Global Lives: Tom Glynn

By Dr John Cunningham

Galway-born Tom Glynn was a prominent labour activist, ideologue and journalist in South Africa and Australia, initially advocating an American variant of syndicalism and, for a time, Soviet communism. He is best remembered as one of the ‘Sydney Twelve’, imprisoned in 1916 for their pugnacious part in Australia’s anti-conscription movement. As a peripatetic radical, like James Connolly and James Larkin, Glynn was a characteristic labour figure of his era. With approximately six million emigrating in the period between the Famine and the First World War, the Irish contribution to early labour movements was made more often in cities and mines of the Anglophone world outside Ireland than in Ireland itself. Along with such contemporaries as Cork-born Mother Jones in the United States, Wexford-born Mary Fitzgerald in South Africa, and Youghal-born Tom Walsh in Australia, Tom Glynn was one of the pioneers in this regard.

Glynn was born in 1881, the third child of a shepherd of Gurteen, Co. Galway, a hot spot of the developing land war. When he was 2, his mother died from gynaecological complications in pregnancy. At 17 he travelled with his older brother Paddy to Melbourne, where three of his father’s siblings had settled. A city of half-a-million people in 1898, Melbourne was considered to be more cosmopolitan than the similarly-sized Sydney, its people more aloof and self-assured, and its appearance more imposing. Tom Glynn’s arrival was at an unpropitious time however, when economic adversity coincided with disruption in his Australian family circle. With few options, he entered the service of the empire that he would spend most of his adult life opposing.

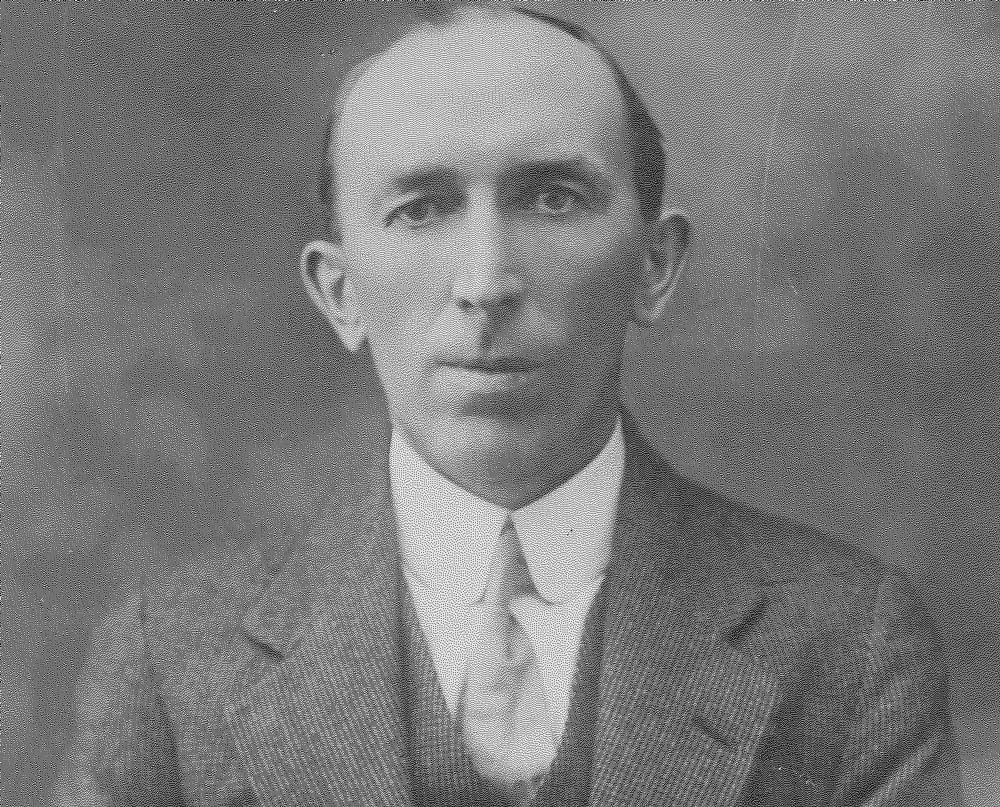

Photograph taken on the release of ten of the Sydney Twelve in 1920. Tom Glynn is on second row, left, with his daughter Molly on his knee. Peter Larkin is on the third row, beside Ann Larkin and their son. (Courtesy of Verity Burgmann)

