Democratic revolution in Ireland & the interwar world

By Maurice Walsh

In the summer of 1923, an English young writer called Graham Greene visited Dublin on his first reporting trip abroad and was impressed by the city’s tolerance of poverty and neglect. The houses were ‘dilapidated’, the roads ‘unswept’. Grafton Street and Sackville Street ‘would disgrace an English country town’ and beggars were ‘as numerous as in a continental port’. But it was his description of the forces of law and order that would have appalled the new rulers of the Irish Free State, by then contemplating victory over the anti-treaty IRA. The Garda Síochána, Greene conceded, looked ‘smart and well disciplined’ but, being unarmed, they were ‘useless save for ordinary police routine’. The national army consisted of either old men or boys with so little discipline that only one in 50 would salute an officer. ‘One picture remains firmly in my mind’, Greene wrote, ‘that of a small boy of about fifteen, in the green uniform of the Free State, fast asleep on a bench in St Stephen’s Green, his head resting on the shoulder of a still younger girl.’

The image conveyed to outsiders by such a scene of laxity was what worried the new Minister from Home Affairs, Kevin O’Higgins. He classed the civil war as ‘anarchy with arms’ and was worried about the potential damage to Ireland’s international reputation. The Irish, O’Higgins feared – in an insight into the power of racial thinking at the time – were in danger of being classed as ‘as a people unable to govern themselves’ like Mexicans or blacks. Indeed, there were already hints that the chaos of the civil war could lead to Ireland being regarded as a failed state, spiralling into such a calamitous state of collapse that Britain might even be able to justify re-occupation to restore order. In October 1922, a British journal remarked that ‘Ireland’s failure strengthens the cause of those who believe in strong imperial government rather than democracy’. This verdict represented a humiliating comedown for a country that had so successfully courted international attention and a revolutionary movement that had been so good at making Ireland a world issue, putting British policy in the wrong. In a memorandum written in the same year, George Gavan Duffy – the Minister for Foreign Affairs in the new Free State government – argued that Ireland could be a force to be reckoned within the League of Nations because it was regarded as standing for ‘democratic principles, against Imperialism and upon the side of liberty throughout the world’.

The establishment of Dáil Éireann was central to Ireland’s claim to be a democratic state unworthy of colonial rule. The dignified ceremony with which the Dáil had assembled in January 1919 had, as intended, drawn attention from all over the world. In the ‘Message to the Free Nations of the World’, proclaimed on the day, it was pointed out that Ireland was not a contrived state, brought to life by some hasty re-drawing of lines on a map but one of the most ancient nations in Europe ‘who had asserted nationhood by force of arms in every generation’. The deputies called on every free nation to support the vindication of the Irish Republic at the peace conference, deftly placing Ireland in the ranks of the sovereign nations.

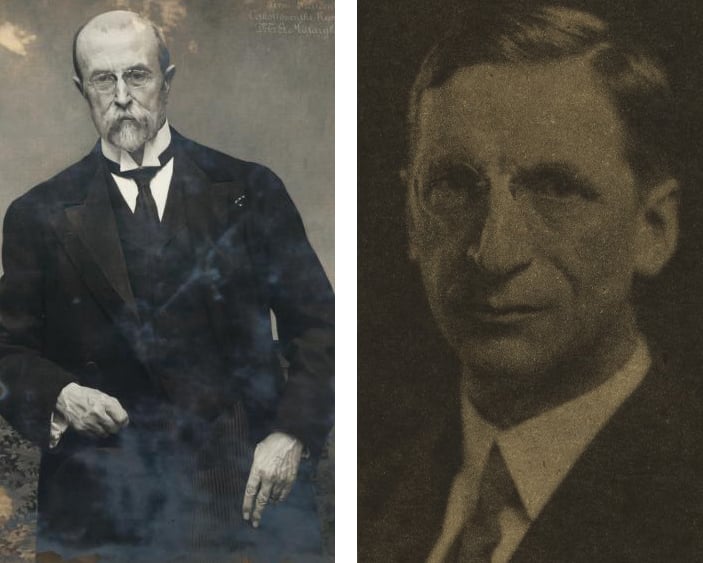

Pictured side by side are Tomas Masaryk and Eamon de Valera. Like de Valera would do, Masaryk styled himself as the father of the nation and was presented as an apostle of democracy, a great European. Unlike the Irish revolutionaries, however, the Czechs had supported the Allies in war from the beginning and were now looked on favourably by the victors in the post-war reconstruction of Europe (Images: New York Public Library)

Some of the many observers who had come to watch the opening of the new parliament had scoffed. The Times suggested that the Dáil would be the beginning of the end for Sinn Féin; the Daily Mail reported that the gathering in the Mansion House could easily be mistaken for ‘a meeting to found a new musical society’. Even the Manchester Guardian, broadly sympathetic to Irish nationalism, reported that the Dáil was in danger of being viewed as ‘a mere pantomime’. But the stage managers, who had carefully choreographed the opening session to make it look as natural as possible, believed that the image of a genuinely republican parliament would endure; they aimed for Westminster-style decorum without the medieval trappings. Frank Gallagher was satisfied that the proceedings were conducted with dignity and that the audience had matched the nobility of the occasion. There may have been no mace or standard-bearers but ‘it was clear that it was the representatives of Democracy who had met’ and that they derived their authority from the people.

