asleep’, ‘You could take up the three little children together in your arms.’ And there was another coming. G, living on that road, has been complaining – they have been firing constantly as they pass; his sick daughter cannot sleep. The letter adds:

‘Monday was a Holy Day, All Saints Day. M [Malachi] had gone to Gort.They were so happy they had just got in the harvest and had dug the potatoes and threshed the corn and were ready for the winter. She was out at the gate watching for him to come back. The lorries passed and shots were fired; the maid ran out and found her lying there. ‘Oh, I’m shot!’, she said. The whole place was splashed with blood like a butcher’s shop. D that went to the doctor had pellets put in him. They fired at D’s house as they passed and killed some fowl and they broke a window firing at C’s house. She lived a few hours in terrible pain. She said to the priest she had been shot by the police. It is strange that she had said a few days before to her husband that she dreamed she was shot by Black and Tans.’

‘My God! It is too cruel!’ her young husband writes.

The lorries had come from Galway, and going back from Gort, had fired even in the street ‘so that the houses shook’. ‘An ambush!’ How could they be afraid of an ambush? Not a wood or any shelter near. A big open country like that!’

The 13 November article, headlined ‘Murder by the

Throat’ after Prime Minister Lloyd George’s remark

about the war in Ireland, was one of a weekly series that Lady

Gregory wrote anonymously in the Nation between October

1920 and January 1921. They were usually by-lined ‘a

well-known Irish landlord’ or ‘a distinguished writer

and landlord’. The first article was introduced as being

‘from a quiet part of Ireland, not dominated by the

extremists.’

In her 18 December article, she wrote:

‘These Black and Tans can do what they like, and no check on them. Look how the Head Constable was afraid to take a deposition from Mrs Quinn before she died, and he in the house.’

Her final piece in January 1921 quotes a neighbour:

‘I saw the lorries leaving the town the day Mrs Quinn was shot; the men in them were firing, and two of them were lying back lifeless, as if drunk. Eight men of the old police go to keep guard of Father X’s house that is threatened by them because he gave evidence at that inquest’.

The Nation articles draw heavily on Lady Gregory’s diaries, later published, in edited form, as her journals. In these she referred repeatedly to Malachi Quinn’s distress after his wife’s death and to her own dealings with him. Her 9 November journal entry includes:

‘Malachi Quinn came to see me looking dreadfully worn and changed and his nerves broken, he could hardly speak when he came in. There had been aeroplanes flying very low over the place all day and as he came from Raheen one had swooped and fired three shots over him. He believes they shot her on purpose – they came so close. He was so fond of his wife ‘she could play every musical instrument.’ It is true the messenger sent for a Doctor was shot from another lorry, wounded in the leg.’

She regularly referred to him as ‘poor Malachi Quinn’ in her journals, but relations between them became strained when he fought fiercely over how much land he could purchase from the estate – legally owned by Lady Gregory’s daughter-in-law Margaret Gregory since Richard’s death – and at what price. Her journal entry for 24 April 1922, records a fraught meeting with Malachi from which she walked away and wrote: ‘A troublesome business, I think he is half crazed, and no wonder’.

Her entry for 30 April, as published, includes: ‘I awoke early and thought how sad it is with all this violence that we cannot have peace even within the demense, and I have been writing a letter to Malachi’. She added later: ‘I sent my letter to Malachi but without much hope.’

This letter, which she withheld from the journals, began: ‘Dear Malachi, I have been thinking of you this Sunday morning, and how sad it is that you are putting yourself among the lawbreakers.’ It concludes: ‘I cannot forget that terrible tragedy that broke your home happiness and I would be ready to say a good word either to Mrs Gregory or whatever land court may be set up. Indeed I have not told Mrs Gregory of what has taken place as I do not wish to set her against you (though if you spoke to her as you did to me the other day she may not have the same patience).’

Before the rows over land, Lady Gregory successfully lobbied the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Sir Hamar Greenwood, his wife, Lady Margo, and the Under Secretary, James MacMahon for ‘compensation (!)’ – her word and exclamation mark – for Malachi Quinn. ‘Another reason against the poem’, she wrote, referring to the poem she asked Yeats to suppress. Malachi Quinn was eventually given ‘a grant’ of £300.00, which he and Lady Gregory considered entirely inadequate.

