Irish Volunteers launch their own newspaper

Read the first edition of 'The Irish Volunteer' and learn about its historical importance with Dr. Conor Mulvagh, UCD

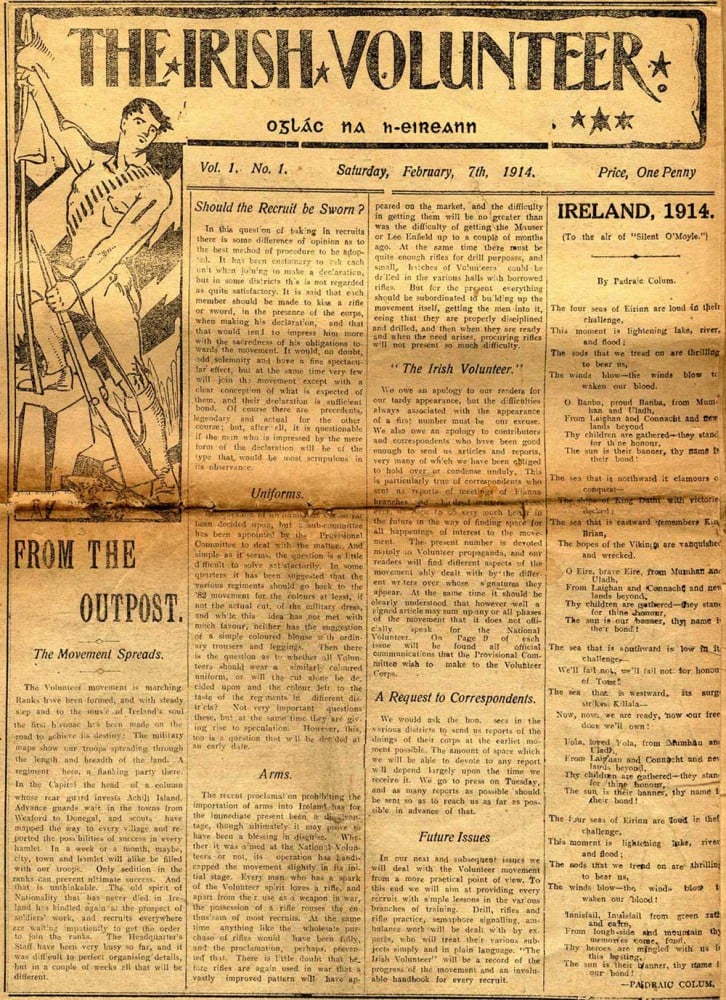

On 7 February 1914, the Irish Volunteer movement launched its official newspaper, the eponymously titled The Irish Volunteer. A PDF version of first edition, courtesy of the National Folklore Collection at UCD, can be read in full by clicking on the image below.

What was The Irish Volunteer and what function did it

serve?

The Irish Volunteer was a weekly newspaper primarily

aimed at the membership of its namesake, an organisation which had

been founded by Eoin MacNeill in November 1913.

A single, four-page paper called the Volunteer Gazette had been issued in December 1913, but this was never intended to be continued as a periodical. On 7 February, the first issue of The Irish Volunteer was in print. Along with providing news and political commentary, it had an important official function in disseminating official orders and announcements, especially to the provincial units.

Who was behind The Irish Volunteer?

William Sears, editor and one of the directors of the

Enniscorthy Echo, first proposed the idea of publishing a

newspaper for the Irish Volunteers in January 1914. The

Enniscorthy Echo was an advanced nationalist paper with

Sinn Féin links going back to 1907/8. The provisional

committee of the Volunteers accepted Sears’ offer, and a

member of the Echo’s staff, Laurence de Lacy, was

appointed editor of the new publication. All proofs of the paper

were approved by the provisional committee of the Irish Volunteers

- namely: Eoin MacNeill, L.J. Kettle, John Gore, and The

O’Rahilly. In the Bureau of Military History, Bulmer Hobson

identified Laurence de Lacy as having been a member of the IRB in

this period. As such, de Lacy’s editorship of

The Irish Volunteer constitutes a further element of the

IRB’s infiltration of the Irish Volunteer movement.

What challenges did The Irish Volunteer face in its

early history?

