De Valera’s Rhetoric in the American South

By Dr Gessica Cosi

“From the Potomac to the Gulf, huge crowds have been fired with enthusiasm for the New Ireland by the stirring appeals of the soldier statesman. His audiences have not been composed, as in other parts of the country, largely of men and women intensely conscious of Irish descent. But the South can thrill to the story of the oppressed and at every stop Eamon de Valera has been made to feel that he is in a land where sympathy for him and his cause is instinctive.”

Villanova University, Digital Library. Catholica Collection. Typewritten Draft of Press Release, April 17, 1920. (Source: Digital Library@Villanova University)

Éamon de Valera’s tour to the American South in April 1920 illuminates significant aspects of de Valera’s American rhetoric and, crucially, created a precedent in the framework of Irish nationalist tours to America. As Harry Boland remarked to Michael Collins, the American South had been ‘sadly neglected’ by Irish nationalists, with the result that, by 1920, there was not ‘very much active support for the Irish movement’. Presenting the President’s itinerary, Boland crucially noted that the trip was the ‘first occasion’ on which ‘this great portion of America’ would be toured ‘on behalf of Ireland’. A point that he also made in a letter to a local organiser in Louisiana describing de Valera’s trip to the South as a ‘pioneering trip’. Except for a few isolated episodes, thus, neither Irish nor Irish American leaders had embarked on propaganda tours of the American South.

This geographical omission probably emerged in response to the small Irish population in the region, and the progressive assimilation of early immigrants into the American, and then ‘specifically’ Southern, mainstream. However, the absence of lecture tours and nationalist trips seems to be part of a broader and general phenomenon which highlights what David Gleeson has defined as a ‘gap in the historiography of Irish America’.

The tour to the Deep South was not designed to appeal to the small Irish-born American population living in the area. It was, instead, conceived as an important moment to reinforce de Valera’s broader appeal to Americans ‘at large’, while simultaneously recognising the great potential of the region in terms of political and cultural influence. His message, therefore, was not directed to the Irish regional population per se, but to the ‘American Southerns’ which incorporated, among others, descendants of both early Irish Protestant and Catholic immigrants. The interplay of these crucial dynamics was captured by the leader of the Irish in Virginia, Daniel C. O’Flaherty, who portrayed himself ‘as a Democrat, as a Virginian, a Southerner and as a Protestant’; a definition that clearly characterised the complexity of southern attitudes towards Irish affairs.

Through the tour, de Valera recognised the ‘ecumenical’ dimension of the Irish in the South and inscribed it into his broader political message. Accordingly, he recalled both Irish Catholic and Protestant experiences as co-existing parts of a regional heritage. During the trip, the President interacted continuously with both these traditions. He spoke and interplayed with prominent Protestants while simultaneously visiting numerous Catholic local institutions.

Fundamental for the development of de Valera’s inclusive rhetoric and awareness of the southern spirit were the reports elaborated by the advance agents Liam Mellows and Katherine Hughes, who had toured the area since the late 1919.

Mellows’ direct insights led the mission across the region and became crucial references for elaborating the effective oratory through which de Valera would appeal to different local communities. Generally, his historical reports recalled the legacy of local Irish men fighting for American independence and the connections between Ireland and America’s common revolutionary heritage which were pillars of de Valera’s American oratory.

To spread his message across the South – in Key’s words ‘the region with most distinctive character and tradition’ – de Valera recalled the ‘unifying’ history of the American revolution and American patriotism usually transcending North-South divisions and incorporating both Catholic and Protestant experiences.

The southern tour also represented an opportunity to strengthen Ireland’s right to nationhood in line with the principles enunciated by Wilson and as a test of ‘genuine Americanism’ in a region traditionally close to the Democratic Party and Wilson’s administration, but which lacked nationalist and community networks to spread knowledge about Ireland’s case. It was due to the widespread ‘ignorance’ on Irish affairs and the general pro-ally attitude of the area that information on Ireland had become, in de Valera’s own opinion, easy targets for British propaganda. Accordingly, it was to ‘dissipate some of the smoke clouds’ and to present the case from different angles that de Valera embarked on the mission.

The significance of the southern tour was clarified by de Valera himself when corresponding with Ireland. A few weeks before the beginning of the trip, the President recalled to Arthur Griffith how the ‘Solid South’ could influence broader national party trends towards Ireland’s case. Indirectly, he also remarked on the importance of the ‘southern campaign’ when trying to convince James O’Mara to withdraw his resignation from the mission describing the possible revocation of the tour as ‘a serious loss.’

Map of de Valera's trip to the American South. Click to enlarge

De Valera embarked on the southern tour on 8 April 1920. Starting

officially from Norfolk, Virginia, he travelled across the

Carolinas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia

for less than a month.

The itinerary was organised by the Irish mission and carried out,

in de Valera’s own words, through the

‘invaluable’ experience in the field of Mellows and

Hughes. Since the end of 1919, the latter had outlined the broader

trends affecting Irish affairs in the area. These included the

presence of strong religious and nativist bias, diffuse

pro-British sentiments and loyalty to the democratic

administration and in particular, to Wilson’s idea of the

League of Nations.

