Football on Fire - The IRA war on Manchester City and United, 1920-21

By Mark Duncan

1.

It takes only a few names to make the point and you could spend an enjoyable, if non-productive, day arguing over those that do it best.

For anyone referencing Johnny Carey, George Best, Paul McGrath and Roy Keane, there’d be others, for certain, with a preference for Paddy Fagan, Mick McCarthy, Niall Quinn and Shay Given.

The point to be made is pretty straightforward: whenever the Irish influence on the sporting life of Manchester merits mention, the conversation will invariably turn to a roll call of players who have worn the blue and red of the city’s two principal football teams.

But there are broader histories of Manchester’s big two clubs where the Irish influence is perhaps less well known and where the relationship was shaped less by on-field sporting action than by the off-field and often volatile politics of the Anglo-Irish relationship.

Take the young Irishmen who were members of the Manchester brigade of the IRA and who, over the course of a five month period in the midst of the Irish war of independence, brought their campaign to two of the most iconic sports grounds in the north of England. Their targets were the stadiums of Manchester City and Manchester United and their aim was a singular one: burn them to the ground.

2.

Before there was the grand design and distinctive steel cabling of the modern Etihad stadium, there was the vast, concreted space of Maine Road. And before that again, there was the fragile, irregular structures of Hyde Road. Home to Manchester City Football Club, it passed for its time as state of the art and was considered ‘one of the finest football enclosures’ in England in the early 20th century. Hyde Road was by no means perfect, however.

Hyde Road, home ground of Manchester City. (Image: Yorkshire Evening Post, 13 April 1907)

Set in a dense, industrialised landscape, it was surrounded by railway lines, a boiler-works factory and rows of terraced housing that accommodated the working classes that had swelled the city’s population during the industrial revolution of the previous half century. The site was restrictive – too restrictive. Many decades later, interviewed by football historian Gary James, one old supporter reflected. ‘I always felt Hyde Road was homely. [However] we were always confined. Everyone looked after you but there wasn’t enough room.’

Despite renovations in the aftermath of City’s 1904 FA Cup success and later plans to redevelop the site to adjust the angle of the pitch and allow for the construction of a stadium that might hold 80,000 fans, frustration at delays and their dealings with unaccommodating neighbouring landholders led the club to search for alternative sites upon which to realise their grand ambitions. That search was effectively suspended for the duration of the First World War and it made little progress in its immediate aftermath.

By early 1920 the club still hadn’t found anywhere suitable.

Manchester City continued to play their football at Hyde Road, its cultural prestige and social significance to the north of England copper-fastened by the visit of King George V in March of that year – it was the first time a reigning Monarch had attended a soccer game outside of London, a mere sliver of football history that was nevertheless symbolic of the shifting class and cultural dynamics of post-First World War British society.

Just over seven months later, however, Hyde Road’s main stand had been razed to the ground, destroyed by fire. When the fire brigade arrived on the scene on the night of 6 November they found the stand ablaze from end to end. Within an hour it had fallen in on itself, reduced to a heap of flaming wood.

King George in introduced to Manchester City players at Hyde Road in March 1920 (Image: Manchester Guardian, 29 March 1920)

The timber stand wasn’t all that was lost. Incinerated with it were the club’s offices and an archival treasure trove, including books and ledgers that left the club scrambling to piece together its very own business affairs and struggling to re-establish contact with its own shareholders. The destruction at Hyde Road was presented as an unfortunate accident. The fire was believed to have started by a cigarette or cigar discarded during a match that had been held at the ground earlier in the day.

That was what newspapers reported at the time and it remains the story told today on the club’s official website.

But is it accurate? Was the inferno really the result of mere mishap?

In a book published in 2014 on the IRA in Britain during this period, the historian Gerard Shannon noted that the destruction of the Manchester City grounds was one of a number of incidents about which the police in Britain ‘suspected Irish involvement’.

