From Belfast Jail to Blackrock tragedy: the death of Sinn Féiner John Gaskin

By Alyson Gray

John Gaskin was a man of many names. When searching for him in the various records related to the revolutionary period – census, police reports, prison and death records, newspapers and Bureau of Military History witness statements – he can be found referenced as Gaskin, Gascoyne, Gascoygne, Gascoigne, Gascoingne, Gasocigne, and Gascoigne.

Whatever the confusion about the spelling of his name, there was no mistaking his Irish republican credentials. Young, dedicated and involved in all facets of the movement towards Irish self-determination, he was an active member of Sinn Féin, the Volunteers, the Gaelic League and had served time in Frongoch after the 1916 Easter Rising. Participation in illegal drilling resulted in his imprisonment in Belfast Jail in 1918. Yet upon his release he remained resolute and worked as part of the campaign team to secure George Gavan Duffy the seat for South County Dublin at the 1918 General Election.

Like many young men of his era, Gaskin’s republican apprenticeship was served during the Easter Rising. One of the many actions he was involved in as a 19-year-old was cutting telegraph wires at Merrion Gates in South Dublin. On 2 May 1916, as part of a large round-up he was arrested and brought to Richmond Barracks. He was later transferred to Stafford Prison on 8 May 1916 and from there moved to Frongoch Interment Camp in Wales.

Gaskin survived his incarceration, but by the fourth anniversary of the Easter Rising, he was dead.

Newspapers reported how Gaskin, a ‘well-known Sinn Féiner’, was found ‘shot dead on a piece of waste ground in the Dublin coastal suburb of Blackrock in an incident that saw 17 year-old Agnes Byrne seriously wounded.’

Gaskin’s death, it subsequently emerged, was the result of a gunshot wound inflicted upon himself moments after he had shot Agnes Byrne. On Sunday night, 25 April, John Gaskin had attended a dance in the O’Byrne Social Club, leaving the dance to return home and then head back out again. According to press reports, it was while on his way back out that he spotted Byrne with some friends. The pair were neighbours both living near Brookfield Terrace in Blackrock. It was alleged that Byrne’s parents had refused to give their permission for her to marry Gaskin, owing to her young age. It was further alleged that Byrne herself had repeatedly declined Gaskin’s invitations to date or dance. On the Sunday night in question, Byrne and her friends walked up Carysfort Avenue and then along Brookfield Avenue, where three shots rang out and Byrne was seen to stagger and collapse. Gaskin’s body was found shortly afterwards in the centre of a nearby playground with a wound to the head, his revolver some distance from him. Inspector Bell of the Dublin Metropolitan Police noted at the inquest - held the following day - that the revolver was an old military bulldog design and a ‘most unsafe weapon.’

Left: John Gaskin. Right: Agnes Byrne, taken three years before the incident. (Image: Evening Herald, 27 April 1920)

Also giving evidence at the inquest was John Keane, a neighbour of Gaskin and Byrne. Keane stated that ‘he had often noticed Gaskin walk up and down Brookfield Place watching the girl as she went to her meals.’ Others who gave evidence claimed that Gaskin, who didn’t drink, had been acting in a peculiar manner and appeared like he was ‘anxious for a fight’ or that his behaviour, on the fateful night in question, seemed ‘agitated, irritable and strange’.

In her own testimony, submitted from Monkstown Hospital, Agnes Byrne recalled: ‘I was going home on Sunday night. I know him… I was with the girl Perry, Archbold and Byrne. It was just at the gate. I heard three shots. I saw him stand there. I knew no more until I found myself here. He used to ask me to go out with him. I would not go out with him. He threatened to do something to himself.’ Byrne further testified that she did not actually attend the dance. So what was she doing in the vicinity of the venue? According to the Irish Independent, Byrne had been ‘visiting the caretaker of the O’Byrne Social Club, Mrs Redcar on Sunday night, while others state she was at the dance but did not take part in it.’

The funeral of the 22 year old Gaskin took place in Blackrock on 28 April 1920. Shortly after 2 o’clock at Blackrock Church, his coffin, draped in the republican flag, was borne on the shoulders of Volunteers and carried to a hearse. More Volunteers marched either side as the cortege proceeded to Blackrock Cross, where the procession paused momentarily and prayers were recited again. The funeral then continued to Deansgrange cemetery.