Sir Hamar Greenwood, as Chief Secretary for Ireland, faced detailed questions in the House of Commons about violent deaths in County Galway every week during November 1920. He knew about Eileen Quinn’s killing not only through Lady Gregory’s lobbying but also because he had received a telegram about it from Fr Considine in Gort.

Asked by the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Joseph Devlin MP, about the killing, Greenwood replied:

‘I regret to have to say that Mrs Quinn was fatally wounded on the 1st instant. A court of inquiry opened on the case to-day at 10am. I am informed by the police authorities that two police lorries were passing at the time, and it may be that the wounding resulted from a shot fired in anticipation of an ambush in the neighbourhood.’

Pressed by Devlin and other MPs, he said that ‘in counties like Galway as it is today, the police and military have every right to anticipate ambushes, and to prevent them if possible’ and he protested against the allegation that they were ‘taking pot shots at innocent women.’

Devlin, MP for Fermanagh and Tyrone, raised the killing again in the adjournment debate that night. He said that if the killing was not deliberate it was the result of indiscriminate shooting, adding:

‘If the result is that this young mother, in the bloom and freshness of her womanhood, with her little child in her arms, and about to be the mother of another, is shot dead, let it ring forth throughout the world that this is Britain, the Britain that stood against the atrocities of the Turks in Armenia, that wept tears over crushed and oppressed humanity in every land under the sun, yet there is not one word of apology from the lips of the right hon. gentleman, or of sympathy for this poor woman, and for the desolate heart which is made motherless by these accursed crimes.’

Closing the debate, Greenwood also said:

‘In the disturbed condition of certain parts of Ireland today, there are bound to be stray shots; and the shot of a service rifle will carry nearly 3,000 yards from the point of discharge... One of the most effective ways, if not the only effective way, of defeating an ambush, is to fire in advance along the line of hedge or fence where the ambush is most likely to be.’

Asked if there was any proof that there was an ambush there, he replied:

‘The whole matter is under inquiry. No one regrets more than the police and the soldiers themselves if innocent persons are killed while they are carrying out their difficult and dangerous duties, and, I repeat, the responsibility is on those who continue the assassination and attempted assassination.’

Two weeks later, in a lengthy exchange about the killing with Lieutenant Commander Joseph Kenworthy, a Liberal MP for Hull Central, on 17 November, Greenwood said:

‘A military court of inquiry into this very sad and regrettable occurrence was held on the 4th instant, and gave the following verdict. The court having considered the evidence, and the medical evidence, are of opinion that Mrs Eileen Quinn, of Corker, Gort, in the County of Galway, met her death, due to shock and haemorrhage, caused by a bullet wound in the groin fired by some occupant of a police car proceeding along the Gort and Ardrahan road on The 1st November, 1920. They are of opinion that the shot was one of the shots fired as a precautionary measure, and, in view of the facts, record a verdict ‘Death by Misadventure.’ Mrs Quinn had a baby in her arms when struck by the bullet.’

The exchange continued:

Kenworthy:

‘May I ask the right hon. gentleman, firstly, whether he is aware that the country round the scene of this death was quite open, and, secondly, whether he knows that Mrs Quinn was sitting on the wall bounding the road, and in full view of the road, at 3 o'clock in the afternoon?’Greenwood:

‘I believe that Mrs Quinn was so seated, but I cannot consider that any road in a disturbed area – and this was a disturbed area – is a road on which the troops or the police are not justified in taking every precaution for their own safety.’Kenworthy:

‘May I ask if the right hon. entleman has satisfied himself that this sad case has been sifted to the bottom.’Greenwood:

‘Yes.’Kenworthy:

‘And is he aware that the county inspector of police – the head constable of Gort – refused to take the depositions of Mrs Quinn before she died, and was not called as a witness before the court?’Greenwood:

‘I have no knowledge of that myself. That may or may not be true, but I should be surprised if any head constable refused to do what he was told by his superior officer.’Kenworthy:

‘He was the superior officer.’Greenwood:

‘If some person outside the police force or the soldiers wanted him to do this or that, he is not compelled or expected to do it.’Kenworthy:

‘Is the right hon. gentleman not aware that the head constable was called in when the incident occurred but refused to take the deposition of the dying woman?’

Greenwood’s response is not recorded on the Commons transcript of that sitting, but he was asked the same question on the next day by Joseph McVeigh and by a Scottish Liberal MP, Sir Murdoch Mackenzie Wood. He said he had been told by the head constable that he had twice visited Mrs Quinn’s house and that on the first occasion she was being attended by a doctor and on the second occasion she was unconscious.

