Irish independence & Central European small nations, 1918-1923

By Lili Zách

In the early 20th century, the struggle of oppressed small nations for self-determination was shared by Ireland and the subordinated races of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Ireland was in the process of becoming an independent small state with border-related problems, defining her relationship with the wider world and developing diplomatic relations. These were experiences shared by the small states of Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The belief that any small nation like Ireland, oppressed by a dominant neighbour, had the right to self-determination was of key importance throughout the period.

Irish interest in Hungary, the Czech lands and Austria had been present long before 1918. Different regions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire had attracted the attention of Irish travellers, clergymen, politicians, and journalists ever since the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), or even earlier than that. Personal encounters on the continent, as well as news regarding the Dual Monarchy, shaped Irish opinion of the above-mentioned nations. Certainly, the images presented by Irish commentators reflected their own political agendas and were therefore often deliberately idealistic. Nonetheless, they served a specific purpose as they were meant to further Ireland’s interest on the international stage.

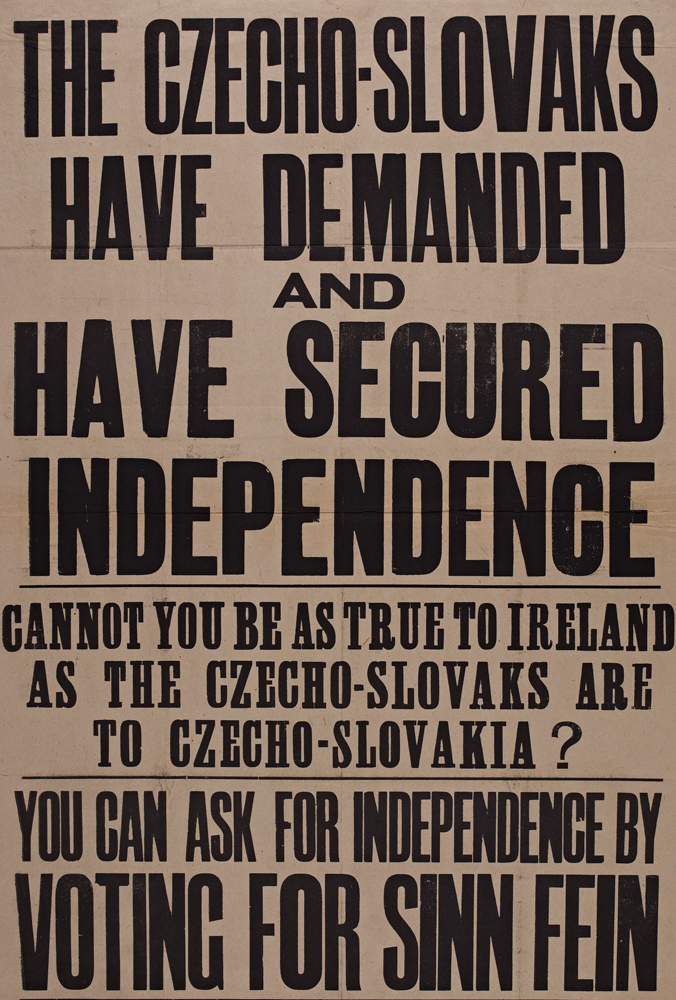

The year 1918 was a watershed in many regards, including the fact that radicalisation of Irish nationalism that followed the Easter Rising culminated in Sinn Féin’s election victory in December 1918. This, together with the transformation of political order in Central Europe, marked a major change in Irish attitudes towards small nations such as the already independent Czechoslovaks and Yugoslavs. In order to support their own political objectives, Irish nationalists highlighted the sharp contrast to Ireland, still under British rule, by noting resentfully that the small nationalities of Habsburg Central Europe had already been granted independence by the victorious powers. Therefore, at this stage, small nations were no longer part of nationalist rhetoric in order to create sympathy like Catholic Belgium did in 1914; rather, they became a tool for republicans claiming the right to Irish independence.

