Global Lives: Daniel McAuliffe

By Patrick Mahoney

On 3 January 1920, Éamon de Valera arrived in the city of Hartford, Connecticut, to a raucous reception from over 3,000 supporters. In many ways, Hartford is emblematic of the strength of diasporic engagement with the revolution in Ireland. The surplus of factories and mills that sprang up along the Connecticut River during the 19th century ensured a constant inflow of migrants to the booming industrial hub. Particularly strong migration links with the west of Ireland developed, with many immigrants maintaining strong ties to their home culture. One such individual was Daniel McAuliffe, a native Irish-speaker from Ballynoe in East Cork, who had arrived in the U.S. in 1898. McAuliffe’s story offers unique insight into Irish-American bicultural identity during the revolutionary period, and also conveys how individual movement and spatiality shaped the social and political beliefs of individuals within well-established Irish-American communities.

McAuliffe became actively involved in Hartford’s plethora of Irish political and cultural organisations. As manager of the city’s Michael Davitt Club Gaelic football team, he made contacts throughout New England, and travelled regularly to face teams in New Haven, Bridgeport, Waterbury, and Springfield, Massachusetts. Historian Gearóid Ó Tuathaigh notes that Gaelic games in America at the outset of the 20th century served consciously as ‘important markers of Irish ethnic identity’ and promoted a ‘virulent, revolutionary strain of nationalism’ even after the failed 1916 Easter Rising.

This was certainly the case for McAuliffe’s Davitts. The club was connected with a local branch of the United Irish Societies of America, which regularly scheduled lectures, concerts and events to commemorate ‘the lives of Irish martyrs and patriots’. Though the national organisation was known to be rather conservative, the Hartford branch was often more militant in their rhetoric, and on a number of occasions, publicly drilled in the city streets. A cross referencing of membership lists with the local Conradh na Gaeilge branch reveals that the Michael Davitt Club had a particular resonance with Irish-speaking immigrants like McAuliffe, as is also evidenced by the incorporation of bilingual aspects to their proceedings. For example, at a 1908 commemoration of the Manchester Martyrs, it was noted that a member of the club lectured ‘in the Gaelic tongue.’