When the volunteers split in September 1914 over the question of

participation in the war effort,

The Irish Volunteer sided with Eoin MacNeill. The

relative unpopularity of MacNeill’s faction and the

emergence of a rival Redmondite publication, the

National Volunteer, in October, were two key factors in

the Enniscorthy Echo’s decision to cease

publication of The Irish Volunteer in October 1914.

Wartime censorship also played its part in reducing the

profitability of the paper. Titles such as the

Enniscorthy Echo and The Irish Volunteer were

explicitly identified as ‘extreme’ newspapers in Royal

Irish Constabulary police reports.

What happened to The Irish Volunteer after the

split?

Following its first closure, The Irish Volunteer was

revived in a renewed format in December 1914 with MacNeill

identified on the masthead as editor of the paper. However,

Hobson later claimed that the majority of the routine work fell to

him and that MacNeill’s editorship was largely titular and

consisted of writing the ‘notes’ on the front page of

the paper; that is, admittedly, an important aspect of the

publication. The final issue of the paper appeared on 22 April

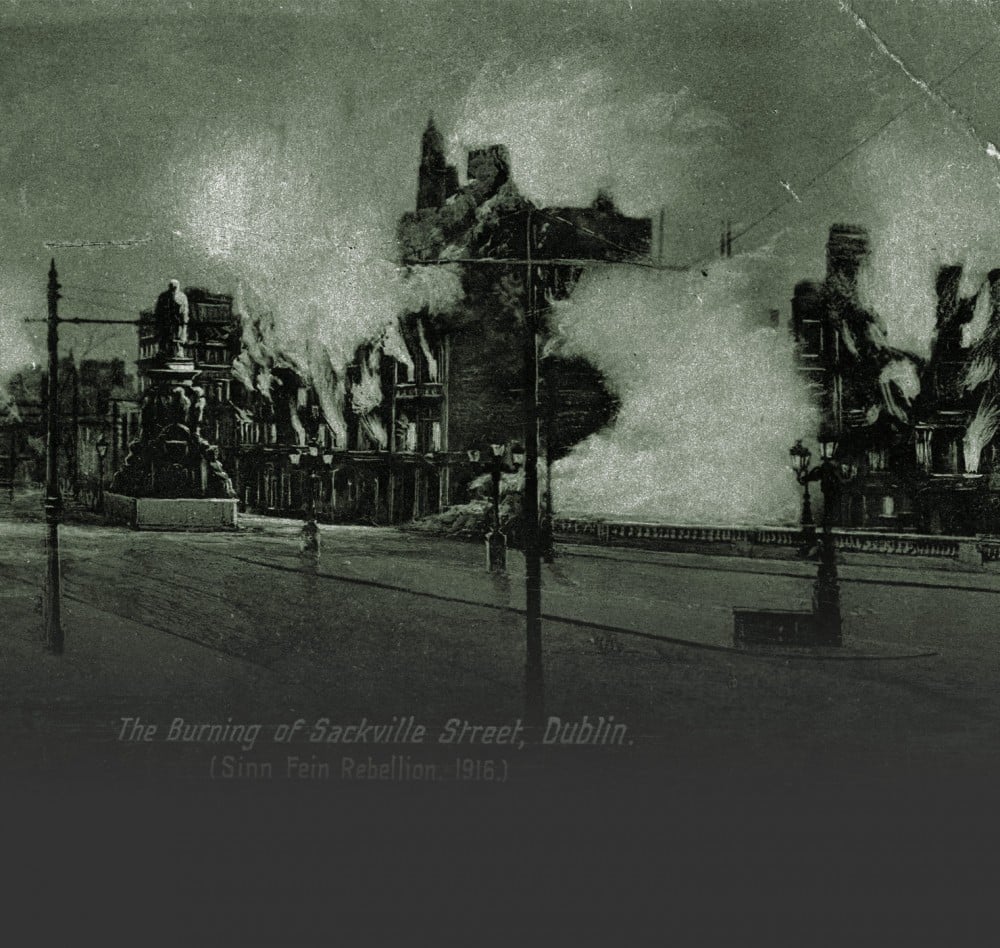

1916, the day before Easter 1916. Given the confusion that

abounded in Ireland by that point, this issue of the paper is an

extremely valuable and significant historical source.

What happened to The Irish Volunteer after the 1916

Rising?

After the Rising, The Irish Volunteer, the

Enniscorthy Echo, and even the Redmondite

National Volunteer ceased publication for a time.

