Ireland’s Pacific World 1916–1923

By Prof. Malcolm Campbell

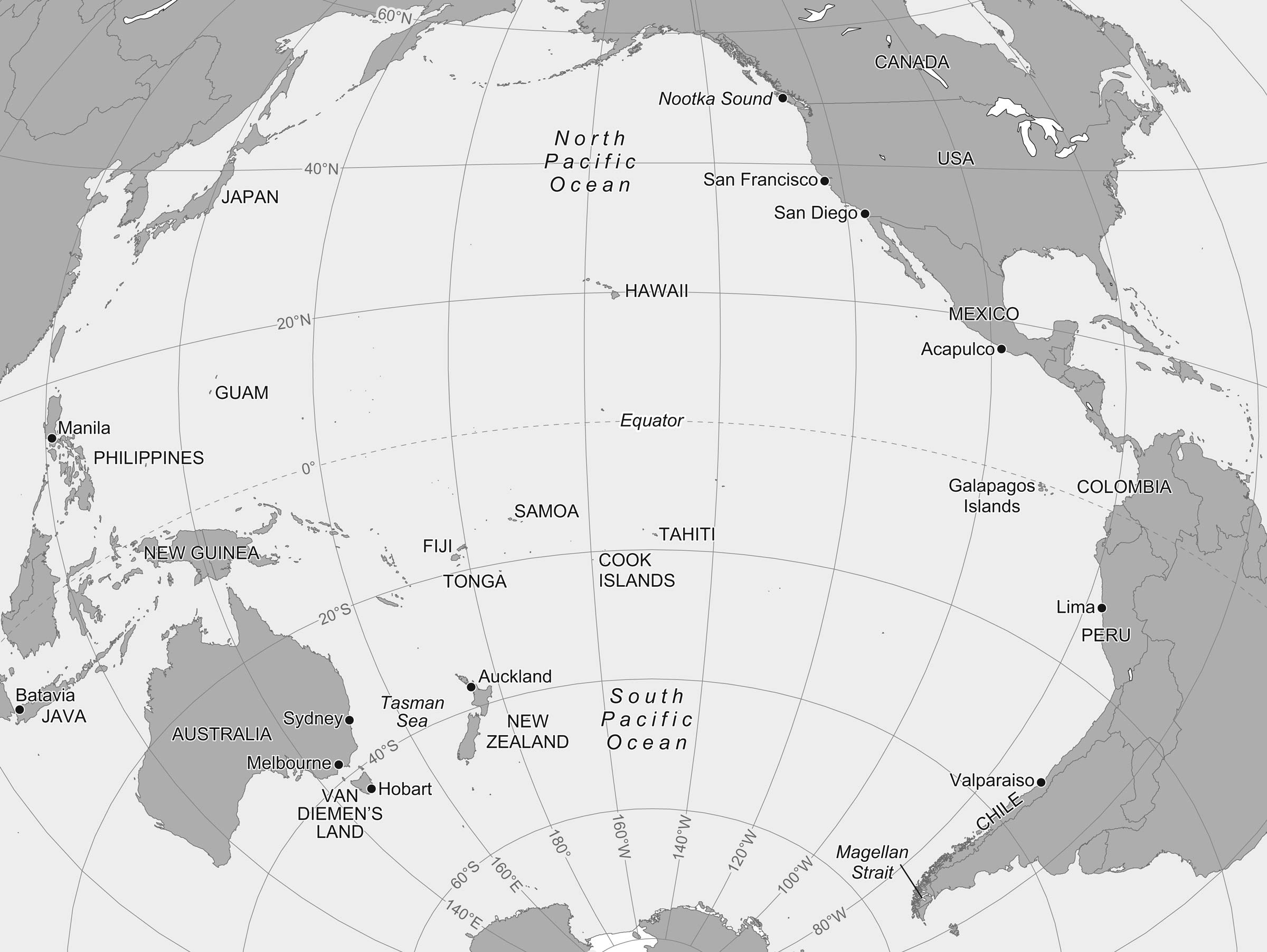

Political developments in Ireland during the period from 1916 to 1923 produced seismic tremors across the Pacific World. Most Irish communities in this oceanic space, an area extending from the West Coast of the Americas to Australasia, had shown long commitment to the Irish Parliamentary Party and the Home Rule cause. Consequently, they experienced intense confusion over the rapid reorientation of the Irish political scene after 1916. While supporters of Irish independence struggled to adapt to the new realities of Irish politics, immigrants and their descendants confronted increasingly hostile and suspicious host communities where anti-Irish sentiment and sectarianism escalated to their highest point in decades.