Asked if he was aware that the head constable had twice been asked by the local priest, Fr Considine, to take a statement from the dying woman, Greenwood replied that ‘none of the constables take their orders from priests.’ He also said he saw no reason to institute a new inquiry into the killing. He said that no military witnesses had been called to the military inquiry ‘as the military were in no way concerned in the matter.’

Greenwood later told the House of Commons that every single Auxiliary in Ireland was an ex-army officer ‘and most of them having decorations for valour’ and that disclosing the names of officers attending military courts may result in their assassination.

A week later he again refused to countenance re-opening the

inquiry into the killing and he described an allegation that Crown

forces were making war on women and children in Ireland as

‘monstrous’.

The Prime Minister, Lloyd George, also appeared to be familiar

with the circumstances of Eileen Quinn’s killing. In the

House of Commons seven days after she was killed, he denied that

alleged reprisals by police or military had official sanction and

he replied to a question about women being shot: ‘That was a

most unfortunate accident and no one, no decent person, would

suggest that it was deliberate.’ He added: ‘That is

one of the unfortunate incidents that always happen in war...It is

war on their side. It is a rebellion. It happens in every conflict

of that kind that innocent people, certainly without any intention

on the part of anyone, are hit.’

*****

Eileen Quinn was shot in what her family believed was a reprisal for the killing of an RIC Constable, Timothy Horan, two days previously in an IRA ambush at Castledaly, about five miles north east of Corker on the road between Gort and Loughrea. He died in the grounds of Castledaly catholic church when between 40 and 45 IRA men attacked a patrol of five RIC officers. A Kerryman, aged 40, he too was married with three young children.

The witness statement of IRA’s Gort company leader, Joseph Stanford, dictated decades later, said that Horan ‘was knocked off his bicycle and staggered to the church side of the road and got over the low wall of the church grounds. He was unable to go any farther, as fire was continuous on him, and he died there.’ Stanford said that the other policemen who got off their bicycles and dropped their rifles on the road fled via the Roxborough Demense (Lady Gregory’s childhood home and still owned at that time by one of her nephews) while the ambushers opened fire but failed to hit any of them. He did not say what had changed since early spring when the IRA had ordered its companies to disarm RIC men ‘while not harming them’ – a policy that he said had resulted in policemen being disarmed ‘without loss of life in Ballinderreen, Ardrahan, Peterswell, Beagh’.

The tortured remains of Harry and Pat Loughnane (Image: Bureau of Military History)

One of the IRA men who took part in the ambush in which Constable Timothy Horan died, Patrick Loughnane, was abducted by Auxiliaries at gunpoint from his home on the family farm at Shanaglish, Beagh, four miles (2.5k) south of Gort, just over three weeks later on 26 November. His brother Harry, a schoolteacher who was home on sick leave, was taken with him, despite their mother’s pleas that he was unwell. 10 days later their mutilated, grossly deformed and badly-charred bodies were found in a shallow grave after they had initially been dumped elsewhere.

Lady Gregory wrote about the killings in her journals and in the Nation, where on 18 December she further compromised her already-thin anonymity by referring to ‘the two Shanaglish boys who were taken away last Friday week and have not been heard of’. The article continued:

7 December: ...the sister went to see the bodies after they were found. She could not recognise one of them, but when she saw the other she cried out that it was her youngest brother...Boy went to bring them in – ‘when he took a hold of the hand of one of them it came off in his hand.’ Another said: ‘It will never be known the way they died. There is no one dare ask a question. But the work that is being done will never be forgotten in Ireland.’

9 December: ‘K says ‘mother could not recognise her sons. The Independent gives Mr Denis Henry’s ‘printed reply’ in Parliament to a question by Mr Devlin about these brothers: ‘he was informed they escaped from custody and had since not been heard of.’

10 December: ‘Funeral. The two priests who were present were in tears. Fr H asked the officers again and again to look upon the remains and say if such a thing could happen in a Christian country in the 20th Century?’

In her final article on 1 January 1921, she wrote:‘We are haunted by them, killing and burning and robbing, whipping you off in the dead of night. Look at what they did to those Loughnane boys. And they burned Z’s barn after, because it was there they were waked – burned it to the ground...Worse work they are doing than ever was done by Cromwell.’