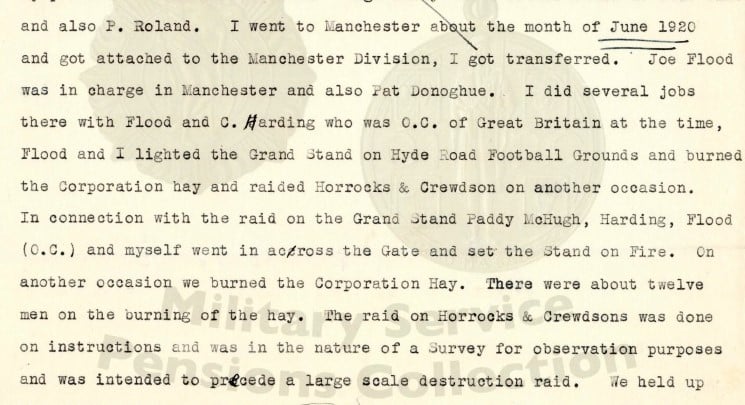

Those suspicions were well-founded – and not only because the fire fitted with a wider pattern of IRA attacks on British soil that had begun towards the end of 1920. Recent releases from the Irish Military Archives have also shed fresh and fascinating light on IRA activities in Manchester during this period. Among the deluge of correspondence and official forms is testimony from a former IRA Volunteer, Drogheda-man Thomas Morgan, who in 1939 began the process of applying for a pension under a scheme designed to recognise military service during the campaign for Irish independence. The pension scheme had been introduced by the fledgling Irish Free State government in 1924 and its eligibility criteria was greatly expanded when the legislation was modified a decade later. In all, more than 82,000 pension applications were received, assessed and processed. Thomas Morgan’s application was typical of the kind submitted, core to which were sworn statements outlining such services as were rendered to the cause of establishing the independent Irish state that was now evaluating these pension claims. In Morgan’s case, those services included the torching of the Manchester City stand.

Thomas Morgan provided little detail about how the Hyde Road operation was planned and executed, but his involvement in the attack was relayed to his pension assessors on the more than one occasion. He first admitted to the torching of the stand in October 1939 and did so again three years later in a further correspondence with the authorities. He also confessed to being one of a number of arsonists. In an initial question and answer exchange with the Irish pension authorities, he remarked that ‘...me and Harding and about 6 men ... took part in the burning of the Hyde Road football grounds.’ The only additional detail he proffered was that it ‘Hqrs (sic) of Manchester City Football. We decided we would burn the stands. They were preparing for a big match’. The ‘Harding’ referenced here was Charles Vincent Harding from Clonmel, who made no mention of the Manchester City attack in his own pension application, though he referred to his involvement in other IRA activity in Manchester at the time. This included the burning of a warehouse during which a police constable was shot in January 1921 and prior to that, in November and December 1920, a planned attack on Manchester Race Course and an actual attack – and arms raid – on a golf links. Another accomplice mentioned by Morgan was Joseph Flood who likewise made no specific mention of the Hyde Road burning, referring only in generalities to his war of independence service record. What this involved, he stated, was organising and taking an ‘active part in reprisal burnings in Manchester and district’.

Extract from the Military Service Pension file of Thomas Morgan where he refers to his involvement in the burning of the Grand Stand at Hyde Road. (Image: Military Service Pension Collection, MSP34REF19573 Thomas Morgan, Access the pension application file here)

3.

Thomas Morgan had joined the Irish Volunteer movement – what became the IRA – in May 1917 in his native town of Drogheda in County Louth. He belonged to a family of coachbuilders whose business slowed as Thomas’s links with Sinn Féin – along with those of his three brothers – deepened amidst the post-1916 Rising radicalisation of Irish political life. It was waning family fortunes that led him to set off for England in search of alternative work, but it didn’t take him long to resume his Volunteer involvement, first in Liverpool, and then, from June 1920, in Manchester.

Morgan had company aplenty in the IRA’s British ranks. The late Peter Hart, historian, estimated that in the 12 month period from the summer of 1920 to the summer of 1921 there were approximately 1,000 men involved in IRA units across the UK, most notably in the big urban centres of London, Liverpool, Manchester and Tyneside. More recently, Darragh Gannon has pointed to an even larger IRA membership, the numbers swelling, he suggests, to a peak point of 2,700 during this period. Of course, to be a member was not necessarily to be actively engaged with IRA operations. It didn’t translate automatically into a requirement for what many might consider to be active service. Even so, in Manchester, where the number of volunteers reached about 100, they were organised into three IRA companies, one of which – No. 2 Company – was led by Charles Harding, whom Thomas Morgan had claimed as an accomplice on the attack on Manchester City.

Up until late 1920, such operations as the IRA ran in Manchester were focussed on providing practical assistance to the republican separatist campaign back in Ireland. It took the form of fundraising at church gates and the procurement and trafficking of much needed arms and ammunition. There was also a propagandist dimension to it and in the aftermath of the police killing of Cork’s Lord Mayor, Tomás Mac Curtain, in his own home in March 1920, IRA volunteers in Manchester set about decorating the city with political graffiti, ‘Huns Murder Lord Mayor MacCurtain’ being just one of the messages painted.