In February 1900, following competitive public demonstrations of equestrian and firearms skills, he was accepted into the 3rd Victoria Bushmen, one of several ‘Bushmen’ units raised to combat Boer guerrilla-ism in the war of 1899-1902. If he was not dissuaded by opposition in the Irish Catholic community to Australian involvement in the conflict, evidently his experience of fighting did not change his mind either, for he re-enlisted after the disbandment of the Bushmen. He was one of an estimated 28,000 Irishmen fighting on the British side, greatly outnumbering the few hundred in two pro-Boer Irish brigades led by John McBride and Melburnian Arthur Lynch. At war’s end he entered the Transvaal police, and invited his brother Paddy to come from Australia to join that force also.

Political activist in Johannesburg

The roots of Tom Glynn’s indignant radicalism lay in

conflicts with police superiors, including censure faced for

refusing an order to shoot an African. Then, on the reorganisation

of the police around 1907, he and his brother retired with service

gratuities. Both found work alongside other ex-servicemen on

Johannesburg’s municipal electric tramway. For his political

activism, the earliest evidence is from Archie Crawford who in

1911 recorded his first encounter with Glynn:

About two years ago a tall slim fellow of modest but retiring disposition, wearing a motorman’s uniform, would sit in some obscure corner of the Socialist Hall. Only when some ‘faker’ would propound a fallacy calculated to miseducate and mislead the working class would he stir… forcibly and with lighting rapidity express himself, astonish everyone… just as suddenly sit down. Here I thought is a rebel if ever I saw one.

From attending meetings, Glynn was drawn into a political milieu dominated by Crawford and his lover, Irishwoman Mary Fitzgerald, whose fiery militancy would earn her the sobriquet ‘Pickhandle Mary’. Labour bodies in Johannesburg were dominated by English and Scottish men, and the emergence of Glynn and Fitzgerald, ‘a son and daughter of the Emerald Isle’, as ‘chief characters… of the class struggle’ there was remarkable enough as to attract comment. However, given that both were already integrated through their military service into the community of uitlanders (English-speaking incomers to the Transvaal), there were no particular barriers to their involvement in public affairs. First contributing to Crawford and Fitzgerald’s weekly Voice of Labour, Glynn acted as its editor when the former temporarily left Johannesburg. Polemical from the beginning, and often engaging with economics, his writings became increasingly syndicalist in their thrust.

Syndicalism was an anti-capitalist and self-consciously internationalist ideology widespread prior to the Russian revolution, James Larkin’s ITGWU being its Irish manifestation. Influenced by Marxism and anarchism, its salient features were hostility to existing trade unions, denounced for their elitism and acquiescence, and a distrust in the capacity of politics to bring about change. Some syndicalists, like Glynn, utterly rejected parliamentary politics; others, including James Connolly, saw benefits in the political organisation of Labour. For syndicalists generally revolutionary change would be achieved by the organisation of all workers in an industry – regardless of skill, sex or ethnicity – into militant industrial unions.

Johannesburg tramway strike committee, January 1911. Tom Glynn is at centre (under 58). Paddy Glynn was a member of the strike committee, but cannot be identified here.

Quite how he fell under syndicalism’s spell is unknown. There were certainly syndicalists in his political circle, while syndicalist material circulated in Johannesburg in American publications like the International Socialist Review. By 1911, in any case, he was aligned with the ‘revolutionary industrial unionists’ of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose founders in 1905 in Chicago included Mother Jones, and the Irish-American Fr Tom Hagerty. And he had a vehicle for his ideas in the small Industrial Workers Union (IWU), of which he became general secretary. When a strike broke out in January 1911 in his own workplace, he was pushed into leadership, and quickly enrolled the entire body of tramway workers in the IWU. Surprised by the unexpected turn of events, the company conceded. The success boosted both Glynn’s status and his confidence in industrial unionism.