|

|

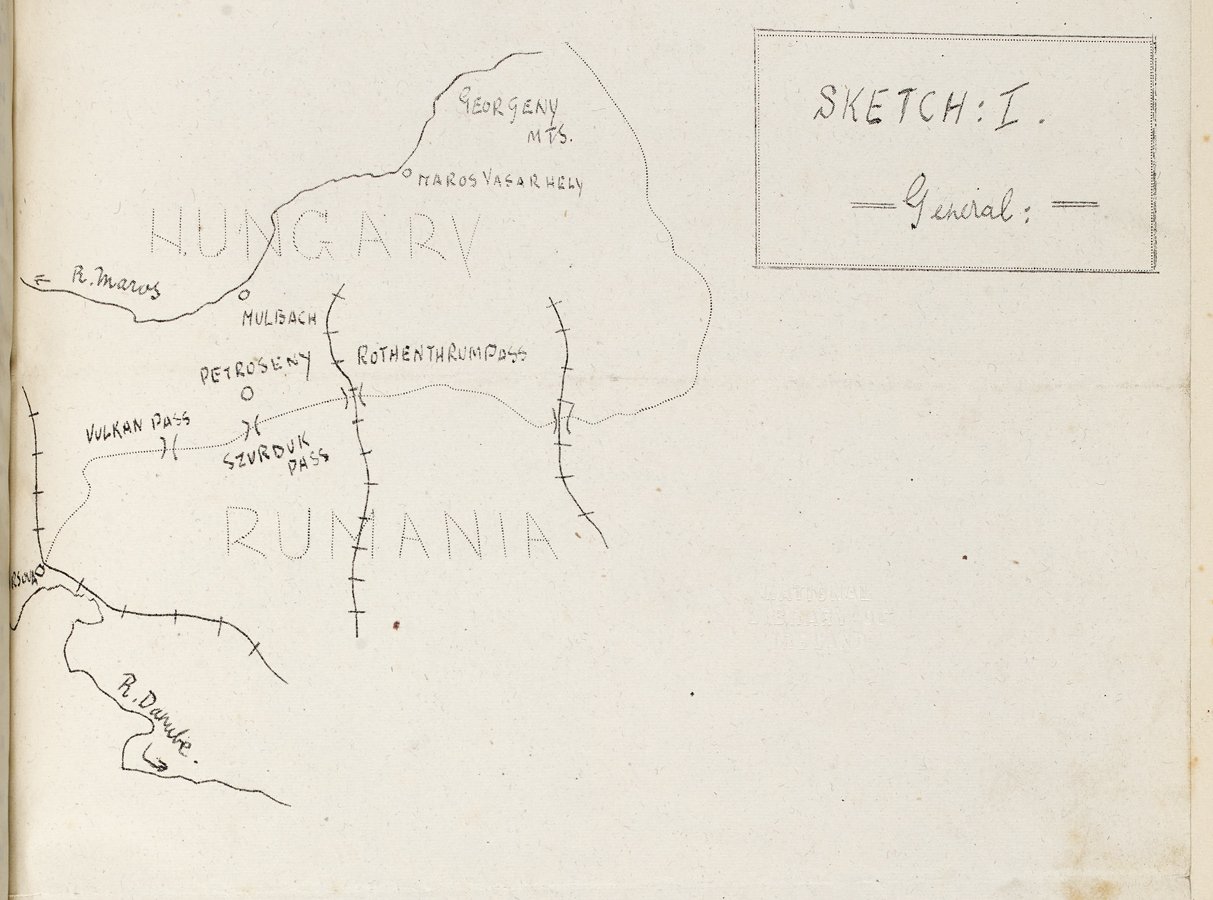

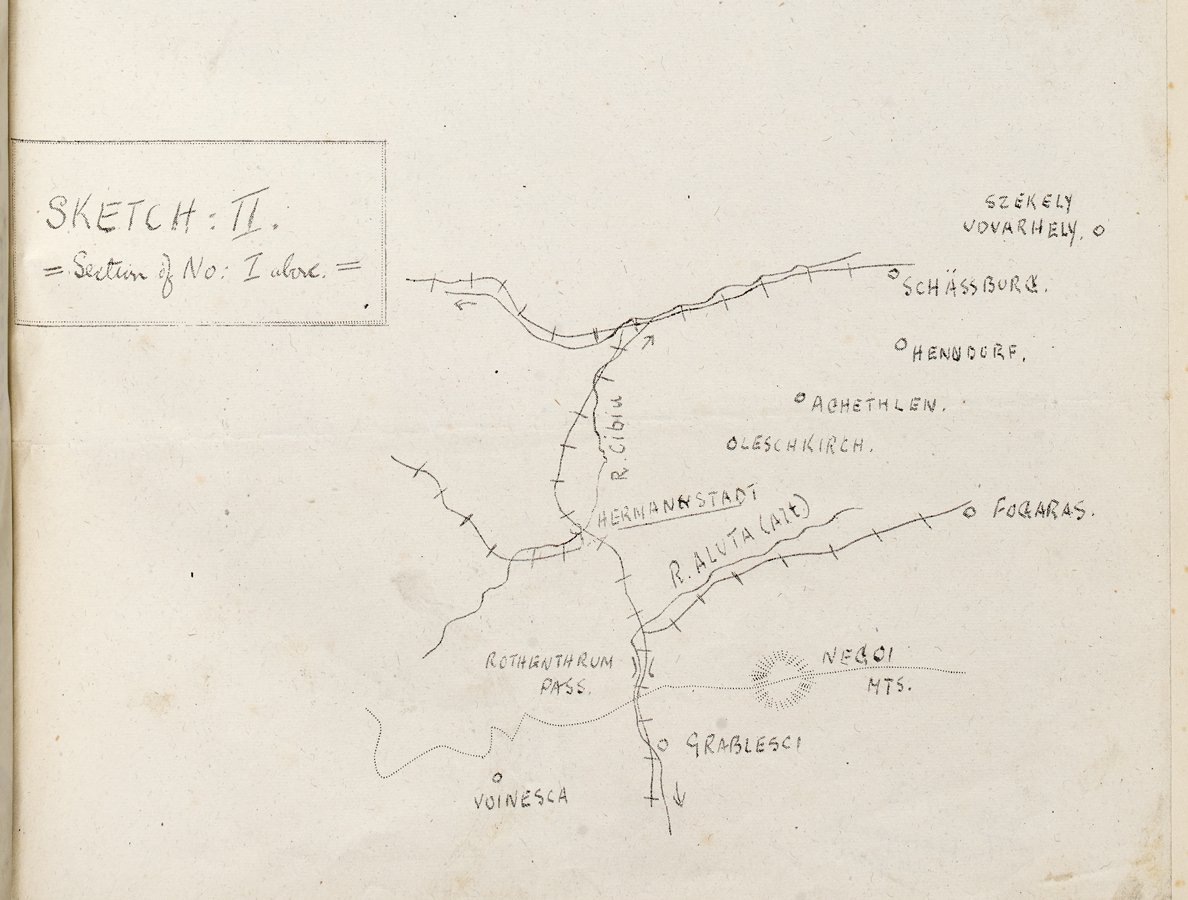

Sketch Maps of Hungary and Romania, [1919-1921]. Contained within collection of General orders from G.H.Q., and documents relating to the activities of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish Republican Army. (Image: National Library of Ireland, MS 900/41)

The political changes that resulted from the redefined borders in Europe after the end of the Great War were inseparable from the formulation of national identities across Europe. Although the circumstances were different in Ireland and in Central Europe, the question of border revisions in the Danube basin sparked Irish interest. The common ground between Ireland and other small states in Central Europe was the revision of treaties (the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the Versailles Peace Treaties, respectively). The birth of independent small states on the former empire’s territory was not without difficulties and the Irish media were aware of this and paid close attention to the region and the potential lessons it could offer for Ireland. In their article of 3 June 1919 entitled ‘The ‘Ulsters’ of Central Europe’, the nationalist daily Freeman’s Journal argued that the independent small states were not only hostile to their old masters but were tied up in fierce mutual rivalries due to their conflicting aspirations. Throughout the year of the Great War, the resemblance between the Irish Ulster and the ‘continental Ulsters’ had been noted by the Jesuit quarterly Studies, as well as the nationalist dailies Irish Independent and Freeman’s Journal. Besides the conflicting interests of the Germans and Czechs of Bohemia, advanced and moderate Irish nationalists found the minority question in Finland, the Balkans, Russian Poland, the South Tyrol, and Alsace comparable to that in Ireland.

Unlike Ireland, independent Austria and Hungary resented their status as small states, which was also in sharp contrast with that of the pride of the Czech small nation, and, after 1918, that of the Czechoslovak small state. The self-image of the independent Austrian small state was associated with its losses, especially its economic losses and its exclusion from the otherwise united German lands. Furthermore, the long tradition of Catholicism was also inseparable from the Austrian small state’s