Ireland and the assassination culture of imperial Britain

By Prof. Simon Ball

In 1909, the then Liberal Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, laid out what became, for the next seven decades, the British imperial state’s standard response to assassination conspiracies. He observed that ‘character and methods’ of such conspiracies were ‘happily confined to a small number of people’. Nevertheless, the conspirators would be ‘desperate and determined’ in their methods. Asquith’s formulation could be broken down into three parts. First, that there would be organised assassination conspiracies that threatened the British state. Second, that very few people would be involved in those conspiracies. Third, that the conspiracies would be dangerous because of the violence of their methods, not because they represented the tip of an iceberg. The implication of Asquith’s analysis was that assassination was an inevitable cost of being an imperial power. Assassinations themselves would not threaten the stability of the empire. What was important was how the state dealt with these unavoidable events. There was little point in becoming too emotional about losing imperial officials: overreaction was best avoided since it vested the procurers of assassination with a legitimacy not warranted by their popular support. This was the so-called ‘liberal script’ for dealing with assassination.

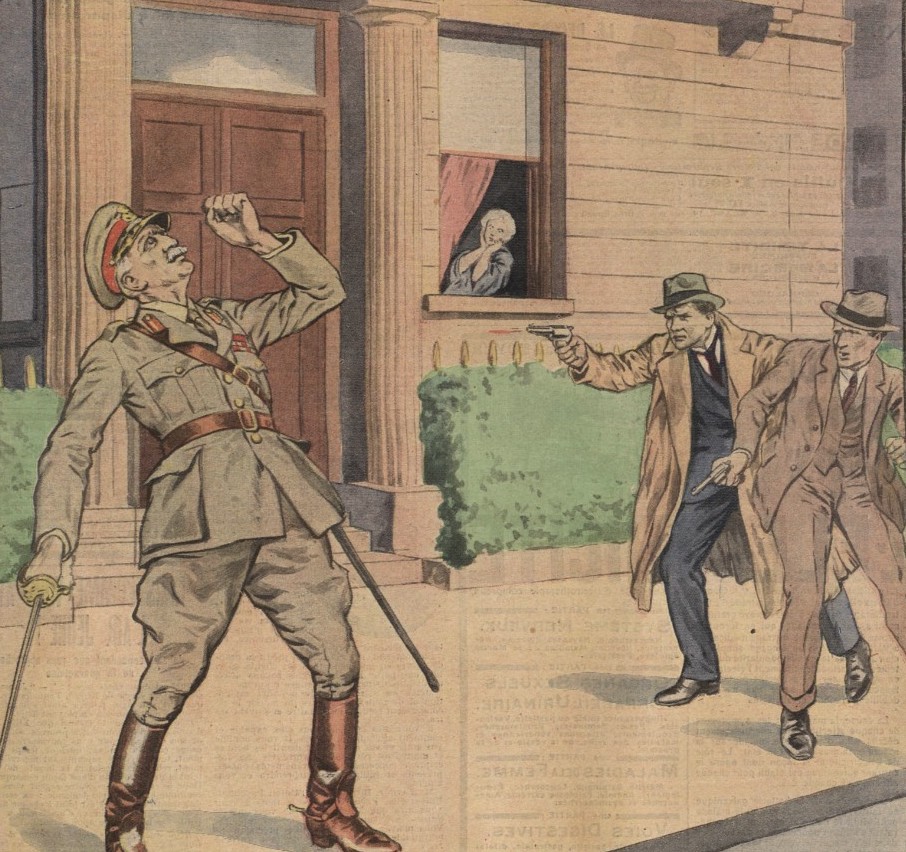

Asquith was most definitely not talking about Ireland. The immediate occasion for his remarks were the assassinations carried out by Hindu extremists in both India and Britain. In 1909, an engineering student at University College, London, had assassinated Sir Curzon Wyllie, an influential civil servant in the India as he left a meeting at the Imperial Institute in London. The same group had then assassinated a senior civil service officer, the collector of Nasik, as he attended the theatre in Bombay. The wider context that shaped Asquith’s thoughts was the emergence of a new type of assassination at the beginning of the twentieth century. Most often linked with Anarchists, modern assassination used the latest technology, the small calibre repeating pistol and high explosives. The ‘oriental’ assassinations of the Victorian era had been carried out, according to the Edwardian world view, by primitive people using primitive methods, most notable the ‘assassin’s dagger’. The last major assassination associated with Ireland had been both long in the past and carried through by such methods. Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Burke had been stabbed to death in Phoenix Park in 1882.