While tailoring his speeches to specific local conditions, de Valera tried to counteract these trends through a powerful idealistic rhetoric in which he generally highlighted the international dimension of the Irish question, its un-sectarian and political character, and a crucial reconsideration of the Protestant element within the broader picture of Irish and Irish American nationalism. Accordingly, as suggested by Hughes, de Valera shared platforms with Protestant speakers and prominent locals as a tactic to curb strong cultural and religious influences.

This tactic had been inaugurated during the ‘Grand Tour’ of 1919 when presenting Ireland’s political claim to nationhood across various American locations with the help of leading Protestant figures. As a result, in mid-March, Boland sent a letter to the local branches of the Friends of Irish Freedom (FOIF) anticipating the presence of Dr James A. H. Irwin, a Presbyterian Minister from Belfast, who would accompany the President throughout the region. To Katherine O’Doherty, Irwin’s presence was specifically designed to ‘nullify the statement that the Irish struggle was a religious and not a national one’, a message promoted by a delegation of six Protestant clergymen from Ulster and a member of the British Parliament, William Coote, who were touring America since the beginning of December.

Irwin’s presence in the South helped clarify the political character of the Irish question while the passage of the American Legion resolution opposing de Valera’s visit to Jacksonville, Florida, became the first concrete test for the President’s ‘inclusive’ rhetoric. It was not the first time that a post of the organisation had opposed the Irish President. In Pittsburgh, the local post had adopted a resolution condemning de Valera’s presence in America and in Portland, Oregon, there had been a major anti-de Valera demonstration by virtue of Sinn Féin’s attitude during the war. On both the occasions, de Valera had reacted highlighting the 100% Americanism of his appeal and his ‘respect’ for Americans who had died for ‘democracy’.

It was however in the South that these protests assumed the strongest connotations incorporating specific regional patterns which included, among others, the revival of anti-Catholic prejudice, the presence of a hostile and conservative mainstream, and the recurring misrepresentation of Ireland’s question as a religious case as well as a Britain’s ‘domestic’ question. The interplay of local dynamics with both domestic and international factors encouraged de Valera and the Irish mission to vigorously stress Irish American loyalty to the American government and to present Ireland’s claims in line with America’s ‘moral’ intervention in the war.

The speeches delivered in Jacksonville were tailored to cover these major arguments and to counteract local misrepresentations. Irwin underlined the political and economic aspects of the cause affirming that his presence in America showed that co-operation among Catholics and Protestants was possible. The Presbyterian Minister shared the platform with Major Michael Kelly, veteran of the 165th Infantry Regiment of New York, who had been rushed ‘to join the Chief’ in order to reject allegations of Irish disloyalty during the war. Whereas Irwin’s presence testified against the religious dimension of the question, Kelly’s rhetoric was designed to typify Irish American loyalty to the Allies where the American Legion was opposing de Valera’s visit on the grounds of alleged Irish ‘pro-German’ connections during the war.

With the religious and loyalty dimensions covered, de Valera’s message could primarily focus on the political and international aspect of the question. Remarking that Ireland was ‘no part of Britain’, it aimed at correcting that the Irish question was a ‘British domestic question’. Speaking about Ulster, de Valera recalled Irwin’s points and opposed the Ulster delegation which, he stressed, was travelling across the USA for the political ‘purpose’ to ‘smash the Irish Republican movement in America’. Whereas the Jacksonville speeches served to strengthen certain vital aspects of Ireland’s claim in America, the visit to Birmingham, Alabama, presented the opportunity to refine de Valera’s southern strategy and original rhetoric.

As put by Dave Hannigan, de Valera encountered in Birmingham the ‘most vehement resistance’ of his American campaign. The President himself described the events in Birmingham as ‘dynamite’. The opposition bonded together different segments of local cultural and political life. Led by the local Post of the American Legion, the opposition against de Valera exploded to protest against Sinn Fein’s ‘misconduct’ during the war. This was also reinforced again by the conviction that Ireland’s case was a British domestic question. Acting as a catalyst for local nativist protests, the city’s opposition represented the climax of what Francis Carroll has identified as the two main themes of anti-Irish sentiment at the time: ‘anti-Catholic sectarianism and pro-British enthusiasm as a product of the comradeship of the war’. It was in order to counteract these sentiments that de Valera strengthened his rhetoric recalling that numerous Irish citizens had volunteered in the British Army during the war for the ‘right of the small nations’.

It was not the first time that de Valera had referred to the Irish in the British Army: he had previously recalled this symbolic image in Cincinnati, Portland and in Salt Lake City where he had remarked that the Irish had fought the war ‘for a principle’. It was, however, in the South that this image assumed a profound significance: capturing multiple aspects of de Valera’s message in America, it proved Ireland’s loyalty to the principles enunciated by Wilson while effectively rejecting anti-Allies allegations. Probably thanks to de Valera’s oratory and the support of Dr Irwin and Major Kelly, the meeting in Birmingham was later recognised by the President himself as the ‘most successful meeting’.