By the autumn of 1920, however, there was a significant step-change in IRA activity in Manchester and other British cities. IRA actions increased in number and changed in focus. A campaign was launched that located Britain as a theatre of operations, the purpose of which was to make the IRA presence more widely and keenly felt. This strategic shift did not occur in a political or military vacuum: it was a calculated response to a violent escalation of the ongoing Anglo-Irish war.

Patrick O’Donoghue, officer commanding the IRA companies in Manchester at this time, recalled being summoned to a meeting in Dublin at which IRA responses to the deliberate burnings of Irish towns by crown forces were considered. Amongst those present was Michael Collins, a man of multiple roles – MP, Minister for Finance in the Dáil Éireann government and IRA director of intelligence. O’Donoghue knew Collins well (Collins had been best-man at his wedding to concert singer, Violet Gore) and had worked with him on various operations in Britain, including the remarkable jail-break of Sinn Féin president, Éamon de Valera, from Lincoln Prison in February 1919. After exploring possibilities for Volunteer activity in Manchester and English cities, the meeting took the decision to meet, often literally, fire with fire. Manchester and other cities were to be targeted with the principal purpose of raising public awareness of Ireland’s desperate and worsening predicament. As O’Donoghue later recalled:

‘It was felt that the people in England should be made conscious of what the people in Ireland were suffering as regards depridations carried out by the crown forces. And it was to be definitely understood that any burnings the I.R.A. might carry out in Manchester would not be solely for the purpose of reprisals but merely to bring home to the British people the sufferings and conditions to which the Irish people were being subjected by their police and soldiers here.’

The burnings began not in Manchester, but in Liverpool. On the night of 27 November 1920, the Saturday following the horrors of Bloody Sunday in Dublin and the eve of the Kilmicheal ambush in Cork, up to 18 separate fires were started in cotton warehouses and timber yards in the Liverpool and Bootle dock areas. The damage was extensive: some properties were destroyed completely and a price-tag of between £750,000 and £1m was put on the destruction caused. But the damage was as much psychological as physical or material. A fear that Irish republicans would turn their attention to the London citadels of British political power led to barricades being erected outside Downing Street and the imposition of restrictions on access to the houses of parliament. Back in Liverpool, meanwhile, steps were taken to secure banks and important public buildings against further arson attacks. The Daily News observed ominously that the fires in Liverpool provided the ‘first indications of Irish crime beginning to raise its ugly head in this country’.

Deploying arson as an instrument of war involved no new departure, however.

It had been widely and effectively in the Irish guerrilla campaign already. It had been used in attacks on isolated rural police barracks and had helped force a retreat of the British state in Ireland, beginning in mid 1919. Over the course of the following Easter weekend – in April 1920 – some 218 police barracks and huts were targeted for torching, as were 21 tax offices across the country. Yet incendiarism was not the preserve of Irish separatists alone. It was even more devastatingly deployed as a weapon of British reprisal from the Spring and Summer of 1920 onwards when Ireland’s depleting police force received an injection of new recruits in the form of the so-called Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries (Auxiliary Division of the RIC), the former drawn from ex-First World War servicemen and the latter from decommissioned officers whose mission was to act as a crack counter-insurgency corps.

Poorly trained, ill-disciplined and completely unsuited to a policing role, the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries soon established a reputation for heavy-handedness and worse. Their notoriety was well-earned. It wasn’t just that they were implicated in cases of looting or harassment – it was the indiscriminateness with which they targeted the civilian population that elicited the fear and public opprobrium. In September 1920, the north Dublin seaside village of Balbriggan was visited by the Black and Tans who killed two civilians and burned much of the town in reprisal for the shooting dead of a Head Constable. They followed this by inflicting something similar on the Meath town of Trim a few days later, though the policy of reprisals would not reach its nadir until December when large parts of Cork city centre was destroyed by fire. That same month, the Labour MP Arthur Henderson, who led a commission of investigation into conditions in Ireland, denounced the practice of reprisal in emphatic terms. ‘Things are being done in the name of Britain which must make her name stink in the nostrils of the whole world’, he said. ‘The honour of our people has been gravely compromised’.

The very policy that gave rise to this British MP’s sense of affront was the same policy that gave rise to the decision to launch the IRA campaign in Britain in late 1920. And as outrage begot outrage, the Manchester Guardian was moved to observe the grim spiral where ‘violence on one side answers automatically to violence on the other’. This destructive trajectory continued into the early months of 1921 and though its consequences were most acutely and extensively experienced in Ireland, they were felt too in Manchester.

4.

The distance from Manchester City’s home ground on Hyde Road to Old Trafford was no more than 8 kilometres (5 miles).

It was there, to the south west of the city, that Manchester United had built their new stadium in 1910, having taken the decision to abandon their previous home on Bank Street when it was deemed ill-suited to expansion.