Her journals also record that the man who initially found the bodies spent three days in bed suffering from shock; that the bodies looked as if they had been dragged behind lorries and that the boys’ mother and sister had been assured by police in Gort and Galway that they were safe in prison.

Lady Gregory placed a lengthy Connacht Tribune cutting on the civil action for damages taken by their mother a year later, and her own handwritten précis of the article, among the papers that were later lodged in the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library.

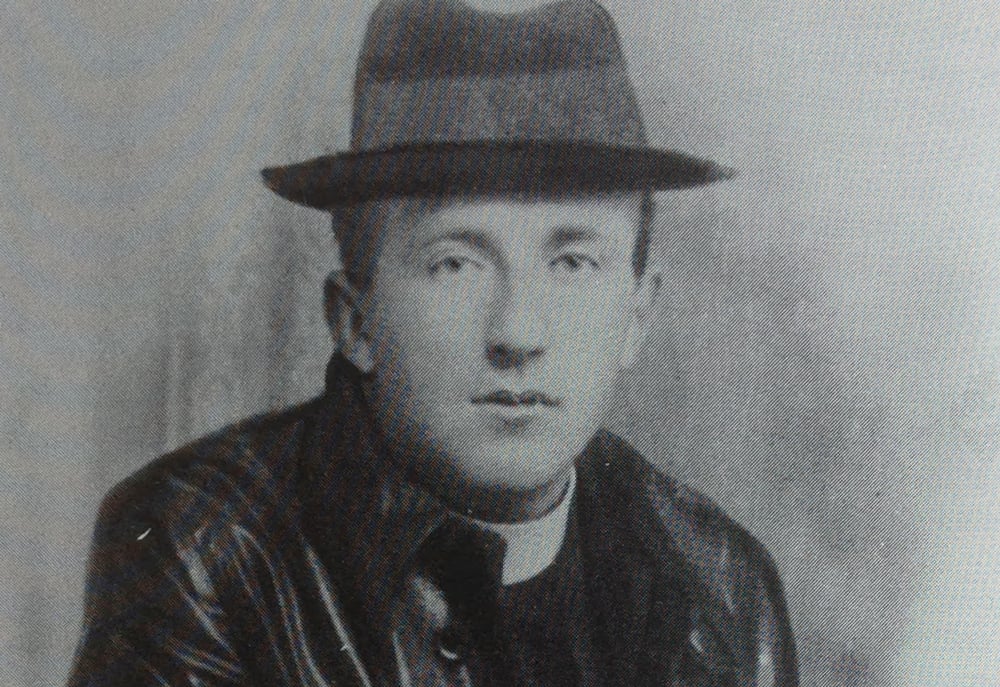

Seven days before the abduction of the Loughnane brothers, Sir Hamar Greenwood was asked in the House of Commons about the disappearance of a prominent catholic priest from Galway city, some 20 miles from Gort. Father Michael Griffin, a curate in Rahoon parish, was a Sinn Féin sympathiser who had been called to give the last rites to an Urban Councillor, Michael Walsh, who was shot dead and dumped into the sea at Long Walk in the city in late October. Fr Griffin was awakened at around midnight on Sunday 14 November and taken from his house by three armed men. His body was found six days later, partially- buried and face downward, in a field near Barna, a few miles west of the city. He had been shot in the right temple.

Fr Griffin’s home, No. 2 Montpelier Terrace, was one of a number of buildings on which Crown forces has posted notices threatening reprisals following the kidnapping in Barna, west of the city, of a schoolteacher, Patrick Joyce, who the IRA believed to be an RIC informer, in mid-October. Sir Hamar Greenwood linked the disappearances of the two men in a House of Commons reply on 19 November when both of them were still missing.

Asked to comment on a claim by the catholic bishop and all senior clergy in Galway that Crown forces were responsible for the disappearance of Fr Griffin, Greenwood read the text of a telegram he had received from the Galway RIC District Inspector. It said: ‘Rev. F. Griffin was an extreme Sinn Feiner and he and Mr P. W. Joyce, national school teacher, kidnapped on the 15th ultimo, were protagonists, and it was feared that Joyce had a number of friends who are determined to avenge his taking.’

The telegram went on: ‘Again, the Reverend Father Griffin appears to have delivered strong language in Barna Chapel on 14th instant, when he told his congregation that some among them were as bad as the ‘Black and Tans’... Inquiries are proceeding. There are no clues so far.’

