Dublin Castle, 1920-22: the last days of an old regime

John Gibney and Kate O’Malley

The importance of Dublin Castle to Irish history is straightforward enough; it was the home of the British administrations that ruled Ireland up to 1922. In 1204 King John ordered the construction of what became Dublin Castle, on elevated ground alongside the feature that gave Dublin its name: the ‘Dubh Linn’, or black pool, which was formed by the meeting of the rivers Liffey and Poddle. Dublin Castle evolved over time and by the early twentieth century would have been virtually unrecognisable as a medieval citadel, being tucked away from view within the bustling commercial and retail district that had built up on what was once the edge of the old city.

Visitors to the castle were often underwhelmed by its appearance. But Dublin Castle was where the levers of power were. All political, security and financial policies evolved there. While the organs of the British administration were scattered across a variety of locations in Dublin, the principal offices were located within the walls of the castle. The nationalist journalist R. Barry O’Brien succinctly captured this point in 1909: ‘politically, the Castle is the Executive, and the Executive consists of the Lord Lieutenant, the Chief Secretary and the Under-Secretary’ (the latter was the deputy to the Chief Secretary, who was the minister in charge of Irish affairs). Next in the castle hierarchy came the chief legal officers and the heads of the departments. Security policy too was shaped in the castle: it housed the commissioner of the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) and the Inspector-General of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), and the prison board, and alongside these were organs of central administration such as the treasury and financial offices, along with myriad other official bodies. The significance accorded to Dublin Castle arose, in part, because decisions were made there.

By the end of 1919, the British coalition government of David Lloyd George had recognised that a withdrawal from Ireland’s domestic affairs was a political necessity for a settlement of the ‘Irish question.’ A necessary prelude was the reform and restructuring of the government based within Dublin Castle. In May 1920 Sir Warren Fisher, the secretary of the British treasury, subjected the castle regime to a scathing critique. There was some acknowledgement that the castle had often simply picked up the pieces left by decisions made in isolation in London. But Fisher bemoaned the hard-line political stance of the Dublin Castle administration and its alignment with the ‘ascendancy’, and effectively recommended a purge of the key positions in a government which he characterised as ‘almost woodenly stupid and quite devoid of imagination.’ A raft of new appointments to key positions would follow, along with a distinct change in policy and approach. But this was the prelude to a settlement, and the castle’s reputation was almost certainly beyond redemption in the eyes of nationalist Ireland. George Chester Duggan, who served in a senior role in the chief secretary’s office, put it more bluntly: government policy in Ireland was ‘always damned under the title “Dublin Castle”.’