Confidence begot complacency, however, and when the tramway company deliberately provoked a second strike in May 1911, Glynn and his IWU were unprepared. The outcome was defeat, dismissal, and a term of imprisonment for Glynn. Unemployed and deprived of political influence, he left for North America in November 1911, visiting family in Gurteen en route, but leaving his wife and two children behind in Johannesburg.

American interlude

Glynn’s arrival in New York in January 1912 was noted in the

International Socialist Review: ‘Comrade Glenn (sic) has

never been found far from the line of battle in any time of

trouble… We hope America will be able to keep him’.

This was at a high point of IWW influence, the period of the

‘Bread and Roses’ strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

Whether Glynn visited Lawrence is not known, but he did address a

meeting in New York, before ‘riding the rods’ on

freight trains all the way to San Francisco, for a time in the

company of one of the IWW’s most militant organisers, Frank

Little. Travelling north to British Columbia, he found

agricultural work before embarking on the Sydney-bound

Makura, working his 16 day passage in the vessel’s

coal bunker.

Direct Actionist

Arriving in Sydney on 28 September 1912 – ‘Ulster

Day’ in Ireland – Glynn was immediately thrust into

political activity. On the night after his arrival, he attended a

debate organised by the Australian Socialist Party (ASP), where he

was introduced as ‘Comrade Tom Glynn of Johannesburg Tramway

Strike fame’, and invited to speak. Two weeks later,

speaking at an ASP meeting on ‘The Politics of Militant

Unionism’, he sharply criticised the brand of socialist

politics upheld by his hosts. At that point it seems he fully

intended to return to his family in Johannesburg.

Joining the Sydney local of the IWW, however, he was quickly involved in factional conflict. For Glynn the Australian body lacked a combative edge, having accommodated itself to the prevailing political culture. His faction and his perspective was soon in control, and began actively recruiting by means of impromptu street meetings in the American fashion, and at Sunday afternoon gatherings on the Sydney Domain. There was a rapid growth in membership. At the Australian convention of the IWW in Melbourne in 1913, at which Glynn was one of two delegates from New South Wales, the Sydney group took full control.

Its increased membership enabled the IWW in Sydney to publish a regular paper –a vital indicator of political purpose at that time – and the first issue of Direct Action appeared in January 1914 with Glynn as editor. He would alternate in that role with his good friend Tom Barker until his imprisonment in 1916. The title identified the Australian body with the most militant section of the Chicago-line IWW, ‘direct action’ being, in part, code for sabotage, proposed as a tactic in labour struggle by some in America, but regarded as dangerously provocative by others. For Tom Glynn, its most consistent proponent in Australia, sabotage meant ‘striking on the job’ – i.e. implementing a ‘go slow’ rather than losing wages in a conventional strike.

Direct Action was still finding its feet when war broke out in August 1914. The war gave it a campaigning focus and an expanding readership. For the left generally, the war was detrimental to workers who, it was argued, had more in common with their fellows in other countries than with their capitalist exploiters. Given the upsurge of popular patriotism however, most opponents of the war were initially circumspect in expressing their opposition. But not Tom Glynn, who immediately published a striking front page cartoon, contrasting the awful impact of war on a worker’s family with the windfall profits it brought to ‘Robberfellas’ and ‘Rothchildes’. After Gallipoli, anti-war arguments had greater currency, reflected in sales of the paper, and in attendance at Domain meetings. A policeman complained about the proliferation of the IWW’s anti-war posters: ‘Everyone I saw I defaced … and the nights following I did so I found other posters of the same kind had been posted up in their place.’ The policeman’s frustration was shared by government ministers who believed that IWW activity was a major source of demoralisation on the home front.