Greenwood said he had no more information on the subject, but added: ‘I do not believe for a moment that this priest was kidnapped by any of the forces of the Crown ...The forces of the Crown in that area are doing their best to find the whereabouts of Father Griffin. I regret things of this kind more than anybody, and I should like this matter cleared up as soon as possible.’

In further exchanges in the House of Commons on the following Monday Greenwood reported that Fr Griffin’s body had been found. He said ‘all possible steps’ were being taken to investigate the killing and he protested that there was no evidence for the allegation ‘that this unfortunate priest had been done to death by any of the forces of the Crown.’

Two Irish MPs, Joseph Devlin and Joseph MacVeigh, and the MP for Kingston upon Hull Central Lieut. Commander Kenworthy, objected to the speaker that Winston Churchill had heckled from the government benches the words ‘Say Sinn Féiners’ when Greenwood was asked who was responsible for the priest’s death. Greenwood denied that he had claimed that the killing was committed ‘by Fr Griffin’s own parishioners’ and he added: ‘May I say, further, that the police officer in charge of the whole of this area, one of the most distinguished police officers, is himself a devout Roman Catholic, and the last man to tolerate any crime against a priest?’.

The Catholic Bishop of Galway, Thomas O’Dea, wrote to Greenwood three days later to say that Fr Griffin’s murder was the culmination of ‘exceptional ill-usage from Government forces’ in the Galway dioceses. He said that he himself had received a letter with a Galway postmark threatening that he would ‘meet with Fr Griffin’s fate’ if any Crown forces were interfered with in Galway.

Fr Michael Griffin. (Image: Courtesy of Orla Higgins)

Bishop O’Dea said that a similar threatening letter had been delivered to one of his priests, Fr John Considine, in Gort. He added: ‘Fr Considine’s only offence is that he has published what he believed to be the truth about the murder of Mrs Quinn, one of his parishioners, a young pregnant woman with a baby in her arms. To my knowledge he has done all in his power as a priest to preach and press the law of God against all crime and particularly against the murders of policemen, yet he is accused of stirring up the ‘blood and lust’ against the Crown forces, and consequently I hold you responsible for the life of this priest.’

Greenwood confirmed in the House of Commons on 29 November that he was aware of the threats against the bishop and priests in Galway and added that the police would give him every protection while investigating crimes in the diocese.

The Barna schoolteacher, Patrick Joyce, a 52-year-old father of four children, had been abducted from his family home and killed by the IRA in mid-October after they had intercepted in the Galway GPO five letters he had sent to Crown forces in Galway and to Sir Hamar Greenwood at the House of Commons, London. (Lady Gregory recorded in her Journals that when Winston Churchill was asked by a friend how Greenwood was appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, he replied: ‘No decent man would take the job.’)

*****

Barely six months after the Griffin and Joyce deaths near Galway city and the Horan, Quinn and Loughnane deaths near Gort, and less than two months before the truce was agreed, Lady Gregory’s daughter-in-law, Margaret Gregory, Robert’s widow and herself a mother of three young children, was the sole survivor of an IRA ambush in which four people, including a woman, were killed.

The ambush happened at the entrance to Ballyturin House, about three miles south-east of Gort, at about 8pm on Sunday 15 May, 1921. The target was the Gort RIC District Inspector Cecil Blake, a former Royal Artillery soldier who had developed a fearsome reputation in south Galway. He and his wife, Eliza, and two army officers were shot dead by a large group of IRA men who had lain in wait around the gatehouse all afternoon while the guests played tennis.

The IRA Commandant, Joseph Stanford of the First Battalion of the South Galway Brigade, said that one of the army officers, Captain Cornwallis, was shot dead when he opened fire after the raiders had shouted ‘Hands Up’ and expected the women to leave the car in which they were all travelling. The other army officer, Lieutenant McCreery, was shot in the back seat where he had been sitting beside Margaret Gregory, who had got out of the car and crouched behind a back wheel. The ambush claimed a fifth victim when an RIC Constable, John Kearney, was fatally wounded after police and military arrived at the scene. In one account ‘shots rang out and Constable Kearney fell from the lorry’, but Joseph Stanford and others said that he was shot by other RIC men who suspected him of giving information to the IRA. A single man from Co Kerry, Kearney had been in the police force for 14 years and was about to retire, the IRA believed. According to Stanford: ‘He was one of those RIC men who did not agree with their methods, and they knew it.’ He died from his wounds in St Bride’s Home, a small private hospital in Galway city.