In 1911, more than a quarter of a million Irish men and women resided in the Pacific World. 180,000 Irish-born lived in Australia and New Zealand. 100,000 more lived on the North American West Coast. Hundreds also resided in island groups throughout the Pacific as colonial administrators, traders and missionaries. While the Irish in California fervently opposed Ireland’s participation in the Great War, throughout the British Empire strong support existed for John Redmond’s commitment that Irish troops would serve ‘wherever the firing line extends’. Sons of Home Rule families in Australia and New Zealand enlisted in 1914 and served beside Irish troops in the Dardanelles campaign in 1915.

The Easter Rising took Irish immigrants and their descendants in the Pacific World by surprise. Herbert Moran, who was born in Australia in 1885 to Irish parents, trained as a physician, and captained the Australian Rugby Union team on its first international tour of Great Britain in 1908. Moran, who later enlisted as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, wrote that the ‘new generation of Irish-Australians ardently desired to be loyal. They wished very much to escape from the bleak moorland of perpetual resentment.’ He described their reaction to news of the Easter Rising as one of ‘dismay and resentment’.

British retribution in the wake of the Dublin rising rapidly transformed Irish opinion. In New Zealand, the influential Irish labour activist Harry Holland lectured throughout the country in late 1916 and early 1917 to enthusiastic audiences, explaining the long history of English misrule and oppression in Ireland. Roman Catholic religious leaders who had initially condemned the Dublin insurgents now publicly criticised the disproportionate British reaction. Irish leaders urged the immediate implementation of Home Rule. Responding to the weight of public sentiment on the Irish issue, in March 1917, the Australian Senate passed by 29 votes to two a motion to present an address to the king expressing the hope that ‘a just measure of Home Rule may be granted to the people of Ireland.’

While Irish communities protested against the execution of the leaders of 1916, large numbers of New Zealanders and Australians also railed against what they perceived as Irish disloyalty during a time of national crisis. Sectarianism increased to levels not seen since the 1860s. Protestant political leaders targeted in particular the public pronouncements of the Bishop of Melbourne, Daniel Mannix, a Sinn Féin supporter and the most outspoken Australasian critic of British policy in Ireland.

Native ward, Tulagi Hospital c. 1918 (Charles Morris Woodford). Courtesy of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau (PMB PHOTO 58-068). Australian National University Archives: Charles Morris Woodford papers on the Solomon Islands and other Pacific countries, ANUA 481-1A.

Suspicion of Irish men and women spread throughout the Pacific World. In July 1915, a recent Irish medical graduate, Dr Joseph O’Sullivan, commenced his appointment as a medical officer at the port settlement of Tulagi in the remote Solomon Islands. O’Sullivan was one of two doctors responsible for public health throughout the British Solomon Islands. His responsibilities included the provision of care for the expatriate European population in a small, recently constructed hospital, as well as oversight of public health measures to lessen the impact of diseases including dysentery on plantation labourers through the archipelago.

While some visitors to the Solomon Islands praised young Dr O’Sullivan, events in Ireland soon intruded on his medical practice. By the second half of 1917, messages from the British administrator in the Solomon Islands, Charles Workman, condemned the Irish doctor’s political views. Workman described the physician as unfit for continuation in the colonial service. Although the acting-resident conceded that O’Sullivan had carried out his medical duties honestly, Workman criticised the colonial office for ‘the selection of officials who after two years’ service are incapable of winning the respect of either natives or Europeans’.

