Ireland’s Comintern Generation

By Maurice J. Casey

In March 1919, the Third International, more commonly known as the Communist International or Comintern, was founded in Moscow. An organisation dedicated to directing the activities of communists across the world, the Comintern’s ambition was nothing less than the revolutionary transformation of the globe. ‘A new era in world history has begun’, Lenin stated in an article published shortly after the Comintern was established. The Bolshevik leader described the Comintern as an organisation of ‘epoch-making significance’ one which would direct ‘the movement of the proletariat for the overthrow of the yoke of capital’. Part bureaucratic apparatus and part radical networking opportunity, the Comintern shaped the experiences of thousands of activists during the interwar period. Among those whose lives were impacted by its revolutionary designs were many Irish men and women.

The lives of the individual activists who moved through the labyrinthine networks of international communism make for fascinating case studies. While Ireland’s communists were always small in number, the existence of the Comintern ensured that they had the backing of a well-resourced organisation. Beyond its funding and direction, the Comintern fostered a social world of transnational radicalism wherein activists could meet their counterparts at international congresses and experience Soviet socialism first-hand through visits to the USSR. These experiences shaped radicals in curious ways, forming a global generation of activists unlike any other seen before or since. This was a movement which inspired devotion in celebrated revolutionaries such as Georgi Dmitrov, the Bulgarian communist who famously defended himself in court against Nazi accusers, and Tina Modotti, the prominent Italian photographer who honed her craft while simultaneously working as an underground Comintern activist – to take but two well-known examples. Adopting a biographical approach and peering into Irish radical lives allows us to trace the resonances of what could be termed Ireland’s ‘Comintern generation’.

From the outset, Lenin and the Bolsheviks realised that the revolutionary torch lit in Petrograd in 1917 was in a vulnerable position. Conditions in Russia at the end of the Great War were not conducive to the building of a socialist paradise, with famine and civil war erupting throughout the country. There was, nonetheless, reason to believe that from the Bolshevik spark the fire of world revolution would flare up. Insurrectionary forces emerging from the cataclysm of the First World War, spearheaded in Ireland with the Easter Rising of 1916, suggested a worldwide wave of revolt against the status quo. The Bolsheviks initially believed that if the workers in powerful nations such as Britain and Germany took control, then proletarian solidarity would send these workers to the rescue of their blockaded and industrially underdeveloped Russian comrades. The Comintern was designed to inspire and direct these international proletarian forces, advocating their adoption of models deployed by the Bolsheviks such as workers councils’ and proletarian dictatorship as pathways to revolutionary transformation. Leon Trotsky, in a stirring address to the Comintern’s founding congress, called for the workers of the world to unite under the banner of ‘workers’ councils and the revolutionary struggle for power and the dictatorship of the proleariat’.

Ireland, as Marx and Engels themselves had suggested, could also play a role in revolutionary transformation. The Comintern believed, as Emmet O’Connor notes in his history of Irish-Comintern interactions Reds and the Green, that Ireland was ‘a colony with an uncompleted national question’. The communist solution to this lasting question was, naturally, revolution. Comintern interventions on Irish issues during Ireland’s revolutionary period and after were focused on realising its anti-imperialist potential.

But to make meaningful contact with the Comintern in an era before mass communication, Irish revolutionaries needed to reach the cities of Petrograd and Moscow where the organisation’s world congresses were being held. This was no simple task in a world where the ruins of a war sluggishly coming to an end still scarred the European landscape. Soviet Russia was blockaded by Allied forces, rendering the eastward land route impassable. The Northern Underground, a network in operation since the late nineteenth century that connected Russian revolutionaries to the west via Scandinavian comrades, was re-energised to help radicals breach the cordon sanitaire established to prevent the Bolshevik contagion from spreading. This underground railroad for radicals transported rebels such as the American journalist John Reed and Roddy Connolly, the son of James Connolly, to the crucible of the world revolution. Roddy Connolly’s political career, charted in detail by his biographer Charlie McGuire, took him from marching into the GPO on Easter Monday in 1916 to involvement with the Irish Labour Party in the decades before his death in 1980. Ireland’s revolutionary period would provide this scion of the great Irish socialist with his formative political experiences.

The IIIrd Communist International at Smolny Institute, Petrograd in July 1920. The left banner reads "FSSRR" and the right banner reads (in French): 'Fraternal greetings to the IInd Congress of the IIIrd Communist International'. (Image: The Graduate Institute Geneva)

The tale of how Roddy Connolly made his way to the Second Congress of the Comintern in 1920 remains one of the most intrepid journeys in the history of the Irish left. Connolly and his travelling companion, Belfast-born Eadhmonn MacAlpine, began the journey as stowaways in a ship departing from Hull, travelled through Scandinavian ports to Murmansk and then finally made their way to Petrograd. Along the route, the duo survived a near-fatal storm at sea and an aerial attack from a British plane. These two Irish delegates at the World Congress were able to mingle among the world revolutionary elite, including Lenin himself, and discuss the prospects for revolution in Ireland.