1916 and Ireland

Having left Ireland at 17, Tom Glynn did not often comment in any

detail on developments there. And it was hardly necessary for him

to do so after the arrival in Sydney of Peter Larkin in 1915, and

his appointment as an IWW organiser. The brother of James Larkin,

and himself a veteran of the Dublin lockout of 1913-14, Peter was

in demand as speaker, particularly following the 1916 Rising. For

his part, Glynn was struck by the labour participation in the

Rising, attributing it to the ‘desperation of a hungry,

outraged and exploited proletariat’ in the aftermath of the

lockout. But he expressed disapproval of workers’ leaders

like James Connolly – previously an IWW organiser in America

– for joining in a military endeavour alongside people who

did not share their social objectives. ‘By industrial

unionism alone’, he wrote, ‘can the armed forces of

capitalism be paralysed… can the working class of all

countries, including Ireland, be really free.’ When news of

Connolly’s execution reached him, Glynn reacted angrily,

comparing it to imperial outrages that he had witnessed against

Zulu warriors in Natal. Returning to Connolly some weeks later, he

reviewed a new Australian edition of his pamphlet

The Axe to the Root. Complimenting the analytical

approach of the executed man, he was careful nonetheless to

highlight the difference between Connolly’s conclusions and

Direct Action’s non-political approach to

industrial unionism.

Conscription, suppression and jail

By July 1916, the conflict between the Australian government and

the anti-war movement was coming to a head. Prime Minister Billy

Hughes was determined to impose military conscription, but he was

obliged to seek approval in a plebiscite/referendum. The great

mobilisation in opposition to conscription that ensued extended

beyond syndicalist, socialist, pacifist and feminist groups to

elements that had not actively opposed Australian involvement in

the war itself – most of the Labor Party, and Irish

Catholics alienated by Britain’s response to the 1916

Rising. Suspending their criticism of others on the left, Glynn

and his ‘fellow workers’ of the IWW joined

enthusiastically in the broader movement.

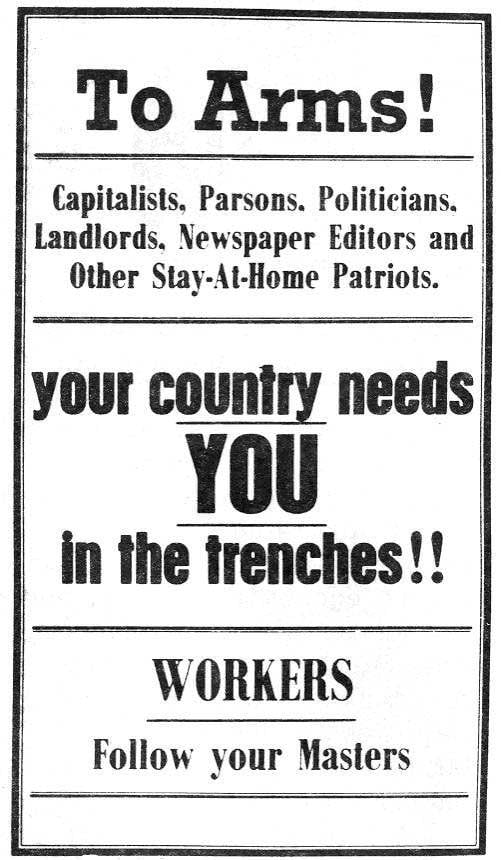

'Your Country Needs You'. Ironic IWW anti-recruitment poster from 1915, for the publications of which Tom Barker served a term in prison.

To discredit the anti-conscriptionist cause, the government and the pro-war media painted it as unrepresentative and ultra-radical. The role of the IWW was exaggerated, concurrently with a determined effort to destroy that organisation in the lead up to polling day. Glynn and other leaders were arrested, and evidence was manufactured associating the so-called ‘Sydney Twelve’ with a number of destructive fires in the city. The IWW’s advocacy of sabotage gave the accusations credibility. Much was made by the prosecution of a speech by Peter Larkin, in which he mentioned the Irish Rising and allegedly threatened to bring similar ‘ravages’ to Australia: ‘It will be far better to see Sydney melted to the ground than to see the men of Sydney taken away to be butchered’ under conscription. Convicted of conspiracy and arson, Glynn and most of the others got 15 year sentences. In the aftermath of the trial, Direct Action was shut down by the authorities, and the IWW itself proscribed. Conscription, however, was narrowly rejected by the electorate, and would be again in 1917.

The energy of the remnants of the IWW were directed at securing the release of the Sydney Twelve, and at providing for dependents – including Glynn’s second wife and daughter. At the end of the war, Alicia Glynn’s letters indicate optimism that her husband would soon be freed, but, though key evidence had by then been discredited, the Australian establishment was not disposed to forgive. It was not until August 1920, when two Independent MPs made their support for a minority Labor government in New South Wales conditional upon the re-opening of their cases that the Twelve walked free.

