Mountjoy hunger strikers released after general strike

Dublin, 21 April 1920 - 66 hunger-striking Sinn Féiners were released from Mountjoy Jail on 14 April. The men had been on hunger striker since 4 April as a protest against the refusal of authorities to recognise them as political prisoners. They demanded that they be tried or released, and the government relented.

The decision of the British authorities to release the men has been widely welcomed. There is a consensus view that, had any of the prisoners died in custody, the situation in Ireland, bad as it is, would actually have gotten worse.

The climb-down by the authorities is also viewed as affording some breathing space for the new Dublin Castle administration.

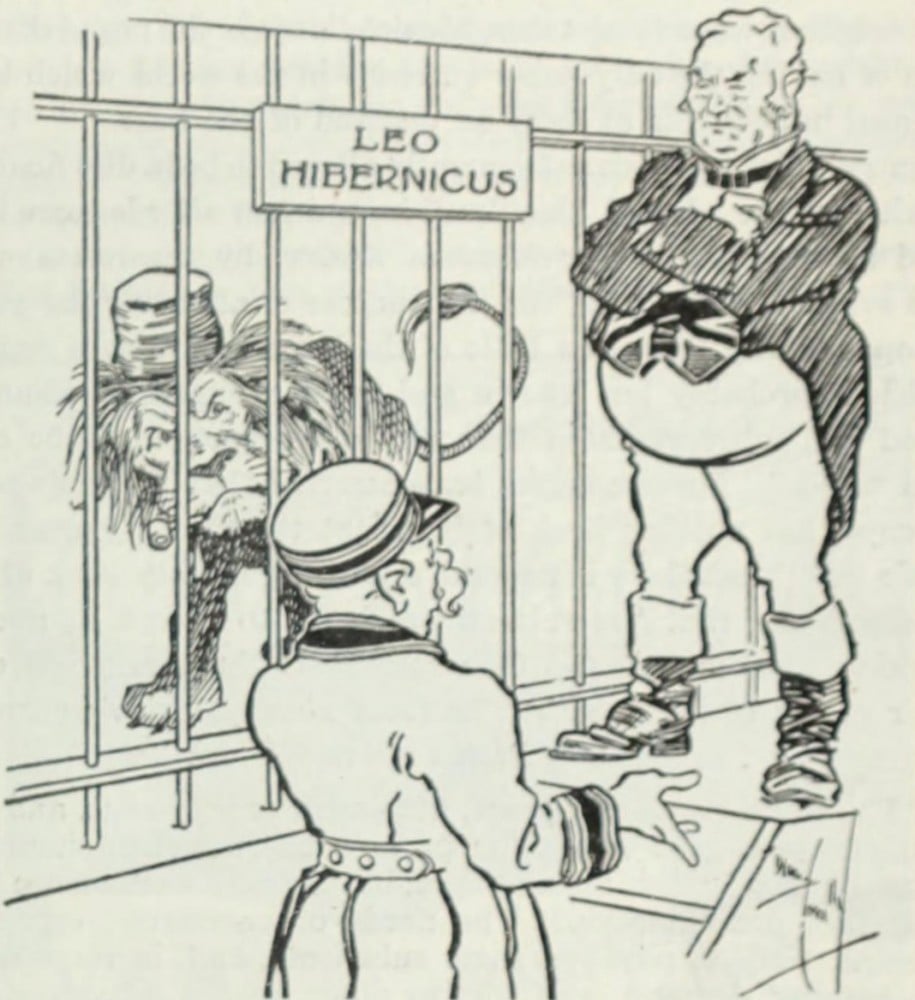

A cartoon featuring Leo Hibernicus, the Irish Lion that originally appeared in the Bulletin, published in Sydney, Australia. The caption reads, 'John Bull: What's the matter with the Irish Lion this morning? He's been going on like this for six hundred years, but I never saw him worse. Keeper: Well, sir, I've been thinking it over, and it just struck me that maybe he wants to get out.' (Image: The Literary Digest via the Internet Archive)

The Times newspaper has said that if the government had persisted ‘in their original intention a situation of the utmost gravity must have arisen in Ireland. Dubliners have not forgotten the cumulative strain of the series of executions which followed the Easter Rising of 1916.’

Andrew Bonar Law, government minister, informed the House of Commons that the men have been released on parole, however it is understood that none of the prisoners made a verbal or written commitment prior to their release, which is a usual condition for this type of release.

Regardless of how the decision is presented, Mr Bonar Law has

performed a volte-face on the hunger strike question, as

he had previously declared that the prison rules must be

implemented and the hunger strikes be allowed to take their

course.

Speaking in the House of Commons, Brigadier General Henry Croft

cited past experience in questioning the wisdom of the releases.

‘Is it not a fact’, he wondered, ‘that on the

last occasion that a large number of prisoners were released in

Ireland it was the starting point of crimes and atrocities?’