If the move across the city took Manchester United away from its original working class support base, it had the advantage of delivering them a new 80,000 capacity stadium. It was designed by Archibald Leitch, the Scottish engineer who would become synonymous with the sporting architecture of early and mid 20th century Britain. Leitch designed stands at approximately 17 English football grounds between 1903 and his death in the late 1930s, his influence straddling the Irish Sea when he added stands and terracing at Windsor Park in Belfast and Dalymount Park in Dublin to his then already impressive architectural portfolio.

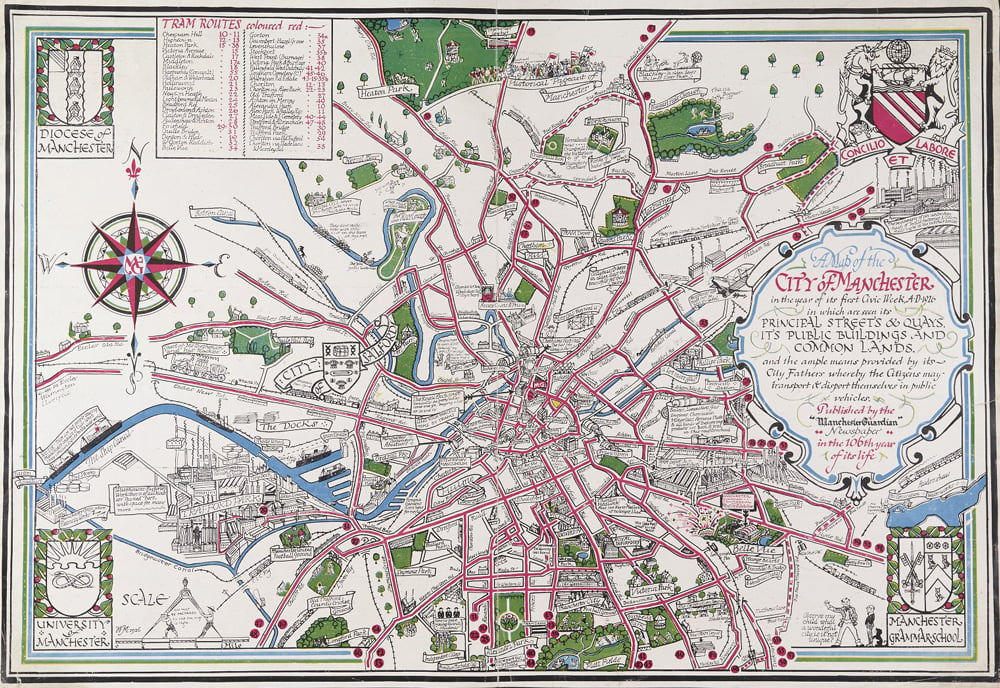

A map of Manchester which was published in a colour supplement to the Manchester Guardian on 2 Oct. 1926. Featured on the map are the locations of the city’s principal football stadiums at the time, Manchester United's home ground of Old Trafford and the Maine Road ground to which Manchester City moved after they vacated Hyde Road in 1923. (Image: Manchester Archives and Local Studies, GB127. Local Studies Street Map Collection/19)

Leitch’s designs were simple and utilitarian.

What they lacked aesthetically, they more than made up for in straightforward functionality. Ensuring sightlines while maximising spectator access were what mattered most. The stadium at Old Trafford did just that by providing a single covered stand with seating that was adjoined to open terracing on the three sides of the playing pitch. It’s impressive scale was such that within a year of opening it hosted the 1911 FA Cup Final replay and it was chosen again as cup final venue in 1915, the only one played during the First World War and recorded in history as the ‘khaki final’ owing to the large attendance of uniformed soldiers. In March 1921 Old Trafford was again being utilised by the Football Association (FA) to host a major cup-tie. It was not a final, but a mid-week meeting of Wolverhampton Wanderers and Cardiff City in a cup semi-final replay. It was close to midnight on the night before the fixture, 22 March, when a small group of Irishmen visited the venue with the intention of burning it to the ground.

They were by then, as their own subsequent testimonies would attest, already practised arsonists.

Thomas O’Brien, a Limerick-native, had been involved in the burning of farm houses and hay before graduating to setting fires in a cafe and hotel in Manchester. Of the latter, O’Brien recalled: ‘We went and booked bed and breakfast and piled up the furniture – the whole lot of them went up together at 6 o’clock in the morning.’ Peter J. Gilmartin had been involved in raids for firearms and the burning of a stores and warehouse in Manchester in late 1920. He also claimed to have been a member of an IRA party that had ‘burned many rooms at the Central Hotel’ in the city in January 1921.