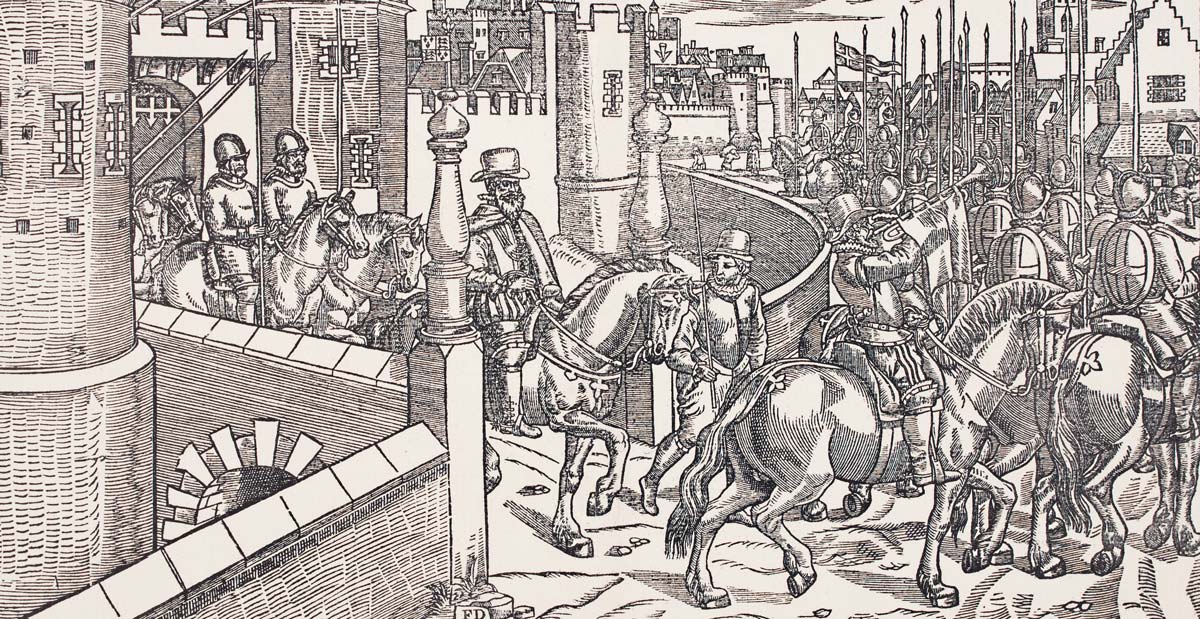

An early depiction of Dublin Castle can be seen in this woodcut from John Derricke’s The image of Irelande (London, 1580), written in praise of the Tudor viceroy Sir Henry Sidney. The image depicts Sidney at the head of an English army departing from Dublin Castle; the spire of Christ Church can be seen on the top right-hand corner, with severed heads on spikes visible in the top left (Image: NLI, Prints and Drawings, PD 4061 TX 6; courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

While the British government recognised the need for a political settlement of some kind in Ireland, they had also committed themselves to crushing the independence movement. The Irish War of Independence intensified in scale and scope throughout 1920 and Dublin Castle became increasingly fortified as the conflict unfolded. Three companies of the newly recruited Auxiliary Cadets (a paramilitary adjunct to the RIC) were based there. One of them, F Company, actively participated in raids around the city. In August 1920 many officials and civil servants, including some seconded from England who had previously been ensconced in the Marine Hotel in Kingstown (renamed Dún Laoghaire the same month), relocated themselves to the safer confines of Dublin Castle. The Mayo-born revolutionary Ernie O’Malley noted how, by autumn 1920 the Castle ‘was again a fortress which higher officials seldom left openly.’ For security reasons even the recently appointed Under-Secretary, Sir John Anderson, and his colleagues in the Irish administration were advised to live within the cramped confines of Dublin Castle, where their offices were situated. Anderson took up riding for exercise, unperturbed in the face of the threat of assassination by the IRA, but others were soon targeted.

The most notorious events of the War of Independence in Dublin came on ‘Bloody Sunday’, 21 November 1920 when the IRA killed numerous British officers (along with some civilians) at their lodgings around Dublin. This was a watershed in the conflict; its immediate consequence was a British attack on a crowd attending a match at Croke Park, in which fourteen spectators and players were killed. Concerns over the implications of the IRA attacks prompted even more officials and security personnel to relocate to the castle. A number of adjacent buildings, which had been requisitioned as buffers to protect the Castle from attacks, were pressed into service as accommodation (In January 1921 number 3 and 4 Palace Street, near the entrance to the lower yard of the castle, were commandeered as being ‘dangerous houses’). Overcrowding led to a ban on wives moving in, though some were enrolled as typists to get around this stricture and were apparently accommodated on Palace Street. But remarkably some families lived inside Dublin Castle, where the children led, according to Duggan’s recollections of the hustle and bustle within, ‘an Arcadian existence, without lessons, without governesses.’ If this was true for children, it was certainly not the case for the adults. The ongoing confinement of people within the complex ensured that tennis courts were laid out in the walled garden behind the state apartments which permitted some degree of exercise and entertainment. Eamon Broy of the DMP, who provided information to the IRA during the War of Independence, recalled in his statement to the Bureau of Military History how DMP commissioner Edgeworth Johnstone was accustomed to walking in and out to the castle from his home in Booterstown until ‘it dawned on him in early 1920 that this was no longer a healthy habit.’ He moved into the castle, where he and other senior officers now tried their best to exercise, in dispirited fashion, ‘inside the comparative safety of the Lower Castle yard.’