Public support for the prisoners

In recent weeks, pressure has been growing on the government to

give in to the prisoners. One of the most obvious manifestations

of this pressure came in the form of a general strike held on 13

April which brought business across much of the country to a halt.

An estimated 60,000 workers including postal employees, bank officials, tramway men took part.

Scenes from the strike: L - the Lord Mayor of Dublin (marked with an X) speaking to crowds at the prison gates. R - a more boistrous crowd at the barricade (Images: Irish Life, 16 April 1920)

The Punchestown Races were abandoned. In Enniscorthy, red flags and republican flags were waved as people marched through the town in a procession to a public meeting. In Skibbereen, children marched through the streets singing the ‘Soldier’s Song’.

The Irish Independent described the strike as the ‘united and solemn protests against the Mountjoy scandal. No other government save the British would be so conscienceless as to set at defiance such a national protest.’

The catholic bishops weighed in by making it clear that responsibility for the fate of the prisoners rested with a government ‘that substitutes cruelty, vengeance and gross injustice for equity, moderation and fair play.’

The general strike was called off the following day, 14 April, by Thomas Johnson of the Irish Labour Party. Mr Johnson thanked the workers and said that they had ‘shown an example to the world of how Labour might make its will effective – an example of solidarity without parallel.’

In urging workers to go back to work, Mr Johnson noted that the absence of traffic had deprived the towns of Ireland of food and he asked that consideration be given to the preservation of supply lines and to protect people from the behaviour of profiteers.

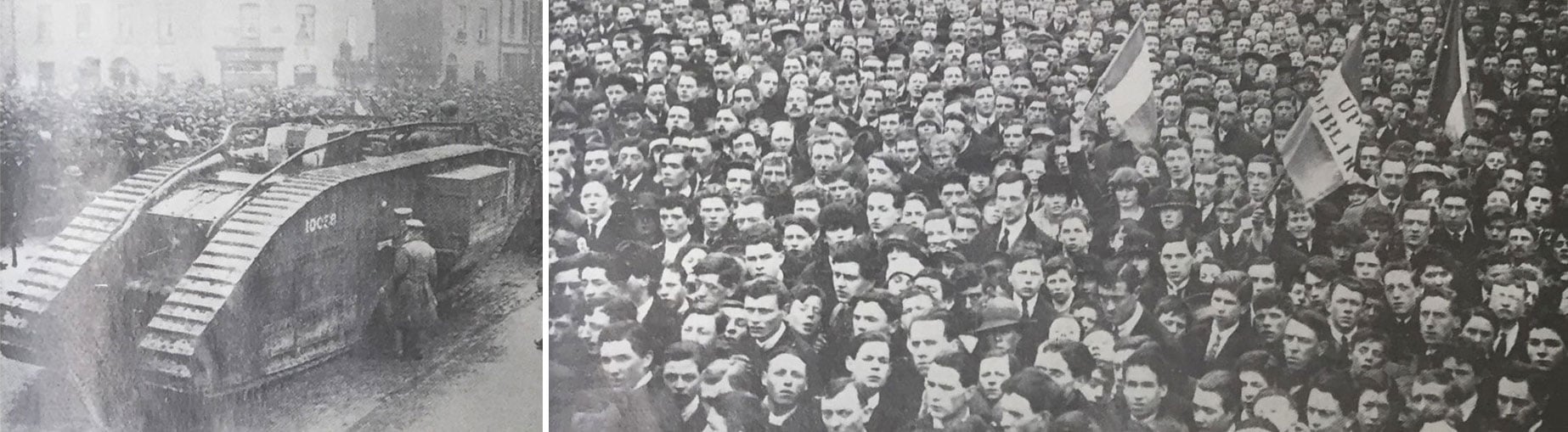

Scenes from the strike: L - a tank maintaining law and order on the streets. R - a portion of the huge crowd that recited the rosary outside the prison (Images: Irish Life, 16 April 1920)

The conclusion of the hunger strike in Mountjoy does not affect the situation in Wormwood Scrubs where 98 Sinn Féin prisoners are now on hunger strike owing to the refusal of the authorities to grant leave on parole to some of the prisoners to visit immediate relatives who have been seriously ill.

One prisoner had applied to visit a child who was reported to be sick. The application was refused and the prisoner subsequently learned that the child had died.

In a further development on the prisons issue, the Irish executive in Dublin has issued new regulations which allow for the different treatment of political and non-political prisoners. The regulations also provide detail on what offences cannot be defined as political in nature. These include homicidal assaults or similar offences against the person; they also include burglary, cattle driving and offences against property; they include rioting or having firearms, explosive or being involved in ‘unlawful assembly’ and ‘speaking or writing words inciting or encouraging persons’ to commit any of these offences.

[Editor's note: This is an article from Century Ireland, a fortnightly online newspaper, written from the perspective of a journalist 100 years ago, based on news reports of the time.]