Paddy Fennell had likewise been busy. ‘A good, active man’ according to an ex-colleague who supported his pension application, he held the rank of First Lieutenant in the 2nd Battalion of the Manchester IRA, joining soon after his arrival in the city from Tipperary in early 1919. Fennell had been initially tasked with gathering arms and ammunition for ‘shipment to Ireland’, but from late 1920, he claimed to have been ‘in charge of the burning of certain buildings including Queen’s Park Museum, Halloween Wood Mill Factory and various hay barns etc etc in and around Old Trafford.’

When O’Brien, Gilmartin and Fennell – together with Michael Hayes and Eamon Conroy – approached the home ground of Manchester United, they did so under the cover of darkness. It was not enough for them to go undetected, however. Constable Thomas Carr of the Lancashire County Constabulary was working that night at Glover’s Cable Works in Trafford Park, which was situated beside the football ground. When Carr climbed a ‘slag heap’ to peer over a wall into the stadium, he discovered three men in the enclosure of the ground (there were also ‘two outside men’ of which 23 year-old Paddy Fennell was one) and decided to verbally challenge them. The startled IRA men responded by firing two pistol shots in the Constable’s direction. As Thomas O’Brien recalled it, ‘one of our chaps got excited and there was a guard there and he fired on the guard and the guard fell and we decided to clear off then.’ Constable Carr slipped and fell down to relative safety of the bottom of the slag heap, while the IRA arsonists took flight, one of them, Eamon Conroy, who ‘carried firearms’ on the raid, injuring his ‘right ankle and limb’ as he fled.

A search of the Old Trafford ground soon revealed to the police the character of what had been planned and by whom. Three bottles of paraffin were found for a start. So too was a small pocketbook. It belonged to Paddy Fennell and it contained an infirmary ticket that led to his prompt arrest at an address at Bedford Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock, the following day – 23 March. The certificate with Fennell’s name on it wasn’t the only key item found in his wallet, however. Alongside it was what the staunchly unionist Belfast News Letter described as an ‘amazing document’ that was typewritten and headed, ‘Deserters from Ireland’. The document stated that the government of the Irish republic – established in January 1919 by popular mandate if not with international recognition – had issued permits to allow persons to leave the Irish territory and it claimed a similar right to permit emigrations. Certain persons, the document continued, had left Ireland without permission as either ‘deserters from the Volunteers or fugitives from the Republic’ and had crossed to England or Scotland. ‘You will take steps’, the document instructed’, to see that the matter is generally known, and that such persons will be treated properly as deserters.’

If this document was a clear pointer to Fennell’s political loyalties and connections, so too were the Sinn Féin ‘badges and emblems’ found in his possession at the time of his arrest.

Fennell was promptly hauled before the Manchester County Police Court. ‘I dare say you know’, the prosecuting counsel told the court, ‘that there is a big football match at this ground this afternoon, and there is no doubt that these men were present for a very wicked purpose.’ While that purpose was undoubtedly incendiary, this was not the charge that was levelled against Fennell. Instead, the charge he – along with two others not in custody – faced was that of being in possession of firearms and attempting to murder Constable Thomas Carr. The case would not come to trial until July and wasn’t decided until shortly after a truce in the Anglo-Irish war had been declared. Fennell – whose defence team included the Nationalist MP for South Down, Jeremiah McVeagh – denied the charge of attempted murder and provided an alibi as to his whereabouts on the night in question. Not only that, Fennell was fortunate enough to have a witness willing to place himself in his, Fennell’s, place at Old Trafford on the night of the shooting. That witness was Charles Harding, one of the men responsible for the torching of the Hyde Road home of Manchester City the previous November as part of the same IRA campaign in the city. Harding, a 21 year-old mechanic, was by then serving a 15 year sentence and had to be brought to the courthouse from prison. The court was told that Harding had met Fennell at a popular Irish club on Manchester’s Erskine Street on the night of 22 March and had borrowed his coat. While Fennell, it was claimed, had then gone to a pub and then to his sister’s house before returning home to his lodgings, Harding and two others he named as John (Sean) Morgan and J. Barrett headed for the Old Trafford football ground. From the witness box, Harding said they had scaled a wall 12 feet high by standing on each others’ shoulders and affixing a rope. When disturbed by Constable Carr, Harding said that he had moved in the policeman’s direction and had only fired at the Constable after he had himself been fired at. Harding insisted that the shot he fired had not been intended to harm the officer, but to frighten him sufficiently to afford the IRA men an opportunity to escape. In saying that, Harding remained unrepentant about the IRA’s targeting of Manchester United. ‘We carried this out that night as a reprisal for the burning of our homes in Ireland and I maintain that it was my right to do so.’

