Labour Radicalism & Irish Revolution in Australia

By Jimmy Yan

In October 1920, two political radicals who rose to prominence out of the Australian anti-conscription movement attended the mass funeral of the late Terence MacSwiney in London. At the helm of the cortège was the well-known Daniel Mannix, Melbourne’s firebrand Catholic Archbishop who delivered the last sacraments for MacSwiney in Brixton Jail. Standing on the sidelines of the procession was Tom Barker, a leading figure in the Sydney Local of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), recently deported from Australia, who had earlier completed a globe-hopping tour of Latin America. Barker described the crowd around him as a 'magnificent sight', in which 'the Sinn Féin colors had a glorious airing … through the streets of London.' English-born, and non-Irish, and with no prior connections to Irish nationalism, the radical syndicalist Barker makes for an unlikely starting point for an investigation of the ‘Irish Question’ in the Pacific. Yet in calling into question bounded histories, his momentary encounter with the global Irish revolution exemplified both the fluidity and eclecticism of this contest: one that permeated networks of radicalism broader than the Irish nationalist movement itself.

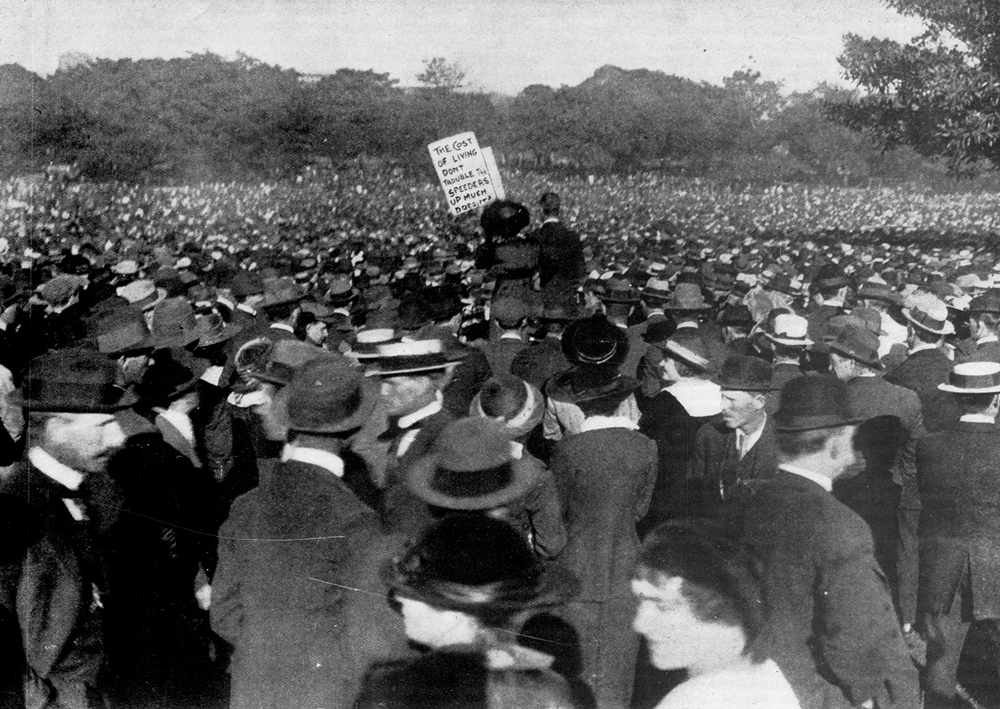

The most important of these sites of contention was the white Australian labour movement, a formation that broadly conceived, comprised trade unions, the Australian Labor Party, smaller radical groupings beyond it, the Women’s Peace Army, and a disparate radical intellectual counterculture. The ‘Irish question’ figured, within radical spaces as diverse as the Sydney Domain and railway union halls, as a live political question that catalysed public meetings, petitions and telegrams from afar. Radical imaginings of Ireland were, at the same time, part of an ambivalent contest over ‘empire’ and ‘self-government’ within a labour movement committed to racial exclusion. As a directly ‘international’ question, ‘Ireland’ politicised both supporters and opponents of State Aid for Catholic schools, a largely separate issue that divided the Labor Party from the Catholic hierarchy for most of the early 20th century. Tensions between the labour movement and the nationalist government of Billy Hughes over the ‘Irish question’ were exacerbated in November 1920 with the expulsion of Labor MP Hugh Mahon, a former Land League activist, from parliament for publicly supporting MacSwiney’s hunger strike. Internal debates over Ireland in the Labor Party itself culminated in 1921 within a swathe of conference resolutions for Irish self-determination: two years after the New Zealand Labour Party, and a year after the British Labour Party.