The procession from church to cemetery was large and included members of the Dún Laoghaire, Blackrock and Deansgrange Sinn Fein clubs, Volunteers Corps and Cumann na mBan. The route was lined by Volunteers and a priest said prayers in Irish as the remains were finally lowered into the ground. All the traditions of a republican funeral were observed.

|

|

Left: The location of the shooting in Blackrock, Co. Dublin. The 'x' shows where Agnes byrne was shot. The arrow shows the playground where John Gaskin was found dead. Centre: Agnes Byrne and her friend. Right: John Gaskin's father in conversation with friends before the inquest. (Images: 28 April 1920, Freeman's Journal)

The question that lingered was why Gaskin had done what he had at all. Was it simply an infatuation with Byrne that drove him to attack her and then turn the gun on himself? Or was there a deeper underlying issue? Gaskin's father implied the latter in his evidence to the inquest, pointing to how his son's mental health suffered after the incarceration in Belfast Jail. The time served by Gaskin in Belfast had, his father claimed, ‘affected his mind’ and he had been in a downhearted mood ever since.

Gaskin was arrested on 1 May 1918 on a charge of drilling in Deansgrange on 24 April 1918. The police report from his arrest places him in the Deansgrange Sinn Féin Club leading a meeting with fellow member William Pedlar, encouraging the men in attendance to procure weapons. Constable Molloy added that both men were ‘dangerous’ and had been watched by police for some time: ‘Gascoigne and Pedlar are both active Sinn Féiners and were both arrested and deported at the recent rebellion. They are dangerous characters and have been reported upon by me several times.’

Gaskin was sentenced to three months hard labour, with one extra month if bail was not presented. He entered Belfast Jail that summer in what at first seemed to be a relatively calm atmosphere – although 1918 would end up being a tumultuous year for the prison. Fellow inmate Charles Kenny recounts that in the first half of 1918 the prisoners were permitted to wear their own clothes, hold daily meetings, receive food parcels and other packages from outside, take the windows out of their cells for fresh air and were given a special prison diet superior to the one given to those serving sentences for ordinary criminal offences. The prisoners received this special status and treatment due to terms negotiated in the aftermath of the death of Thomas Ashe, a republican prisoner who died in Mountjoy Jail after being force-fed while on hunger-strike in 1917. Anxious to avoid a similar incident developing in other prisons around the country, the authorities agreed that the prisoners would be afforded a special status, which allowed for the luxury of receiving food parcels from friends outside.

