Global Lives: Patrick McCartan

By Brian Hanley

Dr. Patrick McCartan was recruited into Irish revolutionary politics as a young emigrant in the United States. He became intimately involved in contacts between the Clan na Gael there and their Irish counterparts in the Irish Republican Brotherhood prior to Easter 1916. Thereafter McCartan was a key player in attempts to broker agreement between Irish republicans and the Soviet Union, travelling between Ireland, Britain, the US, Scandinavia, Germany and Russia during the revolutionary period.

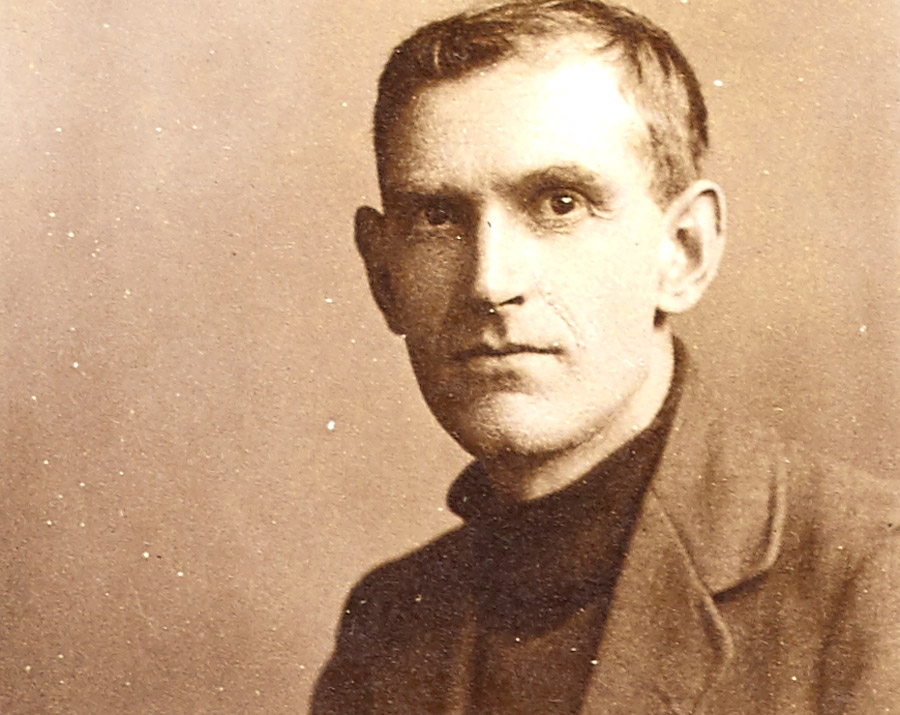

Born in May 1878 in Carrickmore, Co. Tyrone, McCartan’s

interest in politics was inspired by the United Irish Centenary

commemorations during 1898. But it was while working as a barman

in Philadelphia that he was enrolled into the Clan na Gael by

fellow Carrickmore man Joseph McGarrity. It was also McGarrity who

provided financial assistance to enable McCartan to return to

Ireland during 1905 to study medicine at University College Dublin

(he later graduated from the Royal College of Surgeons). Remaining

in contact with McGarrity, McCartan became involved in the

IRB’s Teeling circle and Gaelic League’s Keating

branch in Dublin. One of a number of younger IRB members who

pushed for the organisation to adopt a more militant policy, he

became editor of the organisation’s journal

Irish Freedom. He also wrote for John Devoy’s

Gaelic American. McCartan joined Sinn Féin after

1909, becoming a councillor for the party on Dublin Corporation.

After securing an appointment as a doctor in Tyrone he worked as

an organiser for the Irish Volunteers there during 1914. McCartan

took separatist rhetoric about welcoming the rebellion of the

Ulster Volunteers seriously enough to lend his car to the local

UVF during the Larne gunrunning. When the Volunteers split over

support for the war, McCartan was sent to the United States to

rally support.

Though a member of the IRB’s Supreme Council,

McCartan’s involvement in the Easter Rising in Ulster ended

in confusion. Volunteers from across Ulster gathered in Coalisland

in order to march to Connacht but the countermanding order from

Dublin led to demobilisation.

He went on the run in the aftermath, was arrested in early 1917 and deported to England. He returned illegally to Ireland and was part of discussions among the IRB leadership in Dublin to seek aid from the new Russian regime, which had come to power in the February revolution. McCartan was given plenary powers on behalf of the republican government and first tried to contact Russian émigrés in London. But his mission was diverted to the United States, where was sent with a memorandum from Irish republicans for the US President after the publicity surrounding Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points. McCartan sailed to New York from Liverpool posing as an able-bodied seaman on the S.S. Baltic, the favoured route for the IRB’s trans-Atlantic passageways. In October 1917 McCartan was arrested along with Liam Mellows in Halifax, Nova Scotia, while trying to travel to Germany to secure arms. He spent 10 weeks in jail in Canada and then travelled to the U.S. During 1918 he was an unsuccessful candidate in the Armagh South by-election (where his help for the UVF in 1914 was used against him) but a successful one in King’s County.

