Global Lives: Margaret Cousins

Dr Jyoti Atwal

Margaret Elizabeth Cousins (née Gretta Gillespie; 1878-1954) was born in Boyle, Co. Roscommon in western Ireland. She was a prominent leader of the Irish women’s suffrage movement in Ireland, along with Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington. Margaret felt that she was born a natural equalitarian and rebelled against any differential treatment of sexes.

Her leadership of the suffragette movement in Ireland contributed to a remarkable phase in Irish history. Along with Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington, Margaret founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League in 1908. Her Tullamore jail experience in 1913 acted as a precursor to her politics of protest in colonial India. Almost 20 years later, Margaret was sentenced to one year of imprisonment at Vellore Women’s jail for participating in the Gandhian programme of protest against the Ordinances which choked the expression of the people of India.

Margaret’s Irish days were notable for her work with the Irish National Theatre, in which she participated with her husband James Cousins. A book called The Secret Doctrine (1888) had a tremendous influence upon her. She felt as if a new universe had entered her; and expanded her consciousness about time, space, ethnology, cosmology, symbolism and magic. In 1906, the Cousins were introduced to the Bhagvad Gita by Dr K.V. Khedkar of Kolhapur. Their home in Dublin was visited by Joyce, Yeats, and several actresses and actors from the Irish Literary Theatre, the National Dramatic Society, the Abbey Theatre and the Theatre of Ireland. In 1905, the Irish Vegetarian Society was organised, with Margaret as its secretary, developing connections with the Vegetarian Society in England.

Margaret Cousins (Image: Dublin City Library and Archives)

Margaret had connections with the suffragettes in London, especially Mrs Pankhurst. The essential disappointment of Irish suffragettes was the non-inclusion of women as citizens in the agenda of the Irish Parliamentary Party’s Home Rule proposal. Most Irish Home Rule politicians like Tim Healy, John Redmond, Hugh Law and Joe Devlin initially looked down upon Irish suffragettes as ‘gate crashers’, who were ‘interrupting’ the Cabinet Ministers. Militant suffragette methodology was adopted to publicise their demand for voting rights and to seek support for it, with Margaret writing:

Three of us volunteered to break the windows of Dublin Castle, the official seat of English domination. That sound of breaking glass on January 28, 1913, reverberated round the world and did what we wanted. It told the world that Irish women protested against an imperfect and undemocratic Home Rule Bill. We (Mrs Connery, Mrs Hoskins and myself) were marched from the Castle to the College Street police station, next to the vegetarian restaurant.

After moving to India in 1915, she organised the Indian women’s movement and committed herself to the Gandhian freedom movement. She had a long political career in India where she provided leadership to the Indian women’s political rights movement by carving out their role in the freedom struggle. She built camaraderie with highly significant Indian women such as Muthulakshmi Reddy, Sarojini Naidu and Kamladevi Chattopadhyay. Margaret was shaped by the complex beauty of the late nineteenth century Celtic revival in Dublin, and the humanitarian spirit of the countryside at Boyle. She arrived in Adyar (South India) with her husband James Cousins on the invitation of Annie Besant (President of the Theosophical Society). James H. Cousins was a well-known poet from Belfast. Through their association with Yeats and Russell, they developed a vibrant public life. Through their interest in politics, social agitations, and women’s movements in Dublin, their life centred around literature, poetry, plays, politics, Home Rule bills, the Gaelic League and Irish myth, folk dance and the occult. By 1914, due to what James labelled as ‘expulsive forces’, the couple moved to India:

Economically I was in a cleft stick….The attracting force came from India. Visitors from that country, intent on medicine and law, saw some possibility of service by us to education and womanhood. This added idealism and our growing desire for the touch of the posterity of the rishis and scholars and saints to economic necessity.