In Atlanta, a city in which Hughes had tried to minimise

anti-Irish attitudes, de Valera confirmed that 250,000 Irish had

volunteered in the British Army for the ideals set by Wilson.

Opening his speech in Gaelic, he presented Ireland’s case as

in line with America’s war aims and appealed to the

Protestant elements in the audience pragmatically recalling the

influence of the leaders of the North on Irish republicanism.

The moral justice of the case vigorously re-emerged in Augusta on

28 April where he startled the public by openly refuting the

analogy between Ireland’s present claim and the position of

the Confederacy during the Civil War. Rejecting the analogy in the

South, where the memories of the Civil War were still an important

part of the local history, was a further step to politically

reaffirming Irish sovereignty and the international dimension of

the question.

By the end of April, having explored different places and general regional trends, de Valera’s tour of the South had almost reached its closure. In less than a month, de Valera’s speeches and appearances had been tailored for multiple audiences and locations, reflecting the different character of Irish experiences in the South. While touring the region, de Valera had faced different elements of American political and social life taking the ‘undeniable advantage’ – as a contemporary observer called it – of noticing how ‘varied’ they were. During the tour, he had conceptualised the Irish question within the American context and through specific regional, political and cultural categories. In this aspect, his rhetoric had distinguished itself from the classic messages of Irish nationalists travelling to America, consequently remarking the uniqueness and significance of his American experience.

As part of his ‘inclusive’ approach, his message had sought to transcend ‘pure’ American domestic issues in order to spread a broader, moral and international appeal that could unify varied American audiences under the umbrella of Wilsonian idealism and patriotism.

In difficult, often hostile, environments de Valera had reinforced his moral and broader appeal seeking to curb religious and loyalist prejudices commonly attributed to the cause he represented. In places like Columbia, Jacksonville, Birmingham, Atlanta, Charlotte he had adopted an inclusive strategy to commit the Protestant elements of the society towards Ireland’s case. Even in Jackson, Mississippi, where the Irish were described by a local organiser as ‘an emphatic minority’ and ‘very partisan in politics’, his address had been ‘well received’ and ‘able to correct false statements’. Fundamental for achieving such a result had been the presence of Dr Irwin and Major Kelly whose ‘patriotic assistance’ – as once explained to Boland – had strongly contributed to the Irish cause. Mary MacSwiney, remarking on the success of the inclusive strategy while travelling the area on behalf of Ireland in February 1921, would underline the importance to send ‘many’ Protestant speakers in order to ‘take advantage at once of all the enthusiasm’. The President’s success across the South also proved de Valera’s growing insight into Irish America’s varied nature and ‘regionalisms’ and inscribed, for the first time, the American South into the map of Irish America. As part of de Valera’s American legacy, in fact, even the Gaelic American – mouthpiece of Irish American classical nationalist ideology – noted in September 1920 that the South was ‘better represented’ in the national movement ‘than ever before’.

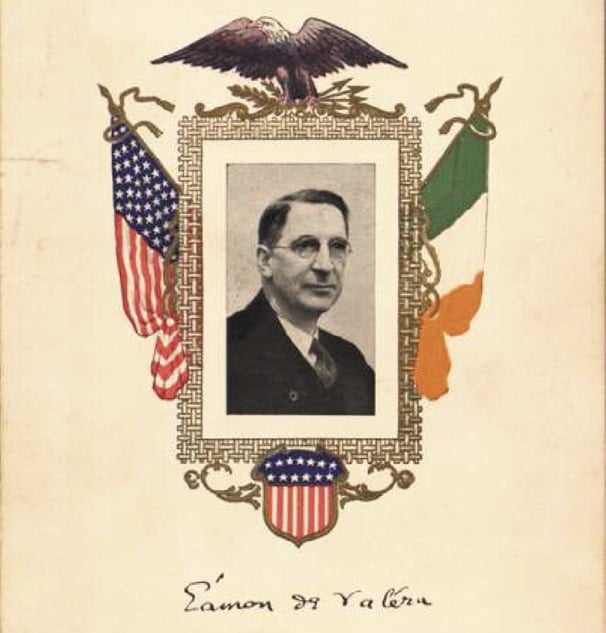

Portrait of Éamon de Valera (Image: Digital Library@Villanova University)

Dr Gessica Cosi was educated at University of Bologna and University College Dublin, where she completed a Ph.D. in History. Her doctoral thesis ‘Atlantic Connections: Éamon de Valera, the United States and Irish America, 1917-1921’ examined the interplay between Irish and Irish American identities and nationalist ideologies from 1917 to 1921 and was funded by the Government of Ireland and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs International Scholarship, and the Irish Research Council. She has taught on American, Italian and Irish American history modules in the UCD School of History and is a former Visiting Fellow of the UCD Clinton Institute where she has occasionally lectured on Irish American nationalism and politics.

Most of her research to date has involved twentieth century Irish-America and Ireland’s transnational connections with the diaspora. She is currently working on a manuscript on the historical interactions between Ireland and Irish America in the making of Irish Independence.