|

|

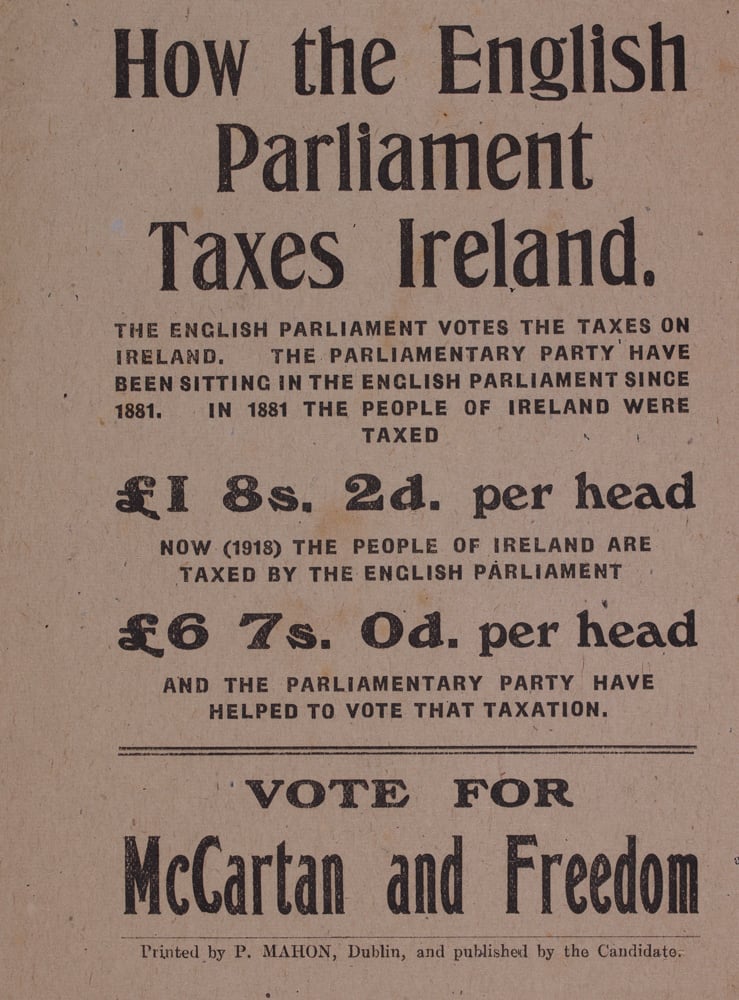

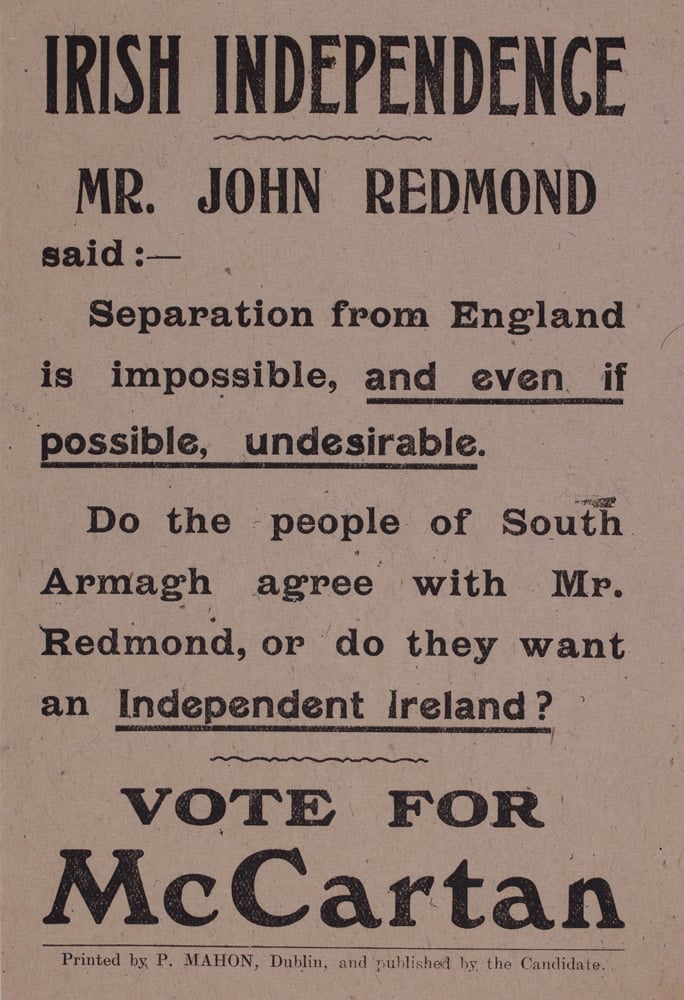

Posters in support of Patrick McCartan's unsuccessful candidacy in South Armagh by-election, February 1918. (Images: National Library of Ireland)