In adopting modern methods in 1919-20 militant Irish republicans were catching up with global best terrorism practice, of a kind the British empire had observed for a decade. In 1919 Michael Collins, as IRA Director of Intelligence and President of the IRB, organized ‘The Squad’ under his direct command to carry out assassinations. The Squad itself was a very small cadre, and it was frequently reinforced by other IRA men. The most high-profile intended victim was the Viceroy, Field Marshal Lord French. At the end of 1919, French was ambushed by two dozen assassins as he drove from the railway station to the Viceregal Lodge in Dublin. Four shots hit his car, wounding a policeman. French’s military escort shot and killed one of the assassins who was armed with a Smith & Wesson revolver, a semi-automatic pistol and a hand grenade. Such equipment had become the hallmark of ‘global best terrorism practice’. In 1917 a British ministerial committee that investigated the issue had concluded that the ready availability of such weapons after the Great War would constitute a dangerous threat to the British empire. Notoriously, Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated using a semi-automatic pistol in Sarajevo in 1914, sparking the outbreak of the Great War. The same brand of pistol had been used in India.

Collins’ assassins continued to pick off imperial officials. In March 1920, for instance, the magistrate Alan Bell, who was investigating the attack on French, and IRA funding, was taken in daylight from a Ballsbridge tram and shot, without anyone interfering. ‘The Squad’s’ most notorious exploit, however, was the ‘systematic assassination’ of the so-called ‘Cairo Gang’, supposedly a specially recruited and trained group of army intelligence officers. In all a dozen officers were assassinated on Bloody Sunday, 21 November 1920. In all, nineteen people were shot by ‘The Squad’. As Collins acknowledged, there was more guesswork involved in the assassinations than the IRA would admit in public. ‘We had no evidence’ that some of the officers were ‘Secret Service Agents’, Collins noted. Some of the assassinated were ‘just regular officers’ whose name had been added to the death list by IRA men with a grudge. The British army’s analysis of the incident, written in 1922, concluded that the assassinations had dealt military intelligence a serious blow:

the murders of the 21st November, 1920, temporarily paralyzed the special branch [of Dublin military district]. Several of its most efficient members were murdered and the majority of others resident in the city were brought into the Castle and Central Hotel for safety. This centralization in the most inconvenient places possible greatly decreased the opportunities for obtaining information and for re-establishing anything in the nature of secret service.

However, as Collins further observed, ‘England could always reinforce her Army. She could replace every soldier she lost’: the assassinations only had a short-term effect. Military intelligence was rebuilt. Within a few months, more effective British counter-intelligence had forced the IRA to rely on large-scale terror rather than targeted assassination.

Notoriously, the British army did not, in the immediate aftermath of the murders, follow the Asquithian protocols: it shot a number of people who had nothing to do with the assassinations in Croke Park later on the same day. However, in London the response was more measured. This was best illustrated by how the government dealt with assassination in mainland Britain. Acknowledging that Ireland was more trouble than it was worth it negotiated with Collins, finally signing an Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. The former chief of the imperial general staff, and current Ulster politician, Henry Wilson, fulminated that that British policy on Ireland was dictated by a ‘Cabinet … running away from Valera’s pistol’. He quoted Marshal Foch with grim satisfaction: ‘You cower under the assassin’. The essential untruth of that statement was illustrated when, in June 1922, an unguarded Wilson was himself assassinated in London. In dealing with the aftermath of Wilson’s assassination, the cabinet specifically referred to the procedure that Asquith had developed for the Wyllie murder as its ‘precedent’.

