Éamon de Valera and the 1920 American presidential campaign

By Prof Bernadette Whelan

Éamon de Valera, president of Dáil Eireann, was in the US from June 1919 to December 1920 to secure financial support for and diplomatic recognition of the new Irish republic. By March 1920, the Irish American republican movement had split over control of funds, fund-raising, strategy and personality differences between the most powerful figure in Irish America, Judge Daniel Cohalan who was a senior Clan na Gael member and leader of the Friends of Irish Freedom, the major fund raising body for Irish republicans in the United States, and de Valera.

Also in March 1920 the Treaty of Versailles and Covenant of the League of Nations were defeated again in the US senate. President Woodrow Wilson’s post-war peace plans were shattered and resulted in him believing that Irish American leaders particularly Cohalan who had allied with the Republican party, were ‘evil men’. These March 1920 events provide the context to de Valera’s engagement with the American presidential election campaign.

The four-year occurrence of an American election was, and remains, an opportunity for interest groups to lobby parties and candidates for promises of action in return for votes. But how powerful was the ‘Irish vote’ in American elections? Irish Americans had helped bring Wilson to office in 1912 and returned him in 1916 even though he had not protested to the British government about its treatment of Irish republican prisoners after the rising. In 1920 British officials believed in the existence of an ‘Irish vote’ which American politicians ‘even against their convictions … bid for’ at election time. In spring 1920, given the publicity arising from the escalating Anglo-Irish war of independence, it was not surprising that the British embassy expected the Irish question to figure prominently at the respective party conventions, in the platforms and during the campaign. But British diplomats often under-estimated the influence of domestic factors with the US voter irrespective of ethnicity.

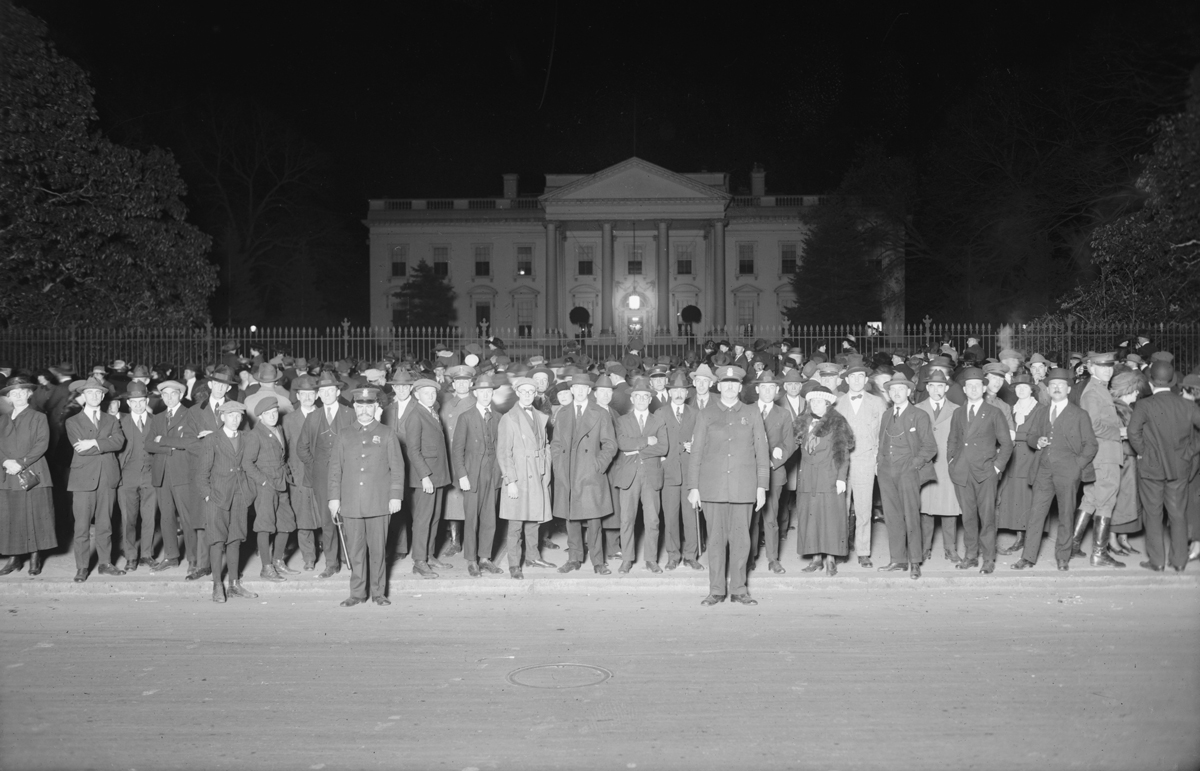

Both Cohalan and de Valera agreed on 22 May that it was important to have a coherent approach to the Republican party convention to be held in Chicago on 8-13 June. They wanted to have inserted into the party platform a promise to recognise the Irish republic. But Cohalan opposed de Valera’s attendance at the convention as did some of de Valera’s advisers particularly Frank P. Walsh who cautioned against a foreigner being seen to interfere in US domestic affairs. De Valera decided to attend and on 4 June arrived in Chicago where a large crowd awaited him.