While Harding’s political convictions were unquestionable, the same could not be said of his evidence in court.

Despite his eagerness to accept responsibility – ‘If you want the right man, put me in the dock’ – there was too much that was convenient about the testimony he provided. Harding himself was already serving time, Morgan was dead and Barrett was back in Ireland, so while the story he told might help free Fennell, it was essentially consequence-free for everyone else. Constable Carr also cast doubt on its veracity. For a start, he denied ever firing a shot; indeed, he claimed to have never fired his revolver in his life at all. The constable was also certain as to Fennell’s identity, claiming under examination that he had a clear sight of the IRA men as there was ‘an arc light shining in their faces’ – a detail previously omitted on the grounds that, he says, he had never been asked. In the end, while the judge – Justice Rigby Swift – assumed that Fennell had not been the one to fire the shots at Old Trafford, the jury found him guilty. The sentence handed down was seven years penal servitude.

5.

The foiling of the Old Trafford arson attack and the arrest and imprisonment of Paddy Fennell was not the only misfortune to befall the Manchester IRA in early 1921.

Within weeks of the attempted burning of the Manchester United stand, they would suffer a far more severe setback when police raided the Irish Club on Erskine Street in Hulme. This was the place that Charles Harding was supposed to have met Paddy Fennell prior to heading to Old Trafford and it sat at the centre of Irish revolutionary activity in the city of Manchester. Ostensibly a social venue which served as a meeting place for Irish people in the city, the Erskine Street club was also, a subsequent court hearing was informed, ‘a base of operations’ where IRA activities in Manchester ‘were planned and from which they were carried out’.

This was no baseless allegation. It was here after all that No. 2 Company of the Manchester IRA was headquartered and where the Irish Self-Determination League had its base. It was here, too, that Eamon Conroy, who participated in the Old Trafford attack and shared a workplace with Paddy Fennell, had been sworn into the IRA in the summer of 1920. And it was here on the night of 2 April 1921 that Conroy stood on armed ‘scout duty’ – a regular service he performed at the club – when armed police came calling.

What brought the police to the Irish club was a wave of incendiarism across Manchester in the early hours of that morning.

Fires had been started at hotels, warehouses and a cafe and there was little doubt in official circles as to who had ignited them. At the State Café, Piccadilly, where petrol had been emptied over a pile boxes and set alight, one of the four men responsible had paused to proclaim, in a ‘strong Irish brogue’, to the huddled, on-looking staff: ‘We are doing this because you are doing it in Ireland.’ Here, as with other locations visited, the damage to property was not significant, though a police constable – William Boucher – was hospitalised when shots were fired after he interrupted arsonists at Bridgewater House, a recently built packing warehouse.

The police response to the morning’s events was not an immediate swoop on the Erskine Street Irish Club. Indeed, by the time that Sergeant Crowther and three other policemen approached the club the day was nearly done. It was 10.30 pm and the club was by then heaving with activity – and not of the political kind. This was a Saturday night and a whist drive and a dance had helped draw a big crowd of weekend revellers. As with many similar incidents during the war of independence, no single narrative exists as to what happened next. According to one account, a ‘miniature battle raged for about a quarter of an hour’ during which shots were fired – by whom exactly would be a source of contention – and a number of the policemen were injured. Injured too was Frank McGurk who was hit by three bullets in the leg, while 23 year-old IRA man Sean Wickham ended up hospitalised after being wounded in the jaw. The one fatality was also an IRA Volunteer: 25-year old Sean Morgan was shot dead by police and buried the following week in a coffin ‘shrouded in the tricolour’. In death, this same Sean Morgan would be conveniently, if implausibly, identified by Thomas Harding as an accomplice in the attack on Old Trafford when gave evidence in the court case against Patrick Fennell.

When the shooting ended and the excitement abated at Erskine Street, police reinforcements conducted an extensive search of the premises and turned up no end of incriminating evidence – inflammable materials, revolvers and Sinn Féin documents. On foot of the raid, indeed, the police were able to arrest ‘practically the entire No. 2 Company’ of the Manchester IRA. Absent from them was Peter Gilmartin, a participant in the Manchester United raid who in his pension application claimed also to have gone – with two others – to Aintree race course in March 1921 for the purpose of shooting ‘King George V when he would appear on the balcony as the Grand National race was run.’ Gilmartin was in the Erskine Street club when the police raided, but took advantage of the ensuing commotion to flee the scene, taking flight to Dublin where he stayed only briefly before returning to England to resume his IRA activities in Liverpool.

About 19 people in all were arrested during or soon after the Erskine Street raid.