The exterior of the castle, insofar as it could be seen, told its own story about the conflict. The lower gate and its adjacent buildings were draped with barbed wire and mesh to prevent bomb attacks. There was even barbed wire placed inside the culvert for the River Poddle, regularly checked by Royal Engineers. Sentries and machine guns posts were placed on some of the more exposed rooftops such as the record tower, where the union flag usually flew. Canvas screens were erected inside the complex to prevent the movements of people and vehicles from being seen from nearby rooftops. The gate to the upper yard, beside City Hall on Cork Hill was closed, while the lower gate on Palace Street was guarded by military police and members of the DMP who could draw upon the services of the Auxiliaries as required. The lower yard was used as parking for military vehicles, and Patrick Moylett, who was acting as a go-between as the British moved towards negotiations, recalled Auxiliaries outside the Chapel Royal in May 1921 ‘firing revolver shots at small barrels filled with clay, the class of barrels that came from Spain with grapes.’ David Neligan (another member of the DMP who assisted the IRA) gave the Bureau of Military History a vivid account of the castle ‘virtually in a state of siege’:

All night long the Square gleamed with headlights as raiding parties came and went. Officers and civilians dashed in and out in covered oars. About 100 Auxiliaries were quartered there - the notorious ‘F’ Company. They were an extraordinary collection. I saw men in Airmen's uniforms, highlanders complete in kilt, Naval officers, Cowboys and types from every quarter of the globe. A sprinkling of the crowd wore the blue tunics of the R.I.C. with the letters ‘T.C.’ (temporary cadets). All wore glengarry caps. Some wore old British Army uniforms. Auxiliaries were paid £7 (seven pounds) a week, most of which went to the Canteen, which did a roaring trade, night and day. Once, when cash ran out, a squad raided the City Hall in broad daylight and stole several thousand pounds. Night after night a dark tall fellow wearing a Colonel's epaulettes and a glengarry cap was frog-marched to a lorry by his men. I did not know his name. Some of them, including the S.S. men, adopted a different name for every day of the week. He was so drunk that he could not proceed under his own steam but at the same time insisted on going out to look for the ‘Damn Shinners.’ He was left in the front seat of an open Crossley tender, a pair of which always travelled together.

Members of F Company of the Auxiliary Division of the RIC, photographed in uniform with the Chapel Royal in the background, c. 1920. Recruitment for this paramilitary unit began in July 1920, and these new forces acquired an unevniable reputation for brutality and indiscipline after they were deployed as the British administration in Ireland stepped up its campaign against the IRA. The photograph is from the papers of Piaras Béaslaí, who was a publicity offier for the Dáil government and the editor of the IRA newspaper An tÓglach. It appears to have been annotated, possibly to identify those pictured (Image: NLI, Piaras Béaslaí collection, BEA 12; courtesy of the National Library of Ireland)

The IRA carried out many attacks in central Dublin throughout the conflict, but Neligan was quite scathing of the fact that ‘from the beginning to the end one serious attack was not launched on the Castle Auxiliaries.’ Likewise, according to Eamon Broy, ‘[Michael] Collins had plans all the time for burning or blowing up portions of Dublin Castle…However, nothing ever happened afterwards in this line.’

What the IRA could and did do was obtain useful information from within the castle from individuals working there, from sympathetic policemen like Broy and Neligan, and staff members like the typist Lily Mernin, who, amongst other things, supplied the details of many of those killed on Bloody Sunday. Such information generally related to security matters; it proved virtually impossible for the IRA to obtain intelligence from within the castle administration itself.