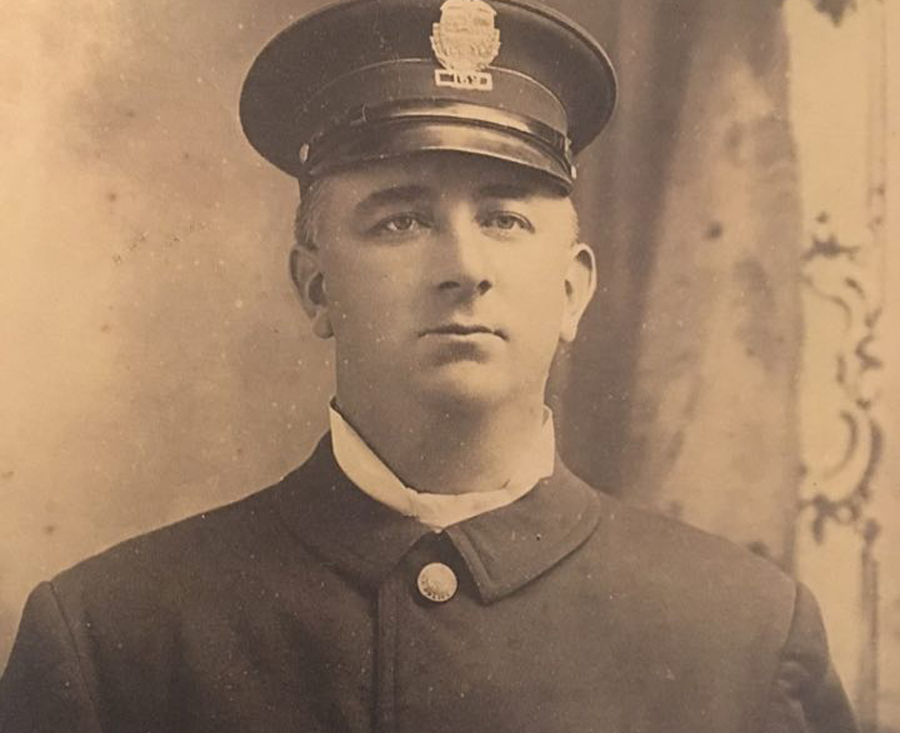

It was through his role as a local representative of the Friends of Irish Freedom (FOIF) that McAuliffe became involved with the reception committee for de Valera’s visit. Given his day job as a police detective, McAuliffe served as head of security detail for De Valera’s inaugural visit.

The FOIF was founded with popular support in March 1916 at the first Irish Race Convention in New York City as a source of fundraising and political lobbying. By the time of De Valera’s tour in 1920, the organisation’s membership was upwards of 100,000, with branches in all of the major US cities.

However, after De Valera’s highly publicised falling out with John Devoy, Judge Daniel F. Cohalan, and other Irish-American leaders, he founded a rival organisation in October 1920. Known as the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic (AARIR), the organisation had a strong footing in Hartford, where local Irish Republicans remained dedicated to the financial welfare of De Valera’s aims. Cited amongst the specific reasons for the associational shift, Hartford’s Irish republicans noted their dissatisfaction with the inactivity of the older national body and its leadership. Additionally, they stated their belief that the AARIR’s amendment to allow sympathetic American citizens with no Irish familial connections to join would undoubtedly boost membership and further their aims at both the local and national levels. Circumstantially, a visit by Mary MacSwiney in January 1921 also played a pivotal role, as she announced that she would only fulfill her speaking obligation under the auspices of the AARIR.

Reflecting this grassroots shift in the Irish republican politics of the city, McAuliffe followed this general pattern of membership, first joining the local Friends of Irish Freedom, and later the local AARIR chapter, which became known as the Pádraic Pearse Council. Reflecting on McAuliffe’s outlook and possible motivations for participation within the organisations, his friends relayed that: ‘[he] was always a most radical talker concerning the disturbed affairs in Ireland. He was a vociferous advocate of fighting England to drive her from Ireland, a great admirer of De Valera, and he asserted many times that just as soon as the republican army had won its battle for complete independence, he would go and settle in the country of his nativity.’

In the years to come, it was his relationship with Michael Collins, not De Valera, that dominated local headlines. On 21 January 1922, McAuliffe approached his superiors in the Hartford Police Department and sought vacation time to visit a sick relative. Unbeknownst to his superiors, McAuliffe had applied for a passport four days previously with the intention of returning to Ireland to ‘settle an estate’. Before a decision could be made by the Police Department, McAuliffe had already left Connecticut. His resignation was posted from New York City after he set sail for Ireland.

Civil War was looming by the time McAuliffe arrived in Ireland. Almost immediately, he became involved in training the fledgling Civic Guard. The Hartford Courant reported that McAuliffe’s return was born out of a desire to ‘Stand by Mike’ and that the two had been friendly while growing up in County Cork. Within the local press, McAuliffe’s narrative was often framed in terms of his personal connections to the two republican leaders and their split over the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. One report used the Hartford resident as a personification of the deeply conflicted Irish-American community itself, noting: ‘thrown in the dilemma of all Irishmen...What would McAuliffe do?’

Before his dramatic return, McAuliffe had already proven invaluable to the revolutionary movement. During his time as Detective Sergeant in the Hartford Police Department, he bought a sizeable number of handguns from various pawn shops. The cache, which most notably included a number of Colt .45s and .38 caliber Smith & Wessons, was inconspicuously sent back in increments to support the IRA guerilla campaign. The participation of Connecticut police officers in IRA gun running is further evidenced by Limerick Volunteer Edmond O’Brien’s statement to the Bureau of Military History. Sometime after O’Brien’s arrival in the US in February 1920, Harry Boland directed him to deliver a store of weapons from Waterbury, Connecticut, to the Port of New York and New Jersey. Significantly, he recalls receiving a guarded escort from ‘at least one member of the American Police Force [in Connecticut]’ who was ‘aware of [the] mission and knew what was in the cases.’