Manchester IRA members photographed in February 1922 following their release from prison. (Image: Military Service Pension Collection)

They did not stand trial immediately. Instead they would have to wait until July 1921, their case overlapping with Patrick Fennell with whom they shared the same trial judge – Justice Rigby Swift. These trials were a major event and attracted much publicity on either side of the Irish Sea. The exclusion of the general public and the heavy, armed police presence outside the Manchester courthouse was a measure of the seriousness with which the authorities viewed the case. So too was of the presence of the Attorney General Sir Gordon Hewart, who led the prosecution of those rounded up after the Erskine Street affray and sought to make use of the Treason Felony Act of 1848, which had been used to transport fenians such as John Mitchel to Australia in the aftermath of the revolutionary upheavals of that year. Making his opening contribution, Hewart, who would later that year become a signatory of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, told the court that in order to prove the charge of treason felony the accused should be shown to have had the intention of deposing the King or to levy war on the country and ‘the facts in this case showed fully those intentions’.

In making this case stick, the prosecution was sensationally helped by the decision of two members of Manchester IRA’s No. 2 Company to turn King’s evidence. To become what 34 year-old Patrick O’Donoghue, IRA leader in the city, would call ‘informers’. O’Donoghue was somewhat forgiving of one of the two men – 17 year-old Daniel McNicholl – whom he believed had been responsible for his own arrest and who was, he suggested, ‘little more than a lad at the time’ and ‘probably frightened into it.’ The other volunteer turned informer was Charles Murphy, called by the prosecution as their first witness. Previously a member of the Irish Volunteers in Belfast, Murphy had only been a member of No. 2 Company for a matter of weeks and had not, Patrick O’Donoghue would subsequently claim, been given ‘sufficient recommendation for his admission as a member’. For Michael Collins, the hasty admission of Murphy had been a ‘positive disgrace’ that reflected badly on the Manchester IRA. What Murphy told the court was exactly what the prosecution wanted to prove – that there had been a conspiracy. Murphy had been at Erskine Street on the night before the arson attacks of 2 April and he identified Charles Harding as the ‘captain’ who received and passed on the order to ‘fire hotels and warehouses’. He told how it was Harding who had instructed eight men to book hotel accommodation, while eight more, armed with loaded revolvers, remained at the Erskine Street club before joining them the following morning.

The trial ran for a week exactly and straddled the conclusion of the Anglo-Irish truce. Indeed, the Irishmen were in the dock at the hour the truce came into effect and Patrick O’Donoghue made sure the moment was properly marked, giving the Judge ‘a terrible shock’ when, as the clocks struck midday, he issued an instruction in Irish that led all the accused men to leap to their feet and ‘salute the Truce’. O’Donoghue, for his part, denied involvement in the shooting of Constable Boucher when fires were being started at Bridgewater House, but he told the court that the truce had reaffirmed his belief that he had being doing his moral duty in smuggling arms to Ireland. ‘The events of the past few weeks have completely justified my contention’, he declared in a closing statement from the dock. ‘The armistice entered into by Mr Michael Collins, commander-in-chief of the Irish Republican Army, on the one side, and General Macready, on the other, is a tacit admission that a state of war existed in that country up to July 11.’ The attorney general, leading the prosecution, was dismissive of this line of reasoning. The truce, he rejoined, was an admission of nothing. What had been brought about was a ‘truce of murder, a truce of killing, a truce of crime. It is one thing to suspend crime; it is another to suspend the criminal law.’ Pressing this point, Sir Gordon Hewart impressed upon the jury that what was happening in London was irrelevant to the determination that they should make.

For many of those standing trial, the jury’s deliberations held little prospect of reprieve and, for most, none was forthcoming. Two of the charged men were set free, but the guilty verdicts for the others brought sentences that ranged from three to 15 years of penal servitude. 17-year-old Daniel McNicholl, who had given evidence against many of the accused, was given the lightest three year sentence and asked to see his mother before being led to the cells. Michael Hayes and Thomas O’Brien, both of whom had participated in the attempted burning at Manchester United, received sentences of five and seven years respectively, while those at the receiving end of the heaviest ‘treason felony’ sentences were Patrick O’Donoghue and Charles Harding, both of whom were sentenced to 15 years penal servitude along with Shaun Wickham who had been shot and wounded at Erskine Street. Seated beside each other as their sentences were being read out, these three men – O’Donoghue, Harding and Wickham – smiled and shook hands as the courtroom gallery, now open to the public and brimful with sympathetic supporters broke into supportive shouts of ‘Three cheers for the Irish Republic.’ The commotion caused led police to forcibly remove from the court many of those doing the shouting – mostly women and relatives of the guilty men.