During this period the castle was used for the temporary detention of suspects before their transfer to prison; City Hall, located beside the castle, had been seized by the British army in December 1920 and was used to host courts martial. Detention in the castle could often involve brutal treatment at the hands of the army and police, as the young IRA volunteer C. S. (Todd) Andrews observed. Having been picked up near O’Connell Street Andrews, who gave his captors a false name, was taken to what appeared to be the guard room in Dublin Castle, adjacent to Exchange Court. He was regularly marched through the castle to exercise outside Ship Street Barracks, in what he felt were effectively ‘identification parades.’ After a few days Andrews was eventually brought for questioning in the State Apartments, where he noted the incongruous presence of a vase of daffodils (‘except for the Auxiliary in the background and the daffodils, the scene might well have been an interview in the public service’). Andrews was treated reasonably well, partly as he successfully convinced his interrogators that he was in Sinn Féin but not the IRA. But after being returned to detention in the castle he briefly encountered a prisoner who had been badly beaten in custody following an IRA ambush on Brunswick (Pearse) Street. It disabused him of the notion that British regular forces were less likely to mistreat prisoners than their paramilitary counterparts. Andrews was soon transferred to Arbour Hill: ‘I was delighted to get out of the Castle.’

Others were less fortunate. Ernie O’Malley recalled friendly encounters with Auxiliaries while imprisoned in Dublin Castle at Christmas 1920, but also left a vivid account of his torture there. His recollection of his detention was, in later life, intertwined with a sense of the Castle’s history, describing it at this time as ‘the symbol of all that was hateful in the British domination of Ireland’ as well as ‘the great symbol of misgovernment in the people’s minds.’ His own treatment, in his reading of his life, seemed to place him in a long line of those who had suffered at the hands of the regimes based in the castle. But O’Malley lived to tell his tale; others did not. On the night of Bloody Sunday, 21 November 1920, Peadar Clancy and Dick McKee of the Dublin Brigade, along with a civilian, Conor Clune, were apparently tortured in the castle before being killed, having been picked up the night before; the official story was that they were killed while trying to escape. Eoin MacNeill – later a member of the Provisional Government that would assume power in the same castle in January 1922 – was subsequently detained in the ‘murder room’ of the castle, and was shown a ‘mark on the side of the wall’ by one of his captors, who said ‘Do you know what that is? That’s the brains of some of your lot.’ Such incidents magnified the already sinister reputation the castle had in the eyes of republicans and nationalists.

Dublin Castle during the War of Independence was an intense, claustrophobic environment. Some limited social and musical events did take place there during the war, mainly for the benefit of its overwhelmingly British residents. Any potential perception of insensitivity was outweighed by the need to let off some steam in the course of a lengthy confinement, though they also ‘enabled the remnants of Dublin society to invade the Castle precincts in the afternoon and while away the official hours by jazz or foxtrot.’ In January 1921 there was much consternation when F. Company of the Auxiliaries tried to take advantage of the absence of some senior officers by staging a New Year’s Eve ball in St Patricks Hall and were found selling tickets for the event. The exasperated civil servant Mark Sturgis noted in his diary that most of those who worked and now lived in the castle had to adhere to rigorous security checks, ‘yet these beauties can almost without by your leave or with your leave import a pack of women of whom nobody with the possible exception of themselves knows anything at all. Interesting to see when I get back to-morrow whether the Shinns have got in disguised as buxom wenches or whether failing this the whole place has been fired up by the festive ex-officers themselves.’

‘In the castle’: cartoon produced for the Freeman’s Journal (10 January 1922) by its cartoonist ‘Shemus’ (Ernest Forbes). It depicts General Neville Macready reading a copy of the Freeman’s Journal while an armed Black and Tan peers over his shoulder. The caption ran: ‘The Black and Tan: “Any orders to-day, sir?”. General Macready: “Pack your kit and stand by to embark.”’