At the time of his departure, the local Hartford press reported that McAuliffe was one of 60 ‘secret agents’ serving various roles for Collins in the US who had been called back to Ireland. Given available sources, namely the information recorded in the Free State Army census and IRA pension files, the existence of any further agents working in a similar capacity is difficult to confirm. Consulting the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) records, McAuliffe was one of only five agents with foreign ties, the others being former British Army members and one German national who also noted a connection to Collins. However, in McAuliffe’s application for a position to the department in the summer of 1922, he didn’t mention his friendship with Collins or any previous republican connections. Instead he lists his background in the Hartford police department as providing a transferrable skillset. Indeed, McAuliffe’s wife refuted the earlier rumors of childhood friendship between McAuliffe and Collins, instead noting that her husband first met Collins after his relocation to Ireland.

While his involvement in gun running circles likely contributed to his desire to play a further active role in the revolution, issues closer to home might have also played a role in his abrupt transatlantic trajectory. At the time of his disappearance, his brother Thomas, a state prohibition enforcement officer and fellow Hartford resident, was under investigation for bribery and corruption. As State Attorney Hugh M. Alcorn began investigating his activities, he also considered possible complicity on the part of the disgraced official’s brother. McAuliffe was not without his own controversies. A year before his departure for Ireland he had been pursuing a group of drug addicts when he fired two shots at a suspect who he later claimed had assaulted him. One of the bullets ricocheted off a curb and struck a bystander. Despite intense debates within the department, McAuliffe was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing.

Two months after McAuliffe left for Ireland, his wife, Ellen, filed for a passport for herself and her three sons to ‘visit’ their father. However, it soon became clear their stay was intended to be more permanent. Not long after landing, 18-year-old ‘Danny’ McAuliffe joined the recently expanded Free State army. Although raised in Hartford, he was born in Cork during a family visit. This biographical detail was invoked time and time again. In one statement to the press, his mother noted that her son ‘was (by age) eligible, and more so than many others who were in the army, as he was born on Irish soil.’

This issue of spatiality and identity is further evident in an attack on De Valera waged by Ellen McAuliffe based on what she purported was information obtained by her ‘husband’s men’ in the CID. She noted, ‘Ireland, that is Free State Ireland, is out of patience with de Valera’s opposition to what seems the best interest of Ireland...In Dublin De Valera is not regarded as an Irishman...They know that he is the son of a Spaniard whose wife was of Irish descent. De Valera, they report, was born in New York City, and so was his mother...the natives of the island do not regard de Valera as one of them, although they do generously acknowledge that he was a great help in the early years of the movement.’

Although De Valera’s American birth was well-known and publicised during the period, McAuliffe’s erroneous allusion to his mother’s American birth and father’s racial background as a point of discreditation, coupled with the emphatic allusion to her son’s status as ‘Irish born’ when referring to his Civil War service, offer insight into ‘Free State Ireland’ and Irish American views regarding the appropriate level of diasporic intervention in the affairs of the home culture, based upon one’s place of birth and their familial connections.

The younger McAuliffe returned to Hartford in November 1922 after only six months of service in the army. Upon his return, he provided a number of curious recollections of the Irish-American elements within the Free State Army which have often been overlooked within the historiography of the Irish Revolution. In one instance, he noted: ‘I met some of the boys from the old ‘69th Regiment’ of New York when in the army, and many of the American veterans of the World War. Some now hold high positions in the Free State Army, and declare they are happy and contented and sure they are on the right side of the struggle to establish the government.’ Historically speaking, such participation is hard to document. The Free State Army Census does not list place of birth or sufficient details to establish the composition of its membership. McAuliffe’s allusion to a multitude of U.S. veterans who had gone over and ‘selected the right side’ may also have been a covert call-to-arms for Irish-American World War I veterans to do likewise and offer their services to the Free State, which was in dire need of recruits after the execution of Liam Mellows had shifted international public opinion.