Bigotry and discrimination coloured new appointments to the colonial service. Early in 1918, Dr O’Sullivan returned to Sydney to recruit new nurses for the hospital at Tulagi. The Australian trading company Burns Philp received instructions from the British High Commission in Fiji to assist him in the selection process. The company took this role seriously. Its agent in Sydney sent behind-the-scenes reports on O’Sullivan’s efforts to select the new nurses. The agent, W. H. Lucas, wrote in confidence to the British High Commission in Suva that when considering applicants, ‘it soon became apparent that the only applications which interested [Dr O’Sullivan] were those bearing Irish names and with training in Catholic institutions.’ According to Lucas, O’Sullivan’s first preference for appointment was a Roman Catholic nurse, but he successfully persuaded the doctor to favour the appointment of another candidate on the grounds of her superior experience. The agent discretely reported to the High Commission that his preferred candidate ‘describes herself as Church of England, which is satisfactory.’ Lucas labelled Dr O’Sullivan’s preferred candidate for the role as ‘a very Irish type indeed’, and opposed her employment. The Burns Philp manager also felt compelled to defend his national and religious preferences to the British authorities: ‘At the present time, however, there is such a lot of disloyalty amongst the Irish Catholic section of the community, that one is merely imitating the ostrich by ignoring the fact.’

Government House, Tulagi c. 1909 (Charles Morris Woodford). Courtesy of the Pacific Manuscripts Bureau (PMB PHOTO 58-123). Australian National University Archives: Charles Morris Woodford papers on the Solomon Islands and other Pacific countries, ANUA 481-1A.

The issue of conscription heightened concerns over the loyalty of Irish newcomers. While New Zealand, Canada and the United States eventually implemented compulsory service, divisive conscription plebiscites in Australia in 1916 and 1917 split the Australian Labor Party and caused widespread public animosity. Bishop Mannix’s prominent role as an opponent of compulsory war service intensified scrutiny of the Irish population. In the Solomon Islands, Dr O’Sullivan’s personal opposition to conscription in Ireland proved to be the last straw. The administrator, Mr Workman, informed his superiors that O’Sullivan’s Irish nationalist impulses were undiminished by his time in Australia. ‘Only yesterday at my own table Dr O’Sullivan said that he was confident Irish fathers would shoot their sons rather than permit them to be conscripted.’ Terminated from the colonial service soon after, Dr O’Sullivan, his wife and daughter left the post at Tulagi and moved to Queensland.

The events of 1916 also triggered a small number of more radical Irish in Australia and New Zealand to reach across the Pacific Ocean to American republican activists. Brothers Matthew and Patrick Organ, born in Cork in 1885 and 1887 respectively, proved to be lynchpins in maintaining trans-Pacific connections during the war years. Matthew Organ was in contact with the prominent San Francisco priest Father Peter Yorke and smuggled proscribed publications and other republican propaganda into Australia and New Zealand.

The Irish Republican Brotherhood established its first Australian Circle, in Melbourne, following the Easter Rising. Led by Maurice Dalton, a veteran Fenian, and John Doran, an American citizen of Irish birth, the movement spread north along the Pacific Coast. In July 1916, two circles totalling 20 men swore loyalty to the organisation in Sydney while a Brisbane circle followed the next month.

Doran wrote to the renowned Clan na Gael leader, John Devoy, reporting on the establishment of the Australian IRB and foreshadowing a visit to the United States. In September 1916, he embarked for San Francisco, where, upon arrival, he assumed the title of ‘representative of the Australian wing.’ Doran wrote a hopeful report on his progress in consolidating the trans-Pacific connection, hinting to Australian IRB associates of future action planned in Ireland. Concerned at the actions of its small cell of militant Irishmen, the Australian Government interned seven members of Sydney’s Irish National Association. In New Zealand, Irish activists also claimed to have links with United States republicans and envisaged participating in the fight for Ireland’s future.

Despite initial optimism, the fragile connections forged in the last years of the Great War proved unsustainable and did not produce a viable Pacific-wide republican movement. With aging Irish populations on either side of the Pacific and few new immigrants arriving, the population of Irish descent focussed on consolidating their lives in their new nations rather than playing the patriot game. Divisions over the Treaty and the Civil War in Ireland contributed to an increased sense of estrangement from Irish affairs.

Despite its great distance from Ireland, the Pacific World experienced the impact of Ireland’s political transformation. In addition to the impact on the lives of contemporaries, the legacy continued for several generations as sectarian fissures continued. The experience of its Irish inhabitants and their descendants in this oceanic space constitutes a small but significant part of the history of Ireland’s global revolution.

Malcolm Campbell is head of the School of Humanities at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. Born in Australia and a long-time resident of New Zealand, he has published widely on the history of the Irish in Australasia and the Western United States.