national identity. Standing up against ‘the advance of eastern barbarism’ provided independent Austria with a distinct mission in post-war Central Europe, frequently highlighted by Irish contemporaries as well. Therefore, Catholicism and ‘Germanness’, were of key importance when determining Irish perceptions of Austrian loyalties. Similarly, the image of ‘truncated Hungary’ became the synonym for the Hungarian small state, fixating on the involuntary loss of national territories. The revision of the Treaty of Trianon seemed to echo the trauma of ‘truncated Ulster’ that was present in nationalist Irish rhetoric in the same period. On the whole, looking at other nations for inspiration was a common thread in Irish accounts, especially in relation to the quest for national independence. Certain themes, such as small nations’ right to self-determination, or the issue of boundaries, closely associated with the ‘minority problem’ in Habsburg Central Europe, for instance, persistently defined relationships and political changes in the region, according to Irish commentators. Therefore, the renewed conflicts between the state-forming nationalities and the national minorities in the self-declared ‘nation-states’ remained at the centre of Irish attention after 1918, during the years of the War of Independence as well.

Irish accounts between 1918 and 1923, both first-hand and second-hand, indicated awareness of the social and political transformation of Central Europe from the perspective of small nations. The significance of Catholicism, the national language, regional loyalties (especially in Bohemia and the South Tyrol), and the right to self-determination proved to be the most frequently discussed issues. Central European boundary issues in parallel with the ‘Ulster problem’ remained in the centre of Irish well after the final settlement of the Irish border, and the decision of the Irish Boundary Commission (or the lack thereof) in 1925. Therefore, Irish comments on Central European parallels serve to shed light on hitherto less explored aspects of Irish nationalism, highlighting the outward looking nature of Irish revolutionaries at a time of change.

Dr Lili Zách is a research assistant at Maynooth University. In 2016 she completed a PhD at NUI Galway entitled ‘Irish perceptions of national identities in Austria-Hungary and its small successor states, 1914-1945’.