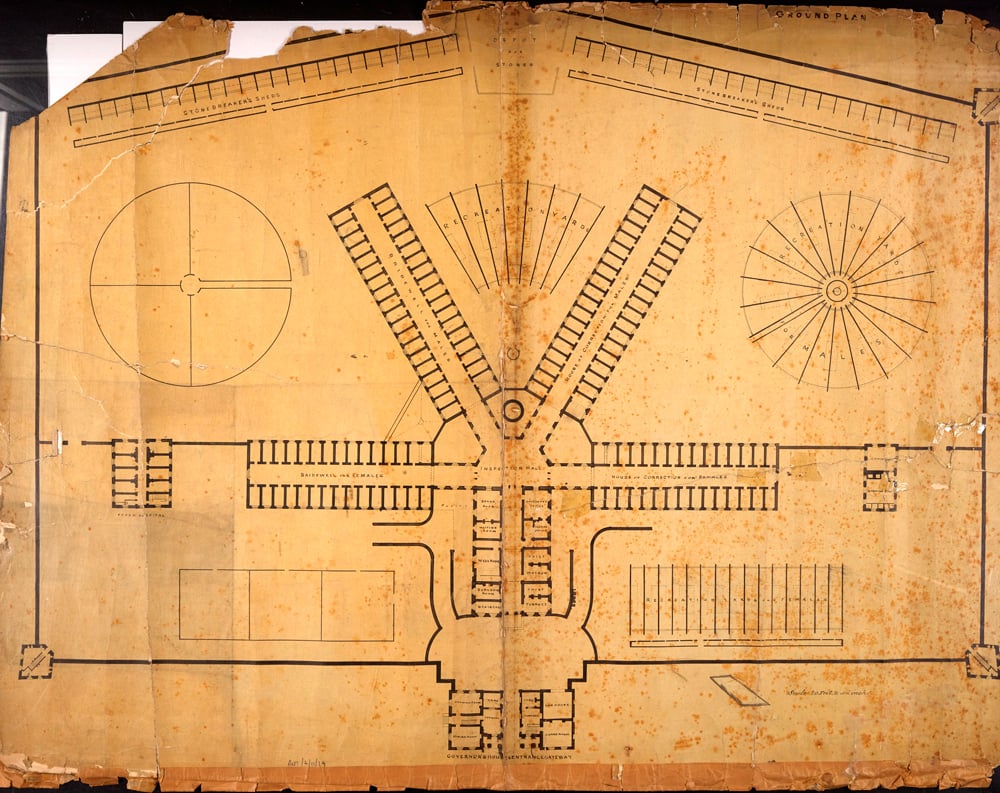

These food parcels were a crucial part of keeping the spirits of the men up and a necessary supplement to the sparse prison diet. However, when the leaders of Sinn Féin were arrested as part of the so-called ‘German Plot’ in May 1918, the men in Belfast Jail chose to reject the food parcels, leaving them only with the food provided by the prison. In the meantime, the rationing in place due to the ongoing Great War had become more stringent, so the men were left with very little to eat. Anger over this meant by the end of June the situation came to a head and many prisoners, including Gaskin, voiced their frustrations by singing and shouting from their cell windows which overlooked the Crumlin Road, attracting a crowd of protesters. As mentioned in Kenny’s statement the windows had been opened to offer more fresh air during the summer months, but to prevent the singing and disturbances, the Governor, William Barrows, ordered that the windows be boarded up while the men were out in the yard. Barrows also ordered the men overlooking Crumlin Road to be moved, an action which sparked a fierce riot on the night of 27 June, in which cells were smashed and prisoners were alleged to have been mistreated by the prison guards and police.

Later, some of the men, including Gaskin, gave statements as to their ill-treatment. The accounts tell of a terrible night during which there was a great deal of chaos, noise and violence. Many men were injured in the removal from their cells, and were placed in holds without proper provisions such as toilet facilities or beds. Others told of how their cells were filthy and crawling with insects. Reports of being left in handcuffs or muffs for an extended period of time were frequent, as well as being left in damp clothes after the guards sprayed them with hoses while removing them from their cells. In his account of the event, Kevin O’Higgins said ‘when the memory of the bludgeon and the hose and the physical hardships endured have passed away this feature of the case will remain branded in all our minds as the most revolting in that ten days orgy of brutality.’

John Gaskin’s personal statement is intriguing because it displays a great deal of distress despite not appearing to get as badly treated as many of the others, at least physically. He seems particularly distressed at having to watch the brutality being inflicted on his fellow inmates. He describes the night as ‘awful’, and with ‘all kinds of noises… going on all around me – banging and scraping’ when the warders arrived to move the men. He barricaded his door, after receiving instructions to do so from his prison neighbours. ‘At length they broke in and I immediately lay down and explained that this was my mode of protest, so they had to carry me down stairs to cell A in the basement. There I broke a window and a hole through the wall, also the spyhole so that I could see the rest of my comrades being brought down by the RIC who had arrived in the meantime.’ Once in his cell he sat down for a minute but ‘hearing the cries of someone being brought down, I rushed to the spyhole…’ From here he witnessed the rough treatment given to McMahon, John McKenna and Martin Corry. McKenna outlines this incident in his own testimony: ‘The young policemen… then caught my left hand and twisted it up between my shoulders while the man in civilian clothes twisted my tie so tightly on my neck that I thought I should choke. I was then torn out on the landing and down the stairs head foremost. The man in civilian clothes tearing me along by my necktie. … That night – I shall never forget.’

Gaskin spent the following day in handcuffs. The day passed without incident until he needed to relieve himself and the warder denied him access to the toilet. ‘I could not bear my burden any longer and had to use the cell floor instead of a lavatory’ he recalled. ‘Then I found I could not fasten myself up and had to walk around holding my trousers as best I could. I remained in that state until the warder… fastened it up for me.’ Many men told similar stories of having to use their cell floors as their bathrooms, made even more inhumane and difficult due to the fact that they were handcuffed.

In their statements the men note having to go to mass on Sunday morning, still in their handcuffs. ‘All those in the lower part of Chapel being in handcuffs and went to the communion rails in the handcuffs and in an unshaven filthy condition’, John McKenna recalled. ‘I certainly thought the sight a revolting one. It was only then I learned that some of them had been sentenced to 14 days bread and water for ‘mutiny’ – so-called – on Saturday morning.’ It appears that Gaskin was one of these men, he said: ‘I felt terribly humiliated at having to receive the Sacred Heart under such conditions.’