There were certainly voices raised in parliament, and outdoors, who wished to portray the assassination as evidence that the whole ‘Irish race’ was addicted to assassination. Winston Churchill, speaking for the government, on the other hand, argued that ‘the Irish people had clearly shown their support of the Treaty’ and that the assassination was the work of a ‘rebellious faction’. The Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police told ministers that he had ‘complete liaison’ with the Irish provisional government and had ‘been in close communication with Mr Michael Collins’. The British and Irish governments agreed that the assassins were ‘Rory O’Connor Republicans’ and that the British would deny the Four Courts rebel the oxygen of publicity. The gunmen themselves were in custody, and there was ‘general agreement … to bring the prisoners to trial and to convict them as soon as possible; to avoid anything which would give the appearance of a great political trial’. The murderers were rapidly tried and executed. The Provisional Government entered a half-hearted protest and little more was said about the matter in Britain. The ‘liberal script’ had been followed to the letter.

It was not on account of Ireland that Britain re-assessed but then re-asserted its Asquithian assassination culture. Rather that re-assessment took place on account of Egypt. Like Ireland, Egypt became a ‘free state’ in 1922, formally independent but still hog-tied into the empire. Modern assassination had been an endemic feature of Egyptian political culture since 1910. In 1924, Sir Lee Stack, commander-in-chief of the Egyptian army and governor general of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan was assassinated by a conspiracy working in cahoots with the Egyptian government. The British high commissioner in Cairo, Lord Allenby took the kind of steps that Lord French would never have been allowed to contemplate in Ireland. By chance the former prime minister, Asquith, was Allenby’s guest in Egypt, although that did little to stay his former general’s hand. Allenby directly accused the Egyptian government of complicity in the murder. He overthrew that government by the threat of military installed. He installed a government favourable to British interests. British troops held provocative parades in Egypt’s major cities to underline the point that the Egyptian populace was powerless in face of Britain’s military power. RAF aircraft overflew the countryside to make the same point about aerial power.

Most importantly, Allenby engineered a significant geopolitical transformation of the region. He unilaterally ended Egypt’s role in the condominium over the Sudan. Sudan thus became a British colony, and ultimately a candidate for independence as an independent nation.

Notably, however, the British government took steps to limit Allenby’s actions. In the very short term there was little London could do to rein in the ‘liberator of Jerusalem’. It rapidly dispatched diplomats to arrange an accommodation with Egyptian nationalism more in line with that reached with the Irish Provisional Government. The assassins were declared part of, as it were, a ‘rebellious faction’, thus avoiding the need to condemn the whole political nationalist movement. The limited number of politicians put on trial were acquitted. It was the assassins themselves who were convicted and executed, bringing the matter to as rapid an end as the British government could engineer after Allenby’s term of office expired. The Asquithian norms had been re-asserted.

The British government had identified the threat posed by ‘desperate and determined men’, armed with modern weapons, and bent on murder, long before Michael Collins adopted such methods in Ireland. The belief that assassination was an inevitable part of the imperial experience accounts in part for what seemed to later commentators the casual security procedures adopted by British officers in Ireland. What Collins achieved was a more concentrated application of violence than had been possible in most parts of the empire. In this, he more resembled European terrorists, such as those active in contemporary Germany, than a colonial rebel. In the few hours after Bloody Sunday began, some British personnel in Ireland went off script and gifted republicans a propaganda boost. The ‘liberal script’ was rapidly restored by London. That ‘liberal script’ continued to endure until such time as Britain could no longer respond to assassination by capturing and executing the assassins. The last death sentence for an assassination in the British empire was passed in 1973: two years later the Provisional IRA launched its campaign of ‘high value’ assassination on the British mainland. By then the British empire was no more, and British political culture could draw few lessons from its experiences earlier in the century.

Simon Ball is Professor of International History and Politics at the University at the University of Leeds. His book Secret History: Writing the Rise of Britain’s Intelligence Services from the Great War to the Cold War will be published early in 2020.