Explainer: The Kilmichael Ambush

By Mark Duncan

What was the Kilmichael Ambush and was it militarily significant?

On 28 November 1920, exactly a week after the events of

‘Bloody Sunday’ in Dublin, the West Cork Brigade of

the IRA ambushed a police patrol near the village of Kilmichael,

12 kilometres south of Macroom.

The ambush resulted in the deaths of three IRA Volunteers – Pat Deasy, Michael McCarthy and Jim Sullivan – and 17 Auxiliary cadets. There was a single Auxiliary survivor – Lt H.F. Forde.

The site of the ambush was a bend on the Macroom-Dunmanway road, which was bounded on either side by high, rocky ground.

The Kilmichael ambush became one of the most celebrated victories of the IRA during the war of independence – and it delivered a jolt to the British government and its estimation of the challenges it faced in Ireland in late 1920.

The British Prime Minister, Lloyd George was purported to have been horrified and it gave lie to his assertion earlier the same month that the British government had “murder by the throat” in Ireland. Moreover, the military-style character of the operation upended the notion that the challenge confronting the British government was simply one of restoring law and order. This was, as Lloyd George privately acknowledged, ‘a military operation’.

For republicans, after months of demoralising retreat, the ambush – following on from the attacks of Bloody Sunday morning – provided a morale-boosting shot in the arm.

In a recently published essay in the Atlas of the Irish Revolution historian W.H. Kautt states that the attack was ‘militarily rather minor’, yet perceptibly significant: ‘...it sent shock waves throughout Ireland and, indeed, the British government since the Auxiliaries were supposed to the corps d’elite’.

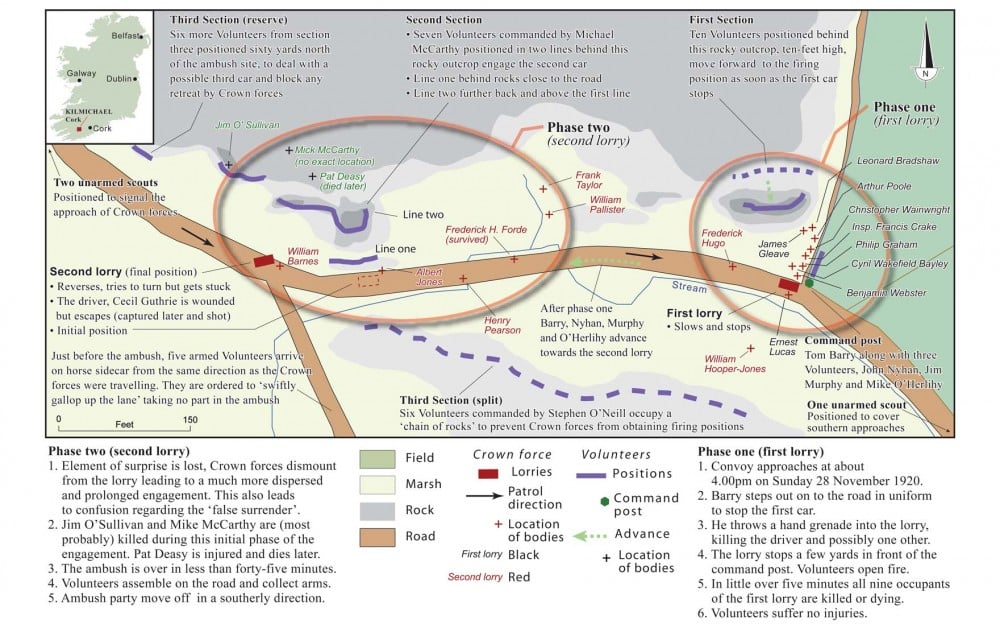

Map detailing the events at Kilmichael. Click image to enlarge. (Image: John Crowley, Donál Ó Drisceoil, Mike Murhy & Johnh Borgonovo eds., Atlas of the Irish Revolution (Cork University Press). Reproduced with permission)

Who were the Auxiliaries and why were they attacked at Kilmichael?