In any US presidential year, the content of the platform to be presented as policy to the public and the choice of candidate dominates the respective party conventions. Cohalan’s proposal to a resolutions sub-committee called for a statement in favour of self-determination for Ireland which he believed had secured advance support from some Republican delegates and leaders particularly Senators William Borah and Hiram Johnson respectively. De Valera’s more detailed proposal sought ‘full, normal and official recognition.’ Despite secret efforts to negotiate a compromise, the sub-committee rejected de Valera’s resolution and approved Cohalan’s version. After de Valera publicly criticised Cohalan’s plank, the whole committee of 57 members voted not to include any Irish resolution in the final platform. The Cohalan–de Valera divide spared a future Republican administration from any commitment to act on Ireland’s behalf. As Auckland Geddes, the recently-appointed British ambassador in Washington, noted, ‘the incident illustrates … the immense influence Irishmen can have on American politicians if they proceed wisely; and how ready American politicians are to withdraw themselves from that influence if they can find some colourable pretext for doing so.’ The Irish tactics had backfired and left both factions with nothing from the convention. Evidently the alliance between Irish America and the Republican party during the League of Nations fight was one of expediency.

After the platform was approved, the struggle for the presidential nomination continued, the main contenders were General Leonard Wood, Frank O. Lowden, Calvin Coolidge, Senator Warren G. Harding and Senator Hiram Johnson. None of the candidates had openly identified his candidature with Ireland’s cause. Cohalan favoured Johnson because he hoped that William Borah, his ally, might be appointed secretary of State. De Valera did not express a public opinion about any candidate. Harding won and chose Coolidge as his vice-president.

De Valera, but not Cohalan, left for the Democratic party convention in San Francisco which began on 28 June, to start the campaign again. He was greeted by crowds emphasising the extent of public recognition of him as the leader of the Irish republic. According to Harry Boland, his ally and the Dáil Éireann representative to the US, de Valera had ‘great hopes’ of getting the Democratic party to support recognition because of the prominence of Irish Americans as party members, representatives, organisers and donors. But many party leaders were also disgruntled that since 1919 Cohalan had tied the Irish cause to their opponents.

President Woodrow Wilson’s private secretary Joseph Tumulty, along with Attorney General Mitchell Palmer and Senators Gerry, Glass and Thomas J. Walsh, appealed to him to frame a plank endorsing Irish aspirations for national self-determination. The group felt that it would make the Democratic party more attractive to the Irish voter in November. Wilson ignored the request. But the powerful bosses faction - Charles Murphy of Tammany Hall, Thomas Taggart of Indiana, George Brennan of Illinois - were ‘perfectly frank’ in their demand that ‘as the icing on the shamrock’, they wanted a platform plank favouring Irish independence. Moreover, Senator David I. Walsh and Senator Bourke Cockran, both supporters of the Irish cause, were members of the resolutions committee which heard de Valera’s and Frank P. Walsh’s arguments. The Irish proposal was defeated in the committee by 31 votes to 17. A further milder plank was defeated on the convention floor by a vote of 665½ to 402½. The delegates finished the session by merely expressing ‘sympathy’ for Irish aspirations which were vague, particularly when compared to expressions of admiration for other recently established representative governments in Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and Poland among other places.

The candidate’s nomination process was equally laborious. By 2 July, the door was finally closed on a third term for Wilson and three days later James Cox was victorious. He chose Franklin Delano Roosevelt (under secretary of the Navy) as vice-presidential candidate whom de Valera had met in 1919.

For traditional and practical reasons, sympathy for the Irish problem remained strong within the Democratic party, but not so strong as to tie the party or presidential candidate to any action on the matter. De Valera believed that the Democratic party had underestimated ‘the great volume of public sentiment in this country behind the demand for justice in Ireland.’ But he failed to recognise the gap between sentiment and pragmatism. British Ambassador Geddes was relieved; ‘it has been possible to avoid an Irish plank that matters in either platform.’