By 1919 McCartan had become the main Irish contact with Bolshevik representatives Santeri Nuorteva and Ludwig Martens in New York, developing a close relationship with the Finnish exile Nuorteva in particular. After Irish representatives seemed to distance themselves from Russia, McCartan responded in the socialist press: that ‘[between the] gallant starving isolated Russians striving against alien enemies (and) the Irish, also isolated in their struggle against British armies of occupation … there can exist only that sense of brotherhood which a common experience endured for a common purpose can alone induce.’ Privately McCartan worked hard with Nourteva to draft a mutual recognition treaty. He also explored the possibility of securing arms and trade deals with the Soviets but it was the Russians who ultimately received £20,000 from Irish republicans. McCartan took the prospect of securing Soviet support seriously, but felt that other Irish leaders, including de Valera, dragged their heels in fear of alienating opinion in an increasingly anti-radical America.

In the spring of 1920 he was smuggled back to Ireland, via Liverpool, to brief the Dáil on the splits among Irish republicans in the US occasioned by de Valera’s ‘Cuban’ analogy. Though he disagreed with de Valera’s stance he defended his position and sided with his old mentor McGarrity against John Devoy. He returned to New York in May and stressed to de Valera the necessity of securing an agreement quickly with the Russians. McCartan argued that ‘quick action in concluding a Treaty is the only thing that will justify us to many of our best friends. If the Mission is suspended in Moscow the enemy press of the world will say we were the innocent tools, or victims, of the Bolsheviks. The conclusion of a Treaty makes such criticism impossible, because we shall have gotten our quid pro quo.’ McCartan also demanded that he be given powers to conclude an agreement because ‘any Irishman arriving in Moscow to discuss the proposed Treaty must find himself in a humiliating position if he has not the power to conclude it, and the nation he represents must share in the humiliation.’ McCartan privately suspected that de Valera ‘was afraid we might get recognition.’

It was December 1920 before he sailed from New York to Scandinavia, having briefed Irish diplomat Gavan Duffy on developments in Copenhagen and eventually reached Moscow via Reval (Tallinn) during February 1921. McCartan’s firsthand impressions of Soviet society are contained in his statement to the Bureau of Military History. They offer cynical but insightful observations of a society struggling to survive after years and revolution and war. ‘Nobody in authority’ McCartan asserted, ‘pretends to think that such a thing as liberty exists there … The idea of whether or not the present regime represents the will of the people is openly laughed at … though it is claimed that the present Government is a dictatorship of the Proletariat it is nothing of the sort. It is a dictatorship of the Communist party which represents less than one per cent of the population of Russia.’ Despite Soviet pretensions to internationalism he found the Russians to be chauvinistic towards other nations, such as the Estonians. Nevertheless he still attempted to gain recognition, secure trade deals and perhaps gain arms supplies. He told his contacts that the ‘mere act of recognising our Government would have a great effect on the morale of our own people and was certain to have effect all over the world … Recognition of Ireland would make very genuine sympathiser with Ireland an active advocate of recognition of the Soviet Government.’

But realpolitik ensured that McCartan’s mission was a failure. In March 1921 the Soviets concluded a trade agreement with Britain. They were now torn between supporting Irish self-determination and maintaining good relations with London. Furthermore McCartan’s best contact, Nuorteva, having returned to Russian via England, was arrested and accused of being a British spy. McCartan lamented that ‘none of those who took his place had half his ability’ and suggested that ‘if he (Nuorteva) was not sincere in his friendship he is a splendid actor.’ Now McCartan heard Soviet complaints that Irish nationalism was purely ‘bourgeois’ and aware that he was unlikely to come to an agreement left for Germany during June. He spent a month there, meeting republican contacts who were attempting to secure arms. British Intelligence were aware that ‘MacCurtan (sic) was in Russia’ but were happy to note that ‘he was not received with honours, and left at the suggestion of the Soviet.’ Nevertheless the British used the abortive treaty to accuse Irish republicans of Bolshevik sympathies in June 1921.

McCartan returned to Ireland during the Truce period and was a reluctant supporter of the Treaty, fearing the consequences of a resumption of war. After he lost his seat in the June 1922 election and having ‘no time for civil war madness’ McCartan returned to New York. He published an account of his diplomacy With De Valera in America during 1932. He married actress Elizabeth Kearney, who had had met in New York and they returned to Ireland in 1937. In 1945 he stood as an independent republican candidate for the presidency and was later a member of the Seanad for Clann na Poblachta. In the fiercely anti-communist Ireland of the 1940s, the fact that republicans had once sought recognition from the USSR was largely forgotten, but McCartan had been a key part of trying to do so.

Dr. Brian Hanley is an AHRC Research Fellow in Irish History at the University of Edinburgh, working on the story of Ireland’s global revolution, 1916-23.