Dan McAuliffe Sr. also rejoined his family in Hartford on Christmas eve 1922. Initially, he indicated that he was still employed by the CID and back in the States on official business; presumably to look into the status of the contested Republican funds, which had been raised during de Valera’s tour ($10,000 of which had been raised in Hartford). McAuliffe was adamant that he intended to return to his position in Dublin within two months. However, he never made the return trip. Curiously, the Corkonian is not listed amongst those who were dismissed or retired from the CID amongst the department’s final reports.

Muriel MacSwiney doubted the veracity of McAuliffe’s position as a CID agent. Addressing a packed crowd in the Church Street Auditorium in Hartford in April 1923, she informed her listeners that ‘during most of the time that you say this McAuliffe was in Ireland […] we knew all of the Free State officials... Especially the secret service men... it was to our interests to know them.’

McAuliffe offered no public retort to MacSwiney’s claims. However, following the assassination of Kevin O’Higgins in 1927, the former police detective – now working as a security guard for a private agency – provided a statement to the local press about the killing and elaborated on the reason for his return. Differing from his initial explanation that he had temporarily returned on official business, McAuliffe claimed that O’Higgins offered him a position on the Garda Síochána in November 1922. However, he contended that ‘acceptance of that offer meant that I would have to take the oath of allegiance to the Free State government on December 6, which also meant that I would have to surrender my American citizenship.’ He further quipped that ‘with regard to once again becoming an English subject [he] had his fill of it during his 11 months in Ireland.’ Indeed, the Constitution of the Irish Free State came into effect on the date provided by McAuliffe. As such, any person born in Ireland or with Irish parentage, and those ‘domiciled in the area of the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State/Saorstát Éireann for not less than seven years’ were regarded as Irish citizens. McAuliffe’s declaration raises interesting questions about citizenship and identity during the revolutionary period, given the constitutional proviso that ‘any such person being a citizen of another State may elect not to accept the citizenship hereby conferred [by the Free State].’ In a manner akin to earlier Fenian conceptions of an ‘Irish government in exile’, for many US-based Irish republicans like McAuliffe, identity and citizenship weren’t necessarily inseparable even after the implementation of more rigid migration restrictions and the attainment of the dominative Irish Free State.

McAuliffe’s rejection Irish Free State citizenship was once again highlighted in an article to mark his first return to Ireland in the autumn of 1949, following his retirement from Hartford’s Parks Department. The piece rehashed his earlier sojourn in Ireland with exaggerated language, exclaiming: ‘Dan McAuliffe is going back to Erin where once he hunted Eamon De Valera [sic] through cities teeming with rebellion in a cloak and dagger chase which almost cost him his life.’ In contrast to this highly charged retelling of his exploits to mark his sole return, there was very little local coverage when McAuliffe quietly passed away in a local convalescent home on 21 November, 1964, at the age of 86.

McAuliffe’s story conveys a bilateral sphere of influence in which members of the diaspora unhesitatingly returned to Ireland with the intention of impacting the political landscape of the home culture. Brian Dooley touches upon this dynamic in his study of second-generation Irish in Britain, noting a plethora of individuals ‘from 1st to 4th generations’, who travelled to Ireland (some for the first time) to participate in the Easter Rising and ensuing guerilla campaigns. In the same way, the actions undertaken by individuals like McAuliffe, however varied their motivations might have been, help to broaden understandings of Irish America as a political entity beyond its capacity as a space of mobilisation for political jockeying and fundraising, or as a safe-haven for republican ‘exiles’.

Patrick Mahoney is Caspersen Fellow at Drew University and is currently serving as a Fulbright Scholar at NUI Galway. His most recent publication From a land beyond the wave: Connecticut’s Irish rebels, 1798-1916 (Connecticut Irish American Historical Society, 2017) won the Connecticut League of History Organizations’ Publication Prize in 2018.