FEATURE - The Amritsar Massacre, 13 April 1919

By Dr. Kate O’Malley

In February 1920 in New York, Éamon de Valera was a key note speaker at a ‘Friends of Freedom for India’ gathering in the Central Opera House, which, according to reports, was jammed to the rafters. His talk was titled ‘Ireland and India’, and in it he referenced Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, later dubbed ‘the Butcher of Amritsar’, no less than five times. The speech was published in pamphlet form, sold for 25 cents, it received extensive press coverage and its circulation was banned in India.

The aftershocks of what became known as ‘the Amritsar Massacre’ were acutely felt a year later. They rumble on still as its centenary approaches with a row erupting over a bid to extend Britain’s centenary events to cover Ireland and India. Extending the commemorative programme to include these fateful moments on the peripheries of the British Empire would surely have de Valera’s approval.

The frontispiece from the published version of de Valera's speech on Ireland and India. To view on the Internet Archive website click here (Image: Internet Archive)

So what is the background to the Amritsar massacre?

In the wake of the First World War the government of India tried to introduce a set of controversial measures known as the Rowlatt Bills, which would give the authorities special powers to deal with what was viewed as increased sedition on the part of nationalist activists. In the interim the authorities used the Defense of India Act (1915) to extend draconian emergency powers into peacetime. Gandhi, who had only returned to India a few years earlier, declared a ‘stayagraha’ (non-violent protest) and ‘hartal’ (boycott) campaign in opposition to these measures. This unique form of peaceful protest attracted, for the first time, the rural, unrepresented masses of India. However, as momentum built, keeping control of the movement became impossible and, in the Punjab, tensions ran particularly high. The province was a traditional recruiting ground for the Indian army and as a result, had a significant European presence in its ‘Civil Lines’.

By 1919 tens of thousands of Punjabi men had returned from fighting in the First World War and now faced economic hardships at home. The prospect of increased autonomy that appeared on the horizon as a result of the Montagu Chelmsford reforms was immediately dashed with the announcement of the Rowlatt Bills and their accompanying repressive measures. There were geo-strategic factors at play too, the Punjab bordered Afghanistan and, in the Spring of 1919, there were growing concerns after the coming to power of the Emir Amanullah Khan (the third Anglo-Afghan War would break out that May).

Rioting soon broke out and the authorities immediately grew concerned especially after the deaths of five Europeans and the treatment of an English missionary school teacher, Manuella Sherwood, who was grabbed off her bicycle and severely beaten. In the days that followed the infamous ‘crawling law’ was instituted whereby Indians had to crawl on all fours past the spot where the attack had happened.

The actions of two men, both with connections to Ireland, were pivotal in the events that unfolded; General Michael O’Dwyer, Lieutenant-Governor of the Punjab, and the local military commander Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer. A Catholic from a large Tipperary family, O’Dwyer had been serving in India since 1885. As a loyal Irish servant of the crown (there were many serving in India at this time, it was an attractive proposition for ambitious young men) he said he was disturbed to hear of ‘the terrible events that had been going on in Ireland since the Easter Day rebellion.’

Dyer however was born in the Punjab, his father had opened a Whiskey distillery in the hill station of Murree in 1860. Dyer was sent back to Britain and Ireland for his education and went to Midleton College, Co. Cork before attending the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.

From Dyer’s perspective the unfolding events in the Punjab early that April were reminiscent of his acquired memories of the days leading up to the Indian Mutiny/First War of Independence of 1857, and his growing sense of paranoia punctuated his reckless actions.

LISTEN: Myles Dungan is joined in studio by historian Kate O’Malley, editor with the Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy series.

On 10 April in the wake of the successful satyagraha in Amritsar two of the main organisers, Saifuddin Kitchlew and Satyapal, were arrested.

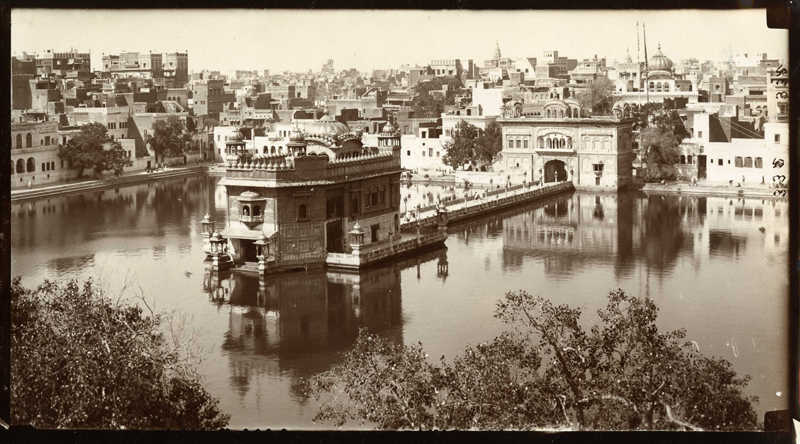

On April 12, although calm had been restored, Dyer issued a curfew and banned all public meetings. Word reached him the following day that a large group of people had gathered in Jallianwala Bagh, a walled public enclosure close to the Golden Temple which had only one entrance along a narrow lane. Although most of those gathered were part of the satyagraha campaign, many villagers had also congregated there to celebrate the Sikh festival of Baisakhi. Those from the rural surroundings would have been unaware of the hastily announced proclamations the previous day.

Dyer and ninety of his troops marched to the area to disperse the unlawful gathering. Remarkably, without any warning, he ordered his men to start shooting at the 20,000 strong gathering of unarmed men, women and children, who had no way of gaining cover or exiting the enclosure. The shooting continued for ten minutes and 1,650 rounds were spent. It is important to note that the official figure of 379 dead has always been disputed, and this is hardly surprising given that the forces turned and walked out; the dead left uncounted, the dying and injured left unaided.

O’Dwyer’s support of Dyer’s actions was forthright and immediate. He maintained this backing even after word had gradually spread outside India of Dyer’s brutal actions and a commission of investigation had been set up, the Hunter Commission. Its findings were damning but it did not impose any penal or disciplinary action on Dyer because of the support of his superiors, like O’Dwyer. Dyer’s recent promotion was revoked, and he resigned the following year. There was immense support for Dyer from both the British community in India and at home in England. The Morning Post opened a public subscription for him which raised £26,000.

However, on the ground in India things would never be the same and it was a turning point in the country’s history. The brutality that was unleashed that day had an immeasurable impact in the years that followed and on the nationalist movement in general. Events in Amritsar brought in their wake the successful non-cooperation movement and saw the emergence of Gandhi as a force in Indian politics. In the wake of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre Gandhi asked, how could they possibly compromise when the British Lion ‘shakes its claws at us?’

In his New York talk de Valera was even more critical: ‘Dyer had to shoot the people of India else the British Empire could not endure in India,’ he said. Dyer’s actions would ultimately have the opposite effect. In the years that followed Indian activists were more united than ever behind Gandhi’s campaigns of civil disobedience and non-cooperation, which ultimately resulted in Indian independence in 1947.

Dr. Kate O’Malley is Managing Editor of the Royal Irish Academy's Dictionary of Irish Biography (DIB)

Twitter: @KOM_acc