The important person to impress was Woodrow Wilson. Nearly 30 years earlier when he was a mere university professor, the American president had written that the advance of democratic thinking was unstoppable. Soon, Wilson wrote in 1889, all politics would be shaped by democratic institutions ‘by excluding all other governing forces and institutions but those of a wide suffrage and a democratic representation’. But even if the triumph of democracy was inevitable, according to Wilson, not all peoples would achieve it equally. ‘A people must have gone through a period of political tutelage which shall have prepared them by gradual steps of acquired privileges of self-direction for assuming the entire control of their affairs.’ They needed to demonstrate self-reliance, sobriety, and sagacity. ‘It is the heritage of races purged alike of hasty barbaric passions and of patient servility to rulers and schooled in temperate common counsel.’

Now Wilson had come to Paris to re-establish the peace, and his academic musings about democracy as the organising principle of the community of nations would become the cornerstone of the new world order. Many of the other leaders shared his view that some ‘infant’ nations needed to be led gently into the adult world of self-determination. Hence, Article 22 of the covenant of the new League of Nations distinguished between those ready for democratic self-rule and those still in need of tutelage. ‘To those colonies and territories which as a consequence of the late war have ceased to be under the sovereignty of the States which formerly governed them and which are inhabited by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world, there should be applied the principle that the well-being and development of such peoples form a sacred trust of civilization.’

It was clear which side of this dividing line Ireland wished to fall. In his tour of the United States in 1920, de Valera argued repeatedly that the Dáil had provided an unquestionable mandate to Ireland’s claim for independence, in tune with the spirit of the times: the ballot was ‘the most civilised method of delivering a national will’ and to replace it with ‘the bullet would introduce into international relations an inhuman principle of immorality’.

Maurice Walsh talks about his book, Bitter Freedom: Ireland in a Revolutionary World 1918-1923

Like Irish revolutionaries, political movements throughout the world sought to impress the leaders at the peace conference that they had the right stuff to become self-determining democracies. One of the most spectacular success stories was Czechoslovakia. They established a de facto state before the Versailles conference with a national assembly just like the Dáil. Tomas Masaryk, who styled himself as the father of the nation just as de Valera would, was installed as president. Masaryk was presented as an apostle of democracy, a great European. Like the Irish, the Czechs insisted that their nationalism was not parochial but a commitment to a reformed Europe, free from absolutist monarchies. His disciple and Czech foreign minister, Edvard Benes acknowledged their strategy in his memoirs. The Czech leadership, he wrote, had tried to make the meaning of the First World War ‘identical with that of our national revolution . . . we were successful in our struggle because we adjusted our movement to the scope of world events. We rightly joined our struggle with the struggle for universal democracy.’

The Czechs had one big advantage: unlike the Irish revolutionaries, who in 1916 had appealed to Germany in the misguided assumption that they were on the right side of history, the Czechs had supported the Allies from the beginning and were now looked on favourably by the victors. Ireland had to work harder to maintain the appearance of a sovereign state in waiting. After the Dáil was declared illegal on 11 September 1919, its members convened in private houses around Dublin. Officials of the departments of state which the assembly had established – Fisheries, Home Affairs, Local Government, Trade and Commerce – continued their work all around Dublin in offices rented under cover names.

The underground government was designed to subvert British rule; but it also projected the image of a movement capable of efficient administration. It was no coincidence that the most spectacular financial success of the counter state, the campaign to fund the Dáil by issuing ‘republican bonds’, was also the mark of a modern state. Around the same time, this was one of the first acts of the Berber guerrillas who proclaimed the Republic of the Rif in northern Morocco. After their campaign, Spanish and French colonialists established a state bank and a national currency, and spoke of ‘building the Rif into a prosperous member of the family of nations’. For post-Versailles revolutionaries, the language of success had a Wilsonian tinge.

Maurice Walsh teaches history at Goldsmiths, University of London. His book, Bitter Freedom: Ireland in a Revolutionary World 1918-1923 is published by Faber & Faber.