So began the first Irish movements through the networks of the Comintern. Connolly and MacAlpine blazed a trail to the Comintern that other radicals connected with Ireland would soon follow. Some are well-documented, such as Connolly and ‘Big Jim’ Larkin, the towering figure of the 1913 lockout whom the Comintern misguidedly hoped would bring the Irish masses toward communism. Other more obscure Irish ‘Cominternians’ have walk-on roles in the memoirs and recollections of other international communists. In the summer of 1921, for example, Evgeniia Bouvier, a former Lewisham suffragette turned communist, recognised a couple seated at Petrograd’s monument to Catherine the Great, sharing an issue of a British communist newspaper. The familiar pair were Sidney Arnold, a Latvian member of the Socialist Party of Ireland, and his Irish wife Rosa, who had both come to the city to work at the Comintern’s Third World Congress. They would not be the last to make the journey from Ireland to Russia to work for the Comintern.

The flow of reports and revolutionaries through Comintern networks was eased once the waves of post-armistice violence across Europe receded and the Bolsheviks emerged victorious from the Russian Civil War. In the early 1920s, the Comintern constructed an efficient information gathering machine supported by a courier network. Comintern activists were trained in the clandestine transport of reports and radicals. No political initiative was too fleeting or picaresque to merit archiving by the Comintern. The documents filed by the Comintern, now permanently preserved in the archives in Moscow, include a copy of the Democratic Programme of the First Daíl in 1919 and rare original material produced by Irish leftist initiatives of the 1930s such as Saor Éire and the Republican Congress.

But some of the most intriguing Irish material in the Moscow archives is held in the lichnye dela, or personnel files. Maintained by the cadre commission of the Comintern, which oversaw the foot-soldiers of the world revolution, these files contain a range of material, including biographical statements produced by communists, questionnaires completed upon arrival in Moscow and letters of recommendation. The Comintern maintained seventy-seven individual files in its Ireland folder. Other Irish radical lives can be unearthed in the folders belonging to Communist Parties operating in major sites of Irish emigration, such as Britain, Australia and the United States. These documents provide insights into the lives of obscure Irish activists, translators and students who interacted with the Comintern.

Take, for example, the details recounted in the Comintern personnel file maintained on Cork-born radical Michael Delurey, who attended a revolutionary school in Moscow under the name “John Snail”. Delurey’s 1933 autobiographical statement demonstrates how an Irish radical life could be played out on a global stage, mixing together nationalist and internationalist commitments in a potent political cocktail. Delurey was educated by the Christian Brothers in Cork, joined and then deserted the British Navy, travelled to the US stoking ship engines, took part in strike action with the Industrial Workers of the World in New York and then spent eight months gun-running for the IRA in 1922. He was radicalised on the decks, reading leftist newspapers alongside the work of James Connolly and Tom Paine while travelling from port to port. Described by the Party as a ‘theoretically raw comrade’, Delurey admitted that he had read little of Marx or Engels before his induction into the Communist Party of Ireland. He also listed, in his statement to the Comintern, stints in military prisons and a ship’s brig – which he escaped while being brought ashore for new clothes. Incarceration demonstrated revolutionary mettle and was frequently highlighted in communist autobiographies. Delurey’s life indicates the global paths of travel that Irish activists navigated in their journey towards the world revolution. Without the obsessive information gathering impetus of the Comintern, Delurey’s story, one among thousands of remarkable working-class autobiographies now held in the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History, would likely be lost to history.

The wide net that the Comintern cast in search of material has been useful for historians plumbing the Comintern archives for sources, but the creation of this rich paper trail also provided Comintern representatives, most of whom had never stepped foot on Irish soil, with an often impressive level of insight. One intriguing indicator of this is a letter dispatched from the Comintern to the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1932, which directed the Party to send its newspaper the Daily Worker to the Irish Free State – but with all reference to birth control removed. Organising in distant Moscow, the Comintern was nonetheless aware of the priestly-influenced censorial streak in the Irish Free State.

Operating under the shadow of a fortified Catholic Church in the Irish Free State, many communist-inspired initiatives were subject to resistance, such as when, in 1933, the home of Charlotte Despard, the Anglo-Irish suffrage veteran and Communist convert, was attacked after she established a 'Workers’ College' on the premises. In Northern Ireland, prospects of revolution fared little better, despite the communist-directed and cross-community militancy that took place in Belfast in 1932: the Outdoor Relief Strikes. From behind the street barricades emerged a leading figure in Irish Communism, and one of the relatively small number of women whose loyalty the Party commanded. Betty Sinclair, born into a working-class Protestant family, was dispatched to Moscow in January 1934 for further instruction in Bolshevik theory and practice after assisting in the Belfast strikes. Sinclair would remain a dedicated Party member until her death in 1981.