This was not an isolated incident either. According to Lily Mernin, ‘the Auxiliaries also organised smoking concerts and whist drives in the Lower Castle Yard’, and some of them saw their female visitors to the tram afterwards, only to be shadowed by IRA members seeking to identify them. Security in and around the castle intensified as the conflict dragged on, but the IRA tried to exploit any vulnerabilities. George Duggan, for example, left a mordant observation (in his own account of ‘the last days of Dublin Castle’) about the photographic identification that was introduced to get in and out of the castle. This was ‘admirably suited to London offices in wartime’ but in Ireland such documents were ‘a menace to those labelled in this way’; he blamed them for the death of at least one officer, and photographs were ultimately abandoned, to be replaced by the memory and discretion of the castle guard. The threatening atmosphere in the streets around the castle, and the city at large, weighed upon some of those who worked there. Duggan recalled that ‘as one left the Castle one had a feeling of watchfulness. As I walked up Dame Street I have at times looked back with that - sub-conscious sense of being followed - and by whom? The life of a Civil Servant in London seemed hum-drum when compared with this brooding sense of fatality, but I don't suppose many English Civil Servants would have wished to exchange places.’

The air of menace felt in Dublin on the part of officialdom dissipated with the truce of July 1921. Afterwards, officials and civil servants began to venture out once more. The castle remained under guard, though Duggan noted that the canvas screens in the lower castle yard ‘were allowed to fall into disrepair, and hung for many months in unsightly remnants.’ In the meantime, ‘the Auxiliaries beat their swords into ploughshares, and Lancia lorries, instead of bearing them forth from the Castle gates clad in the panoply of war, sallied out on the more peaceful errands of bearing towel-girt warriors to the pellucid depths of the forty-foot at Sandy-Cove.’ In September Todd Andrews was surprised to find the life of the city proceeding with total indifference to ‘the great issues of peace or war.’ Theatres and cinemas were busy, race meetings (‘racing people were exceptionally low in my scale of values’) were being held across the country, and Andrews ‘began to wonder did it really matter to the man in the street whether the British stayed or got out.’

Yet this was the issue that lurked in the background. On 7 December 1921, the day after the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in London, the Freeman’s Journal despatched a correspondent to the castle, where they were told by an official that ‘there is nothing new here.’

‘Not yet?’

‘Oh, not yet, of course.’

The paper reported ‘an air of vacancy and spiritlessness’ in the castle. Just inside the gate, ‘Two Black and Tans were sparring and chaffing each other in Cockney accents. Beyond them was the blank emptiness of the Lower yard, relieved only by an infantry officer who, with cane under arm and hands behind back, strolled rather dejectedly in the direction of Headquarters. The bustle of the Irish war days had departed.’ It was ‘the interregnum...for the moment the Castle is awaiting orders.’ The impression of an era being brought to its end was reinforced by other changes, as the security around the castle was gradually dismantled. On 10 January 1922 Mark Sturgis noted in his diary that ‘The Castle makes a good propaganda appearance with its gate standing open for the first time in at least two years and soldiers busy removing barbed wire.’

Less than a week later a newly appointed ‘Provisional Government’, comprised of men who throughout the War of Independence had been the enemies of the British regime, would arrive in Dublin Castle to be officially installed as the body that was to oversee the transition from British to Irish rule. It prompted an oft-quoted passage in the Irish Times of 17 January 1922, one that neatly sums up the understated reality of that event: ‘After the fluctuating history of seven centuries Dublin Castle is no longer the fortress of British power in Ireland. Having withstood the attacks of successive generations of rebels, it was quietly handed over yesterday to eight gentlemen in three taxi-cabs.’

John Gibney and Kate O’Malley are historians and assistant editors with the Documents on Irish Foreign Policy series, a partnership project of the Royal Irish Academy, the Department of Foreign Affairs and the National Archives. This is an edited extract from their new book The Handover: Dublin Castle and the British withdrawal from Ireland, 1922, published by the Royal Irish Academy.