De Valera was tired after his failed efforts to persuade the major party conventions to declare in favour of recognition. However, he decided to seek the endorsement of another political grouping, the Farmer-Labor party, at their convention in Chicago. Between 10 and 13 July, de Valera was well-received by municipal labour leaders such as John Fitzpatrick, president of the Chicago Federation of Labor, one of the most powerful labour bodies. Labour leaders were convinced that ethnic nationalism could be directed towards advancing labour politics and the labour movement could promote nationalist causes. The party supported the recognition of legitimate governments in Ireland, Mexico and Russia. It was a small victory. De Valera and Boland hoped that it would force the larger parties to take notice but did not urge Irish Americans to rally behind the party. De Valera did not approach the Socialists or Prohibitionists.

In mid-summer 1920, at a time when British actions in Ireland were producing powerful material for Irish republican propaganda and lobbying campaigns in the US, the political clout of the Irish movement had been weakened by the Cohalan/de Valera split. After Chicago, de Valera refrained from directly commenting on the presidential election because as Boland said ‘if we get deep into American politics we will be skinned’. Instead de Valera focused on, firstly, gaining control of the Friends of Irish Freedom and eventually establishing a rival organisation, the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic; secondly, fund-raising; thirdly, managing the visits of his wife, Sineád, which she later described as a ‘huge blunder’, and that of Daniel Mannix, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Melbourne, who was a rabid Irish republican; and finally, he worked to ‘secure [American] public opinion’ which he hoped would influence the new administration to adopt recognition as ‘this country’s official policy’ and to re-engage in international diplomacy to Ireland’s benefit.

Harding, as an experienced politician and newspaperman, launched his campaign on 22 July in Marion, Ohio, and ran an effective campaign preaching ‘American first’ and promoting a ‘return to normalcy’ after the Wilson years. On 7 August Cox embarked on an extensive nation-wide tour but the Democrats had less money than the Republicans and party headquarters were slow to organise.

Soon the candidates had to respond to the growing public disgust at Britain’s draconian security policy in Ireland and calls for an American relief operation in Ireland and the establishment of an American commission to investigate events in Ireland. News about murders of citizens, the burning of towns and daily outrages also increased the intensity of de Valera’s speeches and the fund raising but he was not arrested.

When questioned about independence for Ireland on 23 September, Harding showed himself to be representative of the traditional Republican party view that the Irish problem was a domestic British one in which the US had no role, even though he expressed sympathy for the cause of Irish freedom. But the Democratic party countered that ‘on every roll call Senator Harding … voted against the principle of self-determination for Ireland.’ Despite this, John Devoy in the Gaelic American advised readers to vote for Harding ‘as the surest method of defeating Woodrow Wilson’. Meanwhile Cox declared that the Irish people deserved to be independent, if they so wished. But the Gaelic American, warned its readers that Cox ‘was a mere puppet of … Wilson’. By October, Cox was desperate to woo back the disillusioned Irish American voters and promised action on the Irish problem. British Prime Minister Lloyd George warned US Ambassador Davis that ‘“Ireland [is] our business”’.

News of the death on hunger strike of Terence MacSwiney, the Sinn Féin lord mayor of Cork city, on 25 October, influenced de Valera to make one final intervention in American politics. On 27 October a formal request for the recognition of the Irish republic was presented to Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby. It was a futile effort as Wilson had no intention of reversing his non-interference policy on Ireland.

Harding and Coolidge won a popular victory with 16 million votes as against 9 million for Cox and Roosevelt, while the electoral college vote was 404 to 127 respectively. Geddes commented that ‘for the first time on record, an electoral campaign has been conducted in the United States without the political ‘crimes’ of England being dragged into the fray.’ The combination of the promise of lower taxes, less government intervention, high tariffs, frugal administration, Democratic party weaknesses on many fronts and Harding’s ability to draw a pleasing picture of the ‘normalcy’ to which he would return the country was as effective with many Irish American voters as it was with any other type of voter.

After 100 years of retrospection, examining de Valera and the 1920 American presidential election reminds us firstly, that Irish America is not a homogenous community to be relied on to vote as a bloc on Ireland’s behalf, and secondly, that de Valera and subsequent Irish nationalist leaders could be flexible in their approach to the American polity in order to achieve their aims. Essentially Irish influence in US party politics is limited yet, Irish leaders still believe in the myth of a ‘special relationship’.

Professor emeritus Bernadette Whelan MRIA, is the author of many books and articles on America and Ireland including United States Foreign Policy and Ireland, 1913-29: From empire to independence (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2006). De Valera and Roosevelt. Irish and American diplomacy in times of crisis, 1932-1939 will be published by Cambridge University Press in November 2020.