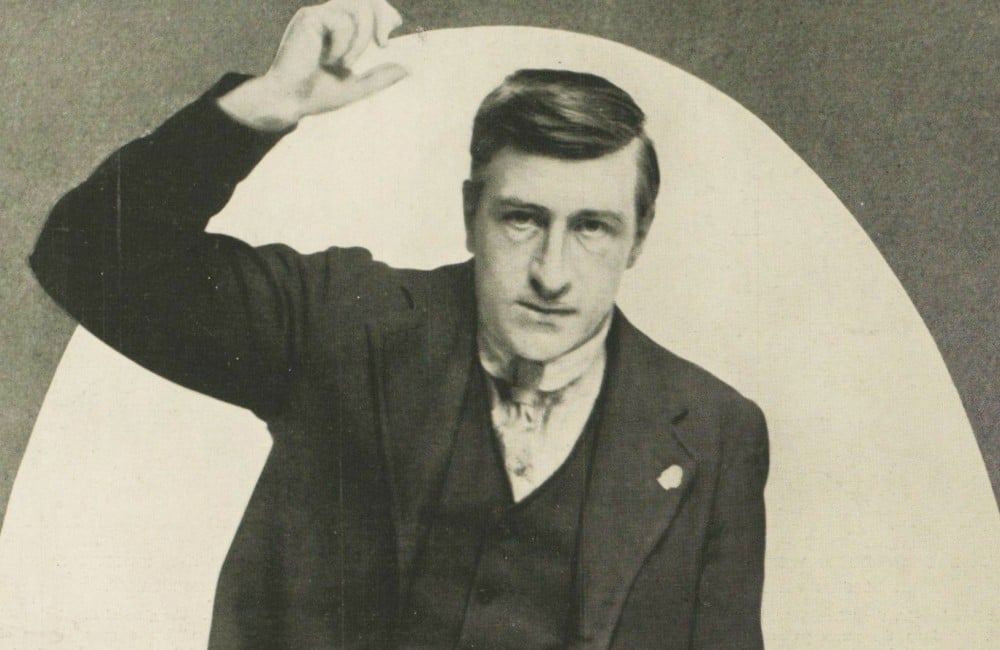

Jim Larkin. (Image: Illustrated London News, [London, England], 22 Nov 1913)

But the Comintern was unable to retain the loyalty of every Irish revolutionary who navigated its networks. Several Irish radicals previously attached to the Comintern’s tenets broke with the organisation – most famously the intemperate Jim Larkin. Another interesting example is Tom O’Flaherty, brother of the novelist Liam O’Flaherty. Tom, also a talented wordsmith, was an early member of the Communist Party of the USA and journalist for the Party press. Following factional fighting in the late 1920s, Tom ultimately aligned with a Trotskyist split from the Comintern-backed Party. In a 1933 letter to a comrade, sent from the O’Flaherty homestead on Inis Mór, Tom referred to his fellow radicals as ‘horseshit artists’ and declared that the Comintern was ‘as dead as Saint Anne’s shinbone’. The impassioned language of his peasant ancestors still pulsed through his veins.

Others, however, found themselves unable to break free from the Comintern - with tragic consequences. Three Irish radicals whose names can be found among the files maintained by the Comintern; Padraig Breslin, Brian Goold Verschoyle and Sean McAteer, witnessed the darkest side of the Soviet dream. Breslin and McAteer were both political emigres in the USSR who found themselves swept up in the Stalinist purges. Goold-Verschoyle, meanwhile, was kidnapped by the Stalinist secret police in civil-war wracked Spain. As Barry McLoughlin charts in his collective biography of these three men Left to the Wolves, none would live to see Ireland again after their personal encounters with the brutality of the Stalinist regime.

In 1943, the Comintern was dissolved by Stalin as a concession to the USSR’s allies in the fight against Nazi Germany. It had not achieved its aim of world revolution, but it did mould a political generation. Just as the Irish revolutionary period still retains potency a century after its events took place, so too do the aftershocks of the Comintern continue to resonate in Ireland and abroad. In the late 1960s, for example, the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association rose to prominence. One of its founding figures was a member of Ireland’s Comintern generation: Belfast’s own Betty Sinclair, alumni of the International Lenin School in Moscow. This is not to suggest that civil rights demands were a communist conspiracy hatched in Moscow, but rather that the ties that bind together political generations are always multiple and complex. The seemingly distant world of global revolt that influenced the Irish revolutionary period continues to shape our own.

Maurice J. Casey is a doctoral candidate at Jesus College, University of Oxford. His current research explores the international connections of Irish radical women during the interwar period.