Flying into history – Ireland & the story of the first Transatlantic Flight

By Prof. Mike Cronin

On 17 December 1903 Orville Wright piloted the world’s first powered airplane in a successful flight. Above a windswept North Carolina beach, Wright flew the plane at a height of 20 feet and for a mere 12 seconds. In all the plane covered a distance of 120 feet in the air.

From such rudimentary beginnings it was remarkable that 16 years later John Alcock and Arthur Brown made the first successful transatlantic crossing by air. Compared to Wright’s brief flight, Alcock and Brown flew non-stop for over 14 hours and travelled 1,890 miles from Newfoundland to Clifden in County Galway.

One of the major reasons for the rapid development of air transport was the outbreak of the First World War. In 1913, shortly before the outbreak of the war, the Daily Mail had offered a prize of £10,000 for a successful air crossing of the Atlantic in under 72 hours. While the prize was substantial, aviation technology was not yet developed enough that anyone but the foolhardiest would even try and tackle the crossing. Both the British and the Germans saw the military advantage of planes during the First World War. First for reconnaissance purposes, and later as fighting machines. Given the military demands for efficient and effective aircraft, plus the deep pockets of both countries, aircraft technology developed quickly and became far more dependable (although still highly dangerous) between 1914 and 1918.

A commemorative cover from Flight International magazine to mark the 25th anniversary of Alcock and Brown's flight. It draws parallels between their journey and the one taken by Christoper Columbus in 1492 (Image: Flight International, 15 June 1944)

Both Alcock and Brown (the former a pilot, the latter an engineer and navigator) had flown in the Royal Flying Corp during the First World War. During the war a plane Alcock was flying in crashed over Turkey, while Brown was shot down over Germany.

Both men were German prisoners-of-war until their release in 1918. Alcock would often tell the story that the dream of flying the Atlantic came to him while he was a prisoner. After he had returned to Britain he made contact with the Vickers firm and was appointed their pilot for the transatlantic challenge. He would later meet Brown who, although unemployed at the time, was hired as navigator for the challenge due to his skills and the extensive number of flying hours he had under his belt.