Laurence de Lacy, still involved with

The Irish Volunteer, went on the run. To give a sense of

the government clampdown, the majority of the

Enniscorthy Echo’s staff were arrested and interned

after the Rising. A successor paper to

The Irish Volunteer, under the Irish version of the title

- An t-Óglách - appeared in

August 1918. However, this paper was even more firmly under the

command of the Irish Republican Army than the Irish Volunteer had

been under the control of the Volunteer executive between 1914 and

1916.

Was there propaganda in The Irish Volunteer and what

form did it take?

The importance of history - as opposed to myth - in the pages of

The Irish Volunteer is an important theme of the paper.

Unlike the Anglo-Irish Literary Theatre’s enthusiasm for the

legends of ancient Ireland, The Irish Volunteer reflects

a strong interest in Ireland’s factual - albeit sometimes

distorted - military past. Figures such as Brian Boru, Owen Roe

O’Neill, and Henry Grattan’s Volunteers from 1782 were

constantly brought into the columns of the paper as examples of

laudable Irish military leaders who had led Irish armies on Irish

soil in the historical past. Eoin MacNeill’s professional

training as a historian points to his probable involvement in

these articles, but many others picked up these ideas and wrote

extensively on the various historical precedents for, and

antecedents to, the Irish Volunteers.

What can this paper tell us about the cultural history of the

Irish Volunteers?

Volunteer anthems and poems in praise of the movement were being

written continuously and many were published in the early issues

of the paper. The volume of this material is at times surprising

for a paper which ostensibly existed to aid volunteer training and

transmit messages to and from headquarters in Dublin. This shows

the clear desire to use the paper for propagandising and boosting

morale within the movement. However, after some time, a notice

appeared on the front (notes) page of the paper urging volunteers

to refrain from sending in songs and poems - much of it of

questionable quality - as the paper’s staff were inundated

each week with this kind of material.

How did advertisers capitalise on the emergence of this new

paper?

Newspaper advertising in the Ireland of 1914 was highly

competitive and innovative. There is a real sense of how lucrative

the emergent volunteer movement was for Irish industries. Playing

on a host of clever marketing strategies, advertisers flocked to

The Irish Volunteer to cash in on the latest wave of

nationalism. One regular advertisement within the columns advised

readers ‘Don’t Hesitate To Shoot … Straight to

Gleeson & Co., For Your Tailoring And Outfitting’.

Another company’s advert simply read: ‘WANTED! 10,000

Volunteers to buy Loughlin’s Irish trade mark

outfitting’. Clearly textile vendors and manufacturers were

quick to cash in on the new market for uniforms. Equally, outdoor

equipment, razor blades, footballs, other nationalist and military

periodicals and books, and even eye-tests for aspiring marksmen,

were products and services that sought to profit from

paramilitarism.

Is there any evidence in the paper that the Irish Volunteers

looked out to the wider world?

Within The Irish Volunteer there is much evidence of the

extension of the movement outside of Ireland. Units were formed in

the United States and in Britain, and their formation and progress

can be charted through a reading of The Irish Volunteer.

Additionally, articles within

The Irish Volunteer occasionally took on a distinctly

international outlook. In the first issue, Roger Casement made a

call for Volunteers to participate as Irishmen in the Olympic

Games which were planned for Berlin in 1916 - an event which never

happened. Similarly, the paper contained several anonymous

articles by Indians living in Ireland which outlined the colonial

policies of Britain in India and made comparisons between Indian

and Irish efforts to gain greater national freedoms.

In summary, how important was The Irish Volunteer in

the context of its time?

By virtue of being a specialist newspaper targeted at members of a

private paramilitary organisation, The Irish Volunteer,

its offshoots and successors, are a rare and particularly

important subset of Irish political newspapers from the

revolutionary decade. The function of

The Irish Volunteer was not merely news or propaganda, as

was the case with other publications. Rather, it had a role in

training the force and delivering messages and orders from

headquarters to the battalions and companies nationwide.

As a mobilising force in keeping Eoin MacNeill’s volunteers united and active after the vast majority of the movement sided with John Redmond’s policy of supporting the war effort in September 1914, The Irish Volunteer played a leading role in preserving the movement that was the backbone of the rebellion in April 1916.

Dr Conor Mulvagh lectures in the School of History & Archives, University College Dublin