6.

The sentences handed down in Manchester were not the sentences served.

The convicted men were led from the court and scattered across different prisons in England where they were deliberately kept apart from other Irish prisoners. However, all would benefit from a general amnesty that led to the release of Irish political prisoners in the wake of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

Abbreviated though it was, the jail time served by the convicted Irishmen in Manchester was neither easy nor without lasting effects. When applying for a ‘wound pension or gratuity’ in the early 1930s, Charles Harding would complain that his physical frailties – gastritis and neurasthenia – and his inability to work – he considered himself unsuitable to the ‘present methods industry’ – had stemmed from ‘forcible feeding and rough treatment’ during his short term of imprisonment. While Harding’s pension assessors were unconvinced of such cause and effect, his point was not an isolated one. Other veterans of the Manchester IRA – and of the attacks on the city’s principal football grounds – would draw similar connections between their revolutionary experiences and later infirmity. Submitting his pension application from the United States, to where he’d emigrated in 1923, Paddy Fennell, the only person convicted of the Old Trafford attack, claimed that that it was as a ‘direct result’ of his ‘incarceration and hunger strike’ that he had contracted rheumatism and arthritis which had ‘ almost wholly incapacitated’ him. ‘I am unable to write at times but can manage to sign my name’, he informed the pension authorities. Michael Hayes who had been with Fennell at Old Trafford suffered similarly from rheumatism and decades later complained that it was the reason he was ‘no longer able to work’, adding acidly that there were men drawing pensions ‘who never gave a night out of bed’.

A Dept. of Defence pension cheque to Michael Hayes records his death in 1981 (Image: Military Service Pension Collection, MSP34REF59188 Michael Hayes. Access the pension file here.)

More generally, the afterlives of those who participated in the Manchester IRA campaign reflect the diversity of the revolutionary generation’s post conflict experiences. While some made stable, even relatively prosperous, lives for themselves in Ireland, others struggled or felt compelled to seek futures outside of the country whose independence they had helped secure. Joseph Flood, who along with Charles Harding and Thomas Morgan, had participated in the burning of the Hyde Road stand, was among the latter. After exhausting the proceeds of the sale of his family farm in Cavan, Flood and his dependents had ended up surviving on outdoor relief programmes, first in Dublin and then in England. As to the reasons for his reduced circumstances, Flood was in no doubt that that his service to the separatist struggle was to blame. He had, he alleged, ‘suffered severe financial loss through my activities and was dismissed from executive posts’ when his identity and past became known. In 1934, having returned to England from Ireland, Flood claimed that his ‘future’ and that of his family seemed ‘doomed’ and more than 20 years later, in a further exchange with the pension authorities, he wrote from his Basingstoke home of being ‘paralysed through accident and am compelled to a wheel-chair existence.’ Flood’s personal hardships contrasted with that of Patrick O’Donoghue, who provided statements in support of many of the Manchester IRA pension applicants. Older and better-off than many of the men he was convicted alongside in Manchester in July 1921, O’Donoghue would fare well in the new Ireland that emerged out of the revolution, entering the licensing trade before turning his entrepreneurial talents to sport, where he helped establish and grow greyhound racing as both an industry and an outlet for popular entertainment.

Greyhound racing commenced in Ireland in 1927 and it is likely that those behind its emergence were influenced by developments in the city where O’Donoghue had previously lived, worked and pursued his revolutionary politics. When Ireland’s first greyhound tracks were launched at Celtic Park in Belfast and Shelbourne Park in Dublin, they followed closely on the pioneering example of Manchester’s custom built, oval track at Belle Vue stadium, which had opened the previous year. In Manchester, as in Ireland, greyhound racing would enjoy a sudden surge in popularity, but it never threatened to eclipse the mass spectator appeal of the city’s principal sporting passion.

That remained football. And in the aftermath of the IRA attacks on their respective stadiums in 1920-21, the two big Manchester football clubs continued about their business without missing a step. Within a week of the burning of Hyde Road’s main stand, Manchester City were back playing at the ground, the charred debris having been cleared away and a ‘terracing of earth’ created where the timber structure had previously stood.

But if the arson attack did not put a stop to the football, it did add a greater urgency to the search for a new club home. Eventually, they found one. Manchester City would play their last league game at Hyde Road in April 1923, not long before the Irish civil war – the internecine conflict to which the independence struggle had given way – would finally draw to its close. The club would soon take up residence on Maine Road at a new stadium that delivered everything that Hyde Road couldn’t – space and scale. It would become known as the ‘Wembley of the north’.

Mark Duncan is a director of Century Ireland.