Plan of the ground floor of Belfast Jail from 1842, when the prison was used for women. In 1918 the republican prisoners were located in the wings facing Crumlin Road, which ran along the entrance to the prison. (Image: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland.)

Gaskin’s statement reads as more emotive in comparison to the other inmates, but he was far from alone in being seriously affected by the Belfast experience. Statements given to the Bureau of Military History many years later point to the impact on the wider community of inmates. Frank McGrath, Commandant, Tipperary No. 1 (North Tipperary) Brigade, spent six months in Belfast, and took part in the mutiny in the prison. He was in and out of jail again throughout 1919 and 1920, in his witness statement he said ‘due to my prolonged periods of imprisonment and due to the after effects of the hunger strike, my health deteriorated during the summer months of 1920 and I found myself reluctantly compelled to resign from the post of Brigade C/O.’ John McKenna from Listowel, Co. Kerry also spent most of 1918 in Belfast Jail, he said ‘After my release I was over 12 months in hospital. I came home early in 1920. This was practically the end of my contact with the IRA as through my state of health, I was unable to bear the strain any longer.’ Michael Brennan, Lieutenant-General from Dublin, stated: ‘Shortly after coming home (from Belfast in January 1919) I met Sean Treacy in Limerick and we had a long discussion on the general situation. We came to one definite conclusion – that we had more than enough of prison and we were not going back there again.’ Ex-inmate Thomas Flanagan also wrote about the incident in a letter to a friend: ‘I am not the same chap since it happened … down to the doctor every second day of course you can keep that to yourself. I tell my people at home the very opposite.’ In his witness statement Ernest Blythe also notes that two prisoners were committed to mental institutions after their time in Belfast in 1918.

When riots and mutinies weren’t taking place, the prisoners had to contend with the worst enemy of all: boredom. The men entertained themselves in various ways: in his witness statement Art O’Donnell remembers drilling and Irish classes taking place, along with physical training and sport. Debates and mock trials were acted out, and two in-prison publications were created. ‘The Jail Birds’ Journal’ edited by Seamus Murray and Seamus McEvily, and the Ernest Blythe-edited journal, ‘Glór na Corcrach’: ‘in each case only one copy was available which the editor read standing on a bench in the laundry.’ Blythe recalled a play being performed, featuring John Gaskin himself, ‘about which the only thing I remember was that Kevin O’Higgins was one of the actors and that a lad named Gascoyne from Dun Laoghaire was also one of the players.’

Blythe also mentions that there was continuous practical joking in the prison, ‘all sorts of foolish and boyish tricks were played.’ One example given of this is ‘water-throwing’ in which Kevin O’Higgins participated and which caused ‘great annoyance to many other prisoners.’ Blythe finishes this anecdote by saying ‘I have a picture of a man being held down on the ground by four others while Kevin poured a large bucket of water over him, beginning at this head and going slowly down to his toes.’ These sorts of pranks, while funny to some, could be seen as bullying to others, and a difficult atmosphere to contend with if you’re on the wrong side of the fun. Not only do the prisoners have to be fearful of mistreatment from the authorities but also from their fellow inmates.

It is worth examining what sort of affect the revolutionary period, and in particular long stays in prison had on Irish republican soldiers. Post-traumatic stress, or ‘shell-shock’ as it was then known, was a feature of the post-war experience of soldiers who served during the First World War and veterans of the war of independence were not any different. Numerous testimonies show how hard the prison stays were for the men and women of the republican movement: conditions were poor, food was scarce and the treatment harsh.

The case of John Gaskin raises questions as to how such experiences impacted upon the mental health of prisoners. But can it offer an explanation for subsequent acts such as that perpetrated by Gaskin against Agnes Byrne? The Coroner at the inquest into Gaskin’s death acknowledged a possible link but ultimately left this question unanswered. He simply stated that ‘the deceased had apparently formed an attachment for her (Agnes Byrne), but his affection was not reciprocated. That and other matters must have affected his mind.’ The jury too expressed the view that the deceased was of unsound mind.

Agnes Byrne, 17 years-old and an enthusiastic Irish speaker and dancer, survived the attack on her life only with the help of a blood transfusion. More than a decade later, in October 1930, she married a man named Aidan Corish in the same Blackrock church that hosted the funeral mass of her attacker, John Gaskin.

Alyson Gray is a researcher and content producer for Century Ireland.