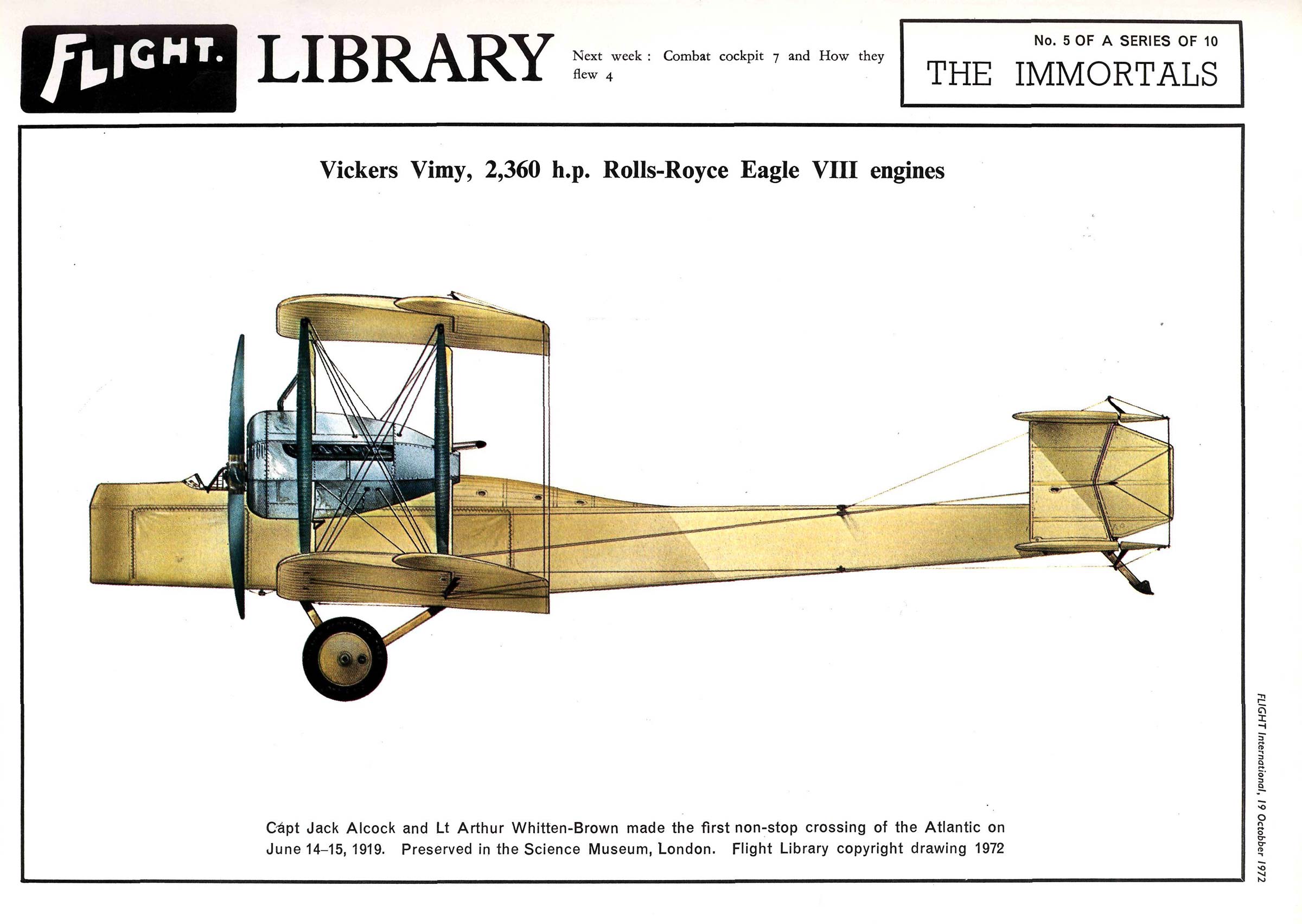

The Daily Mail contest to fly the Atlantic had been suspended during the war, but was opened up again in November 1918. The summer of 1919 duly brought a number of teams to Newfoundland to attempt the crossing, and Alcock and Brown departed, flying their Vickers Vimy, in the early afternoon of 14 June. On board alongside the two men was a package of mail for delivery, 3,900 litres of fuel, an electric generator to power the radio and provide heat, and two toy cats as lucky mascots. Shortly after take off the generator failed which meant that the two men had no heat in their open cockpit and, critical in such an endeavour, no functioning radio or intercom.

In effect they would have to fly the whole way without heat, and no way of talking to the ground or, perhaps more importantly, to each other.

Across the Atlantic they were hampered by thick fog, and in the early morning of 15 June they flew through a heavy snowstorm. So rudimentary was the technology for this flight that the weather was critical. In fog and snow Alcock’s vision was impaired. Given that they were relying on readings from a sextant to offer them direction, such poor visibility left the men effectively lost above the Atlantic through the night.

On the morning of 15 June, Brown finally spotted the western coast of Ireland. While there had been plans to fly onto London, the men decided that it would be safer, because of poor weather, to attempt a landing on the seemingly flat green land of Derrygimlagh bog which lay just outside of Clifden. The bog was an important target for Alcock and Brown. Not only did it look like a basic landing strip, given its grassy appearance, but the bog was also the home of the Marconi Wireless and Telegraph Station that sent and received messages crossing between Europe and the United States. If their landing, and hence their crossing of the Atlantic was successful, then the news could be spread across the world by the Marconi staff almost instantly.

Brown (left) and Alcock (right) in the Automobile Club on Dawson Street, Dublin, after arrived from Clifden. Note the cat mascots: one on Alcock's lap and the other on the cushion between the pair (Image: Irish Life, 20 June 1919. Full collection available in the National Library of Ireland)

At 8.40 in the morning Brown brought the plane into land. He mistook what he thought was flat grass for his landing area, and instead brought the plane to a halt on the bog and the historic first crossing of the Atlantic ended with the Vickers upright, its nose buried in the soft bog of Derrygimlagh. As planned, the word of their success was telegraphed around the world, and journalists from across Ireland and beyond sped to Clifden to interview the two men. In the event Tom Kenny of the Connacht Tribune arrived first, and got the biggest interview of his career. Celebratory telegrams were received from Downing Street and Buckingham Palace and, from Rolls Royce (the makers of the engine that had got them across the Atlantic) cases of champagne arrived which were drunk at an impromptu party that night in Clifden.

On the morning of 16 June, Alcock and Brown, the news of their historic crossing and a previously unknown bog in the west of Ireland were front page news across the world. The landing point that signalled their successful crossing is now marked by a memorial in the bog, and the feat of Alcock and Brown placed Ireland in a central role for the future of transatlantic aviation. The first east-west crossing of the Atlantic took place from Dublin in 1928, and featured Irishman Colonel James Fitzmaurice as one of the three-man crew. From the late 1930s Foynes functioned as the Irish base of the transatlantic flying plane fleet and, from the late 1940s Shannon airport was the stopping off point for all passenger planes, irrespective of their departure point in Europe, from the journey to North America.

Alcock and Brown were rightly hailed as heroes in 1919. Their successful flight was a testament to their skill, but also a product of how rapidly aviation had been developed during the years of World War One.

From the time of their landing in the west of Ireland onwards, the country would play a key role in the history of 20th century aviation. The Alcock and Brown flight was a remarkable feat and one, given that news from Ireland at the time was dominated by reports of the fighting in the War of Independence, gave the world an alternative and perhaps more uplifting view of the country.

Professor Mike Cronin is Academic Director at Boston College-Ireland and a Director of Century Ireland