Sister Nivedita, born Margaret Noble in Co. Tyrone (Image: Select essays of Sister Nivedita, via the Internet Archive)

Most Western women associated with church or charitable/educational institutions in colonial India had been nurses, nuns, teachers or social workers. However, a new variety of spiritualists/feminists/nationalists in colonial India came from Ireland where their unique experience of Celtic revivalism, mysticism, occultism, literary and cultural rootedness were combined with anti-colonialism. Margaret Cousins and Sister Nivedita, both Irish women, differed from each other in their trajectory of involvement in the anti-colonial movement and the women’s movement in India. Sister Nivedita had been born as Margaret Noble in Co. Tyrone in 1867. Quite early in life she had travelled to England where she was inspired by teachings on modern Hinduism and Swami Vivekananda, whereas Cousins was a Theosophist. Cousins believed in collective political action rather than the formation of communal cohorts by appealing to a religious past.

Margaret taught school children at Madanapalle while James worked as a newspaper editor and later as the principal of the Theosophical College. Rabindranath Tagore was invited as early as 1919 to Madanapalle. His visit to Madanapalle holds great historic significance, as it was here during his brief stay that Tagore asked Margaret to give music to the English version of ‘Jana Gana Mana’. The original song in Bengali is sung today as the national anthem of India. Its translation into English was carried out by Tagore at Madanapalle. The English version is called the ‘Morning Song’. Tagore’s song includes geographical reference to various regions, mountains, and rivers of India. The second verse refers to religions of India. The song ends with a louder ‘jayahai, jayahai, jayahai, jayajayajayajayahai!’ (‘victory, victory to thee’). This song was a moment of integration for the Cousins - they felt that they were ‘some kinds of agents in the Karma of India’, as Kamaladevi Chattopadyaya would later remember:

One day she (Margaret) offered to teach me a song which she had learned from Tagore himself. It was ‘Jana Gana Mana’ which was one day to become the national anthem of free India.

During her early days in India, Margaret realised that she was an enigma to the various local sections because ‘the Catholics could not understand how an Irish woman could be both a Protestant and a Home Ruler. The Protestants could not understand I was not a missionary’.

During the 1920s Margaret drew closer to the Gandhian philosophy of non-cooperation with the British which was launched as a response to the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in 1919. In 1923 she accepted an invitation from a local Hindu elite to become a Honorary District Magistrate of Saidapet Court of Madras. She stated that she would accept this invitation as it had come from an Indian, and not from a representative of the colonial state. She mostly administered civil cases and had the heads of different religions in India by her side to help her with law books. She gave up this position after a year.

The frontispiece of The Awakening of Asian Womanhood, by Margaret Cousins. Click here to view the book in full on the Internet Archive

In 1922, Margaret wrote a book, entitled The Awakening of Asian Womanhood, in which she laid down some universal principles concerning womanhood. The book is a fascinating character analysis of Asian women (Muhammedan, the Jewish, the Indian, the Burmese, the Chinese, and the Japanese). She referred to a rising in the hearts of Asian womanhood of a mighty wave of desire for freedom. The World Conference of Communist Women held at Moscow in 1921 was attended by 25 women delegates from the Near and Middle East. In India, Margaret was deeply concerned about the custom of child marriage and the lack of education and freedom among the girls. In 1921, there were over 10 million girls who had been married between the ages of 10 and 15. She pointed out the social protest against these regressive practices by Hindus themselves. Some sections of Indian society were making efforts but it was not adequate. It was ‘self-determination’, according to Margaret, which was necessary for the individual man or woman, as much as caste, class or nation. For her, ‘religion, education, patriotism and love’ were four liberators of women: ‘the whole time spirit is working towards the liberation of woman in very country, but along different lines according to the different civilizations’.

The Reforms of 1921 remained silent on the question of Indian women’s voting rights. Later, the Southborough Committee was formed to gather evidence on whether Indian women really wanted franchise. In 1924, a Reforms Enquiry Committee began gathering more evidence. Finally, the ban on women’s right to vote was lifted in 1927. Conditional upon their property qualification, they could now vote and also run for a seat in the State Provincial Legislatures. Margaret ran such a campaign for Kamaladevi Chattopadyaya by pulling local resources together. When Devi lost, Margaret kept the spirits of the women high by asking them to work locally for the national cause. Chattopadyaya would later comment:

It was Gretta [Margaret] who organised the campaign, publicity, volunteer corps and all the necessary paraphernalia. Music and cultural shows were introduced at election meetings which people thoroughly enjoyed. An entirely different atmosphere was created by Gretta’s creative brain and all tension, vulgarity, abuses were scrupulously avoided. The band of volunteers with dark blue badges, had a sense of purpose, an emotion of romance and chivalry injected into them by the style of the campaign. ..Gretta worked very hard and mad everyone else work too.