Lady Gregory heard about the Ballyturin ambush while staying with George Bernard Shaw and his wife at Ayot St Lawrence in Hertfordshire. Shaw read about it in the morning newspaper and he told Lady Gregory just before she received a telegram from Margaret which said: ‘Sole survivor of five murdered in ambushed motor’. In her journal, Lady Gregory wrote: ‘It was a bad shock – the thought of the possibilities...And then, though she is safe thank God, it is impossible to know how it will affect her outlook and the life of the children, and through them mine. I was quite broken up – went into the air for a while, and then when I came back, kind G. B. S. made coffee for me and spoke comfortably and wanted me to stay, but I thought I might be wanted at Coole.’

Under the same date, 17 May, she added that a visitor to the house that evening told her that he had had lunch with a man who knew Captain Blake and who described him as ‘a terror’ – a very harsh and violent man, who had gone over (to Ireland) ‘to make it hot’ and was bound to find trouble. He had boasted that he would take the blood of Michael Collins. In a later entry she recorded that staff at Coole told her that Blake and his wife ‘had attacked Father Considine and had a scene with him, in his house.’

The ambush strengthened Margaret’s resolve, growing since her husband’s death, to leave Galway. Lady Gregory wrote in her journal: ‘All seems crumbling, yet I will not leave Ireland and will try to hold Coole for a while at least that the darlings (her grandchildren) may still think of it as home.’ On the same day, 22 May, she added: ‘It is peaceful here today after the shock last week, and I have more time to think, and I feel I ought to go home lest the children should be brought away from my keeping.’

On her return to Coole in June, Lady Gregory spent a number of days seeking appointments with top military and police officers in Galway city. She managed to persuade them to overturn a request that Margaret would help to identify anyone who had taken part in the Ballyturin ambush, either from photographs of suspects or in an identity parade in Galway Gaol. She and Margaret believed that any co-operation would endanger Margaret’s life. Only one of the IRA party had worn a mask. One of them, ‘a sweet boy’ in Margaret’s words, had led her away from the scene.

Lady Gregory wrote later that Margaret’s life had been spared in the ambush because she was a Gregory and because the IRA knew that the 1920 Nation articles had been written by Lady Gregory. In a post dated insertion to her journal she wrote: ‘It was not till later I was told that the day after the ambush she had been sent a message from ‘them’ that she was in no danger, that there never would be trouble here ‘as long as there is a Gregory in Coole’ because of what I had done for the country – I believe my Nation articles though I did not think they were known of.’

The witness statements of the leading ambushers contradicted this. The recollection of Gort IRA Commandant Joseph Stanford, who led the attack, was that Margaret Gregory would have been shot had she exited the car on the other side. He said: ‘This lady did a very foolish thing as she came out of the car on the right, where ‘hands up’ came from and thereby saved her life. She crouched beside the back wheel, so close that we could have touched her with the guns. Had she got out on the other side she would have shared the fate of Mrs Blake.’ IRA Vice-Commandant Patrick Glynn recalled: ‘We concentrated fire on the car, doing our best to save the women in it’. A third IRA man, Thomas Keely, said that Margaret Gregory was ‘fortunately saved’ and that Mrs Blake was ‘unavoidably killed’.

Margaret Gregory had been increasingly determined to leave Galway and Ireland since her husband’s death, but Lady Gregory wanted to keep the grandchildren for as long as possible at Coole, where each of them had been born. Six months after the Ballyturin ambush, and exactly one year after Eileen Quinn’s death, Margaret agreed to let Coole House and demense to Lady Gregory ‘so long as she pays all charges and expenses’ – terms that she later eased .

*****

Lady Gregory’s pain over the Yeats poem was fuelled by its suggestion that her son was happiest when he was away from home fighting in the Royal Flying Corps. She believed that Yeats had been told this by George Bernard Shaw, though not for repetition.

Robert Gregory had joined the Royal Flying Corps via the Connaught Rangers early in the 1914-1918 war. He was awarded a Military Cross and a Legion h’Honneur for conspicuous bravery and he was said to have shot down 19 German planes – a claim repeated by Yeats in the opening two lines of Reprisals.

The Connaught Rangers regiment was nicknamed ‘The Devil’s Own’ by the Duke of Wellington, who is reputed to have said that he had hanged and flogged more of them than of any other regiment, but that there were no other soldiers that he would have preferred to lead into battle.