With the collapse of the pro-Redmond United Irish League in 1917, the re-emergence of Irish nationalist campaigning in Australia invigorated an overlapping web of Catholic and Irish, as well as labour, associational networks. Understood as a social movement, the labour movement provided both a political repertoire and a mobilising structure for extra-parliamentary formations including the Self-Determination for Ireland League of Australia (SDILA), formed in 1921. Like its counterparts in Canada and Britain, the SDILA was a broad movement in which labour radicals played a central role as both orators and organisers. A layer of openly Irish nationalist Labor politicians, including Frank Brennan, whose wedding William Redmond attended in 1913, embraced Irish republicanism after 1918 and were actively involved in the SDILA. The Queensland Labor Government of TJ Ryan lent its weight to Irish nationalist demonstrations and cabled a resolution to Eamon de Valera in March 1918 opposing conscription in Ireland.

The relationship of labour radicals to the 'Irish question' was, at all times, political and contested instead of an organic reflection of fixed ethnic identities. Although Catholic Irish settlers were prominently represented in the ranks of the Labor Party, the terrain of contention surrounding Irish independence defied bounded metaphors of an ‘Irish presence’ in the labour movement. The radical pressman (and future prime minister) John Curtin was the nephew of a Fenian, Cornelius Curtin, but was one of a handful of Labor Party conference delegates to have opposed Irish self-determination in 1921. By contrast, radicals who claimed no Irish ethnicity, including the English-born Labor MP Frank Anstey, emerged as among the most vocal Australian proponents of Irish independence. In 1919, Anstey travelled to Dublin as a member of a Dominion Press Delegation and met with leading figures in the Irish Labour Party and Sinn Féin including Thomas Foran, Eoin MacNeill and Harry Boland.

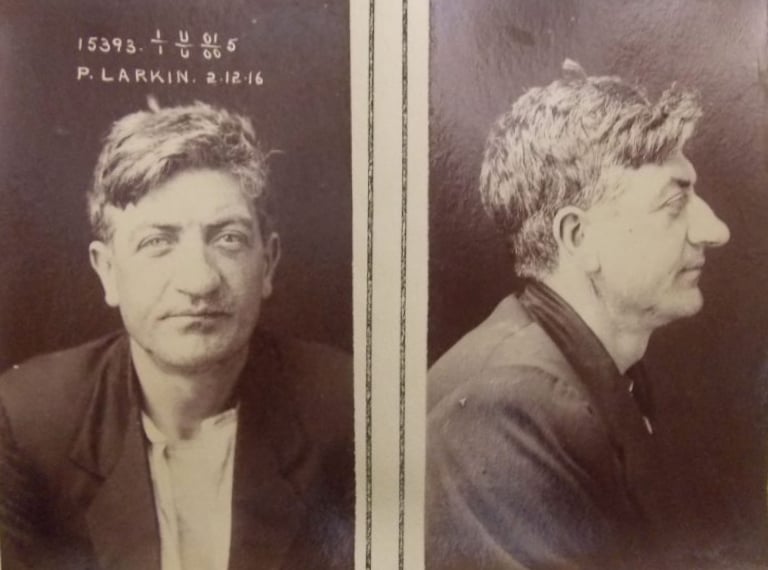

The peripatetic lives of political 'globe-hoppers’ offer an insight into radical connections with Ireland ‘below’ the nation-state. The most prominent member of the Irish revolutionary generation to have lived in Australia was the seafarer Peter Larkin, the brother of Delia Larkin and Jim Larkin, whose seven-year-long antipodean sojourn between 1915 and 1922 broadly overlapped with the Irish revolution itself. Like his famous siblings, Larkin emerged out of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) during the Dublin Lockout, and following both its defeat and the outbreak of war, worked his passage to Sydney in 1915 aboard an army transport vessel. Upon arrival, he joined the IWW and became a well-known anti-war orator, and during the first conscription referendum in September 1916, was arrested with eleven other IWW members as part of the ‘Sydney Twelve.’ As a self-described ITGWU member abroad whose political outlook was formed in multiple national contexts, he took a pronounced interest in Irish independence itself, and regularly lectured on the ‘Historical Basis of the Irish Rebellion’ to crowded halls. Writing from Long Bay jail in Sydney to Enniskillen-based trade unionist Thomas O’Byrne, Peter Larkin conveyed an unequivocal sympathy for the Easter Rising, and claimed, in a ‘Larkinite’ political language, that it was for the “faith of James Fintan Lalor” that “boys under Pierce [sic] and Connolly gave the [sic] lives.”