The Auxiliaries who travelled the Macroom-Dunmanway Road on 28

November were stationed at Macroom Castle. All were First World

War veterans and they had an average age of 27. A number of them

had been decorated: three had earned Military Crosses, while

another was the holder of a Distinguished Flying Cross. More

generally, the Auxiliaries were a special police force – the

Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary (ADRIC) –

that had been recruited during the summer of 1920 as an elite

counter-insurgency group to supplement the depleted ranks of the

RIC and complement the so-called Black and Tans, who had arrived

in Ireland in March that same year.

Where the Black and Tans were mostly drawn from rank and file ex-servicemen, the ADRIC were officer class – and they were paid accordingly. The £1 a day they received was more than twice the rate of an RIC constable.

Officer material or not, there was little difference in the conduct of the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries. Their reputation for ill-discipline and brutality was quickly established, well-earned and widely felt. It was evident in the practice of reprisal whereby civilian populations would be targeted in response to IRA attacks. An investigation by a British Labour Party Commission, conducted in the weeks after the Kilmichael ambush, observed that the class composition of the Auxiliaries was such as to make their conduct ‘depend more on the personality of local commanders than on instructions from head quarters...In the Auxiliary Division the men who matter are those possessed of ability and education, who are inflamed by political passion and who, so far as could be seen during the visit of the Commission, were being given a free hand in the south and west of Ireland. Wherever reprisals have been scientifically carried out so as to cause maximum economic and industrial loss to an Irish countryside or city, they have almost invariably been the work of detachments of cadets.’

Their controversial modus operandi notwithstanding, the effect of the Auxiliaries was indisputable. They may have hardened Irish outrage at the abuse of Imperial power, but they did appear to turn the course of the war of independence. According to the historian Peter Hart, their presence in Cork, as elsewhere, had ‘transformed the situation.... They raided constantly and aggressively. Where previously rural Volunteers might not have seen a policeman for weeks or months at a time, now there were safe havens’.

In his memoir, the Cork IRA Commander Tom Barry acknowledged this shift in dynamic.

‘The Auxiliary force had been allowed to bluster through the country for four or five months killing, beating, terrorising, and burning factories and homes. Strange as it may appear, not a single shot had been fired at them up to this by the IRA in any part of Ireland to halt their terror campaign. This fact had a very serious effect on the morale of the whole people as well as the IRA. Stories were current that the “Auxies” were superfighters and all but invincible. There could be no further delay in challenging them.’

Although two Auxiliaries had been killed at Mount Street on the morning of Bloody Sunday the week before, the ambush led by Tom Barry was the first to specifically target the division.

Who was Tom Barry?

Tom Barry was the column commander who led the ambush party at

Kilmichael.

His path to that leadership position was not exactly typical. Although west Cork born and raised, Barry had falsified his age in order to join the British army in 1915 and was wounded in the First World War during which he served in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Italy, and France.

The Ireland to which Barry returned had radically changed from that which he had departed. By the time of his return to Bandon in early 1919, Sinn Féin had swept to electoral success on its separatist republican platform and established an Irish parliament in the form of Dáil Éireann. Barry would later claim that his conversion to Irish nationalism came with learning of the 1916 Rising and his reading of Irish history, but he was a late entrant into the ranks of the IRA. Initially viewed with some suspicion owing his British military experience, Barry had been refused entry to the Bandon IRA before joining the west Cork Brigade in the summer of 1920.

While Barry brought an undoubted military nous to the local west Cork IRA, he was also acutely aware that the demands of guerrilla warfare were different to those of more traditional campaigns. Guerrilla warfare required a deep knowledge of local conditions and a capacity to act with speed when opportunities arose. This was a type of warfare that placed an emphasis on local leaders and local initiative rather than on a central command and control from the IRA’s General Headquarters in Dublin. It was a type of warfare, too, that relied on often ill-equipped and inexperienced volunteers. ‘The reality’, Barry wrote in his later years, ‘was a group of fellows, mostly in caps and not-too-expensive clothing, wondering how to tackle their job and where they would sleep that night or get their supper’.