Hundreds of Connaught Rangers staged a mutiny in northern India in mid-1920 in protest against Black and Tan atrocities in Ireland. Two privates were shot dead and 14 others were sentenced to death. Winston Churchill confirmed in the House of Commons in November that 13 of the sentences had been commuted and that the sentence on the remaining soldier was carried out on 2 November.

The Connaught Rangers’ regiment was being disbanded by the new Irish Government in early 1922 when two of the last and least-remembered atrocities of the War of Independence took place on the same night in two hospitals in Galway city. The first happened in St Bride’s Home on Sea Road, where RIC Constable John Kearney had died from the wounds he sustained on the night of the Ballyturin ambush. Exactly 10 months after that ambush, two other RIC men who had been stationed in Gort were among three men who were shot dead in their hospital beds on the night of 15 March, 1922. This was six days after the RIC had withdrawn from Galway and more than a month after the British forces departed from Galway’s main army barracks at Renmore on 13 February. It was three months after the Anglo-Irish Treaty had been signed and more than nine months after the Truce between the IRA and Crown forces.

Sergeant John Gilmartin and Sergeant Tobias Gibbons were

convalescing in separate rooms in St Bride’s Home, having

been too ill to be discharged when all the other RIC men left

Galway the previous week.

Four men entered the building through the unlatched front door and

went directly to the room that Sgt Gilmartin was sharing with

another man. Two guarded the door while the other two went inside

shouting ‘Hands Up’. Asked if he was a policeman,

Gilmartin replied: ‘I was, but not now’. He was shot

four times after he had said an Act of Contrition and pleaded

‘Oh God, sure you are not going to do this’.

The gunmen then went to the room occupied by Sergeant Gibbons and an RIC Constable named McGloin. They shot Gibbons six times. His body had two wounds on the face, one near the mouth and one near the left eye. He had three bullet wounds on his back and one on the front of his chest. There was also a bullet wound on each of his hands. Constable McGloin was hit in the eye, arm, wrist and thigh, but survived. Doctors told the inquest next day that the two sergeants died instantaneously. The killings happened while the nurses and other staff were having supper. The matron, Miss Coffey, told the inquest that the front door was always slightly open to save the maids trouble. The jury returned verdicts of murder by persons unknown.

Sergeant Gibbons, who was from the Fair Green, Westport, Co Mayo, was unmarried and aged about 43 years. He had been sent to Gort after being stationed in Tuam for many years. Sergeant Gilmartin, from Co. Leitrim, left a wife and two children. He had been sent to Gort from Oughterard, where he was stationed at Camp Street. Their murders happened in ‘one of the last attacks to cause a fatality of a serving officer in the south of Ireland’, according to Richard Abbott in Police Casualties in Ireland 1919-1922.

A verdict of murder by a person or persons unknown was also recorded at the inquest into the death of Patrick Cassidy, a married farmer and Congested Districts Board official from Ballyhaunis, Co Mayo, who was shot dead on the same night as the two RIC sergeants in Galway’s Central Hospital, where he was being treated for wounds sustained in an attack on him at his home a month earlier.

‘Horrifying occurrences at Galway hospitals’ was one of the headlines in the Connacht Tribune that weekend. ‘Two sergeants of the RIC and one civilian riddled with bullets’ was another.

Under its main headline ‘Sick Men Shot’, the paper reported that about half-an-hour after the St Bride’s Home killings ‘three masked men entered the workhouse hospital ward, walked up to the bed where Patrick Cassidy lay, and asked him if he was Cassidy’. The report went on:

‘Upon being assured that he was, they fired two shots at him, one entering the head, the other entering the throat. He appears to have struggled, for when the matron rushed to the scene, she found the patients in a state of horror and Cassidy lying at the foot of the bed, apparently dead, in a pool of blood.’

St Bride’s Home, where the RIC men died, is just three doors away from No 2 Montpelier Terrace, where Fr Griffin lived. A plaque on the pavement outside the house commemorates his abduction. He is also commemorated in large monuments outside Loughrea Cathedral, where he was buried, and near Barna, where his body was found, as well as in the name of the cut stone catholic church in Gurteen, Ballinasloe, where he was born. Fr Griffin Road, linking Galway city to Lower Salthill, is named after him, as are Fr Griffin Place, Fr Griffin Avenue and one of the city’s most prominent GAA clubs. The RIC men who died in St Bride’s Home are not commemorated, and barely remembered, in the city.