Peter Larkin, the brother of Delia and Jim Larkin, was a well-known orator on the 'Irish question' in Australian radical spaces and a member of the Industrial Workers of the World in Sydney between 1915 and 1922. (Image: New South Wales State Archives, NRS2467)

To what extent did such ‘Ireland-Australia’ connections produce an ‘Australian question’ in the Irish labour movement? As a radical who lived ‘between’ national contexts, Peter Larkin’s engagement with the Irish Revolution in Sydney was shaped by long-distance ties with the Irish labour movement itself during its convergence with the republican movement. From Sydney, he corresponded with Delia Larkin, who briefly contemplated migrating to Australia, and in May 1918, called a protest meeting in Dublin demanding the release of the Sydney Twelve. Drawing on her ‘Australian’ connections, Delia Larkin organised this demonstration with the involvement of Liverpool-based IWW deportees Jock and May Wilson, formerly of Sydney. This campaign was, beyond an expression of solidarity for Sydney Twelve, an outgrowth of the political culture of revolutionary Dublin itself. After a heavy police cordon prevented the meeting from taking place in its advertised venue of Mansion House, it reconvened at the Irish Workers’ Club in Langrishe place in defiance of a ban.

These political border-crossings were, as such, not limited to Irish settlers in Australia, but also included Australian radicals who visited revolutionary Ireland itself as political travelers. Harry Arthur Campbell, an Independent Labour Party (ILP) organiser in Glasgow of New Zealand background and Australian birth, visited Ireland in October 1920 as an ‘independent observer’ of the War of Independence and published his observations in a six-penny pamphlet, The Crucifixion of Ireland. His first-hand account of the unfolding war featured graphic descriptions of police raids on civilians, including on O’Connell Street. In the same months, Campbell was an increasingly vocal internal dissident in the British Labour Party over the ‘Irish Question’ and became sympathetic to the nascent Communist movement.

Campbell was a self-styled ‘Australian’ in the

metropole, but this political identification carried with it the

logic of the ‘global colour line’. He combined his

support for Irish independence with a commitment to the White

Australia Policy.

For the many other trade unionists whose lives remained sedentary,

expressions of solidarity from afar offered an outlet of

long-distance participation in the Irish revolution. In January

1921, railway workers in the state of Victoria became embroiled in

controversy over the shooting of three Irish railway workers in

Mallow by the ‘Black and Tans.’ Weeks later, the

Australian Railways Union (ARU) passed a resolution at its state

conference condemning the 'hired assassins of the British

Government.' Following a backlash from Empire loyalist and

ex-soldier organisations, the state government dismissed the mover

and seconder of the resolution, Alex Morrison and Tom Wilson, from

the railway department. Neither Morrison nor Wilson however, was

Catholic or even Irish. Both were Protestants of Scottish

background. Their stance expressed an

‘internationalist’ solidarity for members of a

'kindred organisation in another country' - the National

Union of Railwaymen - instead of attachments to homeland or

diaspora. Connections within the Anglophone labour movement itself

thus gave form to new networks of solidarity that linked Mallow

and Melbourne.

Far from a solipsistic metaphor for ‘Australian’ national concerns, the global Irish revolution produced a tangible contest within the Anglophone radical world that upended and reforged existing political solidarities. As a facet of the post-war international situation, the Irish revolution was a thoroughly modern social movement that reached Australia by sea, telegram and print: within actual cross-border connections instead of cultural essences. In an Australian labour movement that remained majority ‘non-Irish’, albeit outwardly racially exclusionary, the ‘Irish question’ meshed with broader contexts of political radicalism in highly integrated urban spaces. As the near encounter of Tom Barker with Daniel Mannix at Euston station in the autumn of 1920 brought to light, these contentious routes produced some unlikely convergences in their impact 10,000 miles from the GPO.

Jimmy Yan is a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Melbourne. His research examines connections between the Irish revolutionary period, transnational social movements and settler-colonialism in Australia between 1912 and 1923.