The site of the Kilmichael Ambush (Image: Illustrated London News, 11 December 1920)

What happened at Kilmichael?

The Kilmichael ambush was the largest of the war of independence.

The site was chosen and operation planned by Tom Barry and it

occurred outside the territory covered by his west Cork brigade.

Those involved with the ambush were only told about the operation in the early hours of the morning of 28 November. The flying column of 36-riflemen gathered at O’Sullivan’s, Ahilina, each of them armed with a rifle and 35 rounds. A few also carried revolvers, while Tom Barry had two Mills bombs, which had been captured at a previous ambush at Toureen. The parish priest from Ballineen heard the men’s confessions and before leaving, asked Barry if the boys were “going to attack the Sassanach”. The priest wished the men well and gave them his blessing.

Having marched through the night-time rain and cold, the ambush party was in position by 9 am on the morning of 28 November. From then on until the late afternoon – supplied with tea and rations by occupants of a nearby farmhouse – they held their positions with, as Barry recalled, ‘nothing to do but wait, think and shiver in the biting cold.’

Just after 4pm, as dusk fell, a signal came from a scout that the Auxiliaries were coming along the Dunmanway-Macroom road. Barry and his men had been expecting them and were ready.

Barry had divided his flying column into three sections. The first was charged with attacking the first lorry and the second, positioned 120 yards further back the road, with attacking the second lorry. The third section was split, ‘occupying sniping positions along the other side of the road and also guarding both flanks.’

Tom Barry stepped out onto the road from his command post as two military lorries – with 18 Auxiliary cadets on board – advanced. As the first lorry slowed to a stop, Barry threw a grenade that exploded on landing in the uncovered driver’s seat – killing him instantly. As it did, IRA Volunteers on overlooking ground open fire.

Over the five minutes that followed, gunfire was exchanged and all nine occupants of the first lorry were left ‘dead or dying’.

The exchange with the Auxiliaries in the second lorry lasted longer. As soon the second lorry stopped and the Cadets began to dismount from the vehicle, they too came under heavy fire from two more Volunteer groups, who were positioned on either side of the road. The fighting that followed was intense and when it was ended – after about 45 minutes – all but two of the Auxiliary occupants of the second lorry would lie dead as would two members of the IRA ‘flying column’ – Jim O’Sullivan and Mick McCarthy. Another member of the ‘flying column’, Pat Deasy, died subsequently from his wounds at a farmhouse near Castletown Kinneigh. One of the surviving Auxiliaries made an escape from the scene, but was subsequently captured and killed.

In the telling of the Kilmichael story, it was the account provided by Tom Barry in his 1949 memoir, Guerilla days in Ireland, that made the biggest impression. It proved a best-seller and has frequently been reprinted.

In this memoir, Barry writes about a false surrender by the Auxiliaries. It occurred, he claimed, after the killing of the occupants of the first lorry, when he – Barry – and three others moved to assist the attack on the second lorry.

‘In single file, we ran crouched up the side of the road. We had gone about fifty yards when we heard the Auxiliaries shout “We surrender.” We kept running along the grass edge of the road as they repeated the surrender cry, and actually saw some Auxiliaries throw away their rifles. Firing stopped, but we continued, still unobserved, to jog towards them. Then we saw three of our comrades on No. 2 Section stand up, one crouched and two upright. Suddenly the Auxiliaries were firing again with revolvers. One of our three men spun around before he fell, and Pat Deasy staggered before he, too, went down.’