Glynn and the others emerged into a very different political world. Having faced severe repression in America as well as in Australia, the IWW seemed a busted flush, but the Russian revolution of 1917 suggested another way forward.

Communist

The Communist International (Comintern), founded in Moscow in 1919

to coordinate revolutionary socialist endeavour throughout the

world, paid particular attention to the IWW because of its

combative reputation. Within weeks of his release Tom Glynn was a

convert, contributing the Foreword for Comintern president Grigory

Zinoviev’s

To the I.W.W.: A Special Message from the Communist

International, published in Melbourne in September 1920. One of 16 present at

the foundation meeting of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA)

in the following month, he was elected editor of the periodical,

The Australian Communist, which commenced publication in

December. Peter Larkin was another early member of the party, as

was Irishman Tom Walsh and his wife, Adela Pankhurst, whom Glynn

had earlier encountered in the anti-war movement. Glynn’s

editorship of The Australian Communist coincided with the

high point of the Irish War of Independence which was given some

attention in the paper, though mostly treated in general terms. No

reference at all was found to the mid-November 1919 killing by

Auxiliaries of Glynn’s Gurteen neighbour, Fr Michael

Griffin, though that episode was widely covered in the Australian

press. His closest engagement with the Irish conflict was the

excerpt from a personal letter from his friend Tom Barker that he

published, conveying the latter’s impression of Irish labour

radicals and of the Terence MacSwiney funeral. Glynn’s major

preoccupation at that time was that he be able to advocate for

industrial unionism within the deeply factionalised and fractious

CPA. Probably because he could not, he resigned as editor of

The Australian Communist at the end of March 1921, though

he continued to contribute to the paper for a time. Later in 1921,

he stood for election as general secretary of the miners’

union, but was narrowly defeated by the incumbent. Subsequent to

that, in December 1921, with some others he revived

Direct Action, with the intention of advancing industrial

unionism within the communist movement. It was a short-lived

initiative, however, which ended within a few months

Later life

Unable to find paid work in the political sphere, Glynn sought

casual labouring jobs on the Sydney docks and elsewhere. By May

1923, his health had broken down to the extent that the

Communist Workers’ Weekly launched a Benefit Fund

to tide him over. The response to the appeal enabled him to set up

a taxi business but he entered that field just as the Yellow Taxi

Company was pushing independent drivers out of business. By his

daughter Molly’s recollections, he was bed-ridden for much

of the rest of his life. A continuing political relationship

indicated by the lecture on ‘The life and works of James

Connolly’ that he gave in the Communist Hall in August 1923,

but toleration for a-la-carte Communists was diminishing with the

intensification of the Comintern’s

‘bolshevization’ strategy. He found a political home

in Jack Lang’s radical (and ultimately secessionist) New

South Wales Labor Party, though without any appreciable softening

of his views. Maintaining a public profile as a columnist in the

Lang-supporting Labor Daily, where much of his output was

on economic subjects, Glynn became more engaged with Ireland,

writing in generally approving terms, for example, about De Valera

and Fianna Fáil when they took office in 1932.

His last contribution to the Labor Daily was on 3 February 1933. Thereafter partial paralysis made it impossible for him to continue. A family connection was maintained, however, by his daughter and his South African son Jack, both of whom worked for the paper. On his death in early December 1934, the Labor Daily obituary remembered him as ‘a sincere and steadfast fighter [whose] … name will forever be identified with the great anti-conscription fight of 1914.’

Tom Glynn devoted his adult life to radical causes directed at working class liberation, and he continued to rail against injustice from his sick-bed until he was no longer physically capable of doing so. Internationalist in his politics and perspective, he nonetheless carried markers of his Gurteen childhood throughout his life: in the Irish language phrases remembered by his daughter, in his continuing identification as a Catholic in a largely freethinking milieu, and in his party-piece at Australian social gatherings which was Robert Emmett’s speech from the dock.

John Cunningham is a Lecturer in History at NUI Galway, and a former editor of Saothar: Journal of Irish Labour History. He is writing a full biography of Tom Glynn.