Two highly significant associations, the All India Women’s Conference and the Women’s Indian Association, were launched by Margaret and Annie Besant with the support of Indian women. These associations continue to offer extraordinary service to women in modern day India.

Margaret differed from most of the Western women who had visited India and written about it. She hoped that despite the fact that India was suffering under British colonialism, and serious social challenges, that one day the women of India would lead the women of the East in all public movements as they were the first to get their hands on the helm of government. It is interesting to note that she critiqued the American journalist Katherine Mayo in an essay entitled ‘Miss Mayo’s Cruelty to Mother India’ in an issue of Stri Dharma magazine in 1934. Mayo’s book, Mother India (1927), had been an indictment of India, wherein she condemned Indians as a race. Her facts were random and selective. The Indian leaders of the freedom struggle had responded the same year by writing books strongly countering her narrative. Margaret called Mayo, a ‘morbid pathologist’ and ‘a lady with a muck rake’, writing: ‘I am a lover of humanity, and work for it through seeking advancement of womanhood to an equality of honour and opportunity with manhood’.

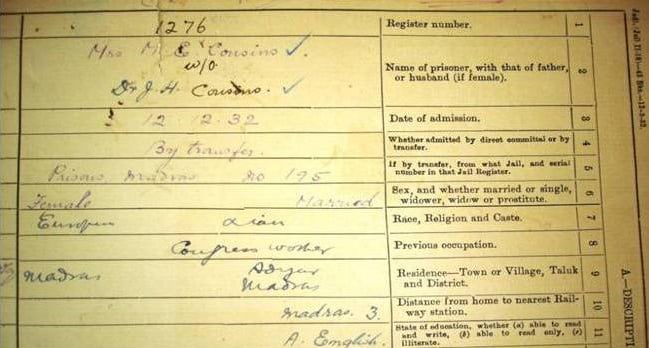

Margaret Cousins' jail record (Image: Tamil Nadu Prisons Department)

In 1932, as a response to Gandhi’s call for a Civil Disobedience Movement, Margaret violated government ordinances against public speech and public gatherings. She was arrested in 1932 and sentenced to a year-long imprisonment at Vellore Women’s Jail. During her imprisonment at Vellore, Margaret was reminded of her prison experience at Tullamore in Ireland. At Vellore she was permitted to meet friends and her husband, and to receive books (but not newspapers). Margaret’s contribution to the Indian freedom struggle was recognised by the Indian State and she was honoured with a National award after independence in 1947. Unfortunately, Margaret was paralysed from the 1940s until 1954, and so was inactive in public life. Her legacy of women’s rights, democratic values, and women’s economic uplift lives on today in India in the form of the All India Women’s Conference and the Women’s Indian Association. These institutions have continued to serve Indian society and empower the women of India through various public schemes and support systems.

The life and times of Cousins poses an interesting question for the historiography of the politics of complicity and resistance by Western women in colonial India. The historiography on Irish women has been quite inward, with a focus on the political chronology of events in Ireland. The Irish women's movement lost its independent character after 1912 as the idea of Home Rule (Irish Nationalist Party and Sinn Féin) and labour (The Labour Party) took over. Later in 1916, the association of radical women, named Cumann na mBan, devoted itself entirely to the organisation of the 1916 Easter Rising. The question of transnational feminism has been ignored in women’s history writing. This has primarily happened due to the presupposition that Indian women’s activism represents an underdeveloped phase, and that Western women failed to radicalise these sisters.

The present scholarship does not explain the complex phenomenon of Western women’s political encounters with the East. Margaret Cousins stands as a historical figure that seeks to challenge some of the trajectories/frameworks within which East-West feminist relations are conceptualised in existing scholarship.

Margaret Cousins with Nehru and Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy in the late 1930s (Source: We Two Together by Margaret and James Cousins. Click here to view the book in full on the Internet Archive)

Dr Jyoti Atwal is Associate Professor of History at Jawaharlal Nehru University, and Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Limerick. She was recently a Visiting Fellow at the Moore Institute, NUI Galway.