It was then that Barry gave the order: “Rapid Fire and do not stop until I tell you”. There would be further shouts of “We surrender” from Auxiliaries caught in the midst of gunfire from either side of the road. Barry was having none of it, however. He claimed in his memoir that he had ‘seen more than enough of their surrender tactics’ and so gave the order again to “Keep firing on them until the ceasfire.”

‘The small IRA group on the road was now standing up, firing as they advanced to within ten yards of the Auxiliaries. Then the “Cease Fire” was given and there was an uncanny silence as the sound o the last shot died away.’

WATCH: ‘The Fighting men of West Cork’ interviewed by RTÉ in 1969, among them Tom Barry

The Kilmichael Ambush | Episode 3 | The Irish Revolution | RTÉ One

What about the sole Auxiliary survivor?

An official report of the ambush was published and widely reported

in the press in early December and the following month, January

1921, testimony from the sole Auxiliary survivor was published in

the press, including the largest-selling Irish daily newspaper,

the Irish Independent.

Lt H.F. Forde had been travelling in the second lorry and recalled the moment the first lorry was attacked, hearing the gunfire and seeing “little puffs of smoke from here and there amongst the rocks.”

When the second lorry stopped, all its occupants, Forde said, scrambled out and took up positions on either side of the road, lying down to return fire. After about 10 minutes, Forde recalled, he was struck by a blow above the eye and began to feel sick. He continued: “I believe it was about ten minutes later than this that I suddenly heard a whistle blown loudly and a cry to cease fire. Then a large number of the attackers from both sides rushed into the road shouting in the foulest language. They wore the uniform of the British soldiers. These men proceeded to handle us all very roughly, not excepting even those who were by this time dead. After knocking us about they called on us all to stand up and hold our hands up.”

“There was no response for a time, but after about two minutes two of the party were able to stagger to their feet, and were immediately shot down at very close range by the Shinners.”

Why has there been controversy over the Kilmichael Ambush?

Few events in the Irish war of independence have been as

celebrated as the Kilmichael ambush.

The ballad, ‘The Boys of Kilmichael’, had already acquired popularity by the time Anglo-Irish war reached the point of truce in July 1921 – just over six months after the events at Kilmichael.

Its chorus proclaimed the ambush as a brave and honourable victory over the British foe:

So the here’s to the boys of Kilmichael.

Those brave men so gallant and true

Who fought ‘neath the green flag of Erin,

To conquer the red, white and blue

The same folkloric status that attached to the ambush equally attached to the man who masterminded.

However, while Tom Barry’s memoir remains the most popular account of what occurred at Kilmichael, it was not the only account that he provided. Nor was he the only participant to provide such an account. In the decades that followed, as historian Eve Morrison observed in 2012, ‘Accounts from Kilmichael participants were collected by individuals and institutions at different times with different purposes.’ Not all of these accounts were in agreement with those of Barry, as was the case with interviews conducted by Fr John Chisholm in 1969 that were used to inform Liam Deasy’s memoir, Towards Ireland Free, an account of his experiences with the West Cork brigade, which was published in 1973. Deasy’s account of the Kilmichael ambush – in which he had not personally participated but in which his younger brother, Pat, had died – infuriated Tom Barry. He objected to what he felt was his depiction as a ‘bloody-minded commander who exterminated the Auxiliaries without reason’ and responded with a rebuttal in pamphlet form, The reality of the Anglo-Irish war, 1920–21, in west Cork, which was published just after Deasy's death.

However, it was publication in 1998 of historian Peter Hart’s book, The IRA and its Enemies, that caused the greatest controversy and it informed almost all subsequent discussion and commentary around the Kilmichael ambush. The key point of the controversy was Hart’s contention that Barry had lied about the ‘false surrender’ of the Auxiliaries and that the story had been invented in order to justify their killing.

The book caused a major stir and Hart’s analysis did not go unchallenged. Indeed, in the years after its publication, debates raged in the press and elsewhere about sources and historical interpretation.