The three Galway city hospital deaths were investigated by formal inquests which were re-introduced by the new Irish government in early 1922, but hundreds of War of Independence deaths were dealt with by military inquiries that had been introduced under the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act, 1920, which suspended Coroners’ Courts in ‘disloyal’ counties including Galway. These were sometimes called Tribunals and they were presided over by three military officers who need not have had any legal or medical training.

Military Courts were ‘a perversion of Coroners’ Courts’ and the inquiry into Eileen Quinn’s death took place with ‘indecent haste’...‘unseemly haste’ , according to Professor Gerard Quinn, emeritus professor in law at NUI Galway and a grandson of Eileen Quinn. She was shot on Monday and the Court of Inquiry sat on the following Thursday – the day of her funeral. Her widower, Malachi, had to attend her funeral, in St Colman’s Church, and the Court of Inquiry, in Gort Military Barracks, on the same day. She is buried in Kiltartan Cemetery.

Under the 1920 law, witness statements could be taken and the presiding officers could visit the scene of a suspicious killing, but the presiding officers at the Eileen Quinn inquiry chose not to visit the scene. Among other things, they would have seen that the road outside the Quinn house was dead straight for at least half-a-mile in each direction, contrary to the auxiliaries’ testimony that they fired only warning shots for fear of being ambushed as they approached a bend on the road.

Set in South Galway against the backdrop of one of the bloodiest months of the Irish War of Independence, Reprisals tells the dramatic story of the short life and tragic death of 24-year-old Eileen Quinn who was shot outside her home in 1920. Produced by Orla Higgins & Sarah Blake for RTÉ Radio 1.

The failure of the RIC chief constable in Gort to take a formal statement from Eileen Quinn as she lay dying was ‘an absolute dereliction of duty’ on his part, according to Professor Quinn, who is also a qualified barrister-at-law and a graduate of Harvard Law School. ‘It (the court of inquiry) was rigged’, he said.

Counsel for the Crown objected to the inquiry accepting as evidence Mrs Quinn’s dying statement to Fr Considine that she was shot by ‘police’. The newspapers were not permitted to identify any police or military witnesses. ‘Only witnesses and friends of the deceased were allowed into Gort Military Barracks, where the military inquiry was held on Thursday, and these obtained admission to the inquiry only when they gave evidence’, the Connacht Tribune reported . ‘The Press was cautioned not to give the witnesses’ names, but on inquiring, were informed civilian witnesses might have their names published’, it added. Auxiliaries from the troop that shot Eileen Quinn were said to have been marching up and down the corridor outside the inquiry room, presumably to intimidate witnesses.

The killing of Eileen Quinn, one of Yeats’s ‘other cheated dead’ was seen as a reprisal for the fatal shooting of Constable Timothy Horan two days earlier a few miles away from her home. Yeats initially titled his poem Reprisals, but he crossed out that word and replaced it with To Major Robert Gregory, airman on the typescript he sent to Lady Gregory. The poem urged Robert Gregory’s ghost: Yet rise from your Italian tomb/Flit to Kiltartan Cross, before adding in its final two lines:

Then close your ears with dust and lie

Among the other cheated dead.

Yeats’s widow, George, eventually allowed the poem to be published, under its original title, in the journal Rann: An Ulster Quarterly of Poetry in 1948, having earlier refused permission because Robert Gregory’s only son, Richard, was fighting in World War Two. She permitted its publication to coincide with the return to Ireland of Yeats’s remains in September 1948, nine years after his death in the south of France. Before burial at Drumcliffe, in Co Sligo, the remains had been carried to Galway port on the Irish naval vessel Macha. On the road journey to Sligo, the cortege was able to pass by Galway’s New Cemetery, where Lady Gregory, perhaps Yeats’s closest friend, was buried in 1932.

Reprisals against civilians did not become an official war crime until the Geneva Conventions of 1949, a year after the Yeats poem was published. In early 2020 as the centenary of the Quinn and Horan deaths approached, grandsons of both victims met. Professor Quinn wrote afterwards: ‘The events of 1920 are very raw and immediate to both of us. But the distance between then and now gives us a fresh chance to see the humanity of all sides and to bemoan all human loss and suffering, no matter whose ‘side’ it is on’.

Ray Burke is a former Chief News Editor with RTÉ News & Current Affairs. His latest book, Joyce County: Galway and James Joyce, was published by Currach Press in 2018.