Addressing the various and often conflicting accounts of participants, Charles Townsend, writing in 2013, observed that there ‘can be inconsistencies even among genuine testimonies, and these events are unlikely ever to be precisely reconstructed. The most systematic attempt so far to weigh all the evidence and interpretations of the fighting (Seamus Fox, 2005) runs to over thirty pages, and finds no clear way out of the tangle.’

Diarmaid Ferriter, too, warned against reaching definitive verdicts. In his 2015 book, A Nation not a Rabble, Ferriter observed: ‘None of the arguments about the ambush have been proved conclusively and the contradictory evidence over what happened does not merit emphatic conclusions.’

Next year, in April 2021, a new book by from historian Eve Morrison will re-examine the events of 28 November 1920, the various participant accounts given and the controversies that have followed in its wake. Kilmichael: The Life and Afterlife of an Ambush will be published by Irish Academic Press.

What happened in the immediate aftermath of the ambush at Kilmichael?

Speaking in the House of Commons on 30 November – his first

comment on the incident in the chamber – the Chief Secretary

for Ireland, Sir Hamar Greenwood, described the ambushed

Auxiliaries in Cork as “gallant officers who were victims of

the assassination.”

He said little more about it, but his characterisation of the ambush echoed the commentary in the conservative and unionist newspapers. The Irish Times editorialised that what had occurred had been ‘another hideous outrage’ and ‘another of those blots on the name of Ireland which the repentance and sorrow of many generations will not expunge.’

In terms of policy, Kilmichael led to a stiffening of an already hard-line approach to counter-insurgency. Martial law was introduced across much of the Munster region.

In addition, the British policy of reprisal – unofficial and official – now took on an ever more severe character. In the immediate aftermath of events at Kilmichael, Crown forces went on a house burning spree in the locality that left few properties undamaged and many destroyed completely.

More carnage would follow soon after. On the night 11-12 December large swathes of Cork City’s centre would be razed to the ground, burned by Auxiliaries as a reprisal for an earlier IRA ambush at Dillon’s Cross. ‘Last night in Cork was such a night of destruction and terror as we have not yet had,’ Sinn Féin TD, Liam de Róiste, observed the following morning. ‘An orgy of destruction and ruin: the calm sky frosty red – red as blood with the burning city, and the pale cold stars looking down on the scene of desolation and frightfulness. The finest premises in the city are destroyed, the City Hall and the Free Library.’

And Tom Barry, I presume he got a Military Service Pension?

Yes. In January 1940, the Military Service board adjudicated on a

claim for pension on behalf of Tom Barry. After weighing up the

testimony and the evidence, the board decided against granting

Barry the highest level of pension award. Instead of a Rank A

pension, he received a Rank B pension. Barry was incensed.

Appealing the judgment he described the original award as

‘humiliating to a degree...I am feeling ashamed and

ridiculous at the award and that I am entitled at least to have

this humiliation removed from me.’

Barry was, nevertheless, among the minority of successful pension applicants. Of the 82,000 people who applied under the Pensions legislation of 1924 and 1934, only 15,700 – Barry among them – were successful.

Still, his complaint had the desired effect. On appeal, his award was upgraded to a Rank A pension.

VIEW: Thomas Barry Military Service Pension file here

Has the Kilmichael ambush been commemorated?

Yes. Extensively. Perhaps the most significant act of the

commemoration was the erection of a large monument at the ambush

site in 1966, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the 1916

Rising. Prior to that, only a simple iron cross had marked the

spot.

Tom Barry and several others who had participated in the ambush were still alive and formed a guard of honour at the unveiling ceremony of the monument, which was performed by the local parish priest. The veterans walked behind a banner bearing the title of the popular ballad written in honour of their deeds, ‘The Boys of Kilmichael’.

The carved limestone monument remains in place today and bears the inscription: ‘They shall be spoken of among their people. The generations shall remember them and call them blessed.’

WATCH: The RTÉ television news report about